Hannah Osborne

Thu, February 8, 2024

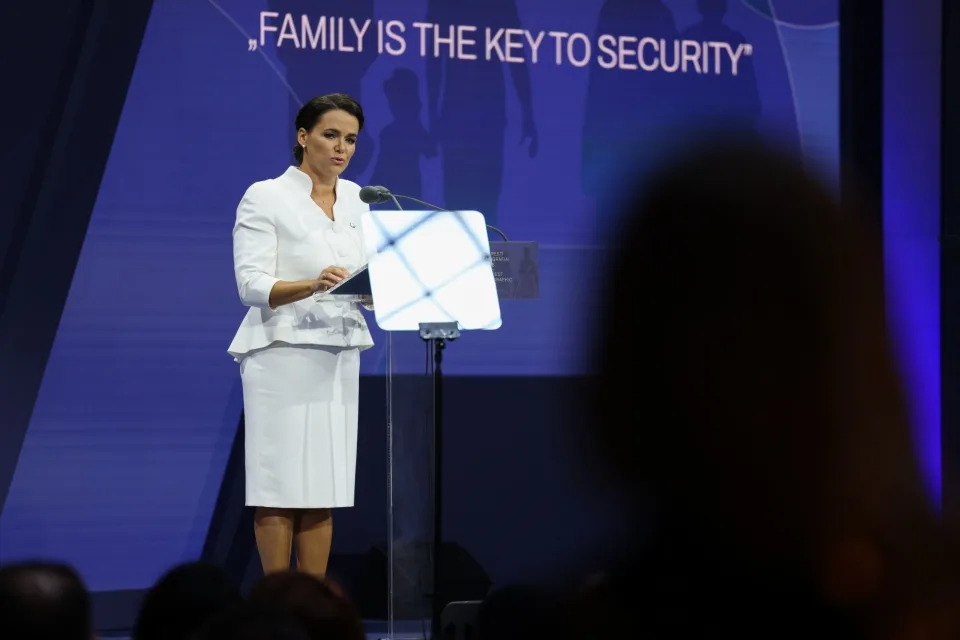

An aerial view shows lava after volcano eruption northeast of Sylingarfell, near Grindavik, Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland early Thursday, February 8, 2024.

Magma flowed into the dike beneath Grindavík at an unprecedented rate of 261,000 cubic feet per second (7,400 cubic meters per second) before the volcano first erupted in Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula, according to a new study.

"We were very surprised," lead author Freysteinn Sigmundsson, a geophysicist at the University of Iceland, told Live Science in an email. During the three previous eruptions in the region that took place between 2021 and 2023, magma flow into the dike was estimated to be less than 3,500 cubic feet per second (100 cubic m per second). "For the Grindavík dike it was almost 100 times higher," Sigmundsson said.

A 9.3-mile (15 kilometers) magma dike — a near-vertical tunnel running from the magma chamber beneath — formed beneath Grindavík in November, 2023,. At that point the region experienced a massive increase in seismic activity. Officials evacuated the fishing town, which has a population of around 3,800, given the risk of an eruption.

The volcano erupted on Dec. 18, with a 2.5-mile (4 km) fissure opening and sending lava spewing up to 100 feet (30 meters) into the air. The volcano erupted again on Jan 14., with two fissures opening on the outskirts of Grindavík. A third eruption occurred today (Feb. 8), with a 2-mile-long (3 km) fissure opening up near Mount Sundhnúkur to the north of Grindavík. The events are part of a millenia-long cycle that fuels eruptions.

Related: 'Time's finally up': Impending Iceland eruption is part of centuries-long volcanic pulse

Molten lava is seen overflowing the road leading to the famous tourist destination

In a new study published Feb. 8 in the journal Science, researchers examined the formation of the dike that led to the eruptions by combining satellite-based observations and seismic measurements, along with physical models. They found the magma flowed from the chamber into the dike at an exceptionally fast rate, comparable to the estimated rate of the 1783/84 eruption of Laki, which is around 130 miles (209 km) west of Grindavík . Within a year of the 8-month-long eruption, 60% of the country's livestock and 20% of the population died.

The Reykjanes Peninsula sits at the boundary of the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates. This section of the boundary has been stretching without any eruptions in the last 800 years. The Grindavík dike formed after magma accumulated about 3.1 miles (5 km) beneath the surface in what is known as a magma domain.

"A magma body is like an 'expanding balloon' inside the Earth, that can rupture," Sigmundsson said. The scientists found that the eruption took place with only modest overpressure — the amount of pressure that exceeds the surrounding pressure at that depth. This modest pressure alone could not have led to such immense speeds of magma flow.

"It means that other factors were important in explaining the fast magma flow — namely the forces due to the prior stretching of the crust (tension) as well as a large fracture on the boundary on the magma domain," Sigmundsson said. "The stretching forces contributed very significantly to the driving pressure for magma flow in the dike, causing the very fast flow."

RELATED STORIES

—'Hunter-gatherers must have gazed in horror': What would Toba's supereruption have been like for our ancient relatives?

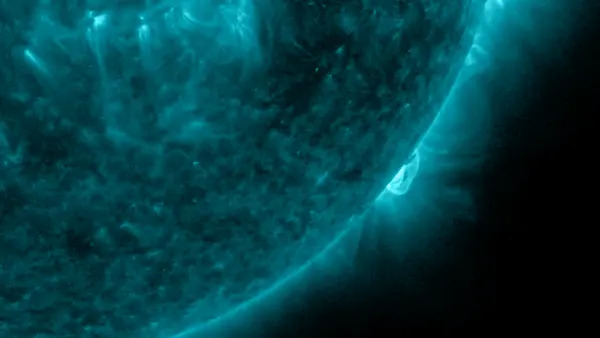

—Heat bursts from Iceland's recent eruptions in eerie NASA satellite image

—'The area has reactivated': Iceland volcano gears towards another eruption leaving Grindavík in precarious position

Discovering such a high inflow rate of magma has implications for other volcanoes. A dike with a high inflow rate of magma is potentially more hazardous than those filling at lower speeds. But it's also important to place the fill rate in context of the geological setting, as this will help determine the likelihood of magma reaching the surface.

The ability of this chamber to fill so quickly also has implications for future hazards on the Reykjanes Peninsula — even areas not in the direct path of erupting magma.

"The consequences of extensive faulting and fracturing above the dike in Grindavík, showed how very destructive such events can be, even without an eruption," Sigmundsson said.

How an unprecedented magma river surged beneath an Iceland town

Daniel Lawler

Thu, February 8, 2024

The latest fissure to break open and spew lava in southwestern Iceland (HANDOUT)

A river of magma flowed underneath an Icelandic fishing village late last year at a rate never before recorded, scientists said Thursday, as the region suffered yet another dramatic eruption.

Authorities in Iceland declared a state of emergency on Thursday as lava burst a key water pipe during the third volcanic fissure to hit the western Reykjanes peninsula since December.

Before 2021, the peninsula had not seen an eruption in 800 years, suggesting that volcanic activity in the region has reawoken from its slumber.

After analysing how magma shot up from a reservoir deep underground through a long, thin "vertical sheet" kilometres below the village of Grindavik in November, researchers warn that this activity is showing no signs of slowing down.

That prediction seemed to be borne out by the latest fissure that split the Earth's surface near the now-evacuated village, which occurred just hours before the new study was published in the journal Science.

Lead study author Freysteinn Sigmundsson, a researcher at the University of Iceland's Nordic Volcanological Centre, told AFP that it was difficult to say how long this new era of eruptions would continue.

But he estimated there were still months of uncertainty ahead for the threatened region.

- A mighty molten river -

Over six hours on November 10, the surging magma created a so-called dyke underground that is 15 kilometres (nine miles) long and four kilometres (2.5 miles) high but only a few metres wide, the study said.

Before Thursday's eruption, 6.5 million cubic metres of magma had accumulated below the region encompassing Grindavik, according to the Icelandic Meteorological Office.

The magma had flowed at 7,400 cubic metres per second, "a scale we have not measured before" in Iceland or elsewhere, Sigmundsson said.

For comparison, the average flow of the Seine river in Paris is just 560 cubic metres a second. The magma flow was closer to those of larger rivers such as the Danube or Yukon.

The magma flow in November was also 100 times greater than those seen before the recent eruptions on the peninsula from 2021 to 2023, Sigmundsson said.

"The activity is speeding up," he said.

The November magma flow precipitated more serious eruptions in December, last month and again on Thursday.

Increasing underground pressure has also led to hundreds of earthquakes and pushed the ground upwards a few millimetres every day, creating huge cracks in the ground and damaging infrastructure in and around Grindavik.

The hidden crevasses that have riddled the town likely pose more danger than lava, Sigmundsson said, pointing to one discovered in the middle of a sports pitch earlier this week.

- More magma to come -

The village, as well as the nearby Svartsengi power plant and the famed Blue Lagoon geothermal spa, have been repeatedly evacuated because of the eruption threats.

The long-term viability of parts of the region sitting on such volatile ground has become a matter of debate.

Sigmundsson emphasised that such decisions were up to the authorities, but said this was definitely "a period of uncertainty for the town of Grindavik".

"We need to be prepared for a lot more magma to come to the surface," he said.

The researchers used seismic measurements and satellite data to model what was driving the magma flow.

Iceland sits on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a crack in the ocean floor separating the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates.

As these plates have slowly moved apart over the last eight centuries, "tectonic stress" built up that was a key driving force for magma to surge through the underground geological crack, Sigmundsson said.

The researchers hope their analysis could inform efforts to understand what causes eruptions in other areas of the world.

Volcano in Iceland erupts for the third time in two months

Laura Baisas

Thu, February 8, 2024

Molten lava overflows the road leading to the Blue Lagoon geothermal spa, a popular tourist destination in western Iceland.

A newly active volcano system in southwestern Iceland erupted again on Thursday February 8. This is the third eruption since December 2023 on the Reykjanes Peninsula, which is home to about 31,000 residents and is one of the most populated areas of the island nation. This new eruption also prompted an evacuation of the Blue Lagoon spa, a popular tourist destination and geothermal spa.

According to Iceland’s Meteorological Office, the eruption occurred at 6 a.m. local time northeast of Mount Sýlingarfell. The orange glow of lava was visible from the capital city of Reykjavík, about 30 miles away from the eruption. The eruption began to slow as of 2:45 p.m. local time and is concentrated in three main areas. The fissure is estimated to be close to two miles wide and erupted about two and a half miles away from the town of Grindavík. A stream of lava flowed over the main road that connects the town to the capital. Grindavík was evacuated in November 2023 following a series of earthquakes. An eruption eventually occurred there on December 18, 2023 with a second eruption on January 14, 2024.

The Meteorological Office said there was no immediate threat to the fishing community of about 3,800 from this most recent eruption.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKz87aZPHnQ

Several communities on the Reykjanes Peninsula were also cut off from sources of heat and hot water after a supply pipeline was swallowed by a river of lava. According to the Associated Press, the Civil Defense agency said lava reached the pipeline that carries heat and hot water from the Svartsengi geothermal power plant. Residents were urged to use electricity and hot water and electricity sparingly, while power plant workers began to lay a new underground water pipe to use as a backup.

The Blue Lagoon uses excess water from the power plant and was closed when the eruption began. According to Iceland's national broadcaster RUV, all guests were safely evacuated and lava spread across the road exiting the spa after the eruption.

Iceland sits over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the boundary between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates. It averages about one volcanic eruption every four to five years. The most disruptive eruption in recent times was the 2010 eruption of the Eyjafjallajokull volcano. Enormous clouds of ash spewed into the atmosphere, disrupting air travel across the Atlantic Ocean for months. Air travel has not been impacted by these most recent eruptions.

[Related: Geologists: We’re not ready for volcanoes.]

The Svartsengi volcanic system on the Reykjanes Peninsula had been dormant for about 800 years. Since 2021, there have been several eruptions. The threat to the roughly 31,000 residents of the peninsula will likely continue as the volcanic system begins to get more active.

“It’s like a tap of water that is now open underneath the ground,” said Grindavik spokeswoman Kristin Maria Birgisdottir, according to The New York Times. Birgisdottir added that unless the volcanic area was “turned off soon,” the peninsula would be seeing “continuous events.”

The two previous eruptions only lasted a few days, but signaled what Iceland’s President Guðni Th. Johannesson called, “a daunting period of upheaval” on the populated Reykjanes Peninsula.

Pictured: Icelandic volcano erupts for third time

Our Foreign Staff

Thu, February 8, 2024

Lava flows across the main road linking Grindavik to the Blue Lagoon spa - Marco Di Marco/AP

A volcanic eruption on the Reykjanes peninsula in south-western Iceland started on Thursday – the third to hit the area since December, authorities have said.

Images showed lava flowing from a fissure, illuminating a plume of smoke rising into the night sky.

The Icelandic Meteorological Office said: “At 5.30 this morning, intense small earthquake activity began north-east of Sylingarfell. About 30 minutes later, an eruption began in the same area.”

It added that, based on an initial assessment from a flyover by the Coast Guard, the fissure was about three kilometres (1.86 miles) long.

Lava illuminated a plume of smoke rising into the night sky - Marco Di Mario/AP

The volcanic eruption started on the Reykjanes peninsula early on Thursday morning - Icelandic Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management/AFP

It happened in the same area as previous eruptions on Dec 18 and Jan 14, near the fishing village of Grindavik, which had been evacuated.

Iceland is home to over 30 active volcano systems, the highest number in Europe. It straddles the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a crack in the ocean floor separating the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates.

Lava flow has spilled onto roads near the famous Blue Lagoon - MARCO DI MARCO/AP

Until March 2021, the Reykjanes peninsula in Iceland had not experienced an eruption for eight centuries.

Fresh eruptions occurred in August 2022, and in July and December last year, leading volcanologists to say it was probably the start of a new era of activity in the region.