The students are striking over better pay, healthcare and third-party arbitration for harassment and discrimination complaints

Michael Sainato

Thu 9 Dec 2021

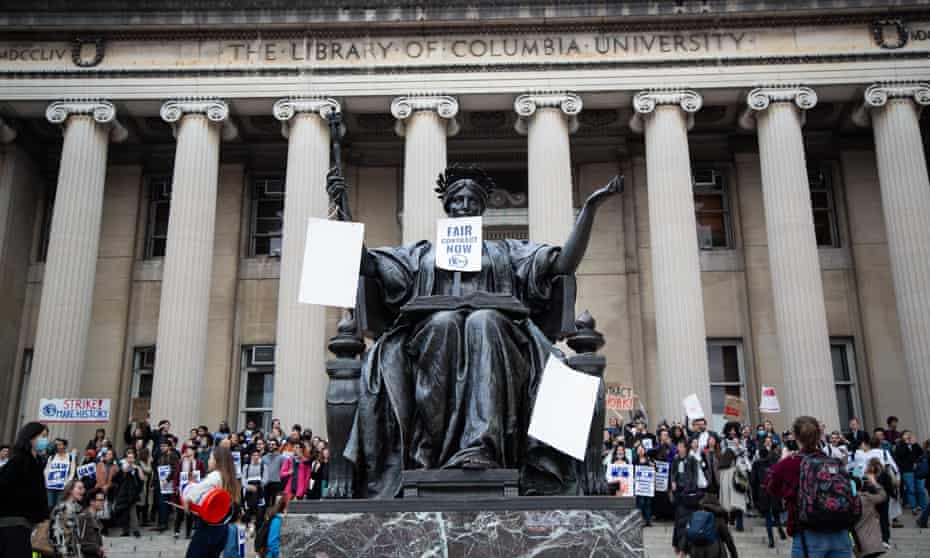

About 3,000 graduate workers at Columbia University in New York City, who have been on strike since 3 November, recently received an email from the university human resources department threatening the workers with replacement if they continue striking.

The strike is the largest active strike in the US.

US school bus drivers in nationwide strikes over poor pay and Covid risk

The email, sent on 2 December by Columbia University human resources vice-president Dave Driscoll, informed workers their positions would be replaced if they continue striking past 10 December.

“Our interpretation of this email is that it’s basically a threat. They are saying here’s the date, December 10. If you’re still exercising your right to engage in protected activity on or after December 10 there’s no guarantee that you’re going to get your job back. So we think that’s the intention of the threat, but we also think that what they’re doing is unlawful,” said Ethan Jacobs, a graduate student worker in the philosophy department at Columbia University and a member of the GWC-UAW Local 2110 bargaining committee.

Jacobs described the unfair labor practice charges filed by the union against the university with the National Labor Relations Board. They include the university enacting a wage freeze and changing wage disbursement schedules earlier this year without negotiating with the union after its members rejected a tentative agreement after a strike in the 2021 spring semester.

According to the National Labor Relations Act, workers who strike to protest unfair labor practices cannot be discharged or permanently replaced. Jacobs expressed the union’s intent to file additional charges with the NLRB over the university’s threat to replace workers on strike.

Graduate workers have been on strike over improved compensation to cover the high cost of living in New York City, a third-party arbitration process for harassment and discrimination complaints and improved healthcare plans for student workers, including dental care and vision coverage.

“Columbia University operates like these early 20th century company towns. For example, I live in an apartment that is owned by Columbia, so the university is also my landlord. They are the source of my health insurance, the source of my job, the source of my academic progress. In nearly every aspect of my life, Columbia has some sort of say in how that goes and that’s really problematic,” added Jacobs.

Over the past several years, graduate student workers at Columbia University have fought for a first union contract with the university, after securing a ruling by the NLRB in 2016 that affirmed graduate students are employees with the right to unionize.

Workers are pushing for a wage floor of $45,000 annually for first-year doctoral students on one-year appointments and a minimum hourly wage of $26 for hourly workers. Current wages vary by department from as low as $29,000 annually for student workers at the School of Social Work to $41,500 for engineering student workers. The hourly minimum wage at the school is $15.

“The pay structure we have now is the subject of our second unfair labor practice charge. We used to get paid in a lump sum at the beginning of the semester. Our pay was never enough to begin with, but people could budget around it,” said Jonathan Ben-Menachem, a graduate student worker in the Department of Sociology, who noted student workers have been forced to sign an attestation form that they were not striking in order to receive pay during the strike.

Columbia University received returns on their endowment of 32.3% in fiscal year 2021, increasing the school’s endowment value to $14.35bn and ending the fiscal year with a $150m operating surplus, recovering from initial financial losses incurred by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Tamara Hache, a graduate student worker in the Latin American and Iberian cultures department and an international student, expressed concerns over the threat of replacement and its impact on the university as a whole, including international students who cannot work outside the university.

“This measure the university is trying to carry out, of this threat, would be incredibly destructive for everyone at the university. It wouldn’t just affect us as graduate student workers, but everyone. The quality of our students’ education and our departments would be terribly impacted,” said Hache.

In response to the threat of replacement, the union is rallying support from undergraduate students, parents, alumni, faculty and the public, and have held protests.

Columbia University said in a statement, “In the face of enormously trying circumstances created by the strike, our first priority is the academic progress of our students, particularly undergraduates whose classes are being disrupted. The message sent last week to the union bargaining committee explaining the university’s approach to spring appointments and teaching assignments was necessary to fulfill that commitment. Replacing instructors who leave the classroom is permitted by US labor law. With respect to striking student workers who return to work after December 10, we will make every effort to provide them with suitable positions, as available.”

After administrators sent an email saying that students who remained on strike after Friday were not guaranteed jobs next term, union members turned up the heat.

By Ashley Wong

Published Dec. 8, 2021

Student workers on strike at Columbia formed picket lines that blocked off entrances to campus and prevented other students from getting to class. A giant inflatable fat cat waved in the breeze as dozens of drivers heading down Broadway honked their car horns in support. A 10-foot-banner reading “Fair Contract Now” was unfurled along an overpass on Amsterdam Avenue.

The scenes of protest dotting the campus on Wednesday came six weeks into a strike by the Student Workers of Columbia, a United Auto Workers Local 2110 union with about 3,000 graduate and undergraduate students. The strike, which is being waged over higher pay, expanded health care and greater protections against harassment and discrimination, has embroiled the campus administration in a lengthy struggle with its own student body.

Wednesday’s action brought one of the largest turnouts since the strike began, as union members were joined by members of student worker unions and faculty from New York University, Fordham University and the City University of New York, and labor unions such as Teamsters Local 804.

“Today, I think, there’s a real show that we are the backbone of this university, and without us, the university doesn’t really function,” said Mandi Spishak-Thomas, a doctoral student at the School of Social Work and a member of the union’s bargaining committee.

The picket line came days after Dan Driscoll, the vice president of the university’s human resources department, sent an email to student workers saying that those who did not return to work by Friday were not guaranteed jobs next semester.

“Please note that striking student officers who return to work after December 10, 2021, will be appointed/assigned to suitable positions if available,” Mr. Driscoll said in the email.

The widely circulated email sparked outrage and accusations that the university was attempting to retaliate against strikers.

Scott Schell, a university spokesman, argued that its actions did not qualify as unfair labor practice. He cited the National Labor Relations Act, which says that while firing workers for going on strike is illegal and workers are entitled to get their jobs back after a strike ends, employers are allowed to replace those workers while the strike continues.

“In the face of enormously trying circumstances created by the strike, our first priority is the academic progress of our students, particularly undergraduates whose classes are being disrupted,” Mr. Schell said. “The message sent to explain spring appointments and teaching assignments was necessary to fulfill that commitment.”

Wilma B. Liebman, a former chairwoman of the National Labor Relations Board, said the university seemed to be putting undue pressure on student workers by implying they were guaranteed to keep their jobs only if they were to quit striking now.

“To me, it’s a way of creating fear and doubt and coercing them, essentially, because of that fear and doubt, to abandon the strike,” Ms. Liebman said.

Columbia’s student workers were joined in Wednesday’s picket line by union members and faculty from other universities.

Several faculty members participating in Wednesday’s picket line said that the email had motivated them to join the union’s efforts. About 100 faculty members held their own protest on campus on Monday.

“That’s part of what I think is driving more faculty to come out,” said Susan Witte, a professor at the School of Social Work. “It was retaliatory, it was inappropriate and it was hugely disturbing.”

Sign up for the New York Today Newsletter Each morning, get the latest on New York businesses, arts, sports, dining, style and more. Get it sent to your inbox.

Ms. Witte added: “As a tenured faculty member, I think that protected employees have a responsibility to speak out on behalf of other employees.”

Local politicians such as Zohran Mamdani, a state assemblyman who represents parts of Queens, also showed up to support picketing union members. Mr. Mamdani said he had gotten messages almost daily from constituents who are graduate students at Columbia.

“These workers are putting everything they have on the line,” he said. “The fact that students are willing to forgo thousands of dollars in wages, the prospect of their future professional opportunities — it speaks to just how dire the situation is.”

In a joint letter to Lee C. Bollinger, the university’s president, Representatives Adriano Espaillat, Jerrold Nadler and Grace Meng, all New York Democrats, called on the university to bargain with union members in good faith. They also emphasized the importance of student workers for the university’s elite reputation and stability.

“As we work to recover from a global pandemic, it is vital that these lengthy negotiations conclude and yield a fair agreement,” they wrote.

Students said the strike had affected undergraduate core courses, particularly larger introductory ones that rely on graduate instructors for grading.

They said they were exasperated and nervous about getting incomplete grades, but they directed most of their irritation at the university.

Izel Pineda, a sophomore at Barnard College majoring in neuroscience, said she felt the university had not offered enough guidance on what would happen to undergraduates whose graduate instructors were striking.

She said she and her friends felt that the university was trying to use undergraduates’ frustration to pressure the union to end the strike, citing a campuswide email this week that linked to an anonymous opinion piece in the Columbia Daily Spectator, written by an undergraduate critical of the strike.

“Columbia has been leaving undergrads out to fend for themselves and mitigate the relationship between the strike and the undergrad class,” Ms. Pineda said.

Julia Hoyer, a Barnard sophomore majoring in history, said the conflict had marred the return to in-person learning.

“It’s been a hard adjustment to begin with,” she said. “But then, with the threat of incompletes because Columbia won’t pay their graduate students a living wage, it’s just unfair to everybody involved.”

The university and the union have been bargaining through a federal mediator for about two weeks. With the end of the semester rapidly approaching, both expressed eagerness to settle on a contract.

“We’re committed to working as hard as we can to reach a fair and equitable agreement as soon as possible to end the disruption to undergraduate studies and campus activity,” Mr. Schell said. “We welcome the union’s willingness to work towards a compromise.”

The union, for its part, proposed a new contract Tuesday that members said contained significant concessions.

“We do want a contract as quick as possible, but we need one that actually gives us the reasonable package that our union has been fighting for,” said Jackson Miller, a doctoral student in material science and a member of the union’s bargaining committee. “We’ll continue to fight until our demands are met.”

Correction: Dec. 9, 2021

An earlier version of this article misidentified one of the unions whose members joined the picket line. It was Teamsters Local 804, not 104.

A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 9, 2021, Section A, Page 27 of the New York edition with the headline: Strikers Fear Retaliation From Columbia.