Victor Tangermann

Thu, February 8, 2024

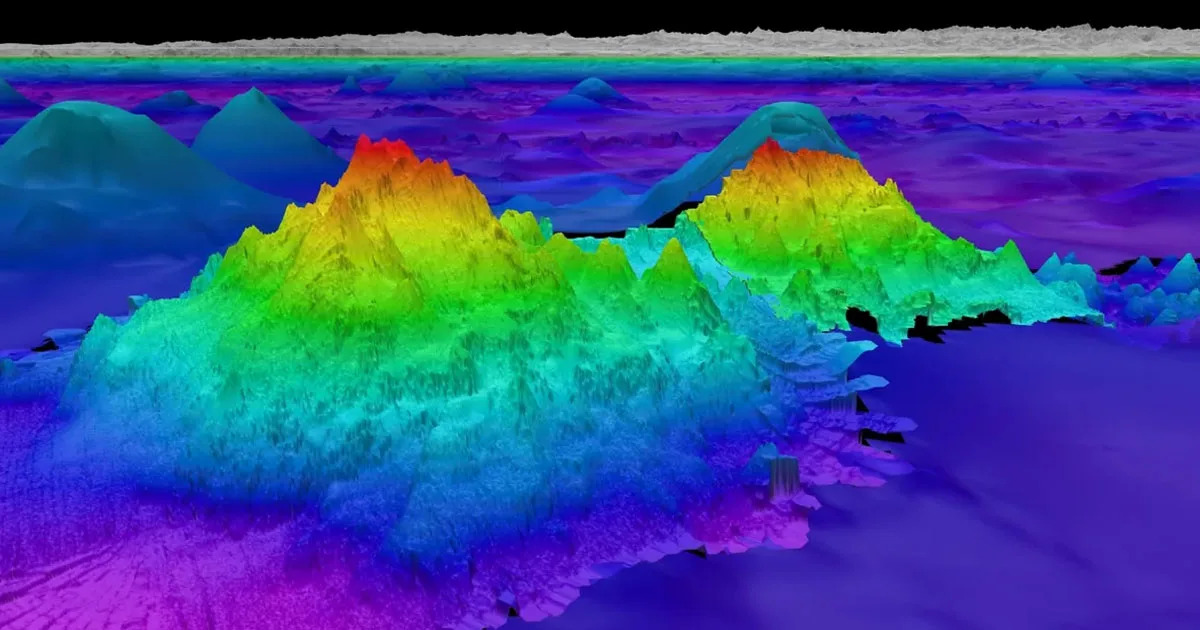

Underwater Mountain

A team of scientists on board an exploration vessel off the coast of South America have made a startling discovery: four previously unknown massive underwater mountains, ranging from 5,200 to 8,800 feet tall. The discovery highlights just how little we know about the oceans covering much of our planet. According to recent estimates, more than 80 percent of the ocean has never been mapped, let alone explored.

"The tallest is over one-and-a-half miles in height, and we didn’t really know it was there," Schmidt Ocean Institute's Jyotika Virmani — whose team has been studying "seamounts" from on board the vessel Falkor — told New Scientist.

Gravity Anomalies

Using sonar equipment, Virmani and team investigated gravity anomalies while sailing down from Costa Rica to Chile. These anomalies are usually the result of a hard-to-discern mass — in this case, entire mountains sticking out of the ocean floor.

"I was thinking one, maybe two, but to find four is incredible," Virmani told New Scientist. "It does show how much we don’t know of what’s out there."

Thanks to their sloped sides, seamounts are usually teeming with life. Last year, an international team of scientists, including Virmani, discovered a deep-sea octopus nursery near a low-temperature hydrothermal vent by a previously unknown seamount off the coast of Costa Rica.

Virmani and his team have discovered 29 seamounts so far, a tiny fraction of the mountains we have yet to discover.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Ocean Exploration organization, there are likely more than 100,000 of them that are at least 3,300 feet high.

A different study last year examined global satellite observations, concluding that there were nearly 20,000 seamounts still to be found despite more than 24,600 that have already been mapped.

"The fact that we don’t have maps of our seafloor is crazy," University of Plymouth marine biologist Kerry Howell, who was not involved in the research, told New Scientist.

Especially thanks to their incredible biodiversity, it's more important than ever to study these hiding giants. Fortunately, scientists have been using high-tech mapping techniques to get a better view — research that could greatly support ongoing conversation efforts.

Colossal underwater canyon discovered near seamount deep in the Mediterranean Sea

Sascha Pare

Thu, February 8, 2024

An underwater cave leading to a canyon.

Scientists have discovered a giant underwater canyon in the eastern Mediterranean Sea that likely formed just before the sea transformed to a mile-high salt field.

The canyon formed around 6 million years ago, at the onset of the Messinian salinity crisis (MSC), when the Gibraltar gateway between the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea narrowed and eventually pinched shut due to shifts in tectonic plates. The Mediterranean Sea became isolated from the world's oceans and dried up for roughly 700,000 years, leaving behind a vast expanse of salt up to 2 miles (3 kilometers) thick in some places.

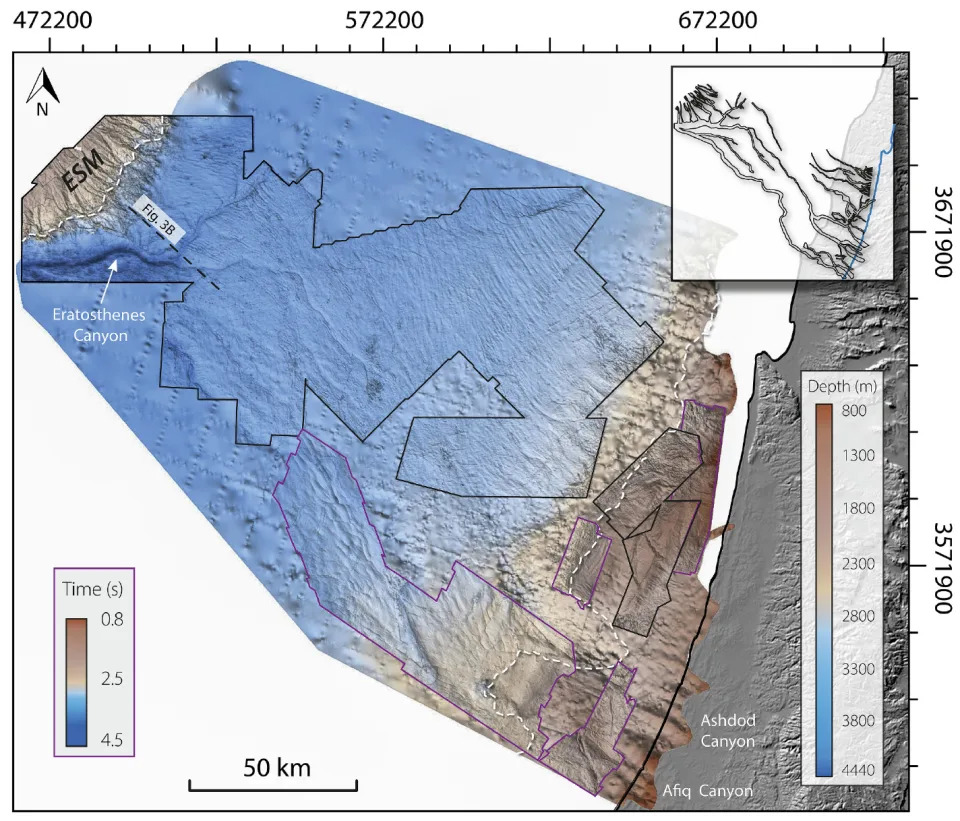

As sea levels dropped, increasingly salty currents eroded the seabed and incised gullies several hundred feet deep along the steepest edges of the Mediterranean Sea. In a study published in the January issue of the journal Global and Planetary Change, researchers now describe a giant U-shaped canyon located 75 miles (120 km) south of Cyprus, in the depths of the Mediterranean's Levant Basin.

The 1,640-foot-deep (500 meters) and 33,000-foot-wide (10 km) canyon, which the researchers named after the nearby Eratosthenes seamount, likely formed underwater shortly before salt piled onto the seabed. Unlike the more coastal gullies, the canyon had no older "pre-salt" roots, according to the study.

Related: 6 million-year-old 'fossil groundwater pool' discovered deep beneath Sicilian mountains

"To explain the submarine formation of the Eratosthenes Canyon, we suggest incision by dense gravity currents scratching and carving the deep-water seafloor," the researchers wrote in the study.

A map of the study area off the coast of Israel.

Weighed down with salt and sediment, these currents rushed along faster than the surrounding water and gradually scooped out enough of the seabed to form the colossal canyon. Precisely when this occurred remains unclear, but it likely coincided with the beginning of the MSC — between 5.6 million and 6 million years ago, according to the study. The incision process may have lasted anywhere from tens of thousands to half a million years.

The discovery sheds light on a decades-long debate over whether Messinian gullies and canyons that now lie underwater formed above or below the sea surface. "This new evidence strengthens the arguments that at least part of the erosion across continental margins occurred [below water]," the researchers wrote.

RELATED STORIES

—Supervolcano 'megabeds' discovered at bottom of sea point to catastrophic events in Europe every 10,000 to 15,000 years

—Underwater Santorini volcano eruption 520,000 years ago was 15 times bigger than record-breaking Tonga eruption

—Never-before-seen volcanic magma chamber discovered deep under Mediterranean, near Santorini

The newly discovered canyon sits within a wider network of canyons and channels in an area known as the Levant Basin, which extends from the coast of Syria in the north to Gaza in the south, and northwest toward Cyprus.

To the northwest of the canyon, beyond the Eratosthenes seamount, sits the much deeper and older Herodotus basin, which receives currents loaded with sediment from the southeast. These currents may have crossed the area that now boasts the Eratosthenes Canyon long before it was incised, according to the study.

"The absence of older roots under the Eratosthenes Canyon does not rule out the possibility that a shallow pre-MSC channel system predated the Eratosthenes Canyon," the researchers wrote.