Most adults in US, 16 other nations say belief in God, morality not always linked

Pew Research Center released the findings — that also hold true among most of those affiliated with a religion — from its Global Attitudes Survey.

(RNS) — Is a belief in God a prerequisite for being a moral person?

Most Americans say it is not, and majorities of adults in other countries with advanced economies agree.

Pew Research Center released the findings — that also hold true among most of those affiliated with a religion — from its Global Attitudes Survey on Thursday (April 20).

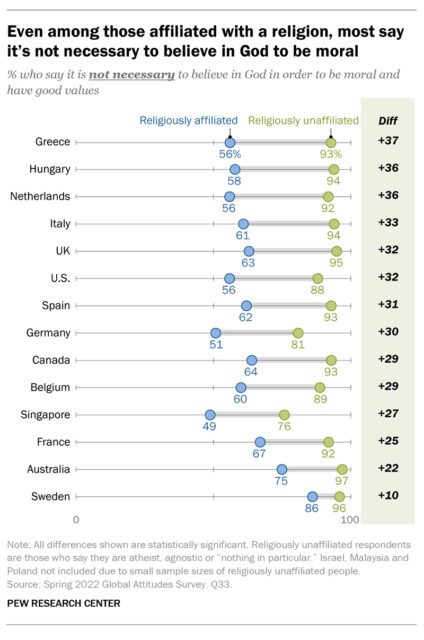

“(E)ven among people who are religiously affiliated, most do not think it is necessary to believe in God to have good values,” states the new report on questions asked in the spring of 2022. “In most countries surveyed, half or more of people who say they belong to a religion also say it is not necessary to believe in God to be moral.”

“Even among those affiliated with a religion, most say it’s not necessary to believe in God to be moral” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

In the U.S., 56% of the religiously affiliated said morality and good values do not have to be linked with a belief in God. Globally, countries with the highest percentages of religiously affiliated people agreeing with that statement included Sweden (86%) and Australia (75%).

But differences are more striking in some countries whose general populations were surveyed.

RELATED: Faith still shapes morals and values even after people are ‘done’ with religion

While at least 60% of Europeans and North Americans do not say belief in God and morality must be linked, Israelis are more split on that, with 50% agreeing and 47% saying such a belief is essential. About one-fifth of Malaysians say people can be moral without a belief in God, while more than three-quarters disagree with that view.

Based on research in 16 countries beyond the U.S., a median of about two-thirds of adults say people can be moral without a belief in God, a bit higher than the U.S. share.

Across the globe, there are different views depending on religious and political affiliation.

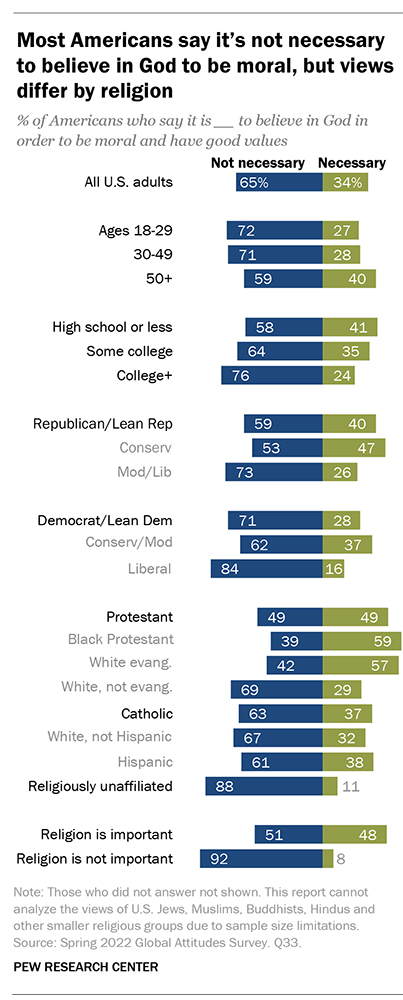

In the U.S., about 9 in 10 who say religion is not at all important or not too important to them believe morality and belief in God do not need to be linked, but just half of those who think it is somewhat or very important to them agree.

“Most Americans say it’s not necessary to believe in God to be moral, but views differ by religion” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

Black Protestants (39%) and white evangelicals (42%) were least likely among Americans to say it’s not essential to believe in God to be moral, while the religiously unaffiliated (88%) were the group most in agreement with that stance.

Democrats and those who lean Democratic are more likely than their Republican counterparts to say it is not essential to believe in God to be moral (71% compared with 59%). Americans younger than 50 and older adults reflect a similar difference in response.

“In nearly every country where political ideology is measured, people who place themselves on the political left are more likely than those on the political right to say that belief in God is not necessary to have good values,” the report states.

“In addition, younger adults in about half of the countries surveyed are significantly more likely than older respondents to say that a belief in God is not connected with morality.”

More than 4 in 5 Greek adults younger than 30, for instance, unlink morality from a belief in God, in contrast with half of Greek adults who are 50 and older (84% compared with 51%). Substantial age differences also occur in Canada, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Singapore and the United Kingdom.

Although the new report focused on countries with advanced economies, 2019 Pew research found that, among 34 nations, including some with developing or emerging economies, higher shares of people in nations with lower gross domestic products said believing in God was crucial for morality.

The new report’s findings were based on a survey of 3,581 U.S. adults from March 21-27, 2022, who took part in an online survey panel, with an overall margin of error of plus or minus 2.3 percentage points. Outside the U.S., the report relied on nationally representative surveys of an overall total of 18,782 adults from Feb. 14-June 3, 2022. In some countries the surveys were completed by phone and in others by face-to-face interviews or an online panel. The margin of error ranged from plus or minus 2.8 percentage points in Australia to plus or minus 4.5 percentage points in Hungary.

RELATED: Good without God? More Americans say amen to that