This article, originally published on January 23 2017,

has been updated to reflect ongoing developments

in US-Cuba relations.

Last Friday, speaking in Miami’s Little Havana neighbourhood, president Donald Trump announced a change of American policy toward Cuba, which under the administration of Barack Obama had seen significant rapprochement with the US.

“Effective immediately, I am cancelling the last administration’s completely one-sided deal with Cuba,” he said.

Rhetoric aside, the policy Trump outlined doesn’t fundamentally alter many of his predecessor’s steps toward normalisation, including renewed diplomatic relations, unlimited visits for Cuban Americans visiting family back home and the end of the US immigration policy that had favoured Cubans.

And though the speech has the government and small businesses in Cuba on edge, no single Trump decree is likely stop the changes that have already swept the island over the past decade.

The post-Fidel area began ten years ago

Ever since Fidel Castro died in November 2016, foreign observers – journalists, political tourists, and the like – have been flocking to the streets of Havana. Let’s go and see communist Cuba before it is too late! they reason.

What this reaction misses is that Cuba has already changed: the post-Fidel era is already over a decade old.

My research, published in January 2017 in the Mexican Law Review, shows major shifts in the governing style and ideology of the country. The charismatic leadership that epitomised Fidel’s time in power is gone, replaced by a collective arrangement. And Cuba’s centrally planned economy has integrated market socialist features.

These changes will likely be accelerated by Barack Obama’s repeal of the US policy that gave Cuban migrants favoured immigration status – both by eliminating an escape route for dissatisfied citizens and by reducing potential future remittances. Trump does not plan to undo this change.

The end of charismatic leadership

When Fidel fell gravely ill in July 2006, he provisionally delegated his dual posts – president of the Council of State and first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba – to his younger brother Raúl, long-time head of the Revolutionary Armed Forces and second secretary of the Communist Party. As Fidel’s health further deteriorated, the National Assembly made Raúl president in February 2008.

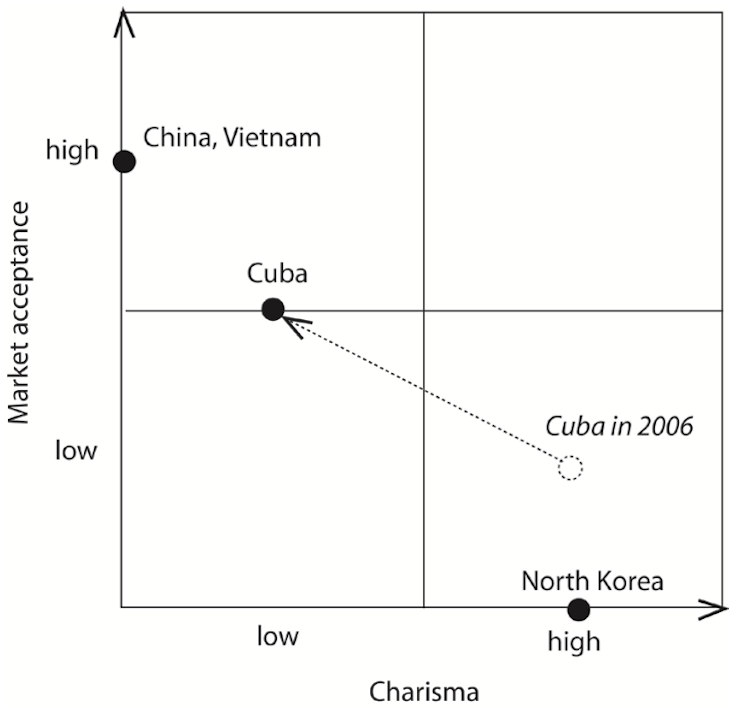

This move kept succession within the family, but Raúl has rejected any Kim dynasty-style future for the country. If ten years ago Cuba looked more like North Korea than China, today the opposite is true.

Breaking with Fidel’s decades-old practice, Raúl recommended to the delegates of the sixth Party Congress in April 2011 that they limit public officials to a maximum of two five-year terms; this soon became the official Party line.

In the short term, term limits meant that Raúl Castro’s presidency would end in February 2018, which he has confirmed. In the long term, that raised questions on the post-Castro era. To be sure, in 2013 Miguel Díaz-Canel, a Communist Party insider, was promoted to first vice president of the Council of State – the first time ever that a revolutionary veteran did not hold that position. Technically, according to the Cuban constitution, if the president dies, the first vice-president takes over.

The seventh Party Congress, held in April 2016, nonetheless appointed Raúl Castro to be first secretary. While this does keep a revolutionary veteran in control of a key post after 2018, for the first time the head of the Cuba’s Communist Party will not be the same person as Cuba’s president.

The rise of market socialism

Market socialism can be defined as “an attempt to reconcile the advantages of the market as a system of exchange with social ownership of the means of production.”

As if following this definition from the Oxford Dictionary of Social Sciences, the sixth Party Congress approved that from now on “planning will take the market into account, influencing upon it and considering its characteristics.”

This is a clumsy engagement with the market, treating it as an alien from outer space. And it epitomises the current ideological hardships of the Cuban regime.

Still, Raúl Castro has overseen the largest expansion of non-state socioeconomic activity in socialist Cuba’s 50-year history.

Cuba’s National Office of Statistics reports that in 2015 71% of Cuban workers were state employees, down from 80% in 2007, and the number of (mostly urban) self-employed workers has grown from 141,600 in 2008 to half a million in 2015. In a country with a total workforce of five million, this is not a trivial change.

From 2008 to 2014, more than 1.58 million hectares of idle land has been transferred into private hands. That’s nearly a quarter of Cuba’s 6.2 million hectares of agricultural land, roughly on par with state-owned land (30%)

In sum, the market is no longer the enemy, it’s a junior partner in Cuban central planning. The last Party Congress, Cuba’s seventh, approved the continuity of controlled liberalisation efforts by turning market socialism into Communist Party doctrine, stating that “the State recognises and integrates the market into the functioning of the system of planned direction of the economy.”

The new Cuban polity

The rise of market-socialist ideology emerged, to a substantial extent, from the decline of charismatic authority.

Cuba’s next generation of leaders –- expected to take over in 2018 -– will not enjoy the same unquestionable legitimacy as its founding fathers, much less that of Fidel Castro. So the inevitable passing of the revolutionaries still in power today, most of whom are in their 80s, makes the already difficult process of revamping the regime even tougher.

Raúl Castro’s challenge over the past decade has thus been not only to make his presidency stand on solid ground, but also to make sure that such a ground endures after he leaves. The question of economic performance was clearly central to that task.

Raúl saw market socialism as a way to strengthen Cuba’s economy without abandoning its Castro-era ideals. The revolutionary veterans’ interest in seeing the system they built survive is unsurprising, and it explains their rejection of any capitalist encroachments.

But it remains to be seen how long – and if – this ideological limit will survive them.

Let’s return to the earlier chart presenting a comparison of surviving Communist countries at present. It shows Cuba today, after ten years of Raúl, located somewhere in between North Korea (where an orthodox Soviet-style economy is still firmly entrenched) and countries such as China and Vietnam that have seen capitalism restored, and somewhat closer to the latter.

But the difference between “medium” market acceptance and “high” market acceptance is a substantial one. The latter presupposes a comeback of the bourgeoisie – the social class of owners of the means of production, expropriated by Castro’s revolution – and thus far this key ideological limit remains strong in Cuba.

Since the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, many have assumed that the fall of communist Cuba is a matter of when not if. Only by abandoning the focus on “the fall” and understanding how communist rule has survived in Cuba we can grasp how mightily Cuba has already changed.

Postdoctoral fellow, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM)

Disclosure statement

Ramón I. Centeno received funding for his doctoral studies –that produced this research– from Mexico's National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt, for its acronym in Spanish). He also received financial support for two field trips to Cuba from the Department of Politics of the University of Sheffield, and the Society of Latin American Studies (SLAS). He has an editorial role in the Mexican political magazine 30-30.com.mx.