I recently set my freshman composition students the task of writing an essay based on each writer’s choice of a topic from a list of two hundred topics. I urged especially that writer-respondents to the assignment should strive to find interest in whatever topics they might select and that they should seek to discover the meanings in their topics. To prove that it could be done, I wrote the following essay on one topic from my own list – “Lemuria.” I append my list at the end of the essay. (TFB)

The poet and fantasist Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961) wrote of “enormous gongs of stone” and of “griffins whose angry gold, and fervid / store of sapphires [were] wrenched from mountain-plungèd mines,” which exist in a long-lost provenance, inaccessible except in dreams or by ecstatic witness. Contemplating the vision, and beseeching the reader in his opening line, the monologist of Smith’s sonnet asks the portentous question, “Rememberest thou?” Ah, remembrance! Plato’s “unforgetting”! Smith called his poem “Lemuria,” after the fabled counterpart in the Pacific Ocean of Plato’s Atlantis, the legendarily unfortunate continent, home to a high but wayward civilization, which vanished beneath the waves in a great and world-implicating catastrophe some ten thousand years ago and more. The traces of Atlantis are such geographical entities as the Canary Islands, the Azores, and the submerged Mid-Atlantic Range. Lemuria’s fragments, as enthusiasts purport, are the scattered atolls, their enigmatic monuments, as at Ponape or Easter Island, and a tissue of myth that the poetic sensibility might cherish, but that stern rationality gruffly and aggressively dismisses. Rational or not, plausible or not, the “Legend of Lost Lemuria,” like the “Story of Atlantis,” speaks to a need – or rather to a gnawing hunger – that afflicts the modern soul: To believe in the fabled, in the scientifically unsanctioned, and in the remoteness-cum-greatness of a past age that mocks the modern pretension of self-sufficiency. The allure of Lemuria, like the allure of Atlantis, responds to the vapidity and parochialism of the rational world’s priggish self-perception.

Lemuria is supposed to be as old as Atlantis (the measure of its age varies from author to author), but, as a story, it is newer than Atlantis. The story of Atlantis, the island-continent beyond the Pillars of Hercules whose people, grown decadent and greedy, attempted world-conquest only to suffer heavenly chastisement in a cataclysm that obliterated them and their homeland, goes back to Plato (428 – 347 BC). In Plato’s linked dialogues Timaeus and Critias, the Legend of the Sunken Continent figures centrally. Plato offers the Atlantis narrative as a “likely story,” whose meaning is largely symbolic and whose imagery the reader should take care not to interpret literally. Nevertheless, the tendency since Plato, especially in the Late-Nineteenth Century and again in the early Twentieth Century, was to take it literally. Lemuria only becomes a topic in the Nineteenth Century, a proposal of zoologists and ethnographers seeking to explain uniformities in the zoology of the Pacific archipelagos and in the myths and legends of their people.

According to L. Sprague de Camp (1907 – 2000), writing in Lost Continents (1948; revised 1970), the Nineteenth Century German biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) speculated in the 1880s about the “distribution of lemurs,” sub-primate creatures that appear “in Madagascar… in Africa, India, and the Malay Archipelago.” Lemurs must have originated, Haeckel thought, somewhere between these places, perhaps on a now-submerged “Indo-Madagascan Peninsula.” As de Camp reports, “The English zoologist Philip L. Sclater suggested the name ‘Lemuria’ for this land bridge.” According to de Camp, Haeckel himself “in a burst of exuberance… went on to suggest that this sunken land might be the original home of man.” Haeckel’s suggestion took fire in wilder imaginations because in the 1881 the Atlantis story had gained popularity in a book by the American Ignatius T. Donnelly (1831 – 1901), his Atlantis – the Antediluvian World. Donnelly, seeking to explain cultural similarities in the Old and New Worlds, had invoked Plato’s mid-Atlantic continent as the native ground of human civilization.

The Donnelly-theory of Atlantis soon found favor with observers curious about widespread cultural similarities in the Pacific, who transferred the reasoning of The Antediluvian World to a new environment. The occultist Helena P. Blavatsky incorporated both Atlantis and Lemuria in her encyclopedic Secret Doctrine (1888). De Camp remarks how Blavatsky’s artificial myth articulates, if rather incoherently, “a vast synthesis of Eastern and Western magic and myth about the seven planes of existence, the seven-fold cycles through which everything evolves, the seven Root races of mankind,” and other bits of baroque fantasy and delusion. In Blavatsky’s Theosophical speculation, Lemuria was the home-continent of an early “Root-Race” possessed of telepathic ability and clairvoyance, whose people corrupted themselves by experimenting in black magic and whose endeavors led to the break-up and submergence of their island. In Blavatsky’s version of history, Atlantis came after Lemuria, and represented a later stage in spiritual evolution.

Donnelly had written of Atlantis, in a far more sober tone than Blavatsky, as a place that “once existed in the Atlantic Ocean, opposite the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, a large island, which was the remnant of an Atlantic continent.” The Antediluvian World argued that Atlantis was “the region where man first rose from a state of barbarism to civilization,” and that when it sank, “a few persons escaped in ships and on rafts, and carried [with them] to the nations east and west the tidings of the appalling catastrophe, which has survived to our own time in the Flood and Deluge legends of the different nations of the old and new worlds.” James Churchward (1851 – 1936), less sober than Donnelly but less fantastic than Blavatsky, wrote copiously about Lemuria, which he called “Mu,” in the 1920s and 30s. Among Churchward’s titles are: The Children of Mu (1931), The Lost Continent of Mu – Motherland of Mankind (1931), and Cosmic Forces of Mu (1934). As Donnelly argued about Atlantis, so Churchward argued about “Mu”: It was the Ur-Civilization, a high Bronze-Age society, which ended in catastrophe and in the Diaspora of its survivors. In The Lost Continent, Churchward wrote: “The civilizations of India, Babylonia, Persia, Egypt and Yucatan were but the dying embers of this great past civilization.”

The context of these seemingly outrageous claims should be taken in consideration. The second half of the Nineteenth Century saw remarkable discoveries in archeology. Fabled places long thought to be purely legendary or fantastic exposed themselves to the digger’s spade. Most famously at the hill called Hissarlik in Northwestern Turkey, Heinrich Schliemann (1822 – 1890) in 1876 revealed the existence of a late-Bronze-Age city that he identified (and whose identification has long been certified) as the Troy of Homer’s epic poems The Iliad and The Odyssey. Sir Arthur Evans (1851 – 1941) excavated the fabled Palace of King Minos at Knossos in Crete between 1900 and 1903. These and other events seemed, to many people, to confirm the reality of legend and folklore; at the same time, and by extension, they called into question the standing version of history. To discover Troy or Knossos was to pluck at many a stuck-up beard – a rare pleasure ardently sought after by a gadfly type of person. To validate Atlantis or Lemuria would be even better yet.

Central to any discussion of Lemuria as a pseudo-archeological fact is the authorship of the Scotsman, and Scots nationalist, Lewis Spence (1874 – 1955), better-known as a folklorist, an advocate of the case for Atlantis, but also, in two books, an exponent of the reality of the lost continent of the Pacific. In The Problem of Lemuria: The Sunken Continent of the Pacific (1932), Spence wrote of his surprise, on collating the evidence, that “the myth of Lemuria in its Polynesian form, and the Myth of Atlantis as told by Plato, have a common basis.” Spence wrote indeed of an “Atlantis culture-complex” that he had detected in archeology and myth, “from Spain to the Sandwich Island,” that is to say, Hawaii. The Problem of Lemuria, like the same author’s Problem of Atlantis (1924), marshals abundant geological, archeological, and mythological evidence to support the claim that the existing islands and cultures of the Pacific stem from a geologically and culturally unified, and very ancient, mid-oceanic landmass.

Some of Spence’s chapter-titles are: “Arguments from Archeology”; “The Testimony of Tradition”; “Evidence from Myth and Magic”; and “The Geology of Lemuria.” In the chapter on “The Catastrophe and its results,” Spence paints a tragic and awesome picture of a doomed people scrambling to save their society as the quite un-metaphorical ground-under-their-feet slips away into the salty abyss. Spence also paints the moral picture of a society that had fallen into the corruptions of avarice, arbitrary class-divisions, and various forms of practical wickedness, which undoubtedly exacerbated the natural catastrophe and perhaps even precipitated it. “That wholesale destruction of life occurred in certain areas we cannot doubt, having regard to the quite recent geological history of Japan, where earthquake has accounted for hundreds of square miles, and horrified beholders on vessels at sea have witnessed the collapse and engulfment into ocean of entire countrysides with their houses, farms, animals and populations complete.”

Here Spence in his own words reminds readers of another aspect of the allure of Lemuria, as well as of Atlantis, for both are stories of inescapable destruction that urge from the audience the emotions of pity and fear.

As for the moral contribution of the Lemurians to their own misfortune, Spence contents himself with citing myth, not bothering to dismiss it: “Man must not arrogate to himself the joys of heaven, or imitate its hauteurs” because “human profligacy [has] a direct and blighting effect on the powers and economy of nature.” If so-called primitive people believed that “the wholesale destruction of nations or countries” followed from the indignity of an “outraged deity,” who among modern people, the people who had murdered one another in the trenches in “The War to End War,” could sincerely gainsay the old idea? Indeed, a later book by Spence from 1943 bears the title Will Europe Follow Atlantis? The answer to the titular questions is, probably yes, but if not, then Europe bloody well ought to follow Atlantis, and the sooner the better.

De Camp writes that “Spence’s facts… turn out less impressive than they seem at first,” and dismisses him for “consider[ing] legends more reliable evidence of past changes in the earth’s surface than geology, despite the fact that to change a story he has heard is one of the easiest things for a man to do, while the rocks stay much the same from age to age.” Even conceding that Spence began sanely, de Camp argues, “his own critical sense seems to have declined with the years.” De Camp is especially vicariously embarrassed by Spence’s Will Europe Follow Atlantis? Martin Gardner (1914 – 2010) too in Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1952) believes that while Spence began as “one of the sanest” lost-continent advocates, he later “became obsessed with what he thought was a parallel between the decadence of ancient Atlantis [and, of course, Lemuria] and the decadence of modern Europe.” In sum, as Gardner sees it, Spence was one more crank and Lemuria is nothing but crankiness.

Despite so much skepticism, the idea of Lemuria as a fact persists. Frank Joseph, writing in The Lost Civilization of Lemuria – the Rise and Fall of the World’s Oldest Culture (2006), insists that “Lemuria undoubtedly did exist in the past… [and] was the birthplace of [the earliest] civilized humans” whose “mystical principles survived to influence fundamentally some of the world’s major religions.” Frank’s Afterword, “The Real Meaning of Lemuria,” begins with an epigraph from Spence on the decline of the lost continent (whether it be Atlantis or Lemuria) into decadence and unto “utter barbarism”; and it ends with the declaration that “although her broken remains have lain at the bottom of the sea for the last twenty-three centuries, the Motherland’s spirit is alive in the folk memories and high spirituality of more than a dozen different peoples around the Pacific Rim.” Frank concludes summarily: “In this age where the unnatural is normal, nothing is too good for self-indulgence, and the Earth is pushed to the brink of ecological revolt, we need a different role model from our past.”

Frank, in 2006, calls for a “Return to Lemuria,” a phrase that attests the “allure” invoked in these paragraphs from the beginning. Prior voices anticipated Frank’s call by decades. Clark Ashton Smith, already mentioned, wrote at least a dozen “Lemurian” stories for his usual venue, Weird Tales, in the 1930s, only Smith renamed the foundered Pacific continent “Zothique” (as in the French, exotique). Smith, a correspondent and follower of H. P. Lovecraft, felt attracted to the Lemuria-myth because of the aura of decadence that hovered over it, but he relocated his disintegrating insula oceanica from humanity’s dim past to its gray doom in the twilight of the far future. Smith’s Lemurian stories – “The Empire of the Necromancers” (1932), “The Isle of the Torturers” (1933), “Necromancy in Naat” (1933), and “Xeethra” (1934) – depict the Lemurian decadence, as described by Spence and Scott-Elliot, but in the mode of the baroque fable and under the philosophical premises of the French Symbolist poet Charles Baudelaire’s verse-collection The Flowers of Evil (1857). The narrator of “The Empire” begins this way: “I tell the tale as men shall tell it in Zothique, the last continent, beneath a dim sun and sad heavens where the stars come out in terrible brightness before eventide.”

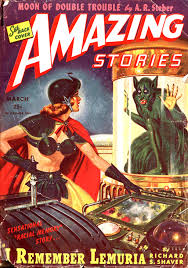

Beginning in the March 1945 number of the science fiction pulp magazine Amazing Stories, during the editorship of Raymond Palmer, items began to appear by one Richard Shaver (1907 – 1975) that Palmer declared in his editorial comments to be other than fiction. Shaver, an out-of-work welder who had been institutionalized in a psychiatric hospital, had experienced voices and out-of-body trances that convinced him, as the title of his best-known story phrased it, that I Remember Lemuria. Shaver’s stories of his past life in Lemuria, of the catastrophe that overwhelmed the Lemurian civilization, and of the subterranean survivors of that catastrophe, both benevolent and malevolent, dramatically increased the sales of Amazing until the appearance of the final installment of “The Shaver Mystery” in 1949. In Shaver’s stories, the Lemurian civilization is space-traveling and interplanetary; in this way the old myth absorbs the elements of science fiction.

Shaver’s stories link up with a putatively non-fiction book about Lemuria, W. S. Cervé’s Lemuria – Lost Continent of the Pacific (1931), which argues that a Lemurian colony persists in caverns under Mt. Shasta in Northern California. Even Santa Barbara, according to Cervé, is a remnant of Lemuria. Nerds over fifty who read science fiction in their youth might remember the “Thongor” stories of Lin Carter (1930 – 1988), prolific paperback-writer of genre fiction: The Wizard of Lemuria (1965), Thongor of Lemuria (1966), Thongor against the Gods (1967), Thongor in the City of Magicians (1968), Thongor at the End of Time (1968), and Thongor and the Pirates of Tarakus (1970). Carter writes, “Where now the Blue Pacific rolls a thousand miles without a break… there was once, in the dawn of the world, a mighty continent, thronged with glittering cities of marble and gold.” Each paperback installment of the series included a map of Lemuria, drawn by the author.

Science tells us that the world is stable, that progress is steady and assured, and that the present is the summit of humanity’s aspirations. The allure of Lemuria is to doubt all that.

![Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World by [Laura Spinney]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/519h4vTGQDL.jpg)