Bloomberg News | May 22, 2022

(Reference image by Bautsch, Wikimedia Commons).

Trying to attach a million-dollar, 60-ton wind turbine blade to its base is challenging in any circumstance — getting the angle wrong by even a fraction of a degree could affect the machine’s ability to generate power. Now imagine trying to do it in the middle of the North Sea, one of the world’s windiest spots, with waves swelling around you. It’s like tying a thread to a kite at the beach and then trying to put it through the eye of a needle.

That’s the challenge confronting Western leaders who want to wean their economies off Russian fossil fuels. Building more offshore wind is one of the more efficient ways for some countries to replace that dirty energy. Turbines built at sea benefit from stronger and more consistent wind speeds. They also avoid one of the biggest hurdles to constructing a wind farm: neighbours who don’t want windmills ruining their view.

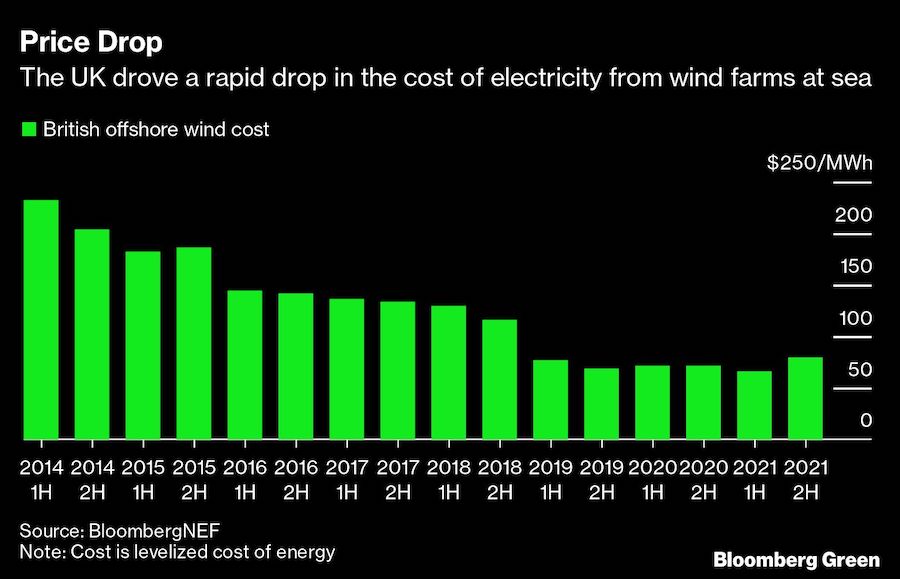

The UK in particular has supported the industry by allocating vast tracts of seabed to developers and doling out generous subsidies, helping improve the technology and lower costs. Since the first British project was completed in 2000, turbines have become more than five times as powerful and the price of wind-generated electricity has fallen below power from fossil fuel or nuclear plants. By the end of the decade, Prime Minister Boris Johnson aims to boost the UK’s offshore wind capacity to 50 gigawatts, more than triple the current fleet.

Achieving that goal will require speeding up development of the $33 billion industry. It currently takes as long as 15 years to complete a major offshore wind project in the UK, according to Aurora Energy Research. Some of that time could be cut by simplifying the permitting process, but even then it may still take a decade.

The real timesaver would be installing turbines more quickly. Erecting the giant structures requires highly specialized and expensive ships known as jack-up vessels. When they get to the site of a new wind turbine, a moveable foundation descends to the seabed to hoist the vessel out of the waves so it can work without being pushed back and forth. Under ideal conditions, this can take as little as three hours, but that can also drag to 20 hours if the currents are strong.

Floating vessels that don’t have to be lifted up can complete work 50% faster than those commonly used today, according to clean energy research group BloombergNEF. “You can make installations more efficient,” said Amanda Ahl, a BloombergNEF analyst. Because ships don’t have to haul the heavy structures used to tie them to the seabed, they can carry materials for more turbines at a time. That means fewer voyages back and forth to shore that can sometimes take up to 10 hours.

The catch is that using ships that float makes the precise work of assembling wind turbines much more difficult. That’s where the robots come in.

X-Laboratory, a company founded by former European Space Agency researcher André Schiele, sells software and robotics systems to wind turbine construction companies that allows the giant cranes on their ships to be controlled remotely. The technology that Schiele helped develop — initially intended to help conduct research on other planets from Earth — may shave years off the time needed to put up a wind farm in the ocean.

One of the world’s biggest installers of offshore wind, Jan De Nul Group, is starting to adopt the technology. The company has moved some of its operations to ships that float while they work. The first vessel, named Les Alizes, will get to work later this year and be able to carry three times more weight than a similar vessel that also has to haul equipment to attach it to the ground.

As a start, Jan De Nul’s new ships will use X-Laboratory’s system to control a giant claw that will help compensate for any unexpected movements in the water. The technology could cut the total time to install a wind farm by more than 25% due to its ability to work in windier conditions. For now, the claw will only be used to install the foundations for wind turbines, not the more sensitive work of attaching blades.

The company is optimistic that the robotic technology will counter the challenges of working out at sea on floating vessels. A “few years ago it was thought this was too difficult to overcome,” said Geert Weymeis, the company’s head of offshore installation analysis. The claw “could be a game changer.”

Schiele recalls celebrating in 2015 as an astronaut held a joystick on the International Space Station and moved a four-wheeled robot in a lab in the Netherlands. It was a breakthrough for space research. But he quickly started thinking about other applications, which led to X-Laboratory and the wind turbine construction system.

“It’s nice to solve challenges like ‘How can we go to Mars?’” he said. “But the climate question is a much bigger challenge.”

(By Will Mathis)

.png)