Olivia Konotey-Ahulu

Mon, January 16, 2023 at 10:00 PM MST·12 min read

(Bloomberg) -- If progress in 2022 is anything to go by, there’s reason to be optimistic about the global direction of travel when it comes to same-sex relationships, LGBTQ campaigners say.

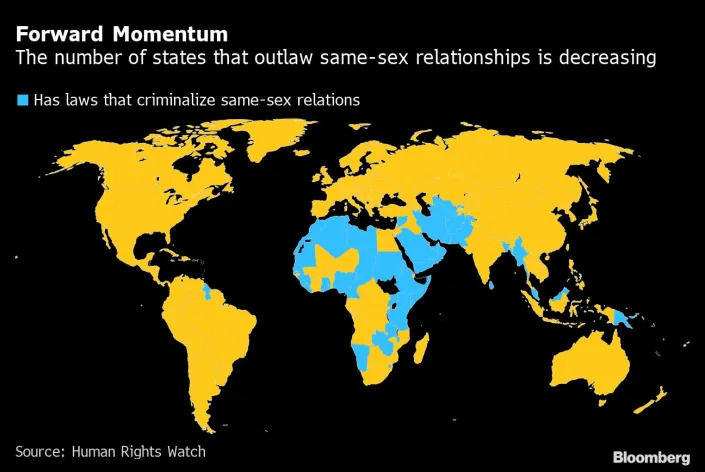

In the second half of the year, there was a flurry of movement to decriminalize same-sex intimacy in Singapore, St Kitts and Nevis, Barbados, and Antigua and Barbuda. These were some of the last holdouts among countries with histories of colonial-era laws prohibiting such activity. “It feels like something of a tipping point,” says Neela Ghoshal, Senior Director of Law, Policy and Research for global advocacy NGO Outright International. Such developments “allows us to really say that there is a global norm that same-sex intimacy should not be criminalized.”

Marriage equality has come a long way too, with countries from Cuba to Slovenia passing legislation last year; 33 governments have now legalized same-sex unions, triple the number compared to a decade earlier according to data from the advocacy group ILGA World.

Greece is one of a handful of countries to introduce a ban on so-called conversion therapy for minors during the year; France, Israel and New Zealand also took steps to make the practice of aiming to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity illegal in 2022. In Brazil, LGBTQ campaigners hope the re-election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva can row back some of the damage done by his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, while the US Congress rushed to pass the Respect for Marriage Act and protect statutory recognition of interracial and same-sex marriages.

But pockets of friction are growing over specific issues: one is the rights of transgender people. As of September, US lawmakers proposed more than 300 bills classed as anti-LGBTQ by the Human Rights Campaign; more than 40% of them targeted the trans community, the advocacy group said. The UK also saw its score on the ILGA-Europe Rainbow Index plummet more than any other country this year, partly due to its decision to exclude trans people from a ban on conversion therapy.

Conservative governments, especially those in Europe, have “weaponized” trans issues in recent years too to boost their political capital, said Julia Ehrt, executive director for ILGA World.

“The atmosphere, in particular in the UK but as well in Spain, has been quite hostile towards trans people,” she said. Although Spain passed a bill toward the end of the year that makes it one of the few places in the world where anyone over the age of 16 can easily change their gender on their ID card, the debate caused tensions to flare among its left-wing government and coincided with a jump in hate crimes in the country.

Read More: Spain’s Win for Transgender Rights Almost Tore the Country Apart

Meanwhile some governments actively sought to row back LGBTQ rights, such as Indonesia’s decision to ban sex outside of marriage, effectively criminalizing it for same-sex couples, as well as pushes in Russia and Ghana to crack down on so-called LGBTQ “propaganda.”

But overall progress on LGBTQ rights is moving forward, say Ehrt and Ghoshal, who are hopeful about what the new year could bring. “Ultimately I think the pendulum is swinging in the right direction,” Ghoshal said.

Here’s a snapshot of what that momentum looks like around the world.

India

India’s top most court is all set this year to consider the question of granting legal recognition to same-sex marriages. Some couples have knocked on the Supreme Court’s door with the argument that marriage equality is the logical next step for LGBTQ rights after consensual gay sex was decriminalized in the country in 2018.

Such a move could give India’s 1.4 billion people the right to have a same-sex marriage.

“The potential impact of such a ruling will be momentous,” said Kanav Narayan Sahgal, Communications Manager at Nyaaya, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. A law ironed out on same-sex marriage is also likely to open discussion on related aspects such as domestic violence, adoption, child-custody, and inheritance for the LGBTQ community, Sahgal said.

But the path ahead isn’t straightforward. Narendra Modi’s ruling Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) only recently opposed same-sex marriage before a state court. Speaking before Parliament in December, BJP lawmaker Sushil Modi urged the government to oppose same-sex marriage before the Supreme Court saying that it goes against the traditional ethos of the country.

“If the court does decide that such matters are best left to Parliament to decide, then I am afraid same-sex marriage will not be recognized in India as long as the BJP holds a majority,” says Sahgal who is also an LGBTQ rights activist. Eight state level polls likely to be held this year will indicate the pulse of the nation before an election for the next premier in 2024.

Meanwhile the Madras High Court in the southern state of Tamil Nadu has taken significant strides in making laws and policy inclusive for the LGBTQ community. A string of progressive decisions concerning rights of sexual minorities have been taken by the state on orders passed by the high court. These include penalizing police harassment of the community and declaring so-called conversion therapy as a professional misconduct for medical professionals. In 2023, Tamil Nadu is expected to release its draft policy for the LGBTQ community, becoming the first Indian state to do so. —Shruti Mahajan

Brazil

After four years of what they consider a complete stall in their battle for equal rights, the LGBTQ community in Brazil is now pushing for an extensive legislative agenda including same-sex marriage.

Left-wing Lula was inaugurated as president on Jan. 1 and groups have already asked him to pass more than eight related bills and several other proposals such as creating a role for the first national secretary for public policy focused on LGBTQ rights.

“We want better education, to be represented at the Executive branch, improvements in the health system, public safety, culture, all of it,” said Toni Reis, director and president of the National LGBTI+ Alliance. His is one of more than 100 associations that signed a letter addressed to Lula.

More than anything, the community is impassioned about making sure that rights safeguarded by the country’s top court are put into law. For example, Brazil's supreme court allowed same-sex marriage more than 10 years ago but this is still to be confirmed by Congress. They also hope to pass bills allowing transgender people to change their official ID to match their gender without showing proof of a change-of-sex surgery.

Each of these could be difficult tasks. The majority of legislators elected last October supported Bolsonaro, known for an agenda centered on conservative family values. Still, Congress will now have six representatives of the LGBTQ community including two transgender lawmakers, a record so far in Brazil.

“Bolsonaro wasn’t able to tear everything down, he wasn’t strong enough but we also had the supreme court defending our rights,” said Reis. “Now is our time to convince liberals from the right wing, evangelicals... We’ll have to earn their votes.” —Maria Eloisa Capurro

Slovenia

When Slovenia’s Constitutional Court unexpectedly ruled in July that same-sex couples had the right to marry, Centrih Albreht and his now-husband became one of the country’s first such couples to tie the knot.

It was a victory for the 36-year-old marketing specialist, who had watched his community suffer two referendum defeats on legalizing same-sex marriage. A party planned earlier to celebrate their civil union turned into a full-blown wedding in August. “It was a very special day for us and our families,” he said.

The first eastern European country to legalize same-sex unions and allow couples to adopt children, Slovenia contrasts sharply with the more conservative countries in the region, whose politicians still embrace anti-LGBTQ rhetoric. The EU took legal action in 2021 against Hungary and Poland for violating the community’s rights.

Those attitudes have had a direct impact in Slovenia, where many gay couples — often locals with partners from Eastern Europe — choose to build a home in that country, which Centrih Albreht sees as “a beacon” for more accepting society. The trend could strengthen further in 2023.

According to Lana Gobec, the head of the LGBTQ activist organization Legebitra, same sex-marriages will increase in Slovenia in 2023 and eventually converge with the proportion of marriages in the overall population. Gobec knows of several gay couples who already applied for adoption but tempers expectations over when the first adoption by a same-sex parent might happen because of the long process.

While Centrih Albreht sees the change in Slovenia as an important step to more acceptance, he sees the need for a bigger push for transgender rights. Citing this year’s abortion ruling by the US Supreme Court, he also worries progress can be reversed.

“The fight must always continue,” he said. “Expanding human rights has never hurt anyone. If anything, all of society benefits.” —Jan Bratanic

Greece

With a general election scheduled by April at the earliest, the country’s LGBTQ community has one key priority for the next government: marriage equality.

Greece passed legislation to recognize same-sex civil partnerships in 2015 and gender identity in 2017 but same-sex marriage hasn’t seen similar progress. Any possible move to legalize marriage between two people of the same sex will require changes to family law so that the state recognizes both members of the couple as parents and guardians of children rather than just a biological parent.

The same-sex unions didn’t provide the same access to rights as equal marriage would do, said Giannis Papagiannopoulos, a rights activist and publisher of Antivirus Magazine, Greece’s only LGBT publication. Lawmakers voting for equal marriage for the LGBTQI+ communities in Greece “would be a direct recognition of our families, our basic human rights and our very existence,” he said.

Few expected such progress to come from Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the current prime minister and leader of the center-right New Democracy party. While he hasn’t officially announced plans to legalize same-sex marriage, the premier is expected to address the issue during his next term if he wins the national ballot.

If he does, it would carry on the momentum set by the Greek leader after he was first elected. In 2021, he appointed a committee to draft a national strategy for improving LGBTQ rights. That strategy, which runs through 2025, acknowledges that rights for LGBTQ people “would not be complete without addressing the issue of marriage equality which, if established, would resolve numerous other issues associated with family law in Greece.”

The main opposition Syriza party of former premier Alexis Tsipras supports same-sex marriage and submitted a proposal in July which also proposes related measures such as the legalization of assisted reproduction for all couples.

Mitsotakis has introduced a number of reforms since 2021, such as lifting a ban on homosexual men making blood donations, outlawing in 2022 so-called sex normalizing surgeries on children and in September approving the official use of pre-exposure prophylactic drugs, commonly known as PrEP, to focus on the prevention of HIV infection rather than just on the treatment of the virus.

Greece has seen one of the the biggest jumps in ILGA’s ranking of LGBTQ rights among European countries following adoption of the strategy.

The introduction of PrEP, “is a step in the right direction for reducing HIV infection in the LGBTQ community,” said Giorgos Papadopetrakis, the vice chair of Positive Voice, an association for HIV-positive people in Greece. “Now, we’re just waiting to see how the decision will be implemented — how it will pass into action,” he said. —Paul Tugwell

United States

Progress on LGBTQ rights in America were “a mixed bag” in 2022, said Ehrt, the executive director of Outright International.

On the one hand, the historic Respect for Marriage Act Congress passed in December safeguards the rights to same-sex and interracial marriage from being rolled back in the same way abortion access has this year. But one of the first openly gay Black members of Congress, Mondaire Jones, said the legislation doesn’t go far enough, and doesn’t ensure marriage equality in every state. (Jones lost his bid for reelection in November, though more LGBTQ politicians were elected to Congress this cycle than ever before.)

With hundreds of anti-LGBTQ laws introduced at state-level during 2022, campaigners are also worried about a particular focus on rolling back rights among young people and transgender people. That trend includes limiting the participation of transgender people in sports that affirm their gender identity, as well as Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law which prohibits discussion about sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade.

Pressure to ban books with LGBTQ characters and themes at schools and public libraries has also increased. In messaging rolled out ahead of the midterms, the GOP led by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy listed anti-trans sports bills and legislation on parental rights among the party’s priorities.

Legislators in at least seven states proposed anti-drag bills ahead of the 2023 legislative session. These bills are often broad in nature, and many target people defined as “male or female impersonators.” LGBTQ advocates say they’re worried such language could be used to target transgender people. Other proposed bills target gender-affirming healthcare, particularly for children. Sarah Warbelow, legal director for the Human Rights Campaign described it as a “very intentional attack on LGBTQ youth from conservative legislatures across the country.”

The latter part of 2022 saw a surge in hostility toward the community, including the mass shooting at a LGBTQ club in Colorado, where five people were killed. The suspect now faces more than 300 charges including hate crimes. Reported anti-LGBTQ incidents, such as demonstrations and violence, have risen twelve-fold to almost 200 since 2020, according to a report by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project in November. —

Kelsey Butler, Ella Ceron and Olivia Konotey-Ahulu