Why Can’t the US Get the Giant, Bloodsucking Health Insurance Tick off Its Back?

As with many problems in American life, it largely comes down to two factors: the legacy of white supremacy and corporate profits.

Thom Hartmann

Dec 28, 2024

As with many problems in American life, it largely comes down to two factors: the legacy of white supremacy and corporate profits.

Thom Hartmann

Dec 28, 2024

Common Dreams

There’s only one person in a photograph of a recent G7 meeting who represents a country where an illness can destroy an entire family, leaving them bankrupt and homeless, with the repercussions of that sudden fall into poverty echoing down through generations.

Most Americans have no idea that the United States is quite literally the only country in the developed world that doesn’t define healthcare as an absolute right for all of its citizens. That’s it. We’re the only one left.

The United States spends more on “healthcare” than any other country in the world: about 17% of GDP.

Medicare For All, like Canada has, would save American families thousands every year immediately and do away with the 500,000+ annual bankruptcies in this country that happen only because somebody in the family got sick.

Switzerland, Germany, France, Sweden, and Japan all average around 11%, and Canada, Denmark, Belgium, Austria, Norway, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia all come in between 9.3% and 10.5%.

Health insurance premiums right now make up about 22% of all taxable payroll, whereas Medicare For All would run an estimated 10%.

We are literally the only developed country in the world with an entire multi-billion-dollar for-profit industry devoted to parasitically extracting money from us to then turn over to healthcare providers on our behalf. The for-profit health insurance industry has attached itself to us like a giant, bloodsucking tick.

And it’s not like we haven’t tried.

Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Jack Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson all proposed and made an effort to bring a national healthcare system to the United States. Here’s one example really worth watching where President Kennedy is pushing a single-payer system (as opposed to Britain’s “socialist” model):

They all failed, and when I did a deep dive into the topic two years ago for my book The Hidden History of American Healthcare I found two major barriers to our removing that tick from our backs.

The early opposition, more than 100 years ago, to a national healthcare system came from Southern white congressmen (they were all men) and senators who didn’t want even the possibility that Black people could benefit, health-wise, from white people’s tax dollars. (This thinking apparently still motivates many white Southern politicians.)

The leader of that healthcare-opposition movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a German immigrant named Frederick Hoffman, as I mentioned in a recent newsletter. Hoffman was a senior executive for the Prudential Insurance Company, and wrote several books about the racial inferiority of Black people, a topic he traveled the country lecturing about.

His most well-known book was titled Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro. It became a major best-seller across America when it was first published for the American Economic Association by the Macmillan Company in 1896, the same year the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision legally turned the entire U.S. into an apartheid state.

Hoffman taught that Black people, in the absence of slavery, were so physically and intellectually inferior to whites that if they were simply deprived of healthcare the entire race would die out in a few generations. Denying healthcare to Black people, he said, would solve the “race problem” in America.

Southern politicians quoted Hoffman at length, he was invited to speak before Congress, and was hailed as a pioneer in the field of “scientific racism.” Race Traits was one of the most influential books of its era.

By the 1920s, the insurance company he was a vice president of was moving from life insurance into the health insurance field, which brought an added incentive to lobby hard against any sort of a national healthcare plan.

Which brings us to the second reason America has no national healthcare system: profits.

“Dollar” Bill McGuire, a recent CEO of America’s largest health insurer, UnitedHealth, made about $1.5 billion dollars during his time with that company. To avoid prosecution in 2007 he had to cough up $468 million, but still walked away a billionaire. Stephen J Hemsley, his successor, made off with around half a billion.

And that’s just one of multiple giant insurance companies feeding at the trough of your healthcare needs.

Much of that money, and the pay for the multiple senior executives at that and other insurance companies who make over $1 million a year, came from saying “No!” to people who file claims for payment of their healthcare costs.

This became so painful for Cigna Vice President Wendell Potter that he resigned in disgust after a teenager he knew was denied payment for a transplant and died. He then wrote a brilliant book about his experience in the industry: Deadly Spin: An Insurance Company Insider Speaks Out on How Corporate PR Is Killing Healthcare and Deceiving Americans.

Companies offering such “primary” health insurance simply don’t exist (or are tiny) in almost every other developed country in the world. Mostly, where they do exist, they serve wealthier people looking for “extras” beyond the national system, like luxury hospital suites or air ambulances when overseas. (Switzerland is the outlier with exclusively private insurance, but it’s subsidized, mandatory, and nonprofit.)

If Americans don’t know this, they intuit it.

In the 2020 election there were quite a few issues on statewide ballots around the country. Only three of them outpolled President Joe Biden’s win, and expanding Medicaid to cover everybody was at the top of that list. (The other two were raising the minimum wage and legalizing pot.)

The last successful effort to provide government funded, single-payer healthcare insurance was when Lyndon Johnson passed Medicare and Medicaid (both single-payer systems) in the 1960s. It was a hell of an effort, but the health insurance industry was then a tiny fraction of its current size.

In 1978, when conservatives on the Supreme Court legalized corporations owning politicians with their Buckley v Belotti decision (written by Justice Louis Powell of “Powell Memo” fame), they made the entire process of replacing a profitable industry with government-funded programs like single-payer vastly more difficult, regardless of how much good they may do for the citizens of the nation.

The court then doubled-down on that decision in 2010, when the all-conservative vote on Citizens United cemented the power of billionaires and giant corporations to own politicians and even write and influence legislation and the legislative process.

Medicare For All, like Canada has, would save American families thousands every year immediately and do away with the 500,000+ annual bankruptcies in this country that happen only because somebody in the family got sick. But it would kill the billions every week in profits of the half-dozen corporate giants that dominate the health insurance industry.

This won’t be happening with a billionaire in the White House, but if we want to bring America into the 21st century with the next administration, we need to begin working, planning, and waking up voters now.

It’ll be a big lift: Keep it on your radar and pass it along.

There’s only one person in a photograph of a recent G7 meeting who represents a country where an illness can destroy an entire family, leaving them bankrupt and homeless, with the repercussions of that sudden fall into poverty echoing down through generations.

Most Americans have no idea that the United States is quite literally the only country in the developed world that doesn’t define healthcare as an absolute right for all of its citizens. That’s it. We’re the only one left.

The United States spends more on “healthcare” than any other country in the world: about 17% of GDP.

Medicare For All, like Canada has, would save American families thousands every year immediately and do away with the 500,000+ annual bankruptcies in this country that happen only because somebody in the family got sick.

Switzerland, Germany, France, Sweden, and Japan all average around 11%, and Canada, Denmark, Belgium, Austria, Norway, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia all come in between 9.3% and 10.5%.

Health insurance premiums right now make up about 22% of all taxable payroll, whereas Medicare For All would run an estimated 10%.

We are literally the only developed country in the world with an entire multi-billion-dollar for-profit industry devoted to parasitically extracting money from us to then turn over to healthcare providers on our behalf. The for-profit health insurance industry has attached itself to us like a giant, bloodsucking tick.

And it’s not like we haven’t tried.

Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Jack Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson all proposed and made an effort to bring a national healthcare system to the United States. Here’s one example really worth watching where President Kennedy is pushing a single-payer system (as opposed to Britain’s “socialist” model):

They all failed, and when I did a deep dive into the topic two years ago for my book The Hidden History of American Healthcare I found two major barriers to our removing that tick from our backs.

The early opposition, more than 100 years ago, to a national healthcare system came from Southern white congressmen (they were all men) and senators who didn’t want even the possibility that Black people could benefit, health-wise, from white people’s tax dollars. (This thinking apparently still motivates many white Southern politicians.)

The leader of that healthcare-opposition movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a German immigrant named Frederick Hoffman, as I mentioned in a recent newsletter. Hoffman was a senior executive for the Prudential Insurance Company, and wrote several books about the racial inferiority of Black people, a topic he traveled the country lecturing about.

His most well-known book was titled Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro. It became a major best-seller across America when it was first published for the American Economic Association by the Macmillan Company in 1896, the same year the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision legally turned the entire U.S. into an apartheid state.

Hoffman taught that Black people, in the absence of slavery, were so physically and intellectually inferior to whites that if they were simply deprived of healthcare the entire race would die out in a few generations. Denying healthcare to Black people, he said, would solve the “race problem” in America.

Southern politicians quoted Hoffman at length, he was invited to speak before Congress, and was hailed as a pioneer in the field of “scientific racism.” Race Traits was one of the most influential books of its era.

By the 1920s, the insurance company he was a vice president of was moving from life insurance into the health insurance field, which brought an added incentive to lobby hard against any sort of a national healthcare plan.

Which brings us to the second reason America has no national healthcare system: profits.

“Dollar” Bill McGuire, a recent CEO of America’s largest health insurer, UnitedHealth, made about $1.5 billion dollars during his time with that company. To avoid prosecution in 2007 he had to cough up $468 million, but still walked away a billionaire. Stephen J Hemsley, his successor, made off with around half a billion.

And that’s just one of multiple giant insurance companies feeding at the trough of your healthcare needs.

Much of that money, and the pay for the multiple senior executives at that and other insurance companies who make over $1 million a year, came from saying “No!” to people who file claims for payment of their healthcare costs.

This became so painful for Cigna Vice President Wendell Potter that he resigned in disgust after a teenager he knew was denied payment for a transplant and died. He then wrote a brilliant book about his experience in the industry: Deadly Spin: An Insurance Company Insider Speaks Out on How Corporate PR Is Killing Healthcare and Deceiving Americans.

Companies offering such “primary” health insurance simply don’t exist (or are tiny) in almost every other developed country in the world. Mostly, where they do exist, they serve wealthier people looking for “extras” beyond the national system, like luxury hospital suites or air ambulances when overseas. (Switzerland is the outlier with exclusively private insurance, but it’s subsidized, mandatory, and nonprofit.)

If Americans don’t know this, they intuit it.

In the 2020 election there were quite a few issues on statewide ballots around the country. Only three of them outpolled President Joe Biden’s win, and expanding Medicaid to cover everybody was at the top of that list. (The other two were raising the minimum wage and legalizing pot.)

The last successful effort to provide government funded, single-payer healthcare insurance was when Lyndon Johnson passed Medicare and Medicaid (both single-payer systems) in the 1960s. It was a hell of an effort, but the health insurance industry was then a tiny fraction of its current size.

In 1978, when conservatives on the Supreme Court legalized corporations owning politicians with their Buckley v Belotti decision (written by Justice Louis Powell of “Powell Memo” fame), they made the entire process of replacing a profitable industry with government-funded programs like single-payer vastly more difficult, regardless of how much good they may do for the citizens of the nation.

The court then doubled-down on that decision in 2010, when the all-conservative vote on Citizens United cemented the power of billionaires and giant corporations to own politicians and even write and influence legislation and the legislative process.

Medicare For All, like Canada has, would save American families thousands every year immediately and do away with the 500,000+ annual bankruptcies in this country that happen only because somebody in the family got sick. But it would kill the billions every week in profits of the half-dozen corporate giants that dominate the health insurance industry.

This won’t be happening with a billionaire in the White House, but if we want to bring America into the 21st century with the next administration, we need to begin working, planning, and waking up voters now.

It’ll be a big lift: Keep it on your radar and pass it along.

Lynn Parramore, Institute for New Economic Thinking

December 28, 2024

Photo by Geoffrey Moffett on Unsplash

In the past few weeks, one thing has become crystal clear in America: The public outrage after the assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson exposed a seething fury over the health insurance racket. No amount of media finger-wagging at public perversity or partisan attempts to frame Luigi Mangione’s act as a statement from the left or right can hide the reality: The people, from all sides, are livid about the healthcare system—and with good reason.

In the 21st century, Americans have expressed their view that healthcare is deteriorating, not advancing. For example, according to recent Gallup polls, respondents’ satisfaction with the quality of healthcare has reached its lowest level since 2001. Key point: Americans in those polls “rate healthcare coverage in the U.S. even more negatively than they rate quality.”

Coverage is the core failure, driven by the insurance industry’s profit-first approach to denying care.

It’s a textbook case of “market failure.” Instead of healthy competition lowering prices and improving services, what we have is an oligopoly that drives up costs and leaves millions uninsured.

So here we are, regardless of politicians’ rosy narratives or avoidance of the topic. Politicians on both sides of the aisle should be motivated to take on this scandalous state of affairs, but, as journalist Ken Klippenstein pointed out, presidential nominees Kamala Harris and Donald Trump barely acknowledged healthcare, mentioning it only twice, between them, in their convention speeches. “This is the first election in my adult memory that I can recall healthcare not being at the center of the debate,” Klippenstein remarked, recalling Biden’s 2020 nod to the public option and Bernie Sanders’ strong calls for universal healthcare in 2016.

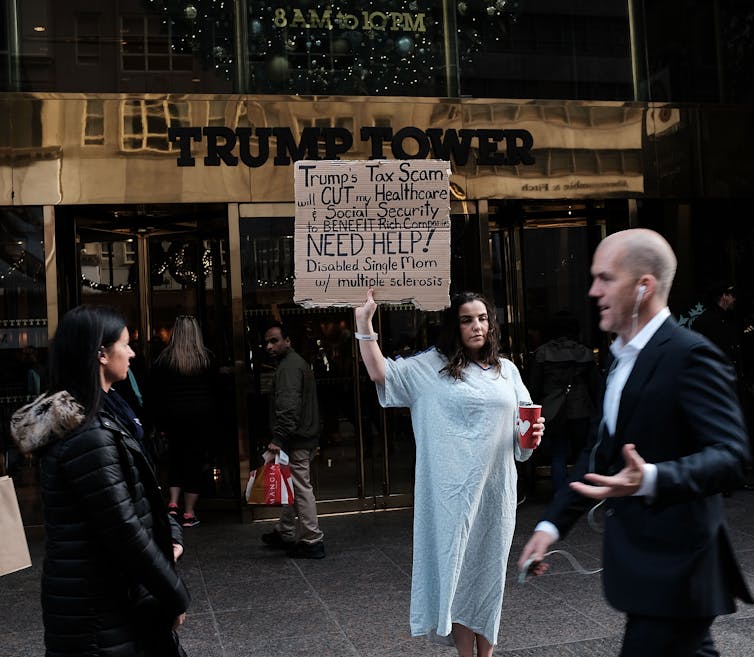

Meanwhile, Americans are crushed by skyrocketing premiums, crippling medical debt, and denial of care that devastates millions of lives. It should be no surprise that frustration has reached a boiling point, igniting a fierce, widespread demand for real, systemic change. Ordinary people are clear that insurance companies don’t exist to protect their health, but to protect and maximize profits for shareholders.

Economist William Lazonick points out that we have every right to expect quality at a fair price, noting that a good health insurance policy should ensure accessible care with the insurer covering the costs—something a single-payer system could deliver. “A for-profit (business-sector) insurer such as UnitedHealthcare could make a profit by offering high-quality insurance,” Lazonick told the Institute for New Economic Thinking, “but they have chosen a business model that seeks to make money by denying as many claims as possible, delaying the payment of claims that they cannot avoid paying, and defending their positions in the courts, if need be.”

This is capitalism run amok.

And the profits are rolling in. Lazonick notes that in 2023, UnitedHealthcare enjoyed an operating profit margin of 8% on revenues of an eye-popping $281.4 billion, insuring 52,750,000 people, which equals revenues (premiums) of $5,334 per insured. The insured, meanwhile, pay not only the premiums, but deductibles, copays, and things like surprise billing. He argues that while the cost of medical care is artificially inflated, health insurers strategize to keep costs in check by enrolling young, healthy people—a windfall provided by the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, which forced consumers into the system while allowing insurers to keep operating as usual, engaging in their profit-maximizing schemes. In his view, the inflated costs of medical care are partly thanks to financialization—a process where healthcare companies prioritize financial strategies like stock buybacks and dividend payouts over actually improving patient care, investing in useful innovations, or lowering premiums.

Alongside his colleague Oner Tulum, Lazonick has shown that the biggest health insurance companies have been on a stock buyback binge, padding their profits and lining the pockets of executives and shareholders: classic Wall Street greed in action. They note that of the top four companies by revenues over the most recent decade, UnitedHealth, CVS Health, Elevance, and Cigna, average annual buybacks were a stunning $3.7 billion. “Ultimately, the manipulative boosts that these buybacks give to the health insurers’ stock prices come out of the pockets of U.S. households in the form of higher insurance premiums,” they write.

It’s easy to see why health insurance executives are obsessed with stock buybacks. Lazonick and Tulum point out that from 2000 to 2017, Stephen J. Helmsley, the CEO of UnitedHealth Group, raked in an annual average of $37.3 million—86% of it coming from stock-based compensation. His successor, Andrew Witty, wasn’t exactly slumming it either, pulling in $17 million a year (79% stock-based) between 2018 and 2023. And then there’s the assassinated Brian Thompson, former CEO of the UnitedHealth subsidiary UnitedHealthcare, who bagged $9.5 million a year (73% stock-based) from 2021 to 2023. It’s a deadly scam, to be sure—inflate the stock price with buybacks, fatten the paychecks for executives (not rank-and-file employees), and deny patients the care they need.

Lazonick observes that the more profits that UnitedHealth Group makes, the more extra cash is available to distribute to shareholders as dividends and buybacks, “and, generally, the higher the stock price, the potential for higher top executive pay.” The unpleasant reality, according to him, is that “given UHC’s predatory business model, Thompson was incentivized by his stock-based pay to rip off customers, and he ascended to the United Healthcare CEO position because he was good at it.”

Perhaps this helps explain why many Americans are not exactly mourning his passing.

The roots of this mess trace back to the neoliberal, market-driven ideology that underpins the system. Neoclassical economics, the theory behind this philosophy, is all about maximizing profit and trusting the market to sort things out—like some magical invisible hand. In reality, it’s a blueprint for inequality: The rich, like insurance CEOS, get richer, and everyone else is subject to exploitation. Healthcare is a perfect example of why this system doesn’t work. When you turn human health into a business, where access is determined by how much you can pay, only the wealthy can count on top-notch, reliably available care. The fundamental contradiction at the heart of the U.S. system is simple: health is treated as a commodity, not a human right.

This current system make sense to the economists still clinging to their outdated, flawed neoclassical principles, but for regular folks? It’s crystal clear: our system is untenable.

The myth that the U.S. health insurance system runs efficiently in a competitive market is just that—a myth. In reality, a handful of for-profit insurers dominate, focused not on providing care, but on extracting profits. It’s a textbook case of “market failure.” Instead of healthy competition lowering prices and improving services, what we have is an oligopoly that drives up costs and leaves millions uninsured. Let’s go over three examples of this failure.

1. Information Asymmetry: In a real competitive market, you’d have clear, straightforward information to make good choices. But in the U.S. health insurance system? Not happening. Insurers deliberately obscure policy details, leaving you to guess the true costs and coverage—even the percentage of claims denied. This gives them all the power while you’re stuck with confusing, impenetrable contracts. They know exactly what they’re doing—and it’s not about helping you.

Say you’re self-employed and stuck buying private insurance on the Health Insurance Marketplace. You don’t qualify for subsidies, so you figure the best you can do is a silver plan with a $1,000 monthly premium. It’s steep, but at least it lists a $45 co-pay for an in-network doctor visit—and it’s got to be in-network because the plan won’t cover a dime of out-of-network care. You sign up for the plan, and then you go to the doctor for a respiratory infection. Surprise! You’re hit with a $200 bill. Why? Because co-pays only apply after you meet your $2,200 deductible—that was in the fine print.

At this point, avoiding the doctor sounds like the best plan.

But wait, isn’t the Health Insurance Marketplace a government-driven system? How could it be so unfair and deceptive? Well, it isn’t exactly a government-driven system. The Marketplace is government-run in name, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, with the feds running HealthCare.gov—but let’s be clear: It’s controlled by private insurers. The government sets some rules, but the real power lies with for-profit companies pulling the strings. What’s sold as a consumer-friendly system is really just a cash cow for the insurance industry.

2. Adverse Selection: Let’s go back to that self-employed person hit with a $200 doctor bill. The next time they get sick, they decide to skip the doctor—why risk a bigger bill? The insurance companies love this—they don’t have to pay a thing while you must keep paying your premium. This is adverse selection in action. Healthy people forgo care to save money, while the sick are stuck with costly plans. Insurers raise premiums, pushing even more people out of the system. The result? A vicious cycle where prices keep climbing, and care becomes harder to access.

3. Externalities: The U.S. health insurance system’s failure to provide universal coverage creates what economists call “negative externalities.” Our self-employed person who didn’t go to the doctor to save money has ended up in the emergency room, where the costs quickly balloon. What started as a simple issue becomes a preventable hospitalization, driving up healthcare costs for everyone and straining public health resources. These added costs don’t just hit the individual—they’re a drag on society as a whole, with taxpayers and the healthcare system picking up the tab. And on top of it all, the person has missed work and spread their illness to others, amplifying both the social and economic damage.

If you want to see information asymmetry, adverse selection, and externalities really come together, look no further than Medicare Advantage, which economist Eileen Appelbaum plainly calls a “scam”—and one that is liable to expand under Trump’s second term.

As Appelbaum explains, Medicare Advantage is neither Medicare nor is it to anyone’s advantage except insurance companies.

Medicare Advantage is actually a private insurance program that is sold as an alternative to traditional Medicare, advertised to combine hospital, medical, and often prescription coverage, and offer perks such as gym membership coverage. It was originally created in 1997 as part of the Balanced Budget Act under President Bill Clinton to allow private insurers to manage Medicare benefits with a focus on cost control and efficiency.

Proponents claim that privately-run Medicare Advantage plans, which now enroll over half of all people eligible for Medicare, offer good value, but Appelbaum notes this is only the case if you manage not to get a chronic condition—you’d better not get cancer or get too sick.

A 2017 report by the Government Accountability Office found that sicker patients not only don’t benefit from these plans, they are worse off than they would be under Medicare, barred from access to their preferred doctors and hospitals.

Appelbaum notes that the Medicare Advantage program is really a patchwork of private plans run by for-profit companies that rake in billions in taxpayer subsidies while finding new ways to deny care—like endless preauthorizations and rejecting expensive post-acute treatments. Unlike traditional Medicare, which directly pays for services, these private insurers are paid per subscriber, boosting their profits by upcoding and cherry-picking healthier clients. The result: Taxpayers lose $88 to $140 billion a year. But what a boon to the insurers: Appelbaum notes that they now make more from Medicare Advantage than from all their other products combined.

In a 2023 report, Appelbaum and her colleagues noted that recent evidence reveals that Medicare Advantage insurers have been denying claims at unreasonably high rates, particularly for home health services. They point to a 2022 report from the Office of the Inspector General for the U.S. Health and Human Services, which found that in 2019, 13% of prior authorization requests for medically necessary care, including post-acute home health services, were denied despite meeting Medicare coverage rules. These services would have been covered under traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Though some denied requests were later approved, the delays jeopardized patients’ health and imposed administrative burdens. On top of that, a 2021 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services study showed that over 2 million of 35 million prior authorization requests were denied, with only 11% appealed. Of those, 82% of appeals were successful, highlighting a high rate of incorrect denials.

Appelbaum points out that, despite the similar names, Medicare and Medicare Advantage are worlds apart. Medicare is a trusted public program, while Medicare Advantage is really just private insurance that’s marketed to look like the real thing, luring people in with misleading ads and false promises. The goal of Medicare Advantage supporters is to replace traditional, publicly funded Medicare with private, for-profit insurers—pushing for market competition and cost-cutting at the expense of direct, government-provided healthcare. It’s a prime example of what happens when neoclassical economics gets its way.

“It goes back to the Affordable Care Act,” she explained in a conversation with the Institute for New Economic Thinking. “The ACA introduced many beneficial reforms, but it also required Medicare to experiment with Medicare Advantage plans as part of a broader push for “value-based” care, where providers are going to be incentivized to skimp on your care.” She stressed that this isn’t just financially harmful for patients—it can be deadly. It’s not merely about denying care; it’s about using delaying tactics that put lives at risk: “Widespread delay is a serious problem—when someone has cancer, two weeks of delays waiting for coverage to be approved can be deadly.”

The reality is that with value-based care, providers are rewarded for reducing costs, rather than being paid for the volume of services they deliver, which can encourage cost-cutting measures that potentially compromise care quality.

And as to that much-touted competition that neoclassical economists insist will lower costs and boost efficiency among insurers—good luck finding an example of that. The administrative costs of private insurers are staggering compared to single-payer systems. According to a 2018 study in The Lancet, the U.S. spends 8% of total national health expenditures on activities related to planning, regulating, and managing health systems and services, compared to an average of only 3% spent in single-payer systems. The excess administrative burden in the U.S. is a direct consequence of having to navigate a fragmented system with multiple insurers, each with its own rules, coverage policies, and approval processes.

Beyond the outrageous administrative costs, the U.S. healthcare system’s reliance on employer-based insurance is a relic of 20th-century policy decisions that are downright outdated in today’s gig economy. It ties access to care to your job, effectively locking out millions of gig and part-time workers, freelancers, and the unemployed. The notion that people can “shop around” for insurance plans like they’re picking a toaster is absurd when the stakes are life and death.

The exorbitant cost of this flawed approach to healthcare is borne by society—through higher overall health spending, worse outcomes, and a public system buckling under the weight of the uninsured and underinsured. The system doesn’t just fail to provide equitable care; it deepens social and economic inequality. Health should be a public good, with care guaranteed for all—regardless of income, job, or pre-existing conditions.

Many argue that the solution isn’t patching the system with small reforms but rethinking it entirely—or, as documentary maker Michael Moore recently put it, “Throw this entire system in the trash.” That means embracing models like single-payer, where the state ensures health for all and care is based on need, not profit.

Until the U.S. abandons its current insurance model, we’ll remain stuck with a system that enriches a few while exploiting the many—and the many are well and truly sick of it.

America is ready to say goodbye to the Grinches that operate 365 days a year.

I Got Cancer at 35. The Health Insurance System Delayed My Treatment for Months.

Young adults face rising cancer rates — and barriers to timely interventions.

By Michelle Zacarias , TruthoutPublishedDecember 27, 2024

My gastroenterologist gulped as he read the results of my colonoscopy. The images confirmed what I had already been told: A malignant tumor was blocking nearly the entire pathway of my colon.

I could sense his guilt. After all, he had initially placed me on a two-month waiting list for the procedure — on top of the three months it had taken just to get an appointment with his office.

He spoke carefully, choosing his words with the precision of someone trying to avoid legal fallout. He explained, in the gentlest terms, why he had initially misdiagnosed my symptoms as a possible autoimmune disorder. But by then, I wasn’t angry — I was devastated. Fear and disappointment had long since replaced any sense of outrage. The harsh reality was clear: The U.S. health care system had failed me at nearly every turn.

Since the onset of my symptoms in October 2023, I faced one obstacle after another. My insurance took weeks to authorize urgent referrals, after which I had to wait months for a specialist of their choosing. All the while, my body deteriorated. Diarrhea, bloating, increased gas, irregular stools and constant digestive discomfort became my everyday reality, while I was forced to wait — wait for appointments, wait for diagnoses, wait for someone to take me seriously. Between April 2023 and my diagnosis in June 2023, I lost a whopping 30 pounds, nearly a third of my original weight.

It wasn’t just the colorectal cancer that was killing me — it was the crushing inefficiency, delays and gaps in care that allowed my condition to worsen unchecked. What should have been a straightforward diagnosis and treatment plan became an endless series of frustrations and missed opportunities, with my life hanging in the balance.

It’s Not Just Denied Claims. Insurance Firms Are Hiring Middlemen to Deny Meds.

Lawmakers are looking to break up massive health care conglomerates that manage nearly 80 percent of prescriptions. By Mike Ludwig , Truthout December 14, 2024

Shared frustrations of this sort have manifested in growing anger across the country, particularly in the wake of the shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. While some have expressed support for the alleged suspect, Luigi Mangione, this tragedy underscores a much larger discontent with a health care system that has left millions of Americans feeling helpless and unheard.

It wasn’t just the colorectal cancer that was killing me — it was the crushing inefficiency, delays and gaps in care that allowed my condition to worsen unchecked.

It’s not just about one individual; it’s about an entire system that has failed countless people like me, pushing them to desperate measures. The widespread grief and rage are a testament to how deeply the roots of this crisis run, and how many have suffered in silence, waiting for change that never comes.

An Alarming Shift in Cancer Demographics

In recent years, a concerning trend has emerged: Young people, particularly those under 55, are being diagnosed with cancers once considered predominantly diseases of older adults. From lung and colorectal cancers to breast and thyroid cancers, malignancies traditionally associated with aging are now showing up in younger populations with alarming frequency. Alongside this troubling increase in diagnoses is a parallel crisis: delays in treatment and care due to issues of health care access, insurance coverage and systemic barriers to timely interventions.

Between 1990 and 2019, new cancer cases among younger adults increased by nearly 79 percent worldwide, according to a study published in BMJ Oncology.

In discussing key risk factors driving this alarming rise, the study’s authors pointed to dietary factors, alcohol consumption and tobacco use as the primary contributors to the most common early-onset cancers in 2019. Current tobacco use among U.S. middle and young adults, however, has dropped to its lowest recorded level in 25 years. Research suggests that a wide variety of variables — ranging from environmental factors, including chemical exposure and air and water pollution, to genetic predispositions — are playing an increasingly significant role in the surge of cancer diagnoses among younger adults. These factors, coupled with changes in lifestyle and exposures, could help explain the troubling trend of rising cancer rates in a group once thought to be less vulnerable.

The study also notes a significant uptick in cancer rates, particularly among women and people in their 30s. While cancer remains more common in older adults, the rising numbers in younger populations have raised alarm among health experts, who are grappling with the underlying causes and implications for early detection and treatment.

Researchers are continuing to explore the factors contributing to this trend, including lifestyle changes, environmental exposures and genetic factors.

“I had trained medical doctors tell me, ‘You’re too young to be sick.’”

The increasing burden of cancer in younger adults has already prompted calls for more targeted screening and prevention strategies in this at-risk group. Despite a nearly 50 percent rise in colorectal cancer rates among people under 55 since the 1990s, I faced a nine-month delay in receiving treatment. Being 35, my age didn’t raise enough red flags for doctors to suspect colorectal cancer — especially since the median age of diagnosis is 70 for men and 72 for women, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Even more concerning, my own history with childhood cancer — over 25 years ago — was dismissed by medical professionals as being irrelevant to my symptoms. At one point, I was even told that it was “unlikely” I would develop cancer again so long after remission. The assumption that younger patients are less likely to be at risk for serious conditions like colorectal cancer continues to contribute to dangerous delays from both medical providers and health insurance companies.

Experiences like mine are far from unique. Take A. Baroff, for example, who had to wait two years to undergo surgery for thyroid cancer. Despite her background in medical research, she faced persistent skepticism from health care professionals throughout her ordeal. Her initial symptoms — eye problems, neuropathy, and difficulty breathing and swallowing — were dismissed as “hypochondria” by doctors, delaying her diagnosis and treatment. Unfortunately, stories like Baroff’s highlight the frustrating and often dangerous delays that many cancer patients experience before they finally get the care they need.

“I had trained medical doctors tell me, ‘You’re too young to be sick’,” said Baroff, “and it felt so disheartening that no matter what I said about my own body, I was treated as though I was not right or making up symptoms.” The day she was finally diagnosed, she checked herself into the emergency room, where doctors initially told her swollen lymph nodes were simply a result of a cold. Refusing to leave without answers, she insisted on an ultrasound, and her self-advocacy paid off. That was in January 2020 — just before the world shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the weeks following her diagnosis, Baroff faced another setback: her insurance company dropped her coverage. Having recently returned to California after living in Boston for medical school, she was now confronted with the harsh reality of the state’s overwhelmed health care system. As a result, her thyroid cancer went untreated for more than two years, delayed further by strict hospital lockdowns during the early days of the pandemic. Moving home to be closer to family had unintended consequences, postponing her treatment at a critical time.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients, including Baroff, were told they would need to wait for essential medical procedures as hospitals prioritized more “high-risk” cases. This disruption, compounded by insurance issues and inefficiencies in the health care system, brought into sharp focus the struggles faced by younger people confronting chronic illness for the first time in their lives. For many, the pandemic underscored the vulnerability of a medical system ill-equipped to address their needs in a time of crisis.

The growing cancer crisis among young adults has reignited discussions around systemic health care reform, particularly the push for Medicare for All.

“I was completely in survival mode,” said Baroff of navigating cancer while quarantined. Although she continued to try and reach out to medical experts in her area for second opinions and treatment options, many hospitals were at capacity. “I was pretty isolated and anxious. I think it was just a lot of fear and worry during that time, on top of experiencing [cancer] symptoms.”

In a last-ditch effort, Baroff reached out to a former colleague from her time at Harvard Medical School, who connected her with a specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. In March 2022, she was finally able to schedule surgery in Boston to remove the tumor. Yet her experience serves as a stark reminder of the systemic issues within health care, particularly for young patients, and underscores the critical need for greater empathy and urgency in medical care.

Prescreening: A Barrier to Early Detection and Timely Treatment

For many young people who are diagnosed with cancer, the journey from detection to treatment is far from straightforward. While prescreening programs for older adults are relatively well-established, younger populations often fall through the cracks in the health care system. Screening guidelines for many types of cancer do not typically recommend early checks for those under 50, leaving younger adults without an easy path to early diagnosis.

Rhonda Bulwer was 36 when she first discovered a lump in her right breast. In July 2023, she requested a mammogram, but her age — below the typical threshold for routine screening — delayed the process by a month, despite her family’s history of breast cancer. After undergoing a mammogram, ultrasound and biopsy, Bulwer was diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer in October 2023.

Bulwer chose to participate in a clinical trial, an option recommended by her doctor. However, her insurance company initially denied approval for the experimental treatment due to delays by her health care provider, who did not reach out to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center until just days before the trial was set to begin. This was partly due to holiday scheduling when many medical offices were closed and staff, who already experienced burnout, failed to initiate timely communication.

“I pleaded with insurance for them to appeal,” said Bulwer, “but the time the approval came through, the clinical trial denied me because they wanted to start in early January and I had already missed the deadline.”

True health care justice can only be achieved when all people, regardless of income or background, have access to the care they need without financial or bureaucratic barriers.

When the clinical trial fell through, Bulwer turned to standard treatments — immunotherapy and surgery — delaying her care by another month. She also encountered obstacles in advocating for her needs with her surgeon. To undergo a double mastectomy, she needed approval from both her doctor and her insurance company. While the insurance company agreed to cover the procedure, her doctor hesitated, deeming the surgery on both breasts unnecessary, despite Bulwer’s family history — her grandmother had died from breast cancer-related complications.

Eventually, Bulwer secured approval from her medical team for the surgery, and her insurance agreed to cover most of the cost. She is now recovering and will undergo two more rounds of immunotherapy.

A Call to Address the Health Care Gaps

As we confront this public health crisis, the question remains: What needs to be done to ensure that young adults are given the tools they need to fight — and survive — cancer?

Young adults face rising cancer rates — and barriers to timely interventions.

By Michelle Zacarias , TruthoutPublishedDecember 27, 2024

Michelle documents her treatment journey with a selfie during a 3-hour chemotherapy session in October, 2024.Michelle Zacarias

My gastroenterologist gulped as he read the results of my colonoscopy. The images confirmed what I had already been told: A malignant tumor was blocking nearly the entire pathway of my colon.

I could sense his guilt. After all, he had initially placed me on a two-month waiting list for the procedure — on top of the three months it had taken just to get an appointment with his office.

He spoke carefully, choosing his words with the precision of someone trying to avoid legal fallout. He explained, in the gentlest terms, why he had initially misdiagnosed my symptoms as a possible autoimmune disorder. But by then, I wasn’t angry — I was devastated. Fear and disappointment had long since replaced any sense of outrage. The harsh reality was clear: The U.S. health care system had failed me at nearly every turn.

Since the onset of my symptoms in October 2023, I faced one obstacle after another. My insurance took weeks to authorize urgent referrals, after which I had to wait months for a specialist of their choosing. All the while, my body deteriorated. Diarrhea, bloating, increased gas, irregular stools and constant digestive discomfort became my everyday reality, while I was forced to wait — wait for appointments, wait for diagnoses, wait for someone to take me seriously. Between April 2023 and my diagnosis in June 2023, I lost a whopping 30 pounds, nearly a third of my original weight.

It wasn’t just the colorectal cancer that was killing me — it was the crushing inefficiency, delays and gaps in care that allowed my condition to worsen unchecked. What should have been a straightforward diagnosis and treatment plan became an endless series of frustrations and missed opportunities, with my life hanging in the balance.

It’s Not Just Denied Claims. Insurance Firms Are Hiring Middlemen to Deny Meds.

Lawmakers are looking to break up massive health care conglomerates that manage nearly 80 percent of prescriptions. By Mike Ludwig , Truthout December 14, 2024

Shared frustrations of this sort have manifested in growing anger across the country, particularly in the wake of the shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. While some have expressed support for the alleged suspect, Luigi Mangione, this tragedy underscores a much larger discontent with a health care system that has left millions of Americans feeling helpless and unheard.

It wasn’t just the colorectal cancer that was killing me — it was the crushing inefficiency, delays and gaps in care that allowed my condition to worsen unchecked.

It’s not just about one individual; it’s about an entire system that has failed countless people like me, pushing them to desperate measures. The widespread grief and rage are a testament to how deeply the roots of this crisis run, and how many have suffered in silence, waiting for change that never comes.

An Alarming Shift in Cancer Demographics

In recent years, a concerning trend has emerged: Young people, particularly those under 55, are being diagnosed with cancers once considered predominantly diseases of older adults. From lung and colorectal cancers to breast and thyroid cancers, malignancies traditionally associated with aging are now showing up in younger populations with alarming frequency. Alongside this troubling increase in diagnoses is a parallel crisis: delays in treatment and care due to issues of health care access, insurance coverage and systemic barriers to timely interventions.

Between 1990 and 2019, new cancer cases among younger adults increased by nearly 79 percent worldwide, according to a study published in BMJ Oncology.

In discussing key risk factors driving this alarming rise, the study’s authors pointed to dietary factors, alcohol consumption and tobacco use as the primary contributors to the most common early-onset cancers in 2019. Current tobacco use among U.S. middle and young adults, however, has dropped to its lowest recorded level in 25 years. Research suggests that a wide variety of variables — ranging from environmental factors, including chemical exposure and air and water pollution, to genetic predispositions — are playing an increasingly significant role in the surge of cancer diagnoses among younger adults. These factors, coupled with changes in lifestyle and exposures, could help explain the troubling trend of rising cancer rates in a group once thought to be less vulnerable.

The study also notes a significant uptick in cancer rates, particularly among women and people in their 30s. While cancer remains more common in older adults, the rising numbers in younger populations have raised alarm among health experts, who are grappling with the underlying causes and implications for early detection and treatment.

Researchers are continuing to explore the factors contributing to this trend, including lifestyle changes, environmental exposures and genetic factors.

“I had trained medical doctors tell me, ‘You’re too young to be sick.’”

The increasing burden of cancer in younger adults has already prompted calls for more targeted screening and prevention strategies in this at-risk group. Despite a nearly 50 percent rise in colorectal cancer rates among people under 55 since the 1990s, I faced a nine-month delay in receiving treatment. Being 35, my age didn’t raise enough red flags for doctors to suspect colorectal cancer — especially since the median age of diagnosis is 70 for men and 72 for women, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Even more concerning, my own history with childhood cancer — over 25 years ago — was dismissed by medical professionals as being irrelevant to my symptoms. At one point, I was even told that it was “unlikely” I would develop cancer again so long after remission. The assumption that younger patients are less likely to be at risk for serious conditions like colorectal cancer continues to contribute to dangerous delays from both medical providers and health insurance companies.

Experiences like mine are far from unique. Take A. Baroff, for example, who had to wait two years to undergo surgery for thyroid cancer. Despite her background in medical research, she faced persistent skepticism from health care professionals throughout her ordeal. Her initial symptoms — eye problems, neuropathy, and difficulty breathing and swallowing — were dismissed as “hypochondria” by doctors, delaying her diagnosis and treatment. Unfortunately, stories like Baroff’s highlight the frustrating and often dangerous delays that many cancer patients experience before they finally get the care they need.

“I had trained medical doctors tell me, ‘You’re too young to be sick’,” said Baroff, “and it felt so disheartening that no matter what I said about my own body, I was treated as though I was not right or making up symptoms.” The day she was finally diagnosed, she checked herself into the emergency room, where doctors initially told her swollen lymph nodes were simply a result of a cold. Refusing to leave without answers, she insisted on an ultrasound, and her self-advocacy paid off. That was in January 2020 — just before the world shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the weeks following her diagnosis, Baroff faced another setback: her insurance company dropped her coverage. Having recently returned to California after living in Boston for medical school, she was now confronted with the harsh reality of the state’s overwhelmed health care system. As a result, her thyroid cancer went untreated for more than two years, delayed further by strict hospital lockdowns during the early days of the pandemic. Moving home to be closer to family had unintended consequences, postponing her treatment at a critical time.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients, including Baroff, were told they would need to wait for essential medical procedures as hospitals prioritized more “high-risk” cases. This disruption, compounded by insurance issues and inefficiencies in the health care system, brought into sharp focus the struggles faced by younger people confronting chronic illness for the first time in their lives. For many, the pandemic underscored the vulnerability of a medical system ill-equipped to address their needs in a time of crisis.

The growing cancer crisis among young adults has reignited discussions around systemic health care reform, particularly the push for Medicare for All.

“I was completely in survival mode,” said Baroff of navigating cancer while quarantined. Although she continued to try and reach out to medical experts in her area for second opinions and treatment options, many hospitals were at capacity. “I was pretty isolated and anxious. I think it was just a lot of fear and worry during that time, on top of experiencing [cancer] symptoms.”

In a last-ditch effort, Baroff reached out to a former colleague from her time at Harvard Medical School, who connected her with a specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. In March 2022, she was finally able to schedule surgery in Boston to remove the tumor. Yet her experience serves as a stark reminder of the systemic issues within health care, particularly for young patients, and underscores the critical need for greater empathy and urgency in medical care.

Michelle sits cupping her hands nervously during her first chemotherapy infusion in September, 2024.Michelle Zacarias

Prescreening: A Barrier to Early Detection and Timely Treatment

For many young people who are diagnosed with cancer, the journey from detection to treatment is far from straightforward. While prescreening programs for older adults are relatively well-established, younger populations often fall through the cracks in the health care system. Screening guidelines for many types of cancer do not typically recommend early checks for those under 50, leaving younger adults without an easy path to early diagnosis.

Rhonda Bulwer was 36 when she first discovered a lump in her right breast. In July 2023, she requested a mammogram, but her age — below the typical threshold for routine screening — delayed the process by a month, despite her family’s history of breast cancer. After undergoing a mammogram, ultrasound and biopsy, Bulwer was diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer in October 2023.

Bulwer chose to participate in a clinical trial, an option recommended by her doctor. However, her insurance company initially denied approval for the experimental treatment due to delays by her health care provider, who did not reach out to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center until just days before the trial was set to begin. This was partly due to holiday scheduling when many medical offices were closed and staff, who already experienced burnout, failed to initiate timely communication.

“I pleaded with insurance for them to appeal,” said Bulwer, “but the time the approval came through, the clinical trial denied me because they wanted to start in early January and I had already missed the deadline.”

True health care justice can only be achieved when all people, regardless of income or background, have access to the care they need without financial or bureaucratic barriers.

When the clinical trial fell through, Bulwer turned to standard treatments — immunotherapy and surgery — delaying her care by another month. She also encountered obstacles in advocating for her needs with her surgeon. To undergo a double mastectomy, she needed approval from both her doctor and her insurance company. While the insurance company agreed to cover the procedure, her doctor hesitated, deeming the surgery on both breasts unnecessary, despite Bulwer’s family history — her grandmother had died from breast cancer-related complications.

Eventually, Bulwer secured approval from her medical team for the surgery, and her insurance agreed to cover most of the cost. She is now recovering and will undergo two more rounds of immunotherapy.

A Call to Address the Health Care Gaps

As we confront this public health crisis, the question remains: What needs to be done to ensure that young adults are given the tools they need to fight — and survive — cancer?

Michelle shares a heartfelt embrace with her surgeon, Dr. Carmen Ruiz, after a successful tumor removal surgery in August, 2024.Michelle Zacarias

The rise in cancer diagnoses among young people calls for a radical reevaluation of health care policies. First and foremost, there needs to be a national conversation about expanding and standardizing prescreening programs for younger adults. Many medical organizations, including the American Cancer Society, are already advocating for earlier screening for colorectal cancer, for instance, with recommendations suggesting that individuals with no family history of cancer should begin regular screenings at age 45, rather than 50.

Compounding this issue is the reality of health care access. Many young adults are navigating a health care landscape that is dominated by private insurance, which can be prohibitively expensive, particularly for those in low-wage or gig economy jobs without employer-sponsored plans. High deductibles, copayments and gaps in coverage often prevent people from seeking timely care, and insurance companies may delay or deny life-saving treatments in favor of lower-cost alternatives.

In the United States, health care coverage disparities have long been a source of systemic inequality. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) did expand coverage for many young people, but that coverage may be at risk. If Republicans allow the enhanced ACA subsidies to expire at the end of 2025, millions of Americans who rely on financial assistance to buy health coverage could lose their insurance.

I often reflect on the conversations I’ve had with fellow cancer patients like Baroff and Bulwer, who share similar stories of gaslighting and dehumanization within medical institutions that are supposed to save our lives. During our interview, Baroff said something that deeply resonated: “When people are at their most vulnerable, they’re not going to be their best selves.” This is why we rely so heavily on the expertise and empathy of doctors and medical practitioners to guide us through such a deeply traumatic journey.

Ultimately, that journey is impossible without systemic reform at every level — from the hospitals where we receive care to the pre-screenings that insurance companies often block.

The growing cancer crisis among young adults has reignited discussions around systemic health care reform, particularly the push for Medicare for All. As cancer diagnoses in younger populations rise, especially those under 45, advocates of universal health care have been vocal in connecting the dots between access to timely, life-saving care and the broader failures of the current health care system.

Medicare for All advocates have argued that comprehensive, universal coverage is necessary to address not just the immediate needs of patients but also the structural inequities that exacerbate health disparities — such as the burden of high insurance premiums, rising co-pays, and the troubling trend of insurance companies denying or delaying coverage for necessary treatments or pre-screenings. The current cancer crisis among young adults has brought this conversation to the forefront, drawing attention to how the health care system often fails to protect the most vulnerable, and underscoring the necessity of a more equitable, efficient model like Medicare for All.

Though the Medicare for All movement has been active for years, often under the radar, the urgency of the current moment has brought it into sharper focus.

Researchers and medical advocates have used the surge in cancer diagnoses to make a compelling case for the need to overhaul a health care system that routinely privileges profit over patients’ well-being. The push for systemic reform has highlighted how structural barriers — from high deductibles and restricted access to preventative screenings to the increasingly monopolized hospital systems — contribute to late-stage cancer diagnoses and worsened survival rates. Their calls for policy change underscore that true health care justice can only be achieved when all people, regardless of income or background, have access to the care they need without financial or bureaucratic barriers.

To make a meaningful difference, we need not only comprehensive health care reform but also a cultural shift in how cancer is understood and treated in younger patients. Without these changes, countless lives will continue to be lost to a disease that could have been detected and treated much earlier.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Michelle Zacarias

Michelle Zacarias (she/her) is a queer Latina award-winning journalist, storyteller, and two-time cancer survivor. Born and raised in Chicago, Michelle currently resides in Southern California. As a CALÓ News reporter and UC Berkeley Local News Fellow, she covers health care, politics, equity and topics pertaining to state-sanctioned violence. Michelle writes the candid column Sin Pena, where she shares her journey navigating colorectal cancer and confronting health care inequities. Her work has appeared in Windy City Times, Teen Vogue, City Bureau, The Triibe, and more. In 2018, she won the Saul Miller Excellence in Journalism Award and was a 2024 finalist for the LA Press Club’s SoCal Journalism Award in Political Commentary.

The rise in cancer diagnoses among young people calls for a radical reevaluation of health care policies. First and foremost, there needs to be a national conversation about expanding and standardizing prescreening programs for younger adults. Many medical organizations, including the American Cancer Society, are already advocating for earlier screening for colorectal cancer, for instance, with recommendations suggesting that individuals with no family history of cancer should begin regular screenings at age 45, rather than 50.

Compounding this issue is the reality of health care access. Many young adults are navigating a health care landscape that is dominated by private insurance, which can be prohibitively expensive, particularly for those in low-wage or gig economy jobs without employer-sponsored plans. High deductibles, copayments and gaps in coverage often prevent people from seeking timely care, and insurance companies may delay or deny life-saving treatments in favor of lower-cost alternatives.

In the United States, health care coverage disparities have long been a source of systemic inequality. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) did expand coverage for many young people, but that coverage may be at risk. If Republicans allow the enhanced ACA subsidies to expire at the end of 2025, millions of Americans who rely on financial assistance to buy health coverage could lose their insurance.

I often reflect on the conversations I’ve had with fellow cancer patients like Baroff and Bulwer, who share similar stories of gaslighting and dehumanization within medical institutions that are supposed to save our lives. During our interview, Baroff said something that deeply resonated: “When people are at their most vulnerable, they’re not going to be their best selves.” This is why we rely so heavily on the expertise and empathy of doctors and medical practitioners to guide us through such a deeply traumatic journey.

Ultimately, that journey is impossible without systemic reform at every level — from the hospitals where we receive care to the pre-screenings that insurance companies often block.

The growing cancer crisis among young adults has reignited discussions around systemic health care reform, particularly the push for Medicare for All. As cancer diagnoses in younger populations rise, especially those under 45, advocates of universal health care have been vocal in connecting the dots between access to timely, life-saving care and the broader failures of the current health care system.

Medicare for All advocates have argued that comprehensive, universal coverage is necessary to address not just the immediate needs of patients but also the structural inequities that exacerbate health disparities — such as the burden of high insurance premiums, rising co-pays, and the troubling trend of insurance companies denying or delaying coverage for necessary treatments or pre-screenings. The current cancer crisis among young adults has brought this conversation to the forefront, drawing attention to how the health care system often fails to protect the most vulnerable, and underscoring the necessity of a more equitable, efficient model like Medicare for All.

Though the Medicare for All movement has been active for years, often under the radar, the urgency of the current moment has brought it into sharper focus.

Researchers and medical advocates have used the surge in cancer diagnoses to make a compelling case for the need to overhaul a health care system that routinely privileges profit over patients’ well-being. The push for systemic reform has highlighted how structural barriers — from high deductibles and restricted access to preventative screenings to the increasingly monopolized hospital systems — contribute to late-stage cancer diagnoses and worsened survival rates. Their calls for policy change underscore that true health care justice can only be achieved when all people, regardless of income or background, have access to the care they need without financial or bureaucratic barriers.

To make a meaningful difference, we need not only comprehensive health care reform but also a cultural shift in how cancer is understood and treated in younger patients. Without these changes, countless lives will continue to be lost to a disease that could have been detected and treated much earlier.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Michelle Zacarias

Michelle Zacarias (she/her) is a queer Latina award-winning journalist, storyteller, and two-time cancer survivor. Born and raised in Chicago, Michelle currently resides in Southern California. As a CALÓ News reporter and UC Berkeley Local News Fellow, she covers health care, politics, equity and topics pertaining to state-sanctioned violence. Michelle writes the candid column Sin Pena, where she shares her journey navigating colorectal cancer and confronting health care inequities. Her work has appeared in Windy City Times, Teen Vogue, City Bureau, The Triibe, and more. In 2018, she won the Saul Miller Excellence in Journalism Award and was a 2024 finalist for the LA Press Club’s SoCal Journalism Award in Political Commentary.

.JPG)