Exposing the Invisible Empire

AFTER A WHITE SUPREMACIST gunned down nine black worshippers at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, last June, reporters at The Post and Courier, where I work, filed hundreds of stories on the shooting and its aftermath. One of my pieces, about questionable financial dealings by the church’s interim pastor, elicited a threatening email. As I scanned it on my laptop at home, one line chilled me: “If you’re reading this tomorrow morning it’s probably too late.”

My kitchen table sits next to a bay window that overlooks a wooded easement. It has no curtains. I’d never needed any here in Charleston, a famously charming city that is home to some of the country’s best restaurants and most beautiful people, according to organizations that rate those sorts of things. But now the darkness beyond felt ominous. I stepped away from the window and called my editors.

I was reminded of that moment recently as I read about W. Horace Carter, the 29-year-old founder of the Tabor City Tribune, who watched a line of cars cruise down the main drag of his North Carolina town one hot July night in 1950. His newspaper covered a border area with South Carolina, and back in Carter’s day, Jim Crow notions of segregation ran especially thick and deep in both states. The motorcade carried 100 white-robed, hooded, armed men who tossed out pamphlets before rumbling down a dirt road toward the town’s black community.

Carter bent to pick up a leaflet. “Beware of association with the niggers, Jews and Catholics in this community,” it read. “God didn’t mean for all men to be equal.”

Four days later, the native North Carolinian published “An Editorial: No Excuse for KKK.” It was the first of many in which Carter challenged the Klan’s habit of meting out vigilante justice to whomever they thought deserved it, sans judge or jury. “In every sense of the word, they are endeavoring to force their domination upon those whom they consider worthy of punishment,” Carter wrote. “It is not for a band of hoodlums to decide whether you or I need chastising.”

A fearless and wiry war veteran who had nearly become a Christian missionary, Carter also publicly doubted that KKK members who espoused religious orthodoxy to justify their violence actually practiced the faith they preached. “If you had church attendance slips for those persons, it’s our opinion that not five percent of them entered any church of any denomination on Sunday morning,” Carter wrote.

Willard Cole, a newspaper editor in Lumberton, North Carolina, types at his desk. Cole, who won a Pulitzer for his crusade against the KKK, could only type with his right arm after a stroke in 1961, so he made alterations to his typewriter so he could type one-handed, 1964. (Associated Press )

He and his family awoke the morning after tha first editorial was published to a threatening note stuck under one of Carter’s windshield wipers. Two more waited under the door to his newspaper office, says Utah State University journalism professor Thomas C. Terry, who has researched Carter for more than a decade.

Soon after, a larger Klan motorcade hit Myrtle Beach and Atlantic Beach. This time, its members shot at a popular black nightclub and savagely beat its owner. And as Carter’s newspaper wrote more than 100 editorials and stories over the next three years, the local grand dragon visited twice to warn him that the KKK would put his newspaper out of business. He received more than 1,000 death threats. His dog was kidnapped. His 4-year-old son asked: “The Klan gonna come and get you, Daddy?”

They didn’t. Instead, the words of Carter and a friend and colleague named Willard Cole, editor of the much larger Whiteville News Reporter nearby, prompted action. In 1952, the FBI arrested 10 KKK members, triggering a tide of other arrests. Eventually, almost 100 Klansmen were tried and convicted. The two newspapers shared the public service Pulitzer in 1953 for their campaign, “waged on their own doorstep at the risk of economic loss and personal danger.”

“He acknowledged being scared, especially for his family,” Carter’s son Russell later told The New York Times. “But he was a newspaperman.”

These days, we tend to think that even those who tackle the most sensitive public service journalism in the US are mostly safe from physical harm. That isn’t always the case, but the author of the threatening email I got last year surely hadn’t infiltrated my local police department. He probably didn’t live next door, or run businesses I frequent. I doubt he worked for the mayor or city council. The challenges journalists face exposing race and hate crimes today generally—though not always—pale beside the ongoing terror editors like Carter and those before him felt while challenging the KKK, whose insidious tendrils reached far deeper into the communities where they lived than hate groups do today.

Despite those risks, a spate of Jim Crow-era newspaper campaigns exposed racists like accused Emanuel AME shooter Dylann Storm Roof, albeit shrouded in white hoods back then. Their coverage of racial injustice also shaped and molded the public service Prize, the most revered journalism award today.

The pattern of awarding Pulitzers for Klan coverage began almost immediately after the gold medal’s birth in 1918. Several exposés and editorials challenging the KKK won Pulitzers throughout the 1920s, when the secretive group enjoyed a revival, and again in the 1950s, when the seeds of the Civil Rights movement rooted in the South.

That winning journalism, with its enormous risks and impact, embodied what Joseph Pulitzer intended to celebrate when he created the awards, and what his awards have come to honor a century later: courage, persistence, empowering the powerless. It also had a lasting impact on race relations in America, as individual journalists like Carter risked the fury of their communities to fight for change.

JOSEPH PULITZER ADVOCATED for quality newspapers. However, his name once was most closely associated with the yellow journalism of the 1890s, spouted from his own New York World in an effort to trump fellow New York newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst.

A key motivation for creating his Pulitzer Prizes? “To put that era behind him,” says Roy J. Harris Jr., who has chronicled all 100 years of the public service awards in his book Pulitzer’s Gold: A Century of Public Service Journalism.

Shortly before creating the Prizes, Pulitzer crafted a platform that still could guide the best J-schools and newsrooms. It’s a lot to jam onto a conference room whiteboard today, but Pulitzer declared his newspapers would “never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, never belong to any party, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfied with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty.”

Carter received more than 1,000 death threats. His dog was kidnapped. His 4-year-old son asked: “The Klan gonna come and get you, Daddy?” They didn’t.

During his last decade of life, Pulitzer came up with an idea that would push these ideals of public service beyond his own newsrooms. He planned a series of prizes aimed at elevating journalism to one of the great intellectual professions, a status it didn’t enjoy at the time. As the notion gelled, he decided to bequeath $500,000 to Columbia University for the Prizes as part of his $2 million endowment to fund a journalism program at the school.

Pulitzer died in 1911, and six years later, his Prizes were born. No public service Prize was given in 1917, the Pulitzers’ inaugural year. Instead, the gold made its debut the following year, when The New York Times won for its coverage of World War I.

But what exactly did “public service” mean back then? Newspaper journalists didn’t have much to go on, says Harris. “There really had not been a model for this in 1917 when they were first handed out.” That quickly changed.

THE FIRST MAJOR EXPOSÉ outing the Invisible Empire, as the KKK was known, sprang from the pages of Pulitzer’s own New York World, then an industry powerhouse whose staff worked out of the planet’s tallest building. Pulitzer felt strongly that journalists had a duty to victims and underdogs, “and clearly that would apply in the case of blacks being tortured and lynched,” Harris says.

Beginning on Sept. 6, 1921, the World’s newsroom embarked on a 21-day series that revealed the inner workings of the hate group, which had been enjoying a largely unencumbered resurgence. Klansmen had revived their ranks during World War I using new recruitment tactics—like adding Jews and Catholics to their targets—and attracted hundreds of thousands of new members. They infiltrated state and local governments across the country and set their sights on other powerful institutions, including the Army and Navy.

After a three-month investigation, the World’s reporters did what good reporters routinely do today: They challenged the hate group and gave a voice to its victims.

The first story appeared with an all-caps, 1A headline whose size might make today’s copy editors cringe: “SECRETS OF THE KU KLUX KLAN EXPOSED BY THE WORLD; MENACE OF THIS GROWING LAW-DEFYING ORGANIZATION PROVED BY ITS RITUAL AND THE RECORD OF ITS ACTIVITIES.”

A front-page photo showed two men standing in the woods shaking hands in front of a cross and an American flag. One wore the KKK’s telltale white robe, mask, and pointy hood. The other man’s face wasn’t covered, and the caption named him: Col. William Joseph Simmons, emperor of the Invisible Empire, though after this series it wouldn’t be invisible any longer.

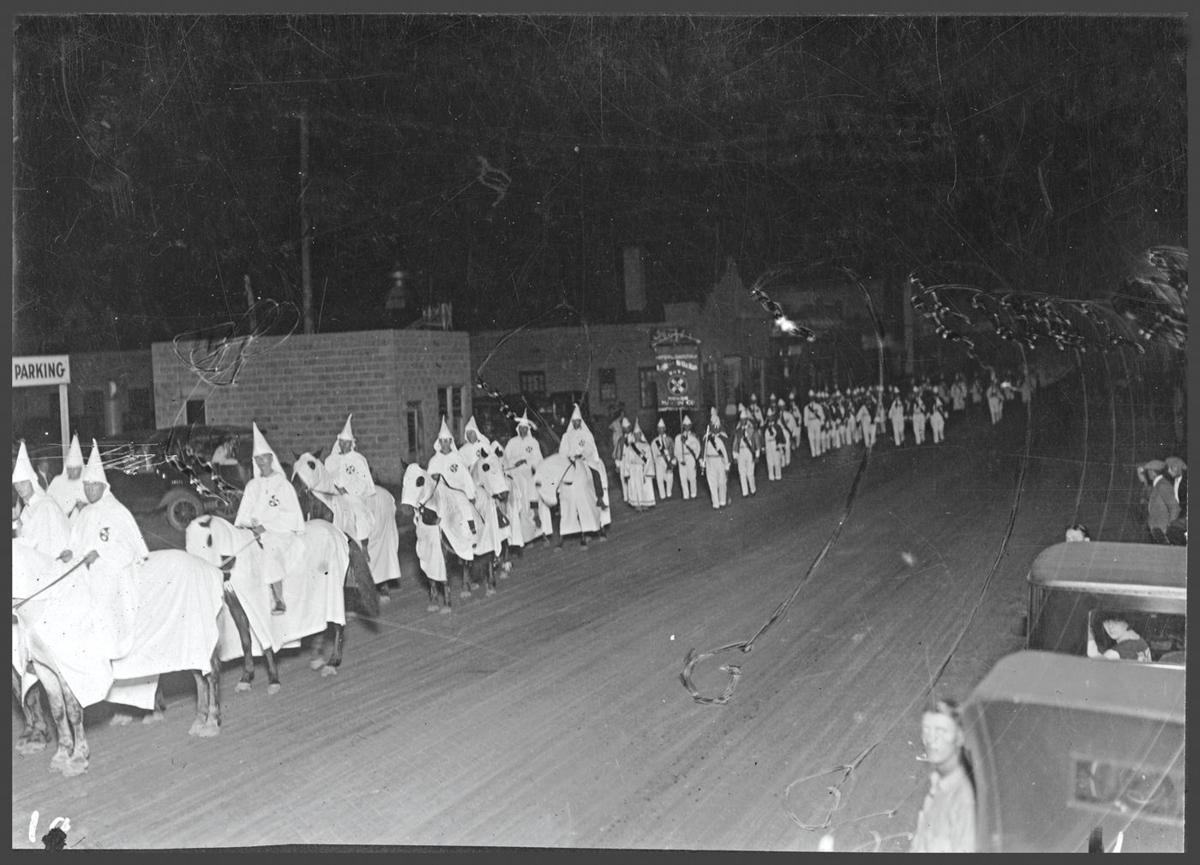

Hooded members of the KKK meet for a demonstration in Baltimore, Maryland, 1923. (Transcendental Graphics / Getty Images)

After months of investigation, “in the performance of what it sincerely believes to be a public service,” the newspaper promised to dig deep into “as extraordinary a movement as is to be found in recent history,” the opening story avowed.

Tapping documents and insider sources, including dozens of former KKK members, the World exposed everything from the Klan’s money-making schemes to its secret oaths and terrifying violence, including floggings and tar-and-feather terrorism. “Oath-bound secrecy, bolstered with the trumpery device of a ghostly sheet and pillow slip regalia, is the very lifeblood of Ku Klux, Inc.,” one story said.

When the predictable threats arrived, the World responded by reprinting letters that called its journalists “nigger lovers,” and one that warned: “You will have the pleasure to receive the necessary punishment for the publication of your series of articles regarding the secrets of our powerful and holy order.”

Eighteen other newspapers nationwide ran the World’s series, including such titans as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, The Boston Globe, the Times-Picayune, the Houston Chronicle, and The Milwaukee Journal. The series drew two million readers nationwide. New Yorkers stood in line for copies. And the Justice Department and several congressmen promised to investigate the group, all reactions journalists hope to see today from our own work.

The World won the public service Prize in 1922, the fourth year it was given. At the time, the Prize “for the most disinterested and meritorious public service rendered” came with a gold medal worth $500.

IN THE EARLY 1920S, the Pulitzer Prizes weren’t the top-dog awards they are today. After Pulitzer died, his two sons’ longtime service on the board ensured their father’s principles would guide the Prizes—and in turn, American journalism. But they faced an arguably self-imposed hurdle to attracting top journalists: Pulitzer’s own papers fared quite well, perhaps too well, in the early competitions. During the 1920s, the Pulitzer-owned World won the public service Prize alone three times.

“The board members—and especially the Pulitzer brothers—certainly had not intended for the Prizes to favor the Pulitzer newspapers,” Harris writes in Pulitzer’s Gold. But perceived favoritism threatened their goals. So, the brothers withheld entries from their newspapers in 1930, 1931, and perhaps other years as well, Harris says.

Still, the long-term impact of those early Prizes remains clear.

“For all the perceived questions about favoritism, the Public Service Prize had at least been defined in the 1920s,” Harris writes. The Prizes demonstrated the critical need for courageous coverage, giving voice to victims, and a willingness to take on those in power. Pulitzer board members “knew that racial hatred was a national scourge of the kind Joseph Pulitzer hated.” They wanted to keep the issue prominent.

The fight against the KKK didn’t stop—couldn’t stop—in New York. The mantle was passed to local journalists in KKK-laden states who would suffer the brunt of retaliation for taking on Klan members, some of whom held high posts in their communities, and had deep advertising pockets.

The next major anti-KKK campaign was launched from the southern city of Memphis, where Klan recruiters had arrived in 1921 and quickly boasted 10,000 members. A year after the World’s series won the Pulitzer, The Commercial Appeal launched a two-pronged attack against the hooded order’s alarming local influence.

The KKK had expanded beyond promoting racial and religious hatred. It had become a sort of moral police force that . . . doled out violent punishments as its members saw fit.

By then, the KKK had expanded beyond promoting racial and religious hatred. It had become a sort of moral police force that singled out alleged drunks, adulterers, bootleggers, and the like, and doled out violent punishments as its members saw fit. The Commercial Appeal’s 1923 crusade was as much a battle against the Klan’s attempt to mete out vigilante justice and control local elections as an effort to support racial equality.

Indeed, the newspaper hadn’t always been known as a crusader for the fair treatment of black residents. Just six years earlier it had published the scheduled lynching time of Ell Persons, a black man accused of raping and killing a white teenager. Thousands of people turned out to watch a man who hadn’t been convicted be burned alive and dismembered.

But now, the newspaper’s editor, C.P.J. Mooney, condemned the Invisible Empire, dubbing it a money-making scam that was terrorizing residents. He took particular offense to Klansmen meting out their own version of religious and criminal justice.

“The law is the soul of the nation,” Mooney wrote, arguing the group had no right to assume the role of the police and court system.

His newsroom didn’t rely on words alone. Cartoonist J.P. Alley crafted searing front-page depictions that ridiculed the KKK as cowards behind bed sheets. One portrayed a man lashing a woman across her back and proclaimed: “His ‘noble work,’ done in the dark!” When KKK members sent Alley threats, he used them as fodder for more cartoons.

The newspaper’s drubbing of the Klan escalated until it became central to the 1923 municipal elections. After the city’s mayor refused to join the KKK, the hooded order supported opposing candidates for mayor and city commission. In an effort to intimidate its journalistic opponents, Klansmen set up their campaign headquarters right across the street from the newspaper’s building and invited national KKK leaders to visit, American University journalism professor Rodger Streitmatter writes in Defying the Ku Klux Klan.

The Commercial Appeal hammered on. Tension built to Election Day. As voting ended, 400 Klan members demanded the ballots be counted in public.

They were defeated easily. When the mayor paraded triumphantly through town, he stopped at the newspaper building “and directed the band to serenade the newspaper in honor of its decisive role in the election,” Streitmatter writes.

The year after the World won for its KKK coverage, the Memphis paper won “for its courageous attitude in the publication of cartoons and the handling of news in reference to the operations of the Ku Klux Klan.”

THE JOURNALISTIC BATTLE soon spread to other cities in the South where Klansmen freely roamed halls of power. In 1925, two years after The Commercial Appeal’s Pulitzer win, the brutal murder of a mentally ill black man sent an irate Georgia newspaper owner to hammer on his typewriter. Julian LaRose Harris, a WWI veteran and son of writer Joel Chandler Harris (of African-American folklore’s Uncle Remus fame), had purchased a controlling interest in the Enquirer-Sun and become its general manager.

When he moved to town, the local Klan met on the second floor of the police station “with the tacit support of city officials,” Gregory C. Lisby wrote in his 1988 article, “Julian Harris and the Columbus Enquirer-Sun: The Consequences of Winning the Pulitzer Prize,” published in the industry journal Journalism Monographs.

On Sept. 24, 1925, the front page headline in the Enquirer-Sun read: “Lynching a Lunatic the Latest Infamy Added to Georgia’s Long List of Disgraces.”

“The human mind cannot conceive of a crime more malicious, more despicable, or more inhuman than that of the cruel and cowardly group of Georgians who lynched this negro lunatic—a poor, mindless creature who, before the law, stood on the same plane with an infant!” the story declared. It went on to describe how the mob “beat the miserable lunatic’s head to a jelly with the pick-axe handle which he used in his insanity to strike down his victim.”

An FBI agent drives along a North Carolina road during an investigation into KKK members, who were accused of abducting and flogging residents, both Caucasian and African American, 1952. (Robert W. Kelley / Getty Images)

It wasn’t what most readers in the state where the KKK launched its resurgence expected to read in their hometown Bible Belt paper—not that they didn’t have warning. Harris had been one of the few southern newspaper editors to run the World’s initial series exposing the Klan. He had wanted to print it so badly he’d begged to use the content for free because he couldn’t afford to pay for it. Although he was born in Savannah, Harris was a progressive who ran a box in his newspaper promising that it “seeks to reflect the best thought and sentiment of the public but will not cater to passing public opinion.”

On Dec. 31, 1925, to wrap up the year, Harris asked on his front page: “Is it great to be a Georgian?” The article condemned those who supported “a cowardly hooded order,” including the state’s governor and other officials.

The consequences for Harris and his newspaper were swift. The Enquirer-Sun’s machinery was vandalized. It lost 20 percent of its circulation—about 1,000 subscribers—after KKK members demanded a boycott, Lisby wrote.

Yet Harris never changed his four-block path home at night. And a few fellow southern newspapers supported him. Alabama’s Montgomery Advertiser called Harris “one of the two or three most useful Georgians living.”

The Pulitzer Board agreed. His newspaper won the 1926 gold medal for “its brave and energetic fight against the Ku Klux Klan.” It was only the second southern newspaper—and the first small daily—to win the prize. H.L. Mencken called it “the most intelligent award the committee has yet made.”

Sadly, national accolades didn’t pay Harris’ bills. In 1929, he sold the newspaper and, saddled with debt, left the city.

But Harris didn’t leave his ideals behind in his newsroom. He joined the Pulitzer Prize Advisory Board and later The New York Times staff.

Several years later, in 1928, the Indianapolis Times also received the public service Prize for an anti-corruption crusade that exposed public officials, including the state’s governor and former treasurer, for their KKK ties. “Both the governor and former treasurer were indicted, in part because of what the Times wrote,” Pulitzer Prize historian Roy Harris says.

It was the fourth gold medal awarded for Klan coverage in the 1920s alone, and this time, the Pulitzer Board overruled jurors who had recommended awarding the Prize to a campaign to improve farming methods.

THE PULITZER BOARD’S SELECTION of so many anti-Klan crusades set a bar for public service journalism, which was now expected to battle injustice and uphold the rights of its victims, regardless of risk.

“Recognizing the importance of these stories so early on in the ’20s into the ’50s was truly remarkable,” Pulitzer historian Harris says. “You always had the Pulitzer family looking out for their benefactor’s original plan and his philosophy. The Pulitzer Prizes helped guide journalism in the direction of public service.”

Had newspapers not exposed the Invisible Empire early in the 20th century, KKK ranks might be considerably more robust than they are today. Editors like Carter in the Carolinas changed their hometowns. “He drove the Klan out, the FBI came in, and the largest mass trial in North Carolina history was held,” says Terry, the Utah State University journalism professor. “He was a leader in it, a pioneer.”

The Klan remains a stubborn threat. 892 hate groups were active in 2015, up from 784 the previous year. Boosts among KKK sects fueled that surge. They numbered 190, up from 72 in 2014.

Yet even today, with the 100th Pulitzer Prizes just awarded, racial hatred persists.

Look no further than Emanuel AME Church. Accused killer Dylann Roof didn’t belong to an organized hate group like the Klan. Police have dubbed him a “lone wolf” killer, today’s more alarming threats because they form hate-filled ideologies by reading online rants rather than joining organized groups that can be tracked and monitored.

The Klan, too, remains a stubborn threat. In recent months, the Southern Poverty Law Center released its latest analysis of hate groups and found 892 were active in 2015, up from 784 the previous year. Boosts among KKK sects fueled that surge. They numbered 190, up from 72 in 2014.

Klan ranks grew after South Carolina lawmakers removed the Confederate battle flag from their statehouse grounds last summer in response to the Emanuel church shooting. Klan and like-minded groups then held at least 364 pro-Confederate flag rallies in 26 states and Washington, DC, last year, the Southern Poverty Law Center report says.

That might not be as alarming as it sounds. One of those rallies, held at the South Carolina Statehouse last July, drew about 50 members of the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Tempers predictably flared when counter-protesters arrived. Yet the worst threat that day turned out to be the suffocating midsummer heat, and one of the most memorable moments came not from violence, but from a gesture of human kindness captured in a news photo.

It shows South Carolina’s black director of public safety, clad in his police uniform, gently helping a wrinkled and frail neo-Nazi suffering from heat exhaustion into an air-conditioned building.

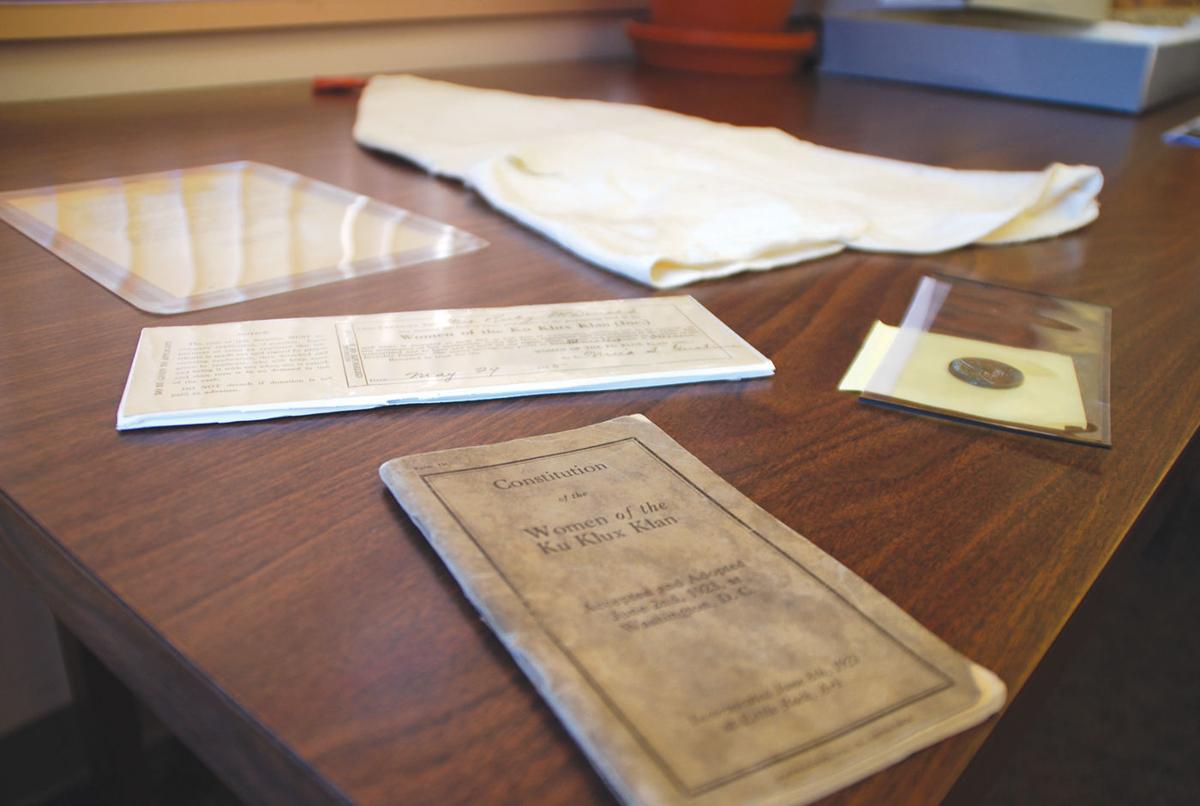

![KKK book [Duplicate]](https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/mankatofreepress.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/2/63/26308be6-8a29-51ee-a428-ec77a94b0f1b/54059780a349a.image.jpg)