Let me begin with a few general statements about the latest attacks on Chomsky. It is a sickening spectacle to witness private emails sent by Chomsky to a close, personal friend being used to attack him. Imagine the sordid details about a financial dispute between you and your children getting exposed to the public when you are 97 years old, suffering from a stroke, and incapable of responding. I wonder how the attackers out there would feel having their personal email being scanned for personal and political gotchas.

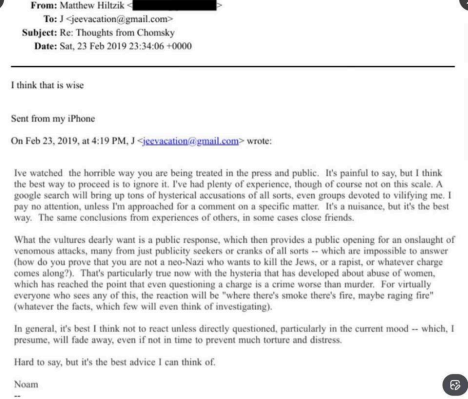

Still, if we do wish to peruse private emails, let us please do it properly, without mischaracterizing what is written. Among all the takes out there, Greg Grandin’s is probably the fairest. And yet, in its latest addendum, it contains various mischaracterizations that are worth bringing up. Most of the addendum pertains to a private email Chomsky sent Epstein, which is quoted here in full for reference.

First, areas of agreement. Grandin writes about Chomsky that “he proved strikingly incurious—or dismissive—about the real-world exploitation of children by someone in his social orbit.” Grandin also writes: “Nothing Chomsky writes in this note … suggests that Chomsky gave much thought to Brown’s reporting or to Epstein’s victims.” referring to Julie Brown’s reporting that exposed Epstein’s crimes. Indeed.

However, I have several areas of disagreement with the addendum as well. First, the framing. The addendum fails to account for the fact that the email in question above was private, and written with a strong expectation of privacy. Grandin writes his critique as though Chomsky made a public statement defending Epstein, and attacking #metoo. He contrasts the above email with Chomsky’s actions in the Faurisson affair, whereas in the Faurisson case, Chomsky went public. For instance, Grandin says “He reflexively treats emotionally wrenching matters as if they can be defused through adherence to abstract principles. In the case of Faurisson, it was free speech. With Epstein, it seems to be due process.” Given the private nature of the email, this passage rings hollow.

Grandin then states that “The message is distinguished … for Chomsky’s refusal to take seriously #metoo’s moral imperative.” This is a mischaracterization. Chomsky’s substantive points in the email including the use of the term “hysteria” in the email is not a characterization of #metoo overall, but of cancel culture specifically, and its implication on due process. Cancel culture is something that affects otherwise progressive movements like #metoo and critiquing it is not tantamount to critiquing the movement overall. It is hard to find Chomsky interviews specifically about #metoo, but a google search does yield the below response, which is his most direct take on #metoo. He describes #metoo as a “real and serious and deep problem of social pathology.” That does not sound like someone who refuses to take seriously #metoo’s moral imperative. Chomsky does caution about cancel culture, like in the email. “I think it grows out of a real and serious and deep problem of social pathology. It has exposed it and brought it to attention, brought to public attention many explicit and particular cases and so on. But I think there is a danger. The danger is confusing allegation with demonstrated action. We have to be careful to ensure that allegations have to be verified before they are used to undermine individuals and their actions and their status. So as in any such effort at uncovering improper, inappropriate and sometimes criminal activities, there always has to be a background of recognition that there’s a difference between allegation and demonstration.”

Grandin goes on to write: “he excused Epstein with the thinnest proceduralism (due process, presumption of innocence, “he served his sentence”), thus avoiding moral claims raised by the #metoo movement.” Grandin previously states, correctly, that: “Chomsky doesn’t deny Epstein’s crimes, defend Epstein’s actions, or argue that they are exaggerated.” If Chomsky doesn’t deny Epstein’s crimes, then he cannot be excusing Epstein either.

It is undeniable that Chomsky’s email merits criticism, and Grandin’s addendum is correct to address it. There is an environment of hysteria that surrounds Chomsky now. For instance, Jeffrey St Clair makes the absurd charge that Chomsky “shames the victims as hysterics.”

Grandin’s response is fairer for sure. It is a telling comment on the sad state of our discourse that the fairest take around is overstated.

The Chomsky/Epstein Puzzle

Noam Chomsky’s life and work cannot be understood without taking into account his militarily-funded linguistics research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). There were, I believe, always two ‘Noam Chomskys’ – one working for the US military and the other working tirelessly against that same military. This contradiction cannot explain every aspect of Chomsky’s puzzling friendship with Jeffrey Epstein. But it is the underlying contradiction that helps us understand why someone as radical as Chomsky ended up being involved with someone as reactionary as Epstein.

In May 2023, when it was first revealed that Chomsky had met with Epstein ‘a number of times’, the exact nature of their relationship wasn’t clear. Such vagueness meant that those of us who had always admired his anti-militarist politics could still feel inspired by his critiques of US power, particularly after Israel set out to destroy Gaza, with full US support, in October that year.

Anyone who reads the correspondence between Chomsky and Epstein in the January 2026 release of the Epstein files, however, will now find it difficult to respect Chomsky’s opinions on Gaza or anything else.

One email from Chomsky and his second wife Valeria describes the couple’s friendship with Epstein as ‘deep and sincere and everlasting’. Another from Valeria describes Epstein as: ‘our best friend. I mean “the” one.’ Meanwhile other messages – signed only by Chomsky himself – are equally generous to the convicted sex offender, saying, for example, ‘we’re with you all the way’ and ‘you’re constantly with us in spirit and in our thoughts.’

Other documents suggest that Chomsky visited Epstein’s properties not only in New York but also in New Mexico and Paris. The files even show that shortly before Epstein’s arrest and death, in July and August 2019, Chomsky was still intending to be interviewed for a documentary that Epstein was making. It seems that Chomsky really was loyal to Epstein until the end. The question is why.

In the years following his 2008 prison sentence, Epstein claimed to have ‘collected the world’s smartest people’. He talked about arranging a dinner party with ‘Noam Chomsky, the movie director Woody Allen, former president Bill Clinton, and the living God, the Dalai Lama.’ This wasn’t idle fantasizing. As a way to both clean up his public image and to impress other multi-millionaires, Epstein was quite serious about befriending such celebrities.

So it’s clear why Epstein wanted to befriend Chomsky. It’s less clear how Chomsky could justify any association with Epstein, even if his academic colleagues were meeting with him in the hope of attracting donations.

The simplest explanation is that Epstein worked hard to manipulate and befriend Chomsky and his wife by offering them financial services, and at one point offering them a place to live. Meanwhile, Chomsky was particularly vulnerable to such offers because he’d found himself in a highly distressing family dispute over money – a dispute that the 89-year old described as the ‘worst thing that’s ever happened to me’.

This is a striking statement considering that Chomsky had earlier spent two traumatic years caring for his first wife while she suffered and died from brain cancer. By late 2018, this series of tragic events led to a shocking and surreal situation in which, in various email chains, Epstein was advising Chomsky on his painful dispute with his family, while Chomsky was advising Epstein on how to respond to press coverage about his history of sexual abuse.

Some years later, in May 2023, when confronted by journalists about his involvement with Epstein, Chomsky mentioned none of this. Instead, he explained his behaviour by saying (a) that Epstein had ‘served his sentence, which wiped the slate clean’ and (b) that ‘far worse criminals’ were associated with MIT. When speaking to the Harvard Crimson, Chomsky was still more forthright, pointing out that MIT’s donors included the ‘worst criminals’ and that he’d met all sorts of people in his lifetime including ‘major war criminals’ and didn’t regret having met any of them.

In a private email from the same period, Chomsky claimed he was simply unaware of the more serious accusations against Epstein, writing that although ‘lurid stories and charges’ did come out in 2019, none of the academics who knew Epstein had a ‘remote hint of anything like that, and all were quite shocked, sometimes skeptical because he [sic] was so remote from anything they’d ever heard of.’

Many commentators have, understandably, found it difficult to believe that the world’s leading critic of the US establishment could have been so unaware of who Jeffrey Epstein really was. Some have blamed his behaviour on a blindness both to gender issues and to problems of sexual violence and abuse. The fact that in one of his 2019 emails to Epstein, Chomsky referred to ‘the hysteria that has developed about abuse of women, which has reached the point that even questioning a charge is a crime worse than murder’ certainly adds credence to this charge.

As an anthropologist who focuses on gender relations and their role in the origins of language, I’m well aware of Chomsky’s gender blindness. But, that said, I’m also convinced that his advocacy of progressive and left-wing causes was genuinely intended: it was always one side of the celebrated academic. But there was also another side. To understand that side of Chomsky, it helps if we grasp that in one sense, the Epstein connection was business as usual. In his professional life at MIT, Chomsky was well used to finding positive features in people he considered to be criminals.

A telling example is John Deutch, an MIT scientist who played a leading role in the Pentagon’s nuclear and chemical weapons strategy before becoming Director of the CIA. As a committed anti-militarist, Chomsky must have judged Deutch to be some sort of ‘war criminal’. Yet as an MIT scientist, he felt able to praise Deutch in almost as glowing terms as he would later use about Epstein. While disagreeing on many issues, explained Chomsky, he and Deutch were ‘friends and got along fine’. When the New York Times asked Chomsky about Deutch, his words could hardly have been warmer:

‘He has more honesty and integrity than anyone I’ve ever met in academic life, or any other life. … If somebody’s got to be running the CIA, I’m glad it’s him.’

War research at MIT

Deutch wasn’t the only figure in the US military establishment that Chomsky got along with at his university. As he explained in 1989: ‘I’m at MIT, so I’m always talking to the scientists who work on missiles for the Pentagon.’

Beneath all this friendliness, Chomsky was well aware of the criminality of his MIT colleagues. In 1969, at the height of student protests against the Vietnam War, he even compared some of them to ‘Nazi scientists’ in view of their indifference to the millions who would die if the nuclear missiles they were designing were ever used. But, just as he got along with Epstein and Deutch, Chomsky somehow found a way to get along with most of those he met at MIT – whether they were war scientists or anti-war students.

MIT’s anti-war students were particularly damning of their university’s military associations, writing that:

‘MIT isn’t a center for scientific and social research to serve humanity. It’s a part of the US war machine. … MIT’s purpose is to provide research, consulting services and trained personnel for the US government and the major corporations – research, services, and personnel which enable them to maintain their control over the people of the world.’

The energy and radicalism of MIT’s student protesters comes across powerfully in a 2022 documentary entitled MIT Regressions. At one point, the documentary reminds us why Chomsky was recruited to work at MIT in the first place: he was initially employed to conduct ‘research for the Cold War’ by Dr. Jerome Wiesner, a Pentagon scientist who went on to become a top adviser to President Kennedy.

Had the documentary delved further, it might have mentioned Dr. Wiesner’s key role in setting up the US’s entire nuclear missile programme, including its command and control systems. There can be little doubt that Wiesner and his Pentagon colleagues kept funding Chomsky’s linguistics research in the hope that it would eventually pay dividends in terms of command and control.

Despite Chomsky’s well-known claims, his linguistics research was always shaped more by military agendas than with any attempt to understand the bases of everyday human language. Various documents from the 1960s and 1970s are quite clear that the Pentagon’s scientists hoped to use Chomsky’s theories for what Lieutenant Jay Keyser called a ‘control language’ for electronic equipment and what Colonel Anthony Debons called ‘languages for computer operations in military command and control systems’. Jay Keyser – who would later become Chomsky’s long-standing friend and head of MIT’s linguistics department – was quite explicit that Chomsky’s theoretical work might one day be useful in the computerised control of missiles and aircraft, including B-58 nuclear-armed bombers.

Linguists at an MIT-offshoot called the MITRE Corporation were particularly interested in Chomsky’s ideas. As their lead researcher, Donald Walker, wrote, ‘Our linguistic inspiration was (and still is) Chomsky’s transformational approach.’ As many as ten of Chomsky’s linguistics students conducted research at MITRE – work that was always intended to support the ‘development of US Air Force-supplied command and control systems’. One of these students, Barbara Partee, explained to me that Walker persuaded the military to hire them on the basis that:

‘In the event of a nuclear war, the generals would be underground with some computers trying to manage things, and that it would probably be easier to teach computers to understand English than to teach the generals to program.’

In the light of this, and especially considering MITRE’s involvement in the Vietnam War, the one institution we might have expected the anti-militarist Chomsky to avoid would have been the MITRE Corporation. It appears, however, that Chomsky worked as a ‘consultant’ both for MITRE and for the SDC, another corporation involved in nuclear weapons command and control.

Fortunately, in view of Chomsky’s anti-militarist conscience, his linguistics research – mostly in MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE) – was years away from being developed into actual weapons systems. But despite this, I doubt whether his conscience was ever completely clear. It is well documented that Chomsky felt guilty for doing too little to oppose the Vietnam War and, in 1967, he considered ‘resigning from MIT’ in view of its intimate links with the Pentagon.

Of course, Chomsky did not resign. Rather, he went into a kind of denial about the nature of his workplace, even repeating MIT’s official line that no military work was conducted ‘on campus’. He did this although he surely knew that it was the RLE’s ‘on campus’ research that provided the theoretical basis for the ‘off campus’ production of weapons systems at places like MITRE and the SDC.

Despite this denial, Chomsky always understood that his own workplace, the RLE, was a ‘military lab’. In my view, it was his understandable discomfort about working in the pay of the military that motivated him to devote so much of his time and energy into a lifetime of activism against that same military.

I also suspect that it was such moral anxieties that intensified the striking abstraction of Chomsky’s linguistic theories – theories that not only required constant discarding and replacement but appear almost designed to prove unworkable. By ‘unworkable’ I mean so abstract and other-worldly as to ensure that no scientist could use them for anything at all, let alone weapons command and control.

This argument is controversial. But I have come across no better way to explain how Chomsky’s anti-militarist politics and his other-worldly linguistics ultimately connect up – a question that has puzzled his supporters and critics alike.

Chomsky’s ‘other-worldly’ linguistics

Let me explain what I mean by ‘other-worldly’. Chomsky’s understanding of language is that it derives from a ‘language organ’ in the brain that he likens to Plato’s or Descartes’ concept of the soul. In Chomsky’s view, to talk of language emerging in our species through Darwinian evolution would be like discussing the evolution of the soul. Like the soul, Chomsky says, language is either present or not present – you cannot have half a soul. So it makes no sense to envisage language evolving by degrees.

In response to those of us who have asked him how he thinks language really did emerge, Chomsky has offered little more than what he terms a ‘fairy story’: the brain of a single prehistoric human was ‘rewired, perhaps by some slight mutation’. It all happened suddenly and without building on any evolutionary precursor.

Again like the soul – if we are to believe Chomsky – language has no special connection with communication. It can be used for communication ‘as can anything people do’ but, Chomsky says, ‘language is not properly regarded as a system of communication’. He then adds the still stranger claim that the concepts we use in language, such as ‘book’ or ‘carburettor’, have existed in the human brain since the emergence of our species tens of millennia before real books or carburettors even existed.

To claim that language did not evolve for communication, or that prehistoric humans were hardwired with such concepts as ‘book’ or ‘carburettor’, simply makes no sense. For this and other reasons, many contemporary linguists have now concluded that Chomsky’s theories are completely unworkable, having reached what the eminent evolutionary psychologist Michael Tomasello calls ‘a final impasse’. But the question remains, why did someone as intelligent as Chomsky so consistently espouse such ideas?

In my own book on this topic, I argue that by equating language with something like the soul, Chomsky was able to slip unnoticeably from real science to a kind of scientistic theology, insulating his linguistics from any possible military use. Although this made his linguistic theories completely impractical, to Chomsky the moral advantages were clear: You cannot kill anyone by weaponizing the soul!

The ‘Two Chomskys’

Chomsky’s sophisticated manoeuvre to insulate his linguistics from any risk of military use – even while remaining employed at MIT – proved highly successful. His equally impressive manoeuvre to become a tireless campaigner against the US military, even having spent the early decades of his career in the pay of that same military, was also successful. Indeed, these manoeuvres were so successful there now seemed to be ‘Two Chomskys’: the MIT professor working for the US establishment – a person quite happy to associate with people like Deutch and Wiesner – and the anti-militarist campaigner working tirelessly against that same establishment.

It was the first Chomsky – the corruptible MIT professor – who went along with the official line that the university conducted no military work ‘on campus’. And it was the second – the principled campaigner – who seriously considered resigning from MIT in protest at his university’s military involvement.

Continuing with this dualism, in my view it was the first Chomsky, the corruptible MIT professor, who went along with his academic colleagues in socialising with and befriending Epstein and who, in May 2023, justified this behaviour on the grounds that the sex offender had ‘served his sentence’. And it was the second Chomsky, the tireless campaigner, who strove to be the mirror image of all this. This was the figure whom Chomsky’s former assistant, Bev Stohl, is describing when she says in response to his growing chorus of critics: ‘I observed his total dedication to humankind. He barely slept [and] had to be reminded to eat.’

To what extent this rather unhealthy lifestyle was a factor in Chomsky’s debilitating stroke in June 2023 is hard to say. It’s even more difficult to know if emotional stress – perhaps caused by the realisation that he’d made an indefensible mistake – was also a factor. But the fact that Chomsky suffered his stroke only a few weeks after being confronted by journalists questioning him about Epstein might suggest that Chomsky had, at long last, realised the terrible error he had made in his choice of friends.

Chomsky was never the perfectly principled anarchist intellectual admired by so many of his followers. In my view, had he been that ideal figure he would have resigned from MIT long ago. Yet, had he done so, he would never have come to know the US military establishment from the inside in a way that enabled him to become that establishment’s most knowledgeable and assured critic.

Whatever one thinks of his get-togethers with Steve Bannon and Ehud Barak – friendly occasions in each case arranged by Epstein – these meetings surely made Chomsky’s commentaries on US and global politics even more knowledgeable and assured.

I certainly miss these commentaries – in key respects a ray of sanity in an increasingly deranged world. A few months before his devastating stroke, Chomsky wrote these words:

‘Ukraine is being devastated. … The threat of escalation to nuclear war intensifies. Perhaps worst of all, in terms of long-term consequences, the meager efforts to address global heating have been largely reversed.

Some are doing fine. The US military and fossil fuel industries are drowning in profit, with great prospects for their missions of destruction many years ahead. … Meanwhile, scarce resources that are desperately needed to salvage a livable world, and to create a much better one, are being wasted in destruction and slaughter, and planning for even greater catastrophes.’

This is Chomsky at his best, speaking the plain truth about the state of our world and accurately predicting ‘even greater catastrophes’ just months before the start of the US-sponsored genocide in Gaza.

For well over fifty years, the ‘Two Chomskys’ – the establishment scientist loyal to MIT and the anti-establishment activist distrustful of anyone with wealth or power – seemed to live quite separate lives. Photographs of Chomsky with Epstein on the disgraced financier’s private jet have now exploded that separation, revealing Chomsky’s double life for all to see.

For some people, Chomsky’s friendship with Epstein will discourage them from reading or listening to him ever again. For others, his insights into global politics are too valuable to be ignored. Either way, I hope this article has helped readers better understand both our highly conflicted world and the price paid by Chomsky in his life-long struggle to rebel against it while simultaneously fitting into it.

No comments:

Post a Comment