OBIT

Sir Sean Connery: An imperfect man, but the perfect star

He was the milkman’s boy raised in the fumes of McEwan’s brewery and the North British Rubberworks, who ascended the heights of Hollywood to become the most famous living Scot.

By Martyn Mclaughlin

Saturday, 31st October 2020,

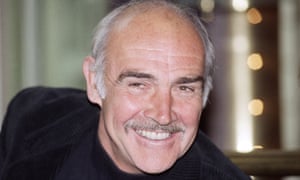

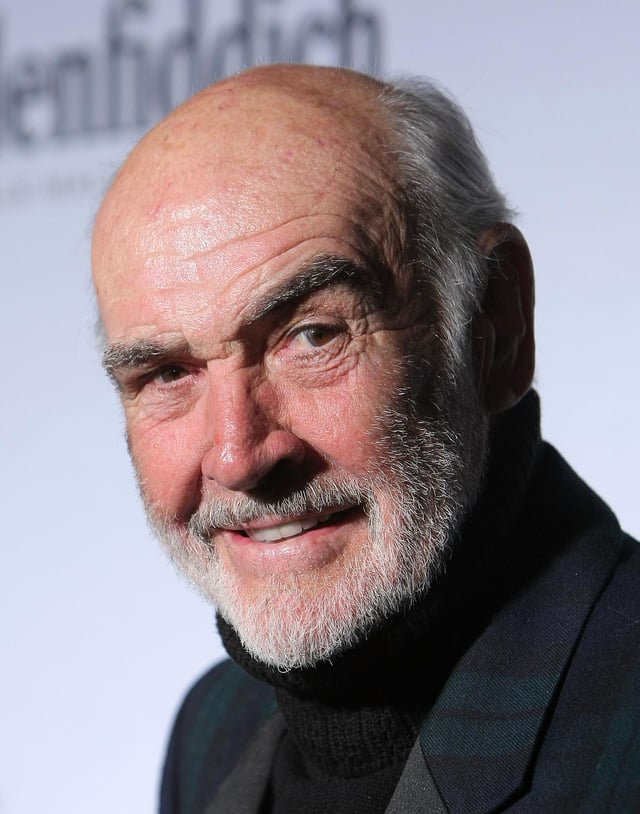

Sir Sean Connery pictured in New York in 2009. Picture: Michael Loccisano/Getty

The life of Sir Sean Connery, who has died at the age of 90, was a remarkable and improbable ride. He will be immortalised as the actor who defined the character of James Bond, and carved out a status as Scotland’s greatest bona fide film star. He will also be remembered as the man who was, and steadfastly remained, Big Tam.

Nearly twenty years have passed since Connery’s final on-screen performance, and yet he left behind a filmography to rival any leading man in the 20th century. It spanned 58 years and roles as diverse as a Spanish hidalgo, one of England’s most famous kings, a Russian submarine captain, and a legendary Greek ruler. The accent never deviated. The script seldom mattered. People paid to see Connery.

No Scot achieved the level of his fame, and perhaps no one will. What made Connery’s all the more remarkable is that he refused to court it. He let his aura do the talking.

The nature and allure of that elusive quality is difficult to define, as evidenced in the flurry of fulsome tributes paid to Connery in the past few hours. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon described it as a “towering presence,” while Daniel Craig, the current Bond, said Connery’s radiance could be measured only in “megawatts.”

Both assessments are true, and yet incomplete. Whatever Connery had, it was fully formed long before he set foot in an Aston Martin DB5. A few years back, I spoke to the artist, Richard Demarco, one of Connery’s childhood friends. The young actor had posed for him as a life model, and Demarco recalled a natural dignity to the way he held himself.

“It was obvious Tommy was not going to be a French polisher,” Demarco told me. “But then, all he had to do was stand still and look beautiful.”

On screen, Connery fused a combustible blend of elegance and menace, and moved like a panther. The grit and danger were ever present in his Bond, and the supporting Oscar he won for his turn in The Untouchables proved deserved recognition of an understated and often underappreciated acting style. But it was arguably his films with Sidney Lumet which best exploited Connery’s innate physical authority - the bedrock of his success.

This quality granted him a leading man presence comparable to Cary Grant, James Cagney, and Gary Cooper. Connery’s greatest achievement, perhaps, was to prove so effortlessly that a working class Scot, the son of a cleaner and a factory worker, belonged in their company

Off screen, the same balance was not always so easy to strike. He was difficult company at times, both among strangers as well as those who classed themselves as his friends. Despite publishing his autobiography Connery was not a man given to self-revelation.

As the late William McIlvanney once observed, Connery never mistook himself for any image he was supposed to have at any given time. Any image he acquired was just part of him, not the other way round.

Indeed, Connery had greater influence over Bond’s Scots heritage than has been acknowledged. It was only after seeing him in the film adaptation of Dr No that Ian Fleming fleshed out his protagonist’s backstory in You Only Live Twice.

And from a man descended from Irish travelling stock, whose great grandfather eked out a miserable living as a bare knuckle fighter, there were darker legacies. Fits of jealousy, bitterness, and violence; forces he sometimes trained against those closest to him.

One of the ironies of Connery’s life was his vexed relationship with the very things that defined him - Bond, Scotland and women.

He resented the Broccoli family for the money he had received for turning Bond into one of the world’s most successful - and profitable - film franchises.

In the early 1980s, Harry Saltzman, a co-producer of the films, took seriously ill. According to Joe McGrath, the Scottish film director, Connery received the news at a card table in a casino.

“Sean, Harry’s had a stroke,” he was told. “He’s paralysed down one side.” Connery, still looking at his cards, replied: “Good. I hope he’s paralysed down the other side tomorrow.” Asked later if the story was true, he said simply, 'Yes.”

Connery was subject to accusations of misogyny over the years, including by his ex-wife, Diane Cilento, who said he subjected her to physical and mental abuse. He once advocated hitting women with an “open handed slap” in a 1975 interview with Playboy, and spent much of the next 45 years expressing regret.

As Connery became increasingly politically active, he was also charged with claims of hypocrisy for advocating the cause of Scottish independence from far-flung climes. His interjections in the debate over his homeland’s future were once dismissed by Brian Wilson, the former Labour MP, as “the view from a Marbella saloon bar.”

But Connery’s love for his country, and his desire for constitutional change, never dimmed. Even in the twilight of his life, spent in sun-dappled Lyford Cay, a private gated community in the Bahamas, he yearned for both.

None of this contradiction and darkness inherent in Connery’s character dulled the brightness of his star. Maybe because they helped create it. He was, after all, the emblem of a particular strain of masculinity that was once revered. Nowadays, it is openly questioned, and fading fast from view.

In the age of #MeToo, it seems inconceivable that his star would ascend under the same circumstances. But then, no young actor nowadays would begin their working life at the age of nine, rising at 5am from the squalor of a cramped tenement to deliver milk in a handcart.

Connery was, in many ways, an Imperfect man. But he was, and will remain, the perfect star.

The life of Sir Sean Connery, who has died at the age of 90, was a remarkable and improbable ride. He will be immortalised as the actor who defined the character of James Bond, and carved out a status as Scotland’s greatest bona fide film star. He will also be remembered as the man who was, and steadfastly remained, Big Tam.

Nearly twenty years have passed since Connery’s final on-screen performance, and yet he left behind a filmography to rival any leading man in the 20th century. It spanned 58 years and roles as diverse as a Spanish hidalgo, one of England’s most famous kings, a Russian submarine captain, and a legendary Greek ruler. The accent never deviated. The script seldom mattered. People paid to see Connery.

No Scot achieved the level of his fame, and perhaps no one will. What made Connery’s all the more remarkable is that he refused to court it. He let his aura do the talking.

The nature and allure of that elusive quality is difficult to define, as evidenced in the flurry of fulsome tributes paid to Connery in the past few hours. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon described it as a “towering presence,” while Daniel Craig, the current Bond, said Connery’s radiance could be measured only in “megawatts.”

Both assessments are true, and yet incomplete. Whatever Connery had, it was fully formed long before he set foot in an Aston Martin DB5. A few years back, I spoke to the artist, Richard Demarco, one of Connery’s childhood friends. The young actor had posed for him as a life model, and Demarco recalled a natural dignity to the way he held himself.

“It was obvious Tommy was not going to be a French polisher,” Demarco told me. “But then, all he had to do was stand still and look beautiful.”

On screen, Connery fused a combustible blend of elegance and menace, and moved like a panther. The grit and danger were ever present in his Bond, and the supporting Oscar he won for his turn in The Untouchables proved deserved recognition of an understated and often underappreciated acting style. But it was arguably his films with Sidney Lumet which best exploited Connery’s innate physical authority - the bedrock of his success.

This quality granted him a leading man presence comparable to Cary Grant, James Cagney, and Gary Cooper. Connery’s greatest achievement, perhaps, was to prove so effortlessly that a working class Scot, the son of a cleaner and a factory worker, belonged in their company

Off screen, the same balance was not always so easy to strike. He was difficult company at times, both among strangers as well as those who classed themselves as his friends. Despite publishing his autobiography Connery was not a man given to self-revelation.

As the late William McIlvanney once observed, Connery never mistook himself for any image he was supposed to have at any given time. Any image he acquired was just part of him, not the other way round.

Indeed, Connery had greater influence over Bond’s Scots heritage than has been acknowledged. It was only after seeing him in the film adaptation of Dr No that Ian Fleming fleshed out his protagonist’s backstory in You Only Live Twice.

And from a man descended from Irish travelling stock, whose great grandfather eked out a miserable living as a bare knuckle fighter, there were darker legacies. Fits of jealousy, bitterness, and violence; forces he sometimes trained against those closest to him.

One of the ironies of Connery’s life was his vexed relationship with the very things that defined him - Bond, Scotland and women.

He resented the Broccoli family for the money he had received for turning Bond into one of the world’s most successful - and profitable - film franchises.

In the early 1980s, Harry Saltzman, a co-producer of the films, took seriously ill. According to Joe McGrath, the Scottish film director, Connery received the news at a card table in a casino.

“Sean, Harry’s had a stroke,” he was told. “He’s paralysed down one side.” Connery, still looking at his cards, replied: “Good. I hope he’s paralysed down the other side tomorrow.” Asked later if the story was true, he said simply, 'Yes.”

Connery was subject to accusations of misogyny over the years, including by his ex-wife, Diane Cilento, who said he subjected her to physical and mental abuse. He once advocated hitting women with an “open handed slap” in a 1975 interview with Playboy, and spent much of the next 45 years expressing regret.

As Connery became increasingly politically active, he was also charged with claims of hypocrisy for advocating the cause of Scottish independence from far-flung climes. His interjections in the debate over his homeland’s future were once dismissed by Brian Wilson, the former Labour MP, as “the view from a Marbella saloon bar.”

But Connery’s love for his country, and his desire for constitutional change, never dimmed. Even in the twilight of his life, spent in sun-dappled Lyford Cay, a private gated community in the Bahamas, he yearned for both.

None of this contradiction and darkness inherent in Connery’s character dulled the brightness of his star. Maybe because they helped create it. He was, after all, the emblem of a particular strain of masculinity that was once revered. Nowadays, it is openly questioned, and fading fast from view.

In the age of #MeToo, it seems inconceivable that his star would ascend under the same circumstances. But then, no young actor nowadays would begin their working life at the age of nine, rising at 5am from the squalor of a cramped tenement to deliver milk in a handcart.

Connery was, in many ways, an Imperfect man. But he was, and will remain, the perfect star.

Sean Connery, a lion of cinema whose roar went beyond Bond

By JAKE COYLE

1 of 4

FILE - This March 4, 1992 file photo shows actor Sean Connery during a news conference in Hamburg, Germany. Connery, considered by many to have been the best James Bond, has died aged 90, according to an announcement from his family.(AP Photo/Christian Eggers, File)

Writing an appreciation of Sean Connery feels inevitably inadequate compared to experiencing the real thing. To glimpse his magnetism, you might turn to a photograph of him in a tailored suit, leaning against an Aston Martin. You’d probably get more of his menacing charisma by pulling up the “Chicago way” scene from “The Untouchables.”

It might be enough simply to say: The king is dead.

As a lion of movies for half a century, Connery’s talent was manifest. He was famously cast as James Bond without a screen test. It was that obvious. And from then on, in even the lesser films, Connery, who died Saturday at 90, was never out of place on screen. His presence was absolute. Noting his supreme confidence, the late film critic Pauline Kael once wrote, “I don’t know any man since Cary Grant that men have wanted to be so much.”

1 of 4

FILE - This March 4, 1992 file photo shows actor Sean Connery during a news conference in Hamburg, Germany. Connery, considered by many to have been the best James Bond, has died aged 90, according to an announcement from his family.(AP Photo/Christian Eggers, File)

Writing an appreciation of Sean Connery feels inevitably inadequate compared to experiencing the real thing. To glimpse his magnetism, you might turn to a photograph of him in a tailored suit, leaning against an Aston Martin. You’d probably get more of his menacing charisma by pulling up the “Chicago way” scene from “The Untouchables.”

It might be enough simply to say: The king is dead.

As a lion of movies for half a century, Connery’s talent was manifest. He was famously cast as James Bond without a screen test. It was that obvious. And from then on, in even the lesser films, Connery, who died Saturday at 90, was never out of place on screen. His presence was absolute. Noting his supreme confidence, the late film critic Pauline Kael once wrote, “I don’t know any man since Cary Grant that men have wanted to be so much.”

As a more earthy, macho movie-star ideal, Connery was so beloved that he was shared, like folklore, between generations. It helped that he never seemed to be appealing to the audience, or to anybody, for anything. With raised eyebrows and roguish wisecracks, there was little that Connery (nearly always the lead) didn’t command. And to a certain extent, that cocksureness shaped his career, too.

Connery, 32 when “Dr. No” came out,” had already lived through World War II. Born into poverty in Edinburgh, he left school at age 13 during the war and worked as a laborer and a bricklayer before he donned the tuxedo. He saw Bond, too, as a product of the war.

“Bond came on the scene after the War, at a time when people were fed up with rationing and drab times and utility clothes and a predominantly gray color in life,” Connery, who served in the British Navy as a teenager, told Playboy in 1965. “Along comes this character who cuts right through all that like a very hot knife through butter, with his clothing and his cars and his wine and his women.”

Long after achieving fame, Connery contentedly gave it up. He spent his final two decades cheerfully retired in the Caribbean, often playing golf with his wife, unimpressed and little tempted by more modern Hollywood productions. (He said he was “fed up with the idiots.”)

There was irony in that. Connery, as the original cinema Bond, did much to make the style and tone of today’s movie franchises — even if few carry a lick of Connery’s danger. His Bond heir Daniel Craig on Saturday credited Connery with helping “create the modern blockbuster.” It’s hard to imagine the suave secret-service spy would have ever become a cultural force if the franchise hadn’t from the start traded on its star’s brutal charm. Connery crucially added humor to Ian Fleming’s pages, along with a dash of cruelty.

Connery’s Bond became etched as an icon of its era, one increasingly distant from today. He was the epitome of a dashing, womanizing, macho image that loomed over the second half of the 20th century. Connery differed from his character in many respects but not all. In that same Playboy interview, he explained why he believed hitting a woman with an open fist was justifiable.

Bond is the first word on Connery but it’s certainly not the last. Against the pleas of fans, he departed the character at 41 (he was later coaxed back for 1983’s “Never Say Never Again”), refusing to be typecast. His best and most interesting work all came after.

“The Hill” (1965) was the first of five films with Sidney Lumet (the others were “The Anderson Tapes,” “The Offense,” “Murder on the Orient Express” and “Family Business”), and while it’s less seen than many of Connery’s, it remains possibly the best expression of the actor’s rugged power. He plays a prisoner of indomitable strength and defiance jailed in a sadistic British Army WWII military prison in the scorching Libyan desert.

He was a soldier again a decade later in John Huston’s “The Man Who Would Be King,” based on the Rudyard Kipling short story, playing a military officer who’s embraced as a god in Kafiristan, an impression he struggles to maintain. It’s a perfect role and performance for Connery, whose best work came when he — this former bodybuilder of unimpeachable force and magnetism — was humbled.

Connery’s confidence came through most dramatically when it was challenged by foes more formidable than a Bond villain. In his Oscar-winning performance in Brian De Palma’s Prohibition-era crime film, “The Untouchables,” he’s alive to Al Capone’s threat, telling Kevin Costner’s Treasury Department agent: “You see what I’m saying is, what are you prepared to do?”

Accepting the Academy Award, Connery addressed his wife since 1975, Micheline Roquebrune. “In winning this award, it creates a certain dilemma because I had decided that if I had the good fortune to win, that I would give it to my wife, who deserves it,” he said. “But, this evening, I discovered backstage that they’re worth $15,000 — now I am not so sure. Micheline, I am only kidding. It’s yours.”

Connery aged well as an actor, crafting more diverse and inquisitive portraits of masculinity. He played an aging Robin Hood, with Audrey Hepburn, in “Robin and Marian” (1976), a combustible submarine captain in John McTiernan’s “The Hunt for Red October” and a lovable, playful father to Harrison Ford in Steven Spielberg’s “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” (1989).

Another “Indiana Jones,” Connery said, had been the only thing that really tempted him to come out of retirement. That could be because the glint of mischief that accompanied nearly every Connery performance was so present in “The Last Crusade.” Connery always left you feeling if not shaken then very happily stirred.

___

AP Film Writer Jake Coyle