,

,Science correspondent

Space chiefs are to investigate whether electricity could be beamed wirelessly from orbit into millions of homes.

The European Space Agency will this week likely approve a three-year study to see if having huge solar farms in space could work and be cost effective.

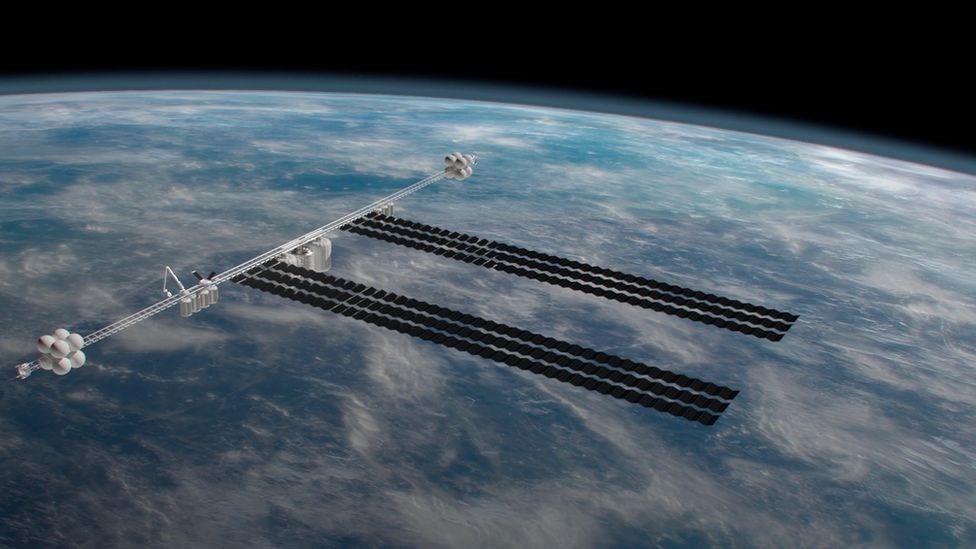

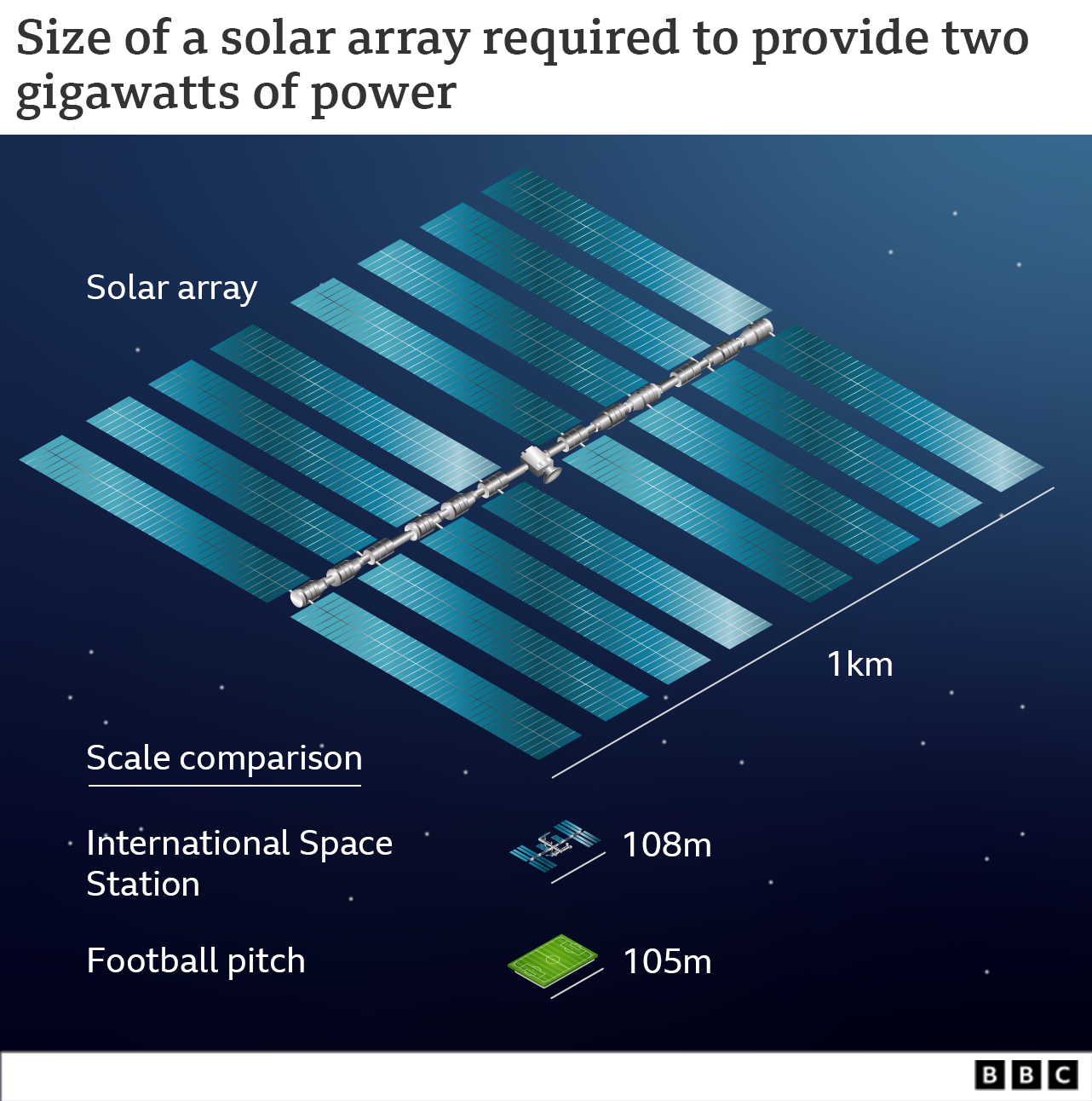

The eventual aim is to have giant satellites in orbit, each able to generate the same amount of electricity as a power station.

Research ministers will consider the idea at a Paris meeting on Tuesday.

While several organisations and other space agencies have looked into the idea, the so-called Solaris initiative would be the first to lay the ground for a practical plan to develop a space-based renewable energy generation system.

The programme is one of a number of proposals being considered by ministers at Esa's triennial council, which will decide the budget for the next phase of the space agency's plans for space exploration, environmental monitoring and communications.

Josef Aschbacher, who is Esa's director general, told BBC News that he believed that solar power from space could be of ''enormous'' help to address future energy shortages.

''We do need to convert into carbon neutral economies and therefore change the way we produce energy and especially reduce the fossil fuel part of our energy production," he said.

''If you can do it from space, and I'm saying if we could, because we are not there yet, this would be absolutely fantastic because it would solve a lot of problems."

The Sun's energy can be collected much more efficiently in space because there is neither night nor clouds. The idea has been around for more than 50 years, but it has been too difficult and too expensive to implement, until maybe now.

The game-changer has been the plummeting cost of launches, thanks to reusable rockets and other innovations developed by the private sector. But there have also been advances in robotic construction in space and the development of technology to wirelessly beam electricity from space to Earth.

Esa is seeking funds from its member nations for a research programme it calls Solaris, to see if these developments mean that it is now possible to develop spaced-based solar power reliably and cheaply enough to make it economically viable.

"The idea of space-based solar power is no longer science fiction," according to Esa's Dr Sanjay Vijendran, who is the scientist leading the Solaris initiative,

"The potential is there and we now need to really understand the technological path before a decision can be made to go ahead with trying to build something in space."

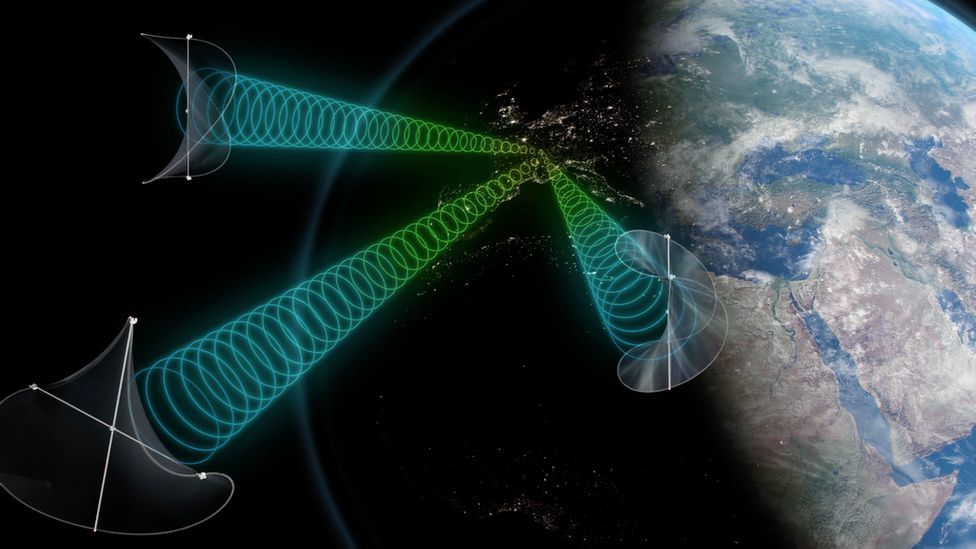

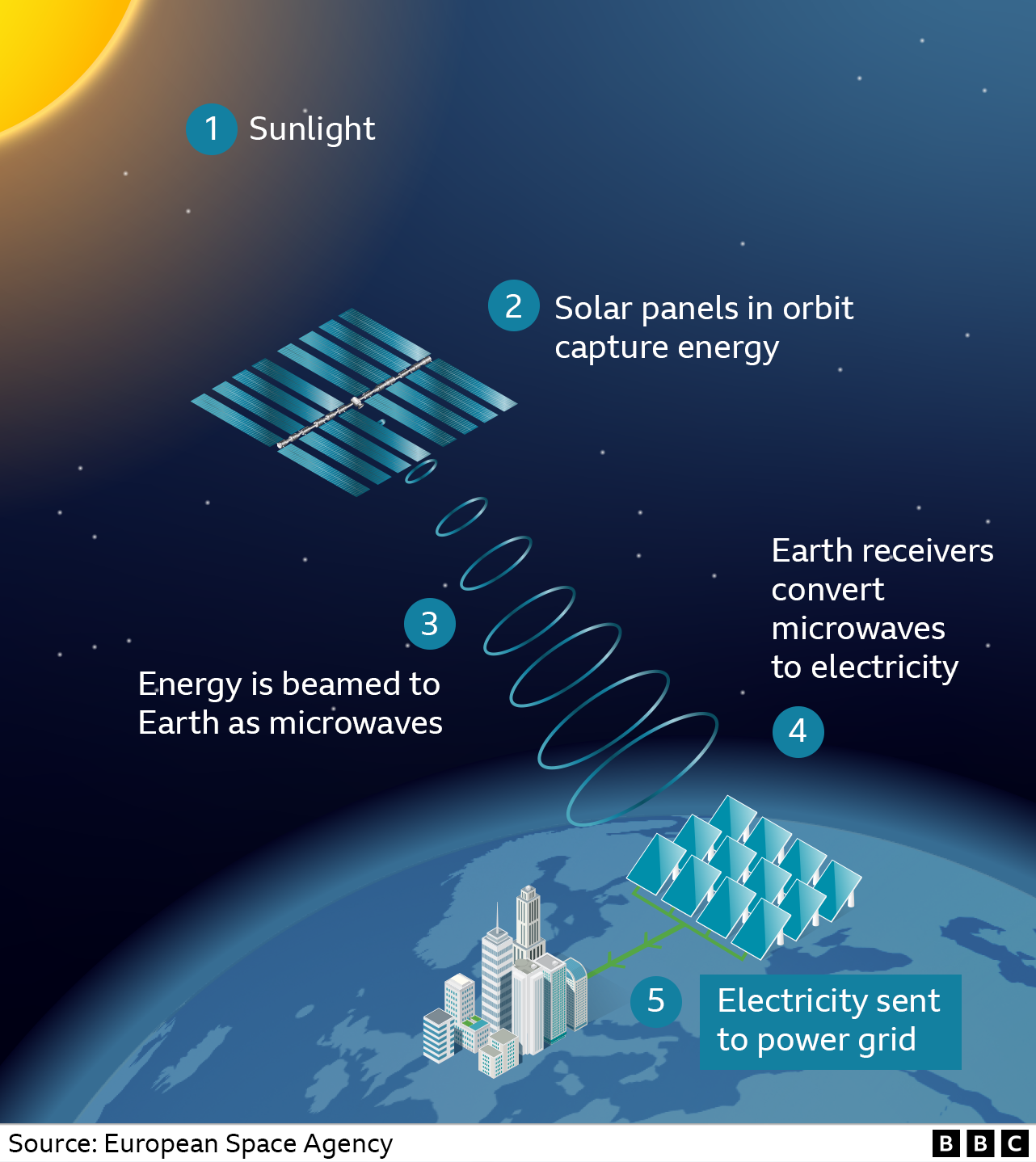

A key focus of the Solaris programme is to establish whether it is possible to transfer the solar energy collected in space to electricity grids on Earth. This can't of course be done with an extremely long cable, so it has to be sent wirelessly, using microwave beams.

The Solaris team has already shown that is is possible in principle to transmit electricity wirelessly safely and efficiently.

Engineers sent 2 KW of power collected from solar cells wirelessly to collectors more than 30 metres away at a demonstration at the aerospace firm, Airbus in Munich in September. It will be a big step up to send gigawatts of power over thousands of miles, but according to Jean Dominique Coste, who is a senior manager for Airbus's blue sky division, it could be achieved in a series of small steps.

''Our team of scientists have found no technical show-stoppers to prevent us from having space-based solar power," he said.

Two Kilowatts of electricity was sent wirelessly from the upright metal panel on the right to another panel on the other side of the room. In space a million times more power will have to be sent a million times further

Dr Ray Simpkin, who is the chief scientist of Emrod, the firm that developed the wireless beaming system, said that the technology was safe.

''Nothing will get fried,'' he told BBC News.

"The power is spread out over a such a large area that even at its peak intensity in the centre of the beam it will not be hazardous to animals or humans."

The US, China and Japan are also advanced in the race to develop space-based solar power and are expected to announce their own plans shortly. Separately from the ESA proposal, in the UK, a company, Space Solar, has been formed. It aims to demonstrate beaming power from space within six years, and doing so commercially within nine years.

A UK government assessment, independent of the Esa plan, concluded that it might be possible to have a satellite capable of producing the same amount of electricity as a power station, around 2 GW, by 2040, which is in line with Esa's own estimates. But, according to Dr Vijendran, with increased funding and greater political support it could be done within a decade, akin to the deadline set by US President John Kennedy in 1961 to send an American astronaut to the lunar surface.

"It could be our generation's equivalent of the moon shot," he says.

I

I/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/MWBZY277CFHOXHOE6QNAVXZNUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/H6YP4QIM3RAEJADKWF2FJ4WZVA.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/AZJSBSRIU5EPFAN3DBMEWCA37Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/UYYRDGRHMVDVRGVWE4QBMFULFI.jpg)