While 20 Million Americans Lost Their Jobs In 2020, US Billionaires' Wealth Grew By $931 Billion

If you still need proof that the world is built for the wealthy to succeed, just take a look at how fortunes diverged this year.

Venessa WongBuzzFeed News Reporter

Posted on December 27, 2020,

BuzzFeed News; Getty Images

As millions of Americans end 2020 sick, jobless, hungry, indebted, or at risk of losing their homes, it’s unimaginable that at the other end of the spectrum, the wealthy, shielded from much of this misfortune, became even richer this cursed year.

But this is the reality of 2020. The same forces that made this year so awful for most people helped a select few add immense wealth.

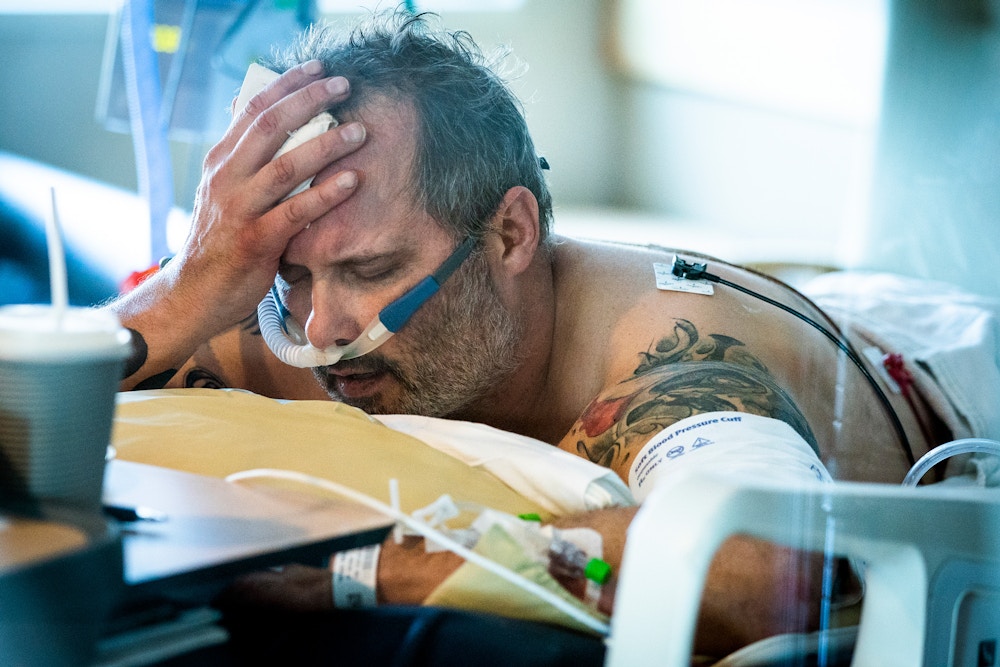

As more than 20 million people were receiving unemployment benefits and Congress held back too long on passing a second round of stimulus, American billionaires’ wealth had increased by $931 billion by the fall — more than the entire economy of the Netherlands. This divergence underscores just how drastically financial, political, and corporate systems are built to benefit those who already have so much, even in times of widespread loss, and exclude the have-nots. People with money, assets, and stocks saw their wealth and savings rise this year while those excluded from the year’s stock market rally were too often left in dire circumstances; some tech companies powered by low-paid contract labor thrived while their workers became sick or injured; and the widespread collapse of small businesses bolstered the success of competitors with greater access to resources and capital.

Meanwhile, existing economic structures almost ensure that the benefits of any financial recovery next year will continue to be spread unequally without some deliberate intervention. “Looking ahead to the next decade, investors face a world that is more indebted, more unequal,” according to a report by UBS. While top-line metrics about an improving economy will capture all the wealth held by the richest, it is important not to overlook the fallout experienced on the other side.

Consider, for example, who has benefited during the pandemic so far and who has lost.

Samuel Rigelhaupt / Sipa USA via Getty Images, Smith Collection / Getty Images

Left: Grubhub delivery bicycles in Manhattan. Right: a restaurant in California advertises its DoorDash delivery option.

It’s hard to imagine food delivery companies thriving when their partner businesses — restaurants — are hanging by a thread, but that is how things have shaken out.

Delivery services like Grubhub and DoorDash saw a huge jump in demand as shelter-in-place orders were issued around the country and restaurants were forced to close or limit indoor dining capacity. Small, local restaurants struggling to survive the pandemic turned to these services as a lifeline, despite unsustainably being charged high fees and commissions for orders placed through these platforms. Low-paid “gig workers” delivering for these companies were arrested and assaulted during the pandemic. “We have experienced strong growth in both new consumers and increased orders from existing consumers” during the pandemic, DoorDash stated in a company filing. The company is not profitable, but its revenue more than tripled during the first nine months of 2020 compared to the same period a year ago. This trend fueled DoorDash’s successful IPO this month, making billions for executives including CEO Tony Xu. DoorDash listed at $102 on Dec. 9 and ended the day with shares up 85%. As Wall Street enjoyed this windfall, 100,000 small businesses have closed so far.

A DoorDash spokesperson said, “Our three founders are also deciding how they want to personally give back to their communities and are each finding their own ways to do so.” She added the company has committed over $200 million to help restaurants and local communities.

Mandel Ngan / AFP via Getty Images Jeff Bezos

Amazon shareholders have been among the biggest beneficiaries of the pandemic as brick-and-mortar stores shut down; Amazon workers less so.

In the first nine months of the year, as local businesses around the country went out of business, Amazon’s profit increased by about 70% to $14.1 billion. “Prime members continue to shop with greater frequency and across more categories than before the pandemic began,” an Amazon executive told investors. The company’s rising stock price, which has nearly doubled since March, helped CEO Jeff Bezos’ net worth rise by $74 billion this year to nearly $190 billion. Meanwhile, about 20,000 Amazon employees have tested positive for COVID-19, and thousands of workers protested for higher pay, paid sick leave, and better protections during the pandemic.

The company has said it spent $750 million in additional pay for its front-line workforce, $500 million on a thank you bonus earlier this year, and established a $25 million relief fund for workers facing financial hardship or quarantine. Bezos has made donations this year as well, including $791 million to fight climate change, and $100 million to Feeding America.

Mykal Mceldowney / Reuters

The Tyson Fresh Meats plant in Logansport, Indiana.

Food companies continued to produce meat despite outbreaks of the coronavirus at their processing plants.

Tyson, for example, which makes chicken, beef, and pork, saw profits rise this last fiscal year to $2.15 billion while thousands of its workers tested positive for COVID. Tyson did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

View Press / Getty Images

A Walmart store in North Bergen, New Jersey.

Walmart’s revenue increased 6.5% to $407 billion from February to October compared to a year ago, with considerable growth in e-commerce, and its profit was up by about 45% — but many employees still lost their jobs.

The company laid off hundreds of corporate workers “in units including store planning, logistics, merchandising and real estate,” Bloomberg reported in July. Walmart also recently confirmed it will lay off 1,200 people in Arkansas and New Jersey in January as part of a reorganization. The company said it has hired 500,000 new associates since March across its stores and supply chain locations to meet demand. The company said in a statement that it has issued $2.8 billion in special bonuses this year, offered paid leave for workers affected by COVID-19, and increased the starting salary for some positions.

Andrew Harnik / AP Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel.

Some pharmaceutical companies developing COVID-19 vaccines have pledged not to profit from the pandemic (like Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca) — but not all.

Moderna struck a $1.5 billion deal with the US for 100 million doses of the vaccine, which it also developed with $955 million from the government, bringing the government’s total investment to $2.48 billion. Pfizer developed its vaccine without government funding and reached a nearly $4 billion deal for the purchase of 200 million doses. Both companies stand to make billions from the vaccine, which has drawn criticism. Stéphane Bancel, CEO of Massachusetts-based Moderna, gained $4.8 billion in wealth this year as the biotech company’s share price skyrocketed. Neither Moderna nor Pfizer responded to requests for comment.

Mike Blake / Reuters UnitedHealth Group offices in Santa Ana, California.

As people were not getting routine and elective medical care during the pandemic, insurers saw their profits rise.

For example, UnitedHealth, the country’s largest insurer by members, reported an increase in net earnings of 27% to $13.4 billion in the first nine months of the year. The company’s share price has increased dramatically since March. A spokesperson for UnitedHealth said, “We have taken a number of steps to support those we serve, our employees, their families, our communities and the broader health care system. You can find a summary of those actions here.” As insurers continued to pay out fewer claims for care while collecting premiums, some people also reported trouble getting their COVID-19 tests covered — during a pandemic. It’s possible the insurance heyday may draw to an end if the economy doesn’t improve, however, with United warning that rising unemployment could reduce revenue from employer-sponsored plans next year.

Tami Chappell / Reuters Equifax Inc. corporate offices in Atlanta, Georgia.

Credit bureaus — companies that gather data about you and determine your credit score for lenders — are also doing well as inequality widened during the pandemic, with the wealthy spending their money while others lost their jobs.

Consider Equifax: On one end, Equifax has benefited from the 2020 homebuying spree. The company offers specialized credit reports to mortgage lenders, and its US mortgage revenue from the summer was up by almost 90%, Equifax CEO told investors. On the other end of the spectrum, the company also offers employers services such as unemployment claims management. The rise in joblessness was a boon to the company — with so many people newly out of work, Equifax’s unemployment insurance claims business earned $50 million in revenue in the third quarter, up by over 70%, Equifax CEO told investors. The data Equifax gets about people from such employer services has been valuable to lenders this year too, as recent pay cuts and furloughs do not immediately impact a person’s credit score, but do impact their ability to borrow. “Data is valuable in all times. But during this COVID crisis, it's become increasingly valuable,” the CEO said at a conference. Equifax did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Jessica Mcgowan / Getty Images Sen. Kelly Loeffler.

The stock trades of wealthy politicians drew scrutiny this year when a number made transactions based on suspected access to privileged information.

The Justice Department did not pursue insider trading charges against Sens. Kelly Loeffler, James Inhofe, and Dianne Feinstein after its investigation did not find sufficient evidence that they had done anything illegal. The lawmakers all sold large amounts of stock, worth hundreds of thousands to millions, before the stock market crashed in the spring. Prolific trading by Sen. David Perdue has also raised eyebrows, as have trades by Sen. Richard Burr . As Fortune points out: “Although some suspicious trading activities have been widely condemned, the fact that no member of Congress has been prosecuted under the STOCK Act reveals the challenge in proving illegal insider trading by elected politicians. Those accused of such activity often claim that their transactions are based on public information or are managed by independent trusts. The difficulty arises from the lack of clarity in US securities law; indeed, years of legal practice in this area suggest that the boundaries of illegal insider trading are difficult to define. The fact is that the law ultimately fails to deter members of Congress from allegedly engaging in such activities.” All of the politicians deny any wrongdoing.

Amr Alfiky / Reuters JP Morgan Chase Bank in Manhattan.

And while Congress sat on its hands instead of passing a second round of stimulus, the government paid banks billions of dollars in fees for processing PPP loans to businesses that were impacted by the pandemic.

Banks say the cost of handling PPP loans will wipe out any potential profit from the fees they’re receiving, and Bank of America, JPMorgan, Citibank, and Wells Fargo pledged not to profit from the program, the New York Times reported. While banks have laid off thousands of workers this year, overall they have remained profitable despite ongoing economic uncertainty that may affect banking customers’ ability to repay loans. They continued to pay dividends to investors and will also be able to resume stock buybacks soon, which have been criticized for enriching “shareholders, generally wealthier Americans, at the expense of workers, new plants and research, and broader economic development,” according to the Wall Street Journal. Sen. Elizabeth Warren in October said these payouts would deplete banks’ “capital buffers at a time when they should be preserving them to support lending to households and small businesses.”

A spokesperson for JPMorgan said the company has “delayed payments and refunded fees for customers on over 2 million accounts,” provided $50 million in philanthropic support, helped “business clients secure more than $45 billion in new credit and $950mm in new loans for small businesses,” helped “corporate clients raise hundreds of billions in capital,” among other efforts.

Citi said in a statement, “Throughout this crisis, we have continuously supported our customers, clients and communities while maintaining strong capital and liquidity positions.”

These are just a few of the organizations that made money during the pandemic — and as the financial crisis continues to affect millions of people across the country, 2021 is looking set to be another banner year for inequality in America.

Venessa Wong is a reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

© Getty Images Farmers resist reforms designed to destroy livelihoods

© Getty Images Farmers resist reforms designed to destroy livelihoods