April 28, 2023

Source: Counterpunch

In mid-April, we hosted renowned linguist, political analyst, and activist Noam Chomsky for a speaking and Q&A event at Lehigh University as part of the Douglas Dialogues forum. The event was attended by hundreds of students, faculty, and staff, and provided the Lehigh University community an opportunity to engage in contemporary political issues with Professor Chomsky, as related to the rise of global and domestic extremism. This reflection looks at some of Chomsky’s insights, and what they tell us about the state of democracy in America today.

It’s been over two years since the January 6th insurrection, where thousands of far-right rioters stormed our nation’s Capitol in an attempt to stop the peaceful transfer of executive power. FBI director Christopher Wray referred to the insurrection as an act of “domestic terrorism,” and reports suggest that far-right extremists have killed more people in our country than have domestic Islamist fundamentalists since 9/11. In this political environment, Chomsky exposes the causes of rising rightwing extremism, and spent much of his time with the Lehigh community discussing this issue of growing concern.

When asked what he thinks of the rise of the right in U.S. politics today, Chomsky points out that this isn’t simply an American, but an international phenomenon. Citing the rising popularity of rightwing ethno-nationalists across the world from Nigel Farage in the UK and Marine LePen in France to the AFD Party in Germany, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and religious nationalists in Israel, Chomsky recognizes that, while each nation has its own unique flavor of rightwing nationalism, rising extremism is happening all over the world.

Chomsky emphasizes the role of neoliberalism as a force that fuels rightwing, authoritarian, and fascistic politics. He points to rising inequality and worker insecurity across the globe in the last 40 to 45 years, highlighting a “bitter, savage class war” that’s being fought by both major U.S. political parties, on behalf of plutocratic elites, and against the large majority of Americans who have seen their economic positions stagnate or decline during this period. In the U.S., a corporate elite has imposed a political-economic system that institutionalizes stagnant wages and household incomes, pressures workers to increase productivity, fuels an assault on labor unions, does nothing to stop spiraling health care costs and rising mortality, and that has grown the incarceration state, as the profits hoarded from these practices accrue to the top one percent of wealthy Americans who own and control the economy.

Chomsky cites a report from the Rand Corporation, which finds that U.S. business elites have siphoned off an incredible $50 trillion in additional wealth over the last three decades, at the expense of working, middle class, and poor Americans. The Rand report uses polite academic language, talking about rising economic inequality from 1975 to 2018, in which income and wealth growth have “not been evenly shared,” and with inequality having “increased substantially by most measures” to the tune of an additional $47 trillion captured by the wealthiest Americans, at the expense of the bottom 90 percent of income earners.

Chomsky is more direct and blunt in his language. He talks about how this class war has “opened the doors for the sheer robbery of the American public” on behalf of plutocratic elites. Chomsky argues that the intensifying class war is a perfect environment for an authoritarian demagogue to rise to power, playing on the fears and anxieties of an increasingly insecure citizenry. This demagogue – Chomsky cites Trump as exhibit A – tells his supporters that he loves them, while stabbing them in the back by further intensifying neoliberal policies such as business deregulation and tax cuts for the wealthy, which fuel not only rising inequality, but the global environmental crisis that springs from a lack of regulations on the fossil fuel industry. In classic Chomskyian style, he points to the incredible power of propaganda, with the fossil fuel industry playing the role of “merchants of doubt,” muddying the waters of public discourse on whether climate change is even real, thereby blunting potential government action on this mounting crisis. Trumpian-style demagoguery, Chomsky argues, is instrumental to direct public attention away from an elite driven class war, with public anger being stoked via the shameless exploitation of hot button culture war issues. Among them Chomsky includes anti-vaxxerism – which he points out “has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.” Another diversionary tactic is the mainstreaming of “great replacement” propaganda within the GOP and in rightwing media, which depicts white working-class Americans as under assault due to the immigration of non-white peoples, who threaten to make white people a minority. Finally, Chomsky talks about an authoritarian effort on the American right to demonize any group with expertise that might challenge the GOP, its deceptions, and its plutocratic supporters. These much-maligned experts include journalists, scientists, and medical professionals, among others with technical skills who may not echo GOP propaganda. As Chomsky argues, the message that’s delivered in this war on intellectualism is that “it’s not the corporate sector that is guilty” of shafting the American people, but rather “the liberal elites” and other technocrats, who are supposed appendages of the Democratic Party and working against normal Americans. Understandably, Chomsky finds this rising anti-intellectualism to be extremely disturbing, as it foments distrust, alienation, paranoid delusion, and isolation, which have undermined efforts to form progressive democratic social movements that might fight back against plutocracy in America.

One of the most important lessons Chomsky left his audience with is that the rise of extremism and plutocracy are not inevitable. If we want a more just society, we must organize and fight for one. It won’t just fall into our laps. Social movements have created change before, and they can do it again. But it’s up to us to make that dream a reality.

One of the first questions Chomsky was asked during the student Q&A was, “What do you see the future holding as tensions rise and class warfare becomes more pronounced?” He answered, “It’s up to you…. If only one side is engaged in class war, you know the outcome. If both sides are engaged, it’s quite different.”

Chomsky highlighted cycles of change in the 20th century. He described how labor unions were decimated by President Woodrow Wilson’s Red Scare and associated crackdowns from corporations in the 1920s. The decline of labor unions preceded the Gilded Age, a time of abject poverty and massive wealth inequality. Yet, the Gilded Age was met with an intense reaction from social movements. Labor unions and organizations like the AFL-CIO began to organize industrial actions and disruptive sit-down strikes. Such pressure, alongside a sympathetic White House under Franklin Roosevelt, led to the passage of the New Deal, which created the groundwork for social democratic institutions, including the welfare state, regulation of business, and worker protections. Take for example Social Security, which provides benefits to tens of millions of Americans today and is one of the most effective anti-poverty programs in U.S. history.

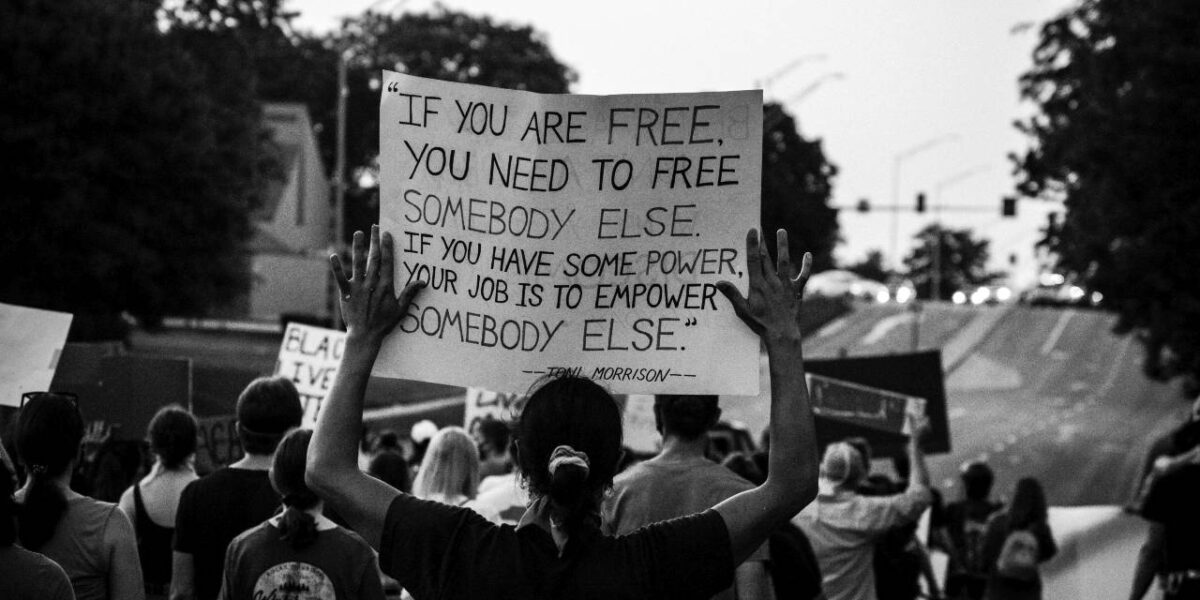

Yet, we don’t have to go back a century for examples of democratic movement successes. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests of 2020 were one of the largest, if not the largest, protests in U.S. history. As many as 26 million people reportedly participated in the protests. This was about 10 percent of the adult population. The protests preceded Executive Order 14074, which changed federal agency use-of-force policies. BLM also made significant changes to public awareness, and forced local police departments to confront their troubled histories of racism, racial profiling and police brutality. Research shows that the BLM protests shifted public discourse toward anti-racism. Analyses of social media searches and the news show an increased interest in terms like “mass incarceration,” “white supremacy,” and “systemic racism.” Such an interest was sustained even beyond the height of the protests during the summer of 2020. Other evidence suggests that the BLM movement increased perceptions of discrimination against Black people, and this prompted some vote switching from Donald Trump and third party candidates to Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election.

A second major lesson from Chomsky’s talk is that violence is not the answer to fighting back against rising inequality and the assault on democracy. Chomsky was asked during the Q&A: “Is the threat of violence the only mechanism that we have to either establish peace or progressive revolution?” He answered, “Would violence help overcome these problems? There’s no reason to believe that. Resorting to violence is moving into the arena where the enemy has the power. If you’re a tactician, you don’t move into the arena where the opponent is powerful, you move into the arena where the opponent is weak.” The “enemy” in this reference would seemingly refer to a plutocratic political-economic elite, which Chomsky targeted throughout his talk as the primary threat to American democracy.

Chomsky discussed how those in political power use protest-related violence to justify their opposition to social movements. He used the BLM protests of summer 2020 as an example, pointing to how, despite BLM being overwhelmingly non-violent, a fringe of protestors, and in some cases agitators, rioted, looting stores and destroying property. This played right into the hands of media outlets like Fox News, whose pundits loved the riots because they gave them a chance to demonize the movement. As numerous studies documented (see here and here), Fox News consistently tied rioting to BLM to tarnish the movement and its social justice objectives. Even though the vast majority of BLM protests have been peaceful, examples of violent protests were used to increase perceptions of the criminality and violence of BLM. Such perceptions diminish support for BLM and their goals for police reform.

Chomsky referred to violence as “a gift to the enemy.” Instead, change must come from “active organization and activism.” As he reminded the audience, it was the peaceful protests of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement that led to the passage of the Civils Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Martin Luther King (MLK) Jr. was inspired by Henry David Thoreau and Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy for nonviolence, and used it as the organizing principle for the Civil Rights Movement. In the Social Organization of Nonviolence (1959), MLK criticized violence, describing it as an unattractive social force, and argued that only self-defense is morally justified and able to gain popular sympathy. Yet, MLK did not advocate for passive resistance or resignation. He advocated for “militant nonviolence,” the consistent pressure of civil protest in the form of mass marches, boycotts, sit-ins, and strikes. Reinforcing Chomsky’s and MLK’s point, contemporary research shows that civil resistance campaigns have been twice as successful as violent campaigns in achieving political change.

We believe that Chomsky makes a provocative and compelling argument about the vitality of social movements and nonviolence to change. He is also right to identify how wealthy elites are engaged in a class war that utilizes culture war propaganda. When party officials rile up their base by drawing on transphobia, cultivating fear about critical race theory, stoking fear about an assault on Second Amendment rights, and mainstreaming “great replacement” propaganda, the party’s base becomes increasingly radicalized. The GOP base falls into this culture war messaging, despite being the victims of an elite class war. As we have found in our own national polling data out of Lehigh University’s Marcon Institute, only about 1 percent of people identifying as Republican also identify as upper-class, and only 11 percent identify as either upper-class or upper-middle class, meaning they hail from professional backgrounds that are likely to be part of the corporate-business class, or the group of white collar professionals on the periphery of the corporate upper class. Fifty-four percent of Republican Americans identify as middle-class, with another 26 and 9 percent respectively identifying as lower-middle or lower class. This means that the lion’s share of the 89 percent of Republicans who identify outside the upper class are the sorts of people who are likely to have been hurt by rising worker insecurity and intensifying inequality in the neoliberal era. Yet, these individuals embrace the GOP’s culture war, which directs attention away from the party’s active assault on its own base.

But there’s more to this story. Our work at Lehigh’s Marcon Institute documents how white supremacy is a social force that exercises ideological power over the public. It has always been a power in its own right in a country that historically idealized and practiced slavery, and later Jim Crow segregation, and continues to indulge in ethno-nationalist rhetoric that elevates whites to a dominant status. White supremacy has been constant, in various forms, throughout American history, and we shouldn’t relegate this factor to secondary status in explaining continued inequality in America today. Chomsky is right that racism is utilized as a weapon to reinforce classism among modern operatives of the plutocracy within the GOP. But racism also operates independently to reinforce white privilege and power at a time when the population is rapidly diversifying demographically away from a Caucasian white-identifying majority. We are talking today about a population in which – depending on the survey question asked – a third to half of Americans, and most republicans now embrace a mainstreamed version of white supremacy that accepts Great Replacement propaganda, celebrates confederate iconography, and elevates white identity to a national ideal. These are terrifying trends.

Yes, GOP elites are intensifying these reactionary social values by selling culture war propaganda as they kick their base – the vast majority of which are not wealthy – in the teeth on economic issues. But this is such a brutally effective method of control precisely because of the long-standing history of xenophobia and white supremacy that defines American political culture.

Noam Chomsky is an inspiration in the fight against propaganda. Throughout the discussion, he encouraged students to ask questions about how and where we get our information, to think about power relationships, how events are framed, who is doing the framing, and what they stand to gain. Through this intentional and reflective process, we become critically educated. Chomsky’s critical insights provide an invaluable guide for helping to develop consciousness about the inequities in our world, their causes, and what we can collectively do about them.

Source: Counterpunch

In mid-April, we hosted renowned linguist, political analyst, and activist Noam Chomsky for a speaking and Q&A event at Lehigh University as part of the Douglas Dialogues forum. The event was attended by hundreds of students, faculty, and staff, and provided the Lehigh University community an opportunity to engage in contemporary political issues with Professor Chomsky, as related to the rise of global and domestic extremism. This reflection looks at some of Chomsky’s insights, and what they tell us about the state of democracy in America today.

It’s been over two years since the January 6th insurrection, where thousands of far-right rioters stormed our nation’s Capitol in an attempt to stop the peaceful transfer of executive power. FBI director Christopher Wray referred to the insurrection as an act of “domestic terrorism,” and reports suggest that far-right extremists have killed more people in our country than have domestic Islamist fundamentalists since 9/11. In this political environment, Chomsky exposes the causes of rising rightwing extremism, and spent much of his time with the Lehigh community discussing this issue of growing concern.

When asked what he thinks of the rise of the right in U.S. politics today, Chomsky points out that this isn’t simply an American, but an international phenomenon. Citing the rising popularity of rightwing ethno-nationalists across the world from Nigel Farage in the UK and Marine LePen in France to the AFD Party in Germany, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and religious nationalists in Israel, Chomsky recognizes that, while each nation has its own unique flavor of rightwing nationalism, rising extremism is happening all over the world.

Chomsky emphasizes the role of neoliberalism as a force that fuels rightwing, authoritarian, and fascistic politics. He points to rising inequality and worker insecurity across the globe in the last 40 to 45 years, highlighting a “bitter, savage class war” that’s being fought by both major U.S. political parties, on behalf of plutocratic elites, and against the large majority of Americans who have seen their economic positions stagnate or decline during this period. In the U.S., a corporate elite has imposed a political-economic system that institutionalizes stagnant wages and household incomes, pressures workers to increase productivity, fuels an assault on labor unions, does nothing to stop spiraling health care costs and rising mortality, and that has grown the incarceration state, as the profits hoarded from these practices accrue to the top one percent of wealthy Americans who own and control the economy.

Chomsky cites a report from the Rand Corporation, which finds that U.S. business elites have siphoned off an incredible $50 trillion in additional wealth over the last three decades, at the expense of working, middle class, and poor Americans. The Rand report uses polite academic language, talking about rising economic inequality from 1975 to 2018, in which income and wealth growth have “not been evenly shared,” and with inequality having “increased substantially by most measures” to the tune of an additional $47 trillion captured by the wealthiest Americans, at the expense of the bottom 90 percent of income earners.

Chomsky is more direct and blunt in his language. He talks about how this class war has “opened the doors for the sheer robbery of the American public” on behalf of plutocratic elites. Chomsky argues that the intensifying class war is a perfect environment for an authoritarian demagogue to rise to power, playing on the fears and anxieties of an increasingly insecure citizenry. This demagogue – Chomsky cites Trump as exhibit A – tells his supporters that he loves them, while stabbing them in the back by further intensifying neoliberal policies such as business deregulation and tax cuts for the wealthy, which fuel not only rising inequality, but the global environmental crisis that springs from a lack of regulations on the fossil fuel industry. In classic Chomskyian style, he points to the incredible power of propaganda, with the fossil fuel industry playing the role of “merchants of doubt,” muddying the waters of public discourse on whether climate change is even real, thereby blunting potential government action on this mounting crisis. Trumpian-style demagoguery, Chomsky argues, is instrumental to direct public attention away from an elite driven class war, with public anger being stoked via the shameless exploitation of hot button culture war issues. Among them Chomsky includes anti-vaxxerism – which he points out “has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.” Another diversionary tactic is the mainstreaming of “great replacement” propaganda within the GOP and in rightwing media, which depicts white working-class Americans as under assault due to the immigration of non-white peoples, who threaten to make white people a minority. Finally, Chomsky talks about an authoritarian effort on the American right to demonize any group with expertise that might challenge the GOP, its deceptions, and its plutocratic supporters. These much-maligned experts include journalists, scientists, and medical professionals, among others with technical skills who may not echo GOP propaganda. As Chomsky argues, the message that’s delivered in this war on intellectualism is that “it’s not the corporate sector that is guilty” of shafting the American people, but rather “the liberal elites” and other technocrats, who are supposed appendages of the Democratic Party and working against normal Americans. Understandably, Chomsky finds this rising anti-intellectualism to be extremely disturbing, as it foments distrust, alienation, paranoid delusion, and isolation, which have undermined efforts to form progressive democratic social movements that might fight back against plutocracy in America.

One of the most important lessons Chomsky left his audience with is that the rise of extremism and plutocracy are not inevitable. If we want a more just society, we must organize and fight for one. It won’t just fall into our laps. Social movements have created change before, and they can do it again. But it’s up to us to make that dream a reality.

One of the first questions Chomsky was asked during the student Q&A was, “What do you see the future holding as tensions rise and class warfare becomes more pronounced?” He answered, “It’s up to you…. If only one side is engaged in class war, you know the outcome. If both sides are engaged, it’s quite different.”

Chomsky highlighted cycles of change in the 20th century. He described how labor unions were decimated by President Woodrow Wilson’s Red Scare and associated crackdowns from corporations in the 1920s. The decline of labor unions preceded the Gilded Age, a time of abject poverty and massive wealth inequality. Yet, the Gilded Age was met with an intense reaction from social movements. Labor unions and organizations like the AFL-CIO began to organize industrial actions and disruptive sit-down strikes. Such pressure, alongside a sympathetic White House under Franklin Roosevelt, led to the passage of the New Deal, which created the groundwork for social democratic institutions, including the welfare state, regulation of business, and worker protections. Take for example Social Security, which provides benefits to tens of millions of Americans today and is one of the most effective anti-poverty programs in U.S. history.

Yet, we don’t have to go back a century for examples of democratic movement successes. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests of 2020 were one of the largest, if not the largest, protests in U.S. history. As many as 26 million people reportedly participated in the protests. This was about 10 percent of the adult population. The protests preceded Executive Order 14074, which changed federal agency use-of-force policies. BLM also made significant changes to public awareness, and forced local police departments to confront their troubled histories of racism, racial profiling and police brutality. Research shows that the BLM protests shifted public discourse toward anti-racism. Analyses of social media searches and the news show an increased interest in terms like “mass incarceration,” “white supremacy,” and “systemic racism.” Such an interest was sustained even beyond the height of the protests during the summer of 2020. Other evidence suggests that the BLM movement increased perceptions of discrimination against Black people, and this prompted some vote switching from Donald Trump and third party candidates to Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election.

A second major lesson from Chomsky’s talk is that violence is not the answer to fighting back against rising inequality and the assault on democracy. Chomsky was asked during the Q&A: “Is the threat of violence the only mechanism that we have to either establish peace or progressive revolution?” He answered, “Would violence help overcome these problems? There’s no reason to believe that. Resorting to violence is moving into the arena where the enemy has the power. If you’re a tactician, you don’t move into the arena where the opponent is powerful, you move into the arena where the opponent is weak.” The “enemy” in this reference would seemingly refer to a plutocratic political-economic elite, which Chomsky targeted throughout his talk as the primary threat to American democracy.

Chomsky discussed how those in political power use protest-related violence to justify their opposition to social movements. He used the BLM protests of summer 2020 as an example, pointing to how, despite BLM being overwhelmingly non-violent, a fringe of protestors, and in some cases agitators, rioted, looting stores and destroying property. This played right into the hands of media outlets like Fox News, whose pundits loved the riots because they gave them a chance to demonize the movement. As numerous studies documented (see here and here), Fox News consistently tied rioting to BLM to tarnish the movement and its social justice objectives. Even though the vast majority of BLM protests have been peaceful, examples of violent protests were used to increase perceptions of the criminality and violence of BLM. Such perceptions diminish support for BLM and their goals for police reform.

Chomsky referred to violence as “a gift to the enemy.” Instead, change must come from “active organization and activism.” As he reminded the audience, it was the peaceful protests of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement that led to the passage of the Civils Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Martin Luther King (MLK) Jr. was inspired by Henry David Thoreau and Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy for nonviolence, and used it as the organizing principle for the Civil Rights Movement. In the Social Organization of Nonviolence (1959), MLK criticized violence, describing it as an unattractive social force, and argued that only self-defense is morally justified and able to gain popular sympathy. Yet, MLK did not advocate for passive resistance or resignation. He advocated for “militant nonviolence,” the consistent pressure of civil protest in the form of mass marches, boycotts, sit-ins, and strikes. Reinforcing Chomsky’s and MLK’s point, contemporary research shows that civil resistance campaigns have been twice as successful as violent campaigns in achieving political change.

We believe that Chomsky makes a provocative and compelling argument about the vitality of social movements and nonviolence to change. He is also right to identify how wealthy elites are engaged in a class war that utilizes culture war propaganda. When party officials rile up their base by drawing on transphobia, cultivating fear about critical race theory, stoking fear about an assault on Second Amendment rights, and mainstreaming “great replacement” propaganda, the party’s base becomes increasingly radicalized. The GOP base falls into this culture war messaging, despite being the victims of an elite class war. As we have found in our own national polling data out of Lehigh University’s Marcon Institute, only about 1 percent of people identifying as Republican also identify as upper-class, and only 11 percent identify as either upper-class or upper-middle class, meaning they hail from professional backgrounds that are likely to be part of the corporate-business class, or the group of white collar professionals on the periphery of the corporate upper class. Fifty-four percent of Republican Americans identify as middle-class, with another 26 and 9 percent respectively identifying as lower-middle or lower class. This means that the lion’s share of the 89 percent of Republicans who identify outside the upper class are the sorts of people who are likely to have been hurt by rising worker insecurity and intensifying inequality in the neoliberal era. Yet, these individuals embrace the GOP’s culture war, which directs attention away from the party’s active assault on its own base.

But there’s more to this story. Our work at Lehigh’s Marcon Institute documents how white supremacy is a social force that exercises ideological power over the public. It has always been a power in its own right in a country that historically idealized and practiced slavery, and later Jim Crow segregation, and continues to indulge in ethno-nationalist rhetoric that elevates whites to a dominant status. White supremacy has been constant, in various forms, throughout American history, and we shouldn’t relegate this factor to secondary status in explaining continued inequality in America today. Chomsky is right that racism is utilized as a weapon to reinforce classism among modern operatives of the plutocracy within the GOP. But racism also operates independently to reinforce white privilege and power at a time when the population is rapidly diversifying demographically away from a Caucasian white-identifying majority. We are talking today about a population in which – depending on the survey question asked – a third to half of Americans, and most republicans now embrace a mainstreamed version of white supremacy that accepts Great Replacement propaganda, celebrates confederate iconography, and elevates white identity to a national ideal. These are terrifying trends.

Yes, GOP elites are intensifying these reactionary social values by selling culture war propaganda as they kick their base – the vast majority of which are not wealthy – in the teeth on economic issues. But this is such a brutally effective method of control precisely because of the long-standing history of xenophobia and white supremacy that defines American political culture.

Noam Chomsky is an inspiration in the fight against propaganda. Throughout the discussion, he encouraged students to ask questions about how and where we get our information, to think about power relationships, how events are framed, who is doing the framing, and what they stand to gain. Through this intentional and reflective process, we become critically educated. Chomsky’s critical insights provide an invaluable guide for helping to develop consciousness about the inequities in our world, their causes, and what we can collectively do about them.