Bloomberg News | November 29, 2021

Hail Creek mine is located 120 km southwest of Mackay in central Queensland and supplies international markets with hard coking and thermal coal.

Just inland of Australia’s east coast, roughly 200 miles from the Great Barrier Reef, a single coal mine run by Glencore Plc emitted so much super-warming methane in a year that it had the same climate warming impact as the annual pollution from more than 4 million U.S. cars.

The Hail Creek coal mine leaked an estimated 230,000 tons of methane a year in 2018 and 2019, according to researchers with SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, who analyzed satellite data from the European Space Agency. Because methane traps over 80 times more heat than carbon dioxide in its first two decades in the atmosphere, the mine had the same short-term warming impact as roughly 19 million tons of CO₂ a year.

The report is one of the first efforts by researchers to quantify just how much methane is coming from individual mines in Australia. Coal itself produces the most CO₂ emissions out of all fossil fuels and nearly 200 countries have agreed on the need to reduce its use to avoid the worst effects of climate change. The new study shows that there’s an added danger: disastrous amounts of methane emitted during the mining process.

The Hail Creek mine is among a handful of coal operations in Australia’s Bowen Basin identified by the researchers as super-emitters, including mines run by BHP Group and Anglo American Plc. Hail Creek, which Glencore took over from Rio Tinto Group in August 2018, was the biggest offender. It accounts for 20% of Australia’s methane emissions from coal mining even though it produces just 1% of the nation’s coal output, according to the report, published Monday in the Environmental Science & Technology journal.

The researchers grouped five other mines in the Bowen Basin into two clusters because it was difficult to distinguish their individual contributions due to their close proximity. Broadmeadow, owned jointly by BHP and Mitsubishi Corp., and Anglo’s Moranbah North and Grosvenor mines released 190,000 tons of methane annually in 2018 and 2019, according to the report. Glencore’s Oaky North and Anglo’s Grasstree mines emitted an estimated 150,000 tons of methane a year.

Glencore said its Bowen Basin coal business reports emissions in line with Australia’s requirements. Anglo American said it submits methane emissions annually, by location, to the country’s clean energy regulator and also makes disclosures at a business level in its annual report. A spokesperson for BMA, BHP’s joint-venture with Mitsubishi, said the company publishes emissions from its Australian operations in accordance with the country’s standards.

None of the operators said how much methane comes from the individual mines identified by the Dutch researchers. BHP spokesman Ben Dillaway told Bloomberg in July its Broadmeadow and Goonyella Riverside mines cumulatively emit an average of about 32,000 tons of methane a year.

The new analysis underscores just how big a problem coal is for Australia, which lags other developed nations in tackling climate change. Although it’s extremely vulnerable to the impacts of rising temperatures, Australia was among the last advanced economies to set a target to zero out emissions, has been criticized over the credibility of its plan, and refused to join a global pledge to reduce methane emissions 30% by 2030.

The findings suggest there may be “a large underreporting of methane emissions in the national inventory,” authors including Pankaj Sadavarte and Ilse Aben wrote. They speculated that the outsize releases from Hail Creek could have come from surface mining operations and efforts to drain gas when expanding the facility.

The research underscores the wide range of climate impacts from different mines. According to the International Energy Agency, the world’s dirtiest coal emits as much as 100 times more methane than cleaner operations. Most of the methane reductions from coal should come from a “drastic fall” in its use, the IEA said in an October report, though steps to minimize leaks “need to happen in parallel.”

The Dutch researchers estimated that all six mines spewed a combined 570,000 tons of methane a year over the study period, accounting for roughly 55% of the reported methane emissions from coal mining in Australia — despite only contributing about 7% of the nation’s production.

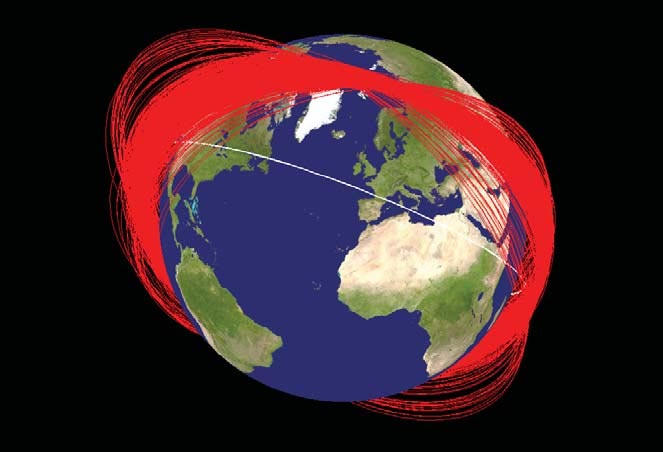

Australia’s Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources said in a March report that it’s “premature to use satellite data to quantify emissions from methane sources.’’ The Dutch scientists used observations from the ESA’s Sentinel-5P satellite to estimate daily methane flux rates from the mines and compared those with emissions from global inventories and figures used in Australia’s reports to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The main caveat with this approach is that the Sentinel-5P “is designed for quantifying methane over large regions rather than precise attribution to individual facilities,” said Riley Duren, chief executive officer of Carbon Mapper. The nonprofit has received funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies.

But Duren said that the findings — that just a handful of mines appear to be responsible for a disproportionate amount of emissions — broadly align with what his team has found studying U.S. coal mines in southwest Pennsylvania using instruments with much higher spatial resolution. Just four underground mines in that region appear to be responsible for 22% of total U.S. methane emissions from underground mines, or about 300,000 tons.

The Dutch research is also similar to another analysis by Kayrros SAS. The French geoanalytics firm found earlier this year that for every ton of coal produced in the Bowen Basin, an average of 7.5 kilograms of methane is released. That was 47% higher than the average global methane intensity estimated by the IEA, according to Kayrros.

Geologically older and deeper coal deposits tend to contain more methane than shallower seams, according to the IEA, which is why emissions from surface mines such as Hail Creek tend to be lower than underground mines. But it’s harder to mitigate leaks from open pit reserves, where emissions are often spread over larger areas and more diffuse.

Ilse Aben, one of the Dutch researchers, said they were surprised by the large methane emissions coming from Hail Creek. “I hope getting attention for this forces people to explain what is happening there,” said Aben. “It requires an explanation.”

(By Aaron Clark, with assistance from Anjali Cordeiro and Jane Pong)