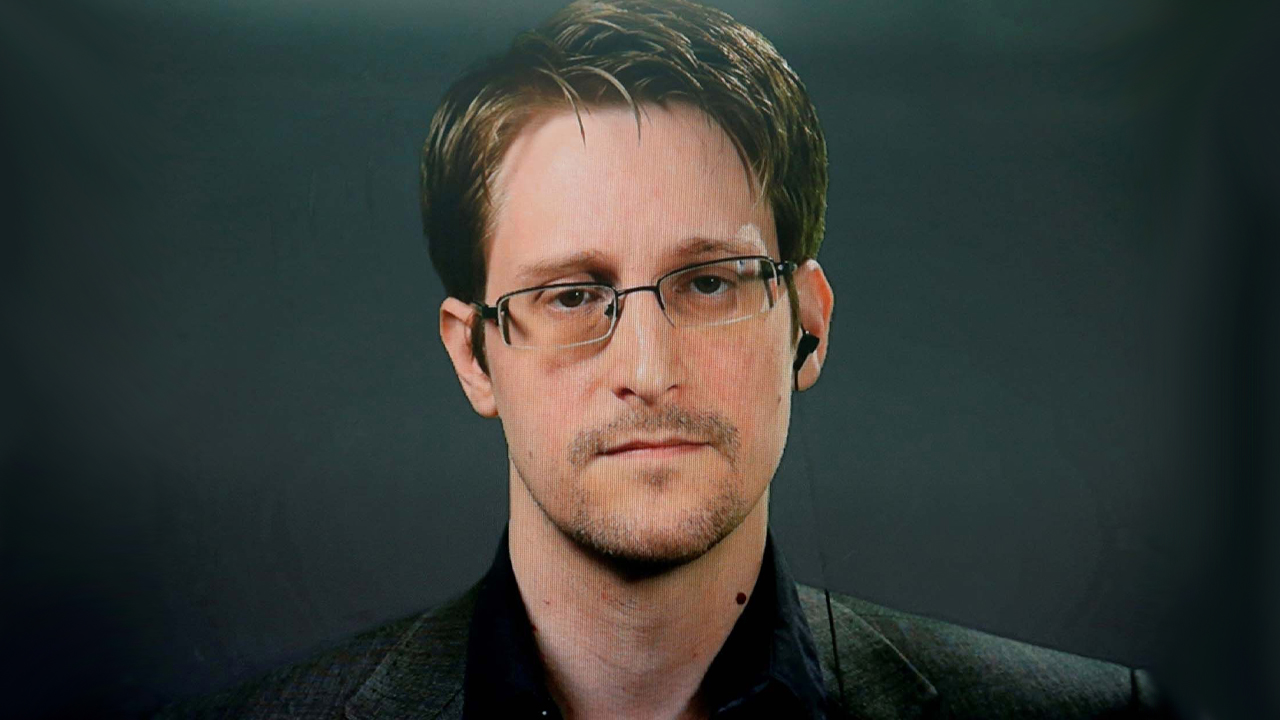

Just recently, the film producer and well known Youtuber, Naomi Brockwell, sat down with Edward Snowden and the two discussed a number of subjects including privacy and bitcoin. When Snowden talked about bitcoin, he delved into the protocol’s lack of progressive scaling and privacy. The famous whistleblower said that the biggest question he has is why are developers taking so long to resolve the issues cryptocurrencies have today.

The whistleblower and former NSA and CIA contractor, Edward Snowden is well known for his stance toward privacy and freedoms. Snowden recently had a conversation with Naomi Brockwell and he told her his thoughts about bitcoin (BTC), and digital currencies in general. At one point during the interview, Snowden said he was puzzled about the fact that developers have had years to scale bitcoin and add privacy, but have yet to produce any solutions.

Naomi Brockwell and Edward Snowden discuss bitcoin scaling and privacy.

When it comes to the transformation from our current monetary standpoint into the digital age, Snowden thinks digital currencies are “inevitable.”

“In fact, we’ve already seen states recognize that digital currency will be the next stage of money,” Snowden said to Brockwell. “They are trying to create competitors now effectively to bitcoin. I think they are not really hiding the fact. They are creating so-called central bank digital currencies which is just a rebranded version of fiat currencies. They don’t really have any desirable properties for the public at large beyond the government being able to more effectively disperse stimulus payments.”

Snowden added:

But that unfortunately means, and I don’t think a lot of people have the financial understanding to realize, that it actually means they are simply taxing you in a new way. Because a stimulus payment is a debasement of the currency at large.

Snowden further stated that cryptocurrency, in the general sense, does not solve the problem of inflation and hidden tax in that way. He added that the Bitcoin network, in a large way, makes it more predictable, as “it has a predictable rate of inflation which is constantly decreasing,” the whistleblower stressed.

“But the problem with everybody moving to digital currencies is that we know the Bitcoin network does not support throughput. Unfortunately, the Bitcoin network as it exists does not provide the privacy protections really necessary for these kinds of transactions,” Snowden added.

The privacy advocate insisted:

I think it should, and it could. It’s clear to me that the developers have realized this should be done— [Developers] haven’t actually moved to do this, which is puzzling to me because now they’ve had years to do it.

Snowden continued by adding that when he is discussing the subject of the inevitability of this transformation toward digital currency, he’s “not picking winners and losers.”

“I don’t have a horse, care, or concern, as to who wins this beyond [what] I think what the world needs is a truly independent means of enabling private transactions,” Snowden told Brockwell. “If that’s bitcoin, great— fabulous. I use bitcoin, I’ve used bitcoin before, I’ll continue to use bitcoin. But it’s very difficult for me to use bitcoin and yet that is a huge improvement to credit cards, which I cannot use because those networks are not even pseudonymous, in the way that a bitcoin transaction would be.”

Snowden concluded that the cryptocurrency community has some pretty well-understood flaws, but he doesn’t see any reason to say that they cannot be resolved. He can see that there are a lot of groups working on both offchain and onchain throughput. But at the end of the video, Snowden begged the question: “Why are you [developers] taking so long?”