The First Transcontinental Railroad changed America forever, but thousands of men who had toiled on the tracks were erased from history

On the 150th anniversary of its inauguration, hundreds of Chinese-Americans gather in Utah to set the record straight

Alan Chin 23 May, 2019

New York photographer and activist Corky Lee’s 2019 reenactment of the iconic 1869 photograph, but with the descendants of Chinese railroad workers and other Chinese-Americans. Photo: Alan Chin

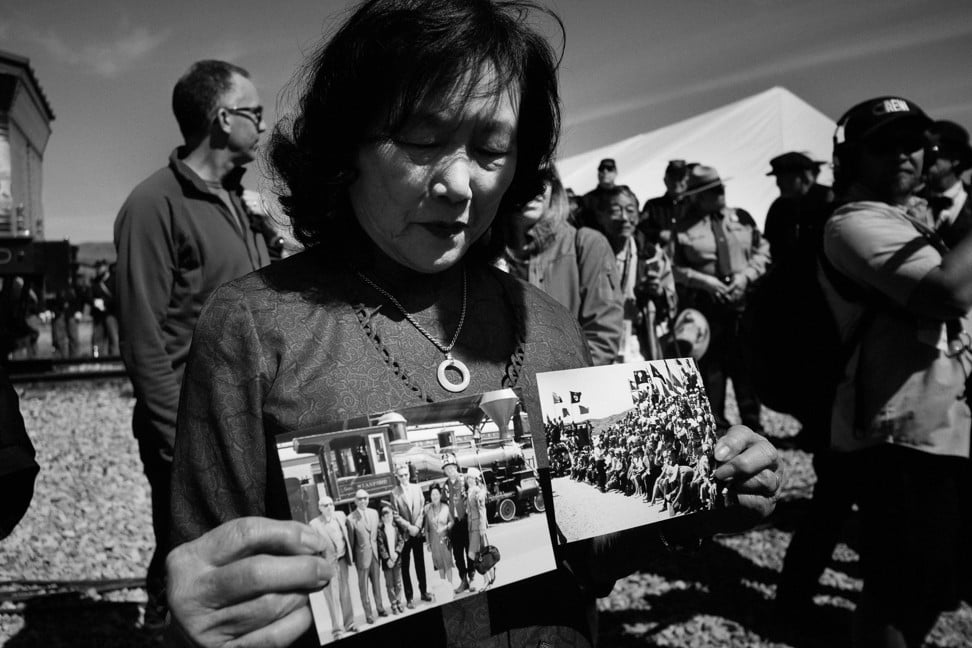

Connie Young Yu has put forward her arguments many times. Having been invited by the United States’ National Park Service to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the inauguration of the First Transcontinental Railroad, the writer and historian stands on stage in Promontory Summit, Utah, before 20,000 people, and opens the commemorations: “My great-grandfather, Lee Wong Sang, was one of the thousands of unsung heroes, building the railroad across the Sierra Nevada mountains, laying tracks through to Utah, uniting the country by rail.

“Many descendants of Chinese railroad workers are here today. This is a far cry from 50 years ago. [Then], my mother, Mary Lee Young, was the only such descendant present. Yet why were the Chinese denied their rightful place in history at the 100th anniversary?” Yu asks.

“Why was Philip Choy, president of the Chinese Historical Society of America, kept from making a presentation on the official programme?”

Choy, who was also an architect, was in attendance at the 1969 ceremony but was denied the five-minute address to the audience he had been promised, in which he planned to acknowledge the contribution made by Chinese labourers. It is said that his slot was instead given to actor John Wayne.

“Because the contribution of the Chinese to the Transcontinental was kept from national memory,” Yu says, answering her own question. “The Exclusion law of 1882 stopped the immigration of Chinese labourers, and denied all Chinese naturalisation to US citizenship.”

The iconic photograph taken by Andrew J. Russell on May 10, 1869, in Promontory Summit, Utah, after Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California, ceremonially drove in the railway line’s golden Last Spike. Despite as many as 15,000 Chinese having worked on the railroad, none are pictured. Photo: Andrew J. Russell

The Chinese Exclusion Act was followed, in 1892, by the Geary Act, which was still more draconian and demonstrated the lengths to which authorities would go to expunge Chinese people from the American experience. Not only were no more Chinese labourers allowed to immigrate to the US, those already in the country were told they had to carry at all times a resident’s permit.

Failure to do so (and few did) was punishable by deportation or a year’s hard labour. “In effect, for 61 years, the law excluded the Chinese from American history.”

Failure to do so (and few did) was punishable by deportation or a year’s hard labour. “In effect, for 61 years, the law excluded the Chinese from American history.”

Standing a few feet away, listening to her remarks boom from loudspeakers, caressed by a cool breeze, tears well up in my eyes and a chill runs down my spine. As a Chinese-American, I trace my own lineage to a village not a dozen miles from that of Yu’s great-grandfather, in Toishan county, Guangdong province.

Although my ancestors didn’t work on the American railroad, they too embarked on extraordinary parallel journeys to arrive on the New World’s shores: smuggled in the coal holds of steamships, assuming fictional identities as paper sons and suffering decades of separation from wives and children.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on May 10, 1869, the First Transcontinental Railroad – a 3,077km (1,912 mile) line connecting America’s eastern rail network with the Pacific coast, on San Francisco Bay – was completed.

The rail link would revolutionise settlement of the American West as well as its economy; it would bring the western states and territories into alignment with the northern industrial states and make the transport of passengers and goods from coast to coast quicker and less expensive.

Corky Lee at the Chinese Arch, a natural formation marking the spot where Chinese railroad workers camped in 1869. Photo: Alan Chin

Through traffic began to roll after Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California (and founder of Stanford University), drove in the Last Spike.

Made of gold – it would later be referred to as the Golden Spike – it was driven home with a silver hammer here, at Promontory Summit, a desolate spot on the high plains in what was then not yet a state.

The steam locomotive, the telegraph and the photograph were among the most important developments of the 19th century, and all three played their part in this historic moment. News of the railroad’s completion was disseminated from the site by telegram once Stanford had struck the Golden Spike.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on May 10, 1869, the First Transcontinental Railroad – a 3,077km (1,912 mile) line connecting America’s eastern rail network with the Pacific coast, on San Francisco Bay – was completed.

The rail link would revolutionise settlement of the American West as well as its economy; it would bring the western states and territories into alignment with the northern industrial states and make the transport of passengers and goods from coast to coast quicker and less expensive.

Corky Lee at the Chinese Arch, a natural formation marking the spot where Chinese railroad workers camped in 1869. Photo: Alan Chin

Through traffic began to roll after Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California (and founder of Stanford University), drove in the Last Spike.

Made of gold – it would later be referred to as the Golden Spike – it was driven home with a silver hammer here, at Promontory Summit, a desolate spot on the high plains in what was then not yet a state.

The steam locomotive, the telegraph and the photograph were among the most important developments of the 19th century, and all three played their part in this historic moment. News of the railroad’s completion was disseminated from the site by telegram once Stanford had struck the Golden Spike.

‘Go back to where you came from’: author on plight of Asian refugees

15 Apr 2019

The soon-to-be iconic photograph of the scene, taken by Andrew J. Russell, followed, splashed across the front pages of newspapers around the world.

The picture shows dozens of railroad executives, government officials and ordinary workers surrounding two steam engines: the Central Pacific’s Jupiter from the west, on the left, and the Union Pacific’s #119 from the east, on the right. Yet despite 12,000 to 15,000 Chinese having laboured on the project from 1863 to 1869, and up to 1,000 having died while doing so, none are pictured.

Their story is part of the oral history that I and other Chinese-Americans were raised with – but official accounts scarcely mention their contribution.

Chinese railroad workers depicted in a mural on a wall in Ogden Union Station, Utah. Photo: Alan Chin

Since 2014, New York photographer and activist Corky Lee has organised an annual restaging of the 1869 photograph, in front of replica locomotives, with descendants of Chinese railroad workers and other Chinese-Americans filling the frame. This year, between 400 and 500 Chinese-Americans have made the pilgrimage, in the largest such gathering to date

“I want to pop the champagne that my grandfather could not,” says John Mark, a descendant of a Chinese railroad worker who has come from California. May Chin Ng, who has driven 3,500km (2,200 miles) from Huntington, New York, says she has come in case the sacrifice made by her ancestral countrymen is lost “on the wayside of history”.

Blackface scandal lays bare America’s racism problem

4 Feb 2019

Lee has to move the platform and ladder he is using several times to accommodate the chaotic and growing crowd before he can take this year’s photograph.

The joy and sense of delayed justice are palpable and moving. Yet the occasion remains primarily one of contemporary American patriotism. The Stars and Stripes flies at many spots along the only road to Promontory and Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, the first Chinese-American woman of cabinet rank, makes appropriate comments with anodyne phrasing: “The Central Pacific Railroad needed industrious, tireless workers and the Chinese workers answered the call with great skill and dedication.”

Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao. Photo: Alan Chin

It may have been too much to expect her to mention the disciplined and non-violent strike that the railroad workers successfully executed in 1867, as they sought the same pay as their white colleagues, or the anti-Chinese massacres and pogroms in Los Angeles and Wyoming that marred the era. After all, Utah residents and railroad fans from across the country make up the bulk of the large crowd.

The multiracial theatre group that performs As One, a musical retelling of the great narrative, are wearing the wrong kind of Chinese peasant hats and Utah senator Mitt Romney seems to be already politicking for another campaign.

A large bronze statue of a bison is unveiled; a group of children parade around, wearing red neckerchiefs in an evocation of the Wild West; and a “sheriff’s posse” make for picturesque perimeter guards on horseback. The event feels like a middle American county fair rather than a cathartic coming to terms with past injustices.

Silent no longer, South Africa’s Chinese fight back against hate speech

13 Apr 2019

Nevertheless, “I think [the Chinese labourers] would feel so happy,” Margaret Yee tells me. She is a Chinese-American resident of Salt Lake City who had great-grandfathers on both the paternal and maternal sides who worked on the railroad.

“They had no idea they could transform the USA. The Chinese built the railroad, and the railroad built America. Up in the sky they are smiling over us.”

Above us, the day’s celebrations conclude with four Air Force fighter jets roaring past, over bursting fireworks, as a brass band plays the national anthem.

Connie Young Yu shows her parents’ photographs from 50 years earlier. Photo: Alan Chin

Members of a “sheriff’s posse” act as perimeter guards at this year’s gathering. Photo: Alan Chin

Margaret Yee, a descendant of 19th century railroad workers. Photo: Alan Chin

A restored steam engine at Ogden Union Station. Photo: Alan Chin

Actors representing 19th century railroad workers and other characters perform a musical about the railroad’s construction. Photo: Alan Chin

Children in period costume attend the celebrations. Photo: Alan Chin

The bison sculpture Distant Thunder, by Utah artist Michael Coleman, is unveiled as part of the 2019 ceremonies. Photo: Alan Chin

Alan Chin was born and raised in New York City’s Chinatown. Since 1996, he has worked in China, the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Central Asia, and Ukraine, as well as extensively in the United States. He is a contributing photographer to The New York Times and many other publications, an Adjunct Professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and his work is in the collections of the Museum Of Modern Art and the Detroit Institute of Art. The New York Times twice nominated Alan for the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Kosovo conflict in 1999 and 2000.