December 7, 2020

Did the COVID-19 pandemic doom Donald Trump’s re-election? Our study examining the effect of COVID-19 cases on county-level voting in the United States shows that the pandemic led to Trump’s defeat on Nov. 3.

Our analysis suggests that, all things being equal, Trump would likely have won re-election if COVID-19 cases had been between five and 10 per cent lower. In particular, Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — which President-elect Joe Biden won by a slim margin — would have remained red if cases had been five per cent lower.

Trump would have also added Michigan to this list if cases had been 10 per cent lower.

This finding is at odds with some initial news analyses that indicated regions with the worst COVID-19 outbreaks voted for Trump.

Join thousands of Canadians who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

In fact, national polls and academic studies suggest that Trump’s voters are significantly less likely to wear masks and comply with social distancing, which in turn increase the probability of outbreaks. So Trump voters in Trump-friendly jurisdictions, due to their aversion to wearing masks, had more dramatic COVID-19 outbreaks leading up to the election.

Our analysis suggests that, all things being equal, Trump would likely have won re-election if COVID-19 cases had been between five and 10 per cent lower. In particular, Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — which President-elect Joe Biden won by a slim margin — would have remained red if cases had been five per cent lower.

Trump would have also added Michigan to this list if cases had been 10 per cent lower.

This finding is at odds with some initial news analyses that indicated regions with the worst COVID-19 outbreaks voted for Trump.

Join thousands of Canadians who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

In fact, national polls and academic studies suggest that Trump’s voters are significantly less likely to wear masks and comply with social distancing, which in turn increase the probability of outbreaks. So Trump voters in Trump-friendly jurisdictions, due to their aversion to wearing masks, had more dramatic COVID-19 outbreaks leading up to the election.

Mostly maskless Trump supporters gather for a rally in Miami on Nov. 1, 2020. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

The COVID-19 effect

We estimated the effect of COVID-19 cases and deaths on the change in Trump’s county-level share of votes between 2016 and 2020.

To account for potential alternative explanations, we included a large number of pandemic-related controls, including measures of social distancing, that captured differences in virus containment measures that might have affected cases and had an impact on Trump support.

In an attempt to measure the causal relationship between COVID-19 cases and votes for Trump, we used the share of workers employed in meat-processing factories associated with COVID-19 outbreaks as a source of external variations in COVID-19 cases. Doing so mitigated the risk of a spurious correlation between the incidence of the pandemic and Trump support.

We found that voters living in counties with a high number of COVID-19 cases were less likely to vote for Trump. This effect appears strongest in urban areas and in swing states. The strong results in cities are likely driven by suburban areas, where Trump performed much better in 2016 than he did in 2020.

These results suggest that some Trump voters may have switched to Biden because of the pandemic. In addition, we found no evidence that counties with a large increase in unemployment compared to the pre-pandemic period were more likely to switch from Trump to Biden. This last result seems to indicate that health concerns trumped — pardon the pun — economic conditions.

Retrospective voting

Now that we have an answer to our initial question, how can we explain these results? There are two possible explanations as to why the pandemic decided the 2020 presidential election.

On the one hand, voters may have electorally sanctioned Trump for how he handled the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, the U.S. economy was performing well, and Trump, while extremely polarizing, enjoyed strong support among Republican voters.

The virus changed the narrative, and Trump’s response was widely criticized. He consistently downplayed the risks of the disease, refused to embrace basic health precautions such as masks and repeatedly criticized epidemiologists and scientists, including those advising him.

Protesters stand outside the White House to demonstrate against Trump’s lax handling of COVID-19. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

His response, in contrast to leaders in other developed democracies, was profoundly unsuccessful, as the recent dramatic surge of cases has demonstrated once more.

This explanation is in line with a well-established theory in political science: retrospective voting. In a nutshell, that’s when citizens evaluate and vote based on their perceptions of the incumbent’s performance. If incumbents are perceived as incompetent, citizens vote them out of office.

While intuitive, this theory has not been always empirically true. However, it does seem to have some value in explaining the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

Economic fears, need of social safety net

On the other hand, some voters may have switched to Biden from Trump due to the pandemic-fuelled recession. A severe public health threat and major economic losses may have shifted preferences in favour of an expansion of the social safety net, including health care and unemployment insurance programs.

His response, in contrast to leaders in other developed democracies, was profoundly unsuccessful, as the recent dramatic surge of cases has demonstrated once more.

This explanation is in line with a well-established theory in political science: retrospective voting. In a nutshell, that’s when citizens evaluate and vote based on their perceptions of the incumbent’s performance. If incumbents are perceived as incompetent, citizens vote them out of office.

While intuitive, this theory has not been always empirically true. However, it does seem to have some value in explaining the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

Economic fears, need of social safety net

On the other hand, some voters may have switched to Biden from Trump due to the pandemic-fuelled recession. A severe public health threat and major economic losses may have shifted preferences in favour of an expansion of the social safety net, including health care and unemployment insurance programs.

Volunteers load boxes of food into cars during a Greater Pittsburgh Community Food bank drive-up food distribution in Duquesne, Pa., on Nov. 23, 2020. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)

Since the Democratic Party and its presidential candidate are more likely to champion these policies, Biden reaped the electoral benefits of this switch in voters’ preferences.

This explanation is in line with studies that suggest political preferences are shaped by personal experience. The same studies show this switch in political preferences is often long-lasting.

For instance, there is evidence that people growing up in a recession are more likely to favour state intervention and large social welfare programs.

This second explanation would be good news for the Democratic Party even in subsequent elections, when, hopefully, the pandemic will not dictate the narrative of the campaign but may still be fresh in the memories of voters.

Authors

Since the Democratic Party and its presidential candidate are more likely to champion these policies, Biden reaped the electoral benefits of this switch in voters’ preferences.

This explanation is in line with studies that suggest political preferences are shaped by personal experience. The same studies show this switch in political preferences is often long-lasting.

For instance, there is evidence that people growing up in a recession are more likely to favour state intervention and large social welfare programs.

This second explanation would be good news for the Democratic Party even in subsequent elections, when, hopefully, the pandemic will not dictate the narrative of the campaign but may still be fresh in the memories of voters.

Authors

Abel Brodeur

Associate professor, health economics, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Associate professor, health economics, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Leonardo Baccini

Associate professor, political science, McGill University

Associate professor, political science, McGill University

Leonardo Baccini receives funding from SSHRC (Canada).

Stephen Weymouth

Associate professor, international business, Georgetown University

Associate professor, international business, Georgetown University

Donald Trump: how COVID-19 killed his hope of re-election – new research

November 30, 2020

The sun sets on the Trump White House. EPA-EFE/Samuel Corum

The sun sets on the Trump White House. EPA-EFE/Samuel Corum

When Donald Trump tested positive for COVID-19 on October 2 and was hospitalised a day later it was widely assumed this would put a major crimp in his re-election campaign. In the event, the US president recovered quite quickly and returned to the campaign trail with gusto after a typically bullish photo-op as he arrived back at the White House.

But survey evidence – initial findings from which are published here for the first time – shows that, despite having apparently triumphed over the virus, he did not escape the grasp of COVID-19 and that his handling of the pandemic played a crucial role in his defeat in the November 3 election.

COVID-19’s horrific toll on human life and its devastating effects on millions of people’s economic and psychological wellbeing have become omnipresent realities. So it’s hardly surprising that the University of Texas at Dallas’ national Cometrends survey, which was conducted in the two weeks before the presidential election, indicates that the pandemic was the dominant issue on many voters’ minds.

But survey evidence – initial findings from which are published here for the first time – shows that, despite having apparently triumphed over the virus, he did not escape the grasp of COVID-19 and that his handling of the pandemic played a crucial role in his defeat in the November 3 election.

COVID-19’s horrific toll on human life and its devastating effects on millions of people’s economic and psychological wellbeing have become omnipresent realities. So it’s hardly surprising that the University of Texas at Dallas’ national Cometrends survey, which was conducted in the two weeks before the presidential election, indicates that the pandemic was the dominant issue on many voters’ minds.

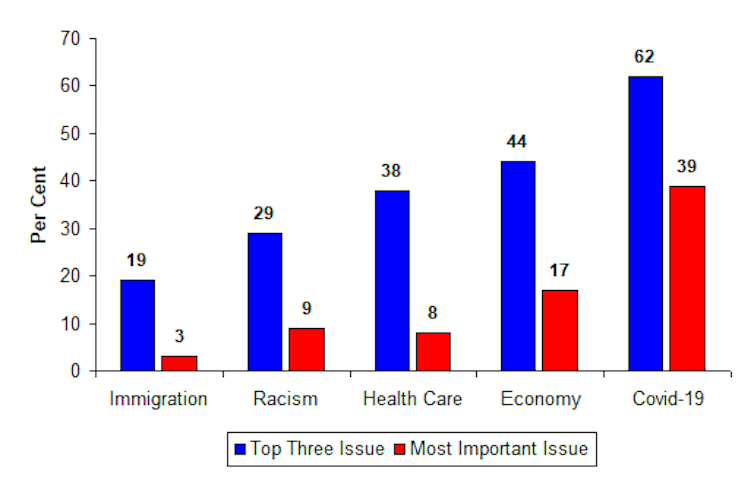

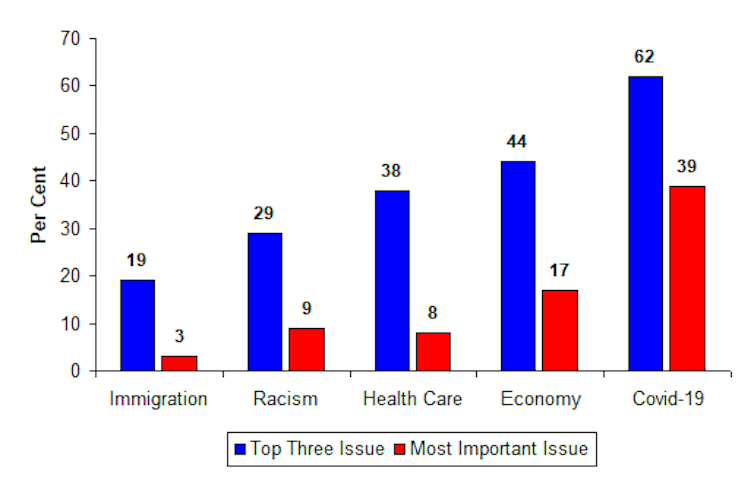

Graph 1: Important issues facing the country, October 2020.

Source: Cometrends October 2020 pre-election survey, Author provided

As the first graph, above, shows, 62% of 2,500 respondents cited the COVID crisis as one of the top three issues facing the country, while 39% said it was the single most important. No other issue – not even the ailing economy – was chosen as most important by one person in five.

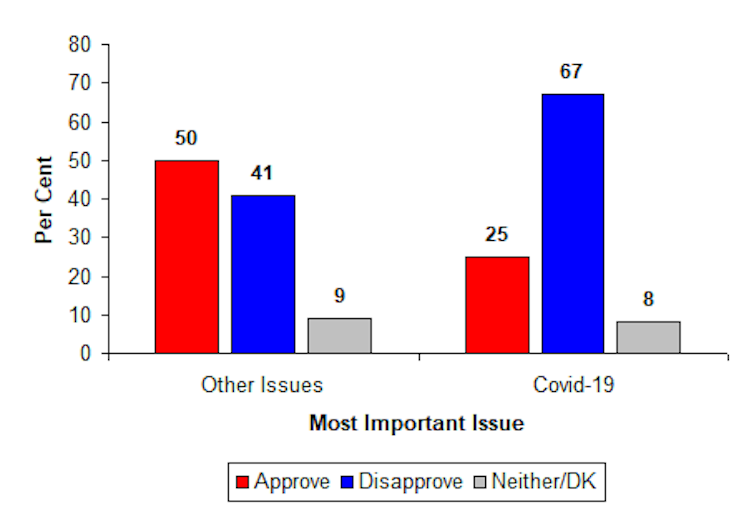

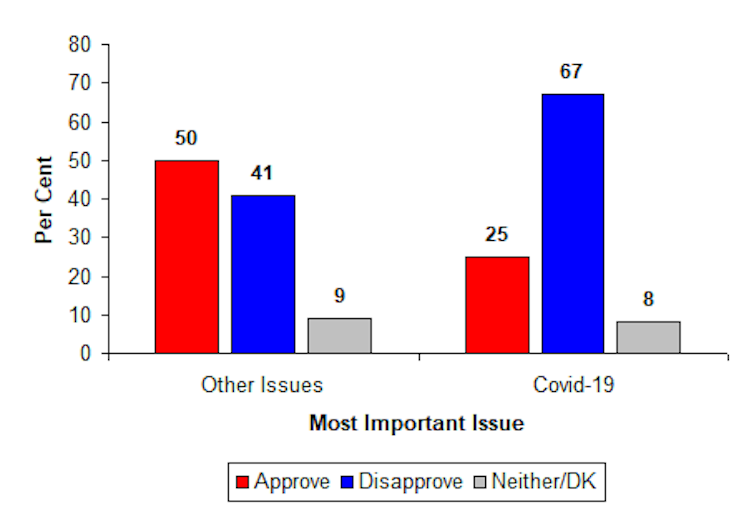

The salience of the pandemic as an issue was a major problem for Trump because an overwhelming number of voters judged that he had mishandled the crisis. As the second graph, below, shows, two-thirds of the Cometrends survey respondents said that they disapproved of the president’s response, while only one person in four approved. When given another chance to comment on his pandemic performance later in the survey, 51% said it had been “bad” or “terrible” and only 38% said “good” or “excellent”.

As the first graph, above, shows, 62% of 2,500 respondents cited the COVID crisis as one of the top three issues facing the country, while 39% said it was the single most important. No other issue – not even the ailing economy – was chosen as most important by one person in five.

The salience of the pandemic as an issue was a major problem for Trump because an overwhelming number of voters judged that he had mishandled the crisis. As the second graph, below, shows, two-thirds of the Cometrends survey respondents said that they disapproved of the president’s response, while only one person in four approved. When given another chance to comment on his pandemic performance later in the survey, 51% said it had been “bad” or “terrible” and only 38% said “good” or “excellent”.

Graph 2: Approval of Trump’s job performance on most important issue.

Source: Cometrends October 2020 pre-election survey, Author provided

These dismal ratings for the president on coronavirus were quite opposite to those for the economy – among people who thought the economy was the most important issue, 69% approved of the job the president was doing and only 25% disapproved. Although this was good news for Trump, only a relatively small minority (17%) of voters gave the economy top billing as their most important issue. Moreover, he could not rely on various other issues to improve his job approval rating – across all issues other than the pandemic, only 41% approved of the president’s performance compared with 50% who disapproved.

These dismal ratings for the president on coronavirus were quite opposite to those for the economy – among people who thought the economy was the most important issue, 69% approved of the job the president was doing and only 25% disapproved. Although this was good news for Trump, only a relatively small minority (17%) of voters gave the economy top billing as their most important issue. Moreover, he could not rely on various other issues to improve his job approval rating – across all issues other than the pandemic, only 41% approved of the president’s performance compared with 50% who disapproved.

Graph 3: Probability of voting for Trump by importance of COVID-19 issue. with statistical controls for other issues, partisanship, ideology and demographics.

Source: Cometrends October 2020 pre-election survey, Author provided

The third graph, above, shows clearly that if electors were not that concerned about the pandemic they were more likely to vote for Trump as president. But if they gave the issue the top priority they were much less likely to do so. The graph illustrates the impact of COVID-19 on voting for the president, while at the same time statistically taking into account a number of other factors that influence voting behaviour.

The latter include attitudes to the economy, the environment, healthcare, law and order and race relations, as well as other important measures such as identifications with the Democratic and Republican parties, liberal-conservative ideological views and socio-demographic characteristics. The probability of voting for Trump is only 42% among voters who thought COVID-19 was the most important issue but 53% among those who prioritised some other issue in the top three.

This pattern is the opposite for that of the economy. More than three-quarters of voters who gave top priority to the economy supported Trump. That number fell to less than one in three among those for whom economic conditions were not a major concern.

These numbers are nearly identical to those for the large group of potential swing voters who think of themselves as political independents and have no attachment to either of the parties. Independents giving top priority to the pandemic made up nearly 13% of the voters in the Cometrends survey and, other things being equal, the probability of them voting for Trump was very mediocre, at just slightly over 40%.

Game-changing virus

As he was preparing for the 2020 campaign, Trump repeatedly emphasised that his case for re-election was strengthened by his demonstrated ability to deliver economic prosperity. Soaring stock prices and record low unemployment numbers for many groups of voters including ethnic and racial minorities, women and young people were helping the president to make his case. Then the pandemic came along and profoundly changed America and the election-year issue agenda.

The third graph, above, shows clearly that if electors were not that concerned about the pandemic they were more likely to vote for Trump as president. But if they gave the issue the top priority they were much less likely to do so. The graph illustrates the impact of COVID-19 on voting for the president, while at the same time statistically taking into account a number of other factors that influence voting behaviour.

The latter include attitudes to the economy, the environment, healthcare, law and order and race relations, as well as other important measures such as identifications with the Democratic and Republican parties, liberal-conservative ideological views and socio-demographic characteristics. The probability of voting for Trump is only 42% among voters who thought COVID-19 was the most important issue but 53% among those who prioritised some other issue in the top three.

This pattern is the opposite for that of the economy. More than three-quarters of voters who gave top priority to the economy supported Trump. That number fell to less than one in three among those for whom economic conditions were not a major concern.

These numbers are nearly identical to those for the large group of potential swing voters who think of themselves as political independents and have no attachment to either of the parties. Independents giving top priority to the pandemic made up nearly 13% of the voters in the Cometrends survey and, other things being equal, the probability of them voting for Trump was very mediocre, at just slightly over 40%.

Game-changing virus

As he was preparing for the 2020 campaign, Trump repeatedly emphasised that his case for re-election was strengthened by his demonstrated ability to deliver economic prosperity. Soaring stock prices and record low unemployment numbers for many groups of voters including ethnic and racial minorities, women and young people were helping the president to make his case. Then the pandemic came along and profoundly changed America and the election-year issue agenda.

As the election date of November 3 approached, most people focusing on the economy as the number one priority continued to give Trump high marks. But these people were now a distinct minority of the electorate. COVID-19 had become the dominant issue for millions of Americans and our survey evidence strongly indicates that most of them judged Trump very harshly for how he was handling the crisis. In many cases, those adverse judgements translated into votes for Trump’s opponent, Joe Biden.

Trump may have recovered physically from COVID-19. But his prospects of re-election took a body blow that he would not recover from.

Authors

Paul Whiteley

Paul Whiteley

Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

Harold D Clarke

Harold D Clarke

Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas

Karl Ho

Karl Ho

Associate Professor of Instruction, University of Texas at Dallas

Marianne Stewart

Marianne Stewart

Professor of Political Science, University of Texas at Dallas

Disclosure statement

Paul Whiteley receives funding from the British Academy and the Economic and Social Research Council.

Harold D Clarke has received funding from the National Science Foundation (US).

Karl Ho receives funding from Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Taiwan Ministry of Education, Taiwan Fellowship.

Marianne Stewart receives funding from National Science Foundaton (US).

Partners

Trump may have recovered physically from COVID-19. But his prospects of re-election took a body blow that he would not recover from.

Authors

Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas

Associate Professor of Instruction, University of Texas at Dallas

Professor of Political Science, University of Texas at Dallas

Disclosure statement

Paul Whiteley receives funding from the British Academy and the Economic and Social Research Council.

Harold D Clarke has received funding from the National Science Foundation (US).

Karl Ho receives funding from Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Taiwan Ministry of Education, Taiwan Fellowship.

Marianne Stewart receives funding from National Science Foundaton (US).

Partners