An undying interest in vampires

- Philip Cox

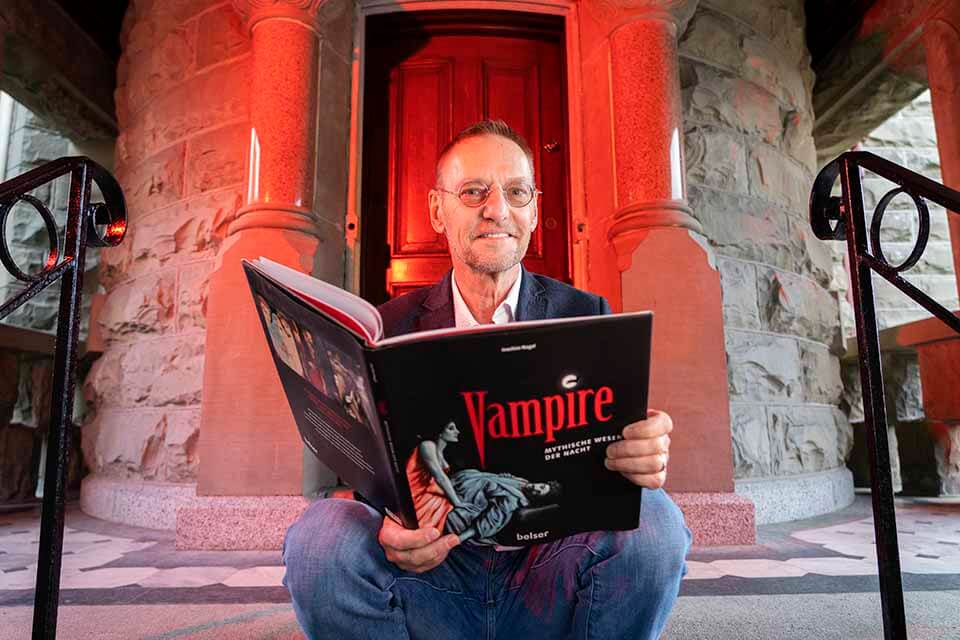

Although Halloween comes but once per year, the thirst for stories about vampires never seems to die. This has helped one UVic humanities professor, Peter Golz, to pursue his own passion for the study of these stories in film and literature for more than 20 years. In doing so, he’s made Victoria home to one of North America’s most popular university courses on vampires.

“The figure of the vampire allows students to delve into the desires and fears of particular cultures in particular historical moments,” says Humanities Associate Dean Academic Lisa Surridge. “Peter Golz has created a master class in cultural studies that has stood the test of time.”

More than a librarian of lore

For anyone who has spoken with Golz, it’s not surprising that his office is filled with an impressive range of vampire-related paraphernalia — action figures from popular TV shows like Twilight and Buffy: the Vampire Slayer; a vampire-themed magnetic poetry kit; a Dracula lunch box; a bottle of Dracula-branded wine (red, of course); a ‘little vampire pacifier,’ replete with blood-tipped fangs, still in its original packaging; along with film posters, DVDs and endless rows of books, books, books.

Even backed by this impressive cavern of keepsakes, the breadth and depth of Golz’ knowledge of vampire films, literature, culture and history is endlessly enthralling.

The briefest of conversations with this humble professor about his passion for the subject feels like an immersive symposium in vampirology. And no wonder: Golz has been teaching one of North America’s most popular courses on vampires for 20 years this fall.

A curriculum of vampires

The course Golz created for UVic’s Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies in 2001, which he’s taught every year since—A Cultural History of Vampires in Literature and Film—has captured the imagination of students, fans and the media alike over the last two decades.

It has been featured by a wide range of national and regional news outlets such as the Globe & Mail, CBC, Times Colonist and CHEK, and appears on countless ‘best course’ lists and vampire fan sites.

In 2014, Warner Brothers approached Golz about including a short clip on the course in the bonus materials of a special 20th anniversary edition BluRay release of the now-classic film Interview with the Vampire, but the deadline for filming was two weeks before the course started that year.

Attention like this, alongside glowing reviews from students, has helped course enrolment swell from 75 students in its first year to over 300 at its peak. When offered online for the first time last year as a result of the pandemic, the course attracted students from across Asia and Europe, as well as North and South America, despite the extreme time differences. Some passions never seem to sleep.

A vampire for every generation

In addition to the media attention and buzz generated on campus by word of mouth, Golz attributes the success of his course in part to the subject matter itself.

“Vampires have become a lot more interesting in the last 20 years, because they are not depicted as the stereotypical Other as they once were,” he says. In line with their famed shapeshifting powers, Vampires have learned to adapt—and fit in. “Now vampires are more likely to live among us, like in the TV series True Blood, the Twilight films or Buffy: the Vampire Slayer. And we are more likely to hear them tell their own story, like in Interview with the Vampire, which makes them more sympathetic characters.”

There is also an ever-growing diversity in the types of vampires, such as the child vampire of 1975’s Salem’s Lot, the ‘psychic vampire’ of Lifeforce and the ‘olfactory vampire’ of Perfume: The Story of a Murderer.

The characteristics of our imagined vampires shift alongside our times and circumstances. For instance, there’s a growing demand for ‘pandemic vampires,’ Golz says, as seen in films like 2007’s I Am Legend and in TV series like The Strain.

Although this trend clearly speaks to our own time, the concept behind it has a long history. In the classic 1922 German Expressionist silent horror film, Nosferatu, death follows the vampire protagonist Count Orlok indiscriminately when he moves from Transylvania to Germany. The doctors in his town blame these deaths on an unspecified plague brought in by a swarm of rats that arrive with Orlok’s ship.

“Nosferatu was filmed in 1921, just after the Spanish flu epidemic,” Golz explains, “but it was set in the 1830s when there was a big cholera outbreak in Germany, rather than in its present day or in the late 1800s when the novel upon which it was based [Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula] was set. I think the film’s director wanted to make something that was really appropriate for its time, which is a concern we often see reflected in vampire storylines.”

This continual evolution of vampire mythology has helped to keep both vampire stories and Golz’ course content fresh over the decades.

The future of the darkness seems bright

Given the course’s longevity and sustained popularity, it’s hard to believe that it took Golz eight long years to develop and get it approved by university administrators.

“Some of my colleagues were very much against this course, which is part of the reason I had to have “literature” in the course title — it had to have a literary component to give it credibility,” Golz recalls. “Now there are a lot of courses throughout Canada and the US that focus on vampires, zombies and other fantasy- and horror-based works. It has become a very popular topic with a very bright future.”

When asked about the brightest moments in his own career, Golz can list many: that time when Ballet Victoria invited him to introduce their new Dracula ballet and to bring his entire class to one of their performances, or the half-dozen presentations by leading vampire scholars that Golz has brought to UVic as part of the Lansdowne Lecture series, or the novel ideas of students who have sat in his classroom and shared with him their own passion for the shadowy underworld of the undead.

“This course is a lot of fun for me and I get to work with students who are really interested in the topic and do great work, so as long as I’m here I will continue to teach this course,” Golz states.

“But, I am obviously not a vampire, so it has to end at some point. But, maybe then it will be reborn. Who knows?”