The Morbidly Rich Have Killed the American Dream

The promise that if you work hard and play by the rules, you will get ahead, or if you don’t, surely your children will, was broken long ago. But there’s a way to turn this around.

George, who is homeless, panhandles along a street in Lawrence Massachusetts. Lawrence, once one of America’s great manufacturing cities with immigrants from around the world coming to work in its textile and wool processing mills, has struggled to find its economic base since the decline of manufacturing.

(Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

John Miller

Dec 26, 2025

If Americans’ hopes of getting ahead have dimmed, as the Wall Street Journal reports yet again, it could only be because the lid of the coffin in which the “American Dream” was long ago laid to rest has finally been sealed shut.

The promise that if you work hard and play by the rules, you will get ahead, or if you don’t, surely your children will, was broken long ago. And today’s economic hardships have left young adults distinctly worse off than their parents, and especially their grandparents.

Global System ‘Rigged for the Wealthy’ Delivers World With ‘More Billionaires Than Ever’

This long decline has stripped away much of what there was of U.S. social mobility, which never did measure up to its mythic renderings. Let’s look closely at what the economic evidence, compiled in many meticulous studies, tells us about what passed for the American Dream, its demise, and what it would take to make its promised social mobility a reality.

The Long Decline

For at least two decades now, the Wall Street Journal has reported the dimming prospects of Americans getting ahead, each time with apparent surprise. In 2005, David Wessell presented the mounting evidence that had punctured the myth that social mobility is what distinguishes the United States from other advanced capitalist societies. A study conducted by economist Miles Corak put the lie to that claim. Corak found that the United States and United Kingdom were “the least mobile” societies among the rich countries he studied. In those two countries, children’s income increased the least from that of their parents. By that measure, social mobility in Germany was 1.5 times greater than social mobility in the United States; Canadian social mobility was almost 2.5 times greater than U.S. social mobility; and in Denmark, social mobility was three times greater than in the United States.

That U.S. social mobility lagged far behind the myth of America as a land of opportunity was probably no surprise to those who populated the work-a-day world of the U.S. economy in 2005. Corrected for inflation, the weekly wages of nonsupervisory workers in 2006 stood at just 85% of what they had been in 1973, over three decades earlier. An unrelenting increase in inequality had plagued the U.S. economy since the late 1970s. A Brookings Institution study of economic mobility published in 2007 reported that from 1979 to 2004, corrected for inflation, the after-tax income of the richest 1% of households increased 176% and increased 69% for the top one-fifth of households—but just 9% for the poorest fifth of households.

The Economist also found this increasing inequality worrisome. But its 2006 article, “Inequality and the American Dream,” assured readers that while greater inequality lengthens the ladder that spans the distance from poor to rich, it was “fine” if it had “rungs.” That is, widening inequality can be tolerated as long as “everybody has an opportunity to climb up through the system.”

Definitive proof that increasing U.S. inequality had not provided the rungs necessary to sustain social mobility came a decade later.

The American Dream Is Down for the Count

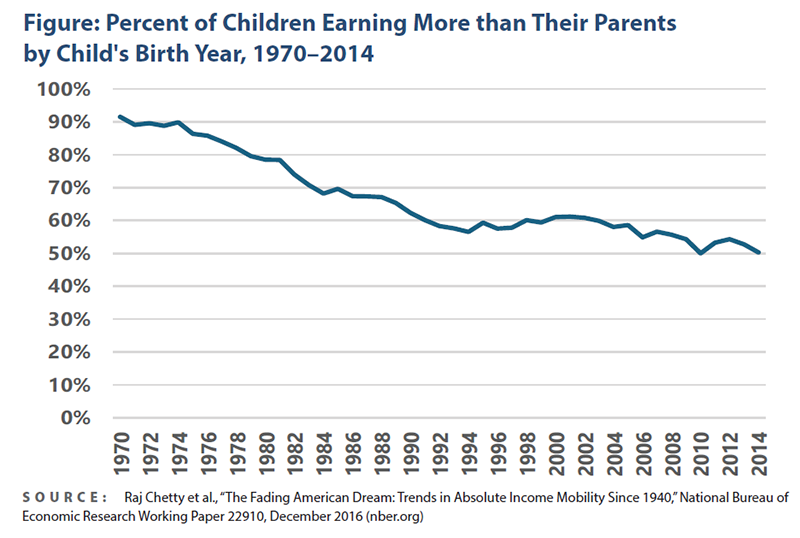

In late 2016, economist Raj Chetty and his multiple coauthors published their study, “The Fading American Dream: Trends.” They documented a sharp decline in mobility in the U.S economy over nearly half a century. In 1970, the household income (corrected for inflation) of 92% of 30-year-olds (born in 1940) exceeded their parents’ income at the same age. By 1990, just three-fifths (60.1%) of 30-year-olds (born in 1960) lived in households with more income than their parents earned at age 30. By 2014, that figure had dropped to nearly one-half. Only 50.3% of children born in 1984 earned more than their parents at age 30. (The figure below depicts this unrelenting decline in social mobility. It shows the relationship between a cohort’s birth year, on the horizontal axis, and the share of the cohort whose income exceeded that of their parents at age 30.)

The study from Chetty and his co-authors also documented that the reported decline in social mobility was widespread. It had declined in all 50 states over the 44 years covered by the study. In addition, their finding of declining social mobility still held after accounting for the effect of taxes and government transfers (including cash payments and payments in kind) on household income. All in all, their study showed that, “Severe Inequality Is Incompatible With the American Dream,” to quote the title of an Atlantic magazine article published at the time. Since then, the Chetty group and others have continued their investigations of inequality and social mobility, which are available on the Opportunity Insights website (opportunityinsights.org).

The stunning results of the Chetty group’s study got the attention of the Wall Street Journal. The headline of Bob Davis’s December 2016 Journal article summed up their findings succinctly: “Barely Half of 30-Year-Olds Earn More Than Their Parents: As wages stagnate in the middle class, it becomes hard to reverse this trend.”

Davis was correct to point to the study’s emphasis on the difficulty of reversing the trend of declining mobility. The Chetty group was convinced “that increasing GDP [gross domestic product] growth rates alone” would not restore social mobility. They argued that restoring the more equal distribution of income experienced by the 1940s cohort would be far more effective. In their estimation, it would “reverse more than 70% of the decline in mobility.”

Social Mobility Has Gotten Worse, Not Better

Since 2014, neither U.S. economic growth nor relative equality has recovered, let alone returned to the levels that undergirded the far greater social mobility of the 1940s cohort. Today, the economic position of young adults is no longer improving relative to that of their parents or their grandparents.

President Donald Trump was fond of claiming that he oversaw the “greatest economy in the history of our country,” during his first term (2017–2020). But even before the onset of the Covid-19-induced recession, his economy was neither the best nor good, especially when compared to the economic growth rates enjoyed by the 1940s cohorts who reached age 30 during the 1970s. During the 1950s and then again during the 1960s, U.S. economic growth averaged more than 4% a year corrected for inflation, and it was still growing at more than 3% a year during the 1970s. From 2015 to 2019, the U.S. economy grew a lackluster 2.6% a year and then just 2.4% a year during the 2020s (2020–2024).

Also, present-day inequality continues to be far worse than in earlier decades. In his book-length telling of the story of the American Dream, Ours Was the Shining Future, journalist David Leonhardt makes that clear. From 1980 to 2019, the household income of the richest 1% and the income of the richest 0.001% grew far faster than they had from 1946 to 1980, while the income of poorer households, from the 90th percentile on down, grew more slowly than they had during the 1946 to 1980 period. As a result, from 1980 to 2019, the income share of the richest 1% nearly doubled from 10.4% to 19%, while the income share of the bottom 50% fell from 25.6% to 19.2%, hardly more than what went to the top 1%. Beyond that, in 2019, the net worth (wealth minus debts) of median, or middle-income, households was less than it had been in 2001, which, as Leonhardt points out, was “the longest period of wealth stagnation since the Great Depression.”

No wonder the American Dream took such a beating in the July 2025 Wall Street Journal-NORC at the University of Chicago poll. Just 25% of people surveyed believed they “had a good chance of improving their standard of living,” the lowest figure since the survey began in 1987. And according to 70% of respondents, the American Dream no longer holds true or never did. That figure is the highest in 15 years.

In full carnival barker mode, Trump is once again claiming “we have the hottest economy on Earth.” But the respondents to the Wall Street Journal-NORC poll aren’t buying it. Just 17% agreed that the U.S. economy “stands above all other economies.” And more than twice that many, 39%, responded that “there are other economies better than the United States.” It’s a hard sell when the inflation-adjusted weekly wages of nonsupervisory workers are still lower than what they had been in 1973, now more than half a century ago.

And economic worries are pervasive. Three-fifths (59%) of respondents were concerned about their student loan debt, more than two-thirds (69%) were concerned about housing, and three-quarters (76%) were concerned about health care and prescription drug costs.

Rising housing costs have hit young adults especially hard. The median price of a home in 1990 was three times the median household income. In 2023, that figure had reached nearly five times the median household income. And the average age of a first-time homebuyer had increased from 29 in 1980 to 38 in 2024.

Finally, in their 2023 study, sociologists Rob J. Gruijters, Zachary Van Winkle, and Anette E. Fasang found that at age 35, less than half (48.8%) of millennials (born between 1980 and 1984) owned a home, well below the 61.6% of late baby boomers (born between 1957 and 1964) who had owned a home at the same age.

Dreaming Big

In their 2016 study, the Chetty group writes that, “These results imply that reviving the ‘American Dream’ of high rates of absolute mobility would require economic growth that is spread more broadly across the income distribution.”

That’s a tall order. Fundamental changes are needed to confront today’s economic inequality and economic woes. A progressive income tax with a top tax rate that rivals the 90% rate in the 1950s and early 1960s would be welcomed. But unlike the top tax rate of that period, the income tax should tax all capital gains (gains in wealth from the increased value of financial assets such as stocks) and tax them as they are accumulated and not wait until they are realized (sold for a profit). Also, a robust, fully refundable child tax credit is needed to combat childhood poverty, as are publicly supported childcare, access to better schooling, and enhanced access to higher education. Just as important is enacting universal single-payer health care and increased support for first-time homebuyers.

The belief that “their kids could do better than they were able to,” was what Chetty told the Wall Street Journal motivated his parents to emigrate from India to the United States. These fundamental changes could make the American Dream the reality that it never was.

© 2023 Dollars & Sense

John Miller

John Miller is a member of the Dollars & Sense collective, is professor of economics at Wheaton College.

Full Bio >

Whatever Happened to Trump’s “Golden Age” for American Workers?

MORE LIKE A GOLDEN SHOWER

by Lawrence S. Wittner / December 26th, 2025

Although Donald Trump’s Department of Labor announced in April 2025 that “Trump’s Golden Age puts American workers first,” that contention is contradicted by the facts.

Indeed, Trump has taken the lead in reducing workers’ incomes. One of his key actions along these lines occurred on March 14, 2025, when he issued an executive order that scrapped a Biden-era regulation raising the minimum wage for employees of private companies with federal contracts. Some 327,300 workers had benefited from Biden’s measure, which produced an average wage increase of $5,228 per year. With Trump’s reversal of policy, they became ripe for pay cuts of up to 25 percent.

America’s farmworkers, too, many of them desperately poor, are now experiencing pay cuts caused by the Trump administration’s H-2A visa program, which is bringing hundreds of thousands of foreign agricultural workers to the United States under new, lower-wage federal guidelines. The United Farm Workers estimates that this will cost U.S. farm workers $2.64 billion in wages per year.

As in the past, Trump and his Republican Party have blocked any increase in the federal minimum wage―a paltry $7.25 per hour―despite the fact that it has not been raised since 2009 and, thanks to inflation, has lost 30 percent of its purchasing power. By 2025, this wage had fallen below the official U.S. government poverty level.

Furthermore, the Trump administration is promoting subminimum wages for millions of American workers. Although the Biden administration had abolished the previous subminimum wage floor for workers with disabilities by raising it to the federal minimum wage, the Trump Labor Department has restored the subminimum wage. In addition, the Trump administration is proposing to strip 3.7 million home-care workers of their current federal minimum wage guarantee.

Trump’s Labor Department has also scrapped the Biden plan to expand overtime pay rights to 4.3 million workers who had previously lost eligibility for it, thanks to inflation. And it is promoting plans to classify many workers as independent contractors, thereby depriving them of key labor rights, including minimum wage and overtime pay.

Not surprisingly, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on December 18, 2025, that, from November 2024 to November 2025, the annual growth of the real wages (wages adjusted for inflation) of American workers had fallen to 0.8 percent.

Trump’s policies have also fostered unemployment.

Probably the best-known example of this is the Trump administration’s chaotic purge, led by billionaire Elon Musk, of 317,000 federal workers without any clear rationale or due process. On top of this, however, it has shut down massive construction projects, especially in the renewable energy industry. Trump’s recent order to halt the construction of the huge wind farms off the East Coast is expected to result in the firing of thousands of workers.

Ironically, as two economic analysts reported in mid-December 2025, “key sectors of the economy that are central to Trump’s agenda have contracted, with payrolls in manufacturing, mining, logging and professional business services all falling over the last year.” Despite Trump’s repeated claims to be reviving U.S. manufacturing through tariffs, 58,000 U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost between April (when the administration announced its “Liberation Day” tariffs) and September 2025.

Consequently, U.S. unemployment, which, during the Biden presidency, had bottomed out at 3.4 percent, had by November 2025 (the last month for which government statistics are available) risen to 4.6 percent. This is the highest unemployment level in four years, leaving 7.8 million workers unemployed―700,000 more than a year before.

The Trump administration has also seriously undermined worker safety and health. According to the latest AFL-CIO study, workplace hazards kill approximately 140,000 workers each year, with millions more injured or sickened. Although the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is supposed to enforce health and safety standards, the Trump administration cut its workplace inspections by 30 percent, thereby reducing inspections of each site to one every 266 years.

Similarly, Trump has nearly destroyed the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, which provides research on workplace safety standards, by reducing its staffing from 1,400 employees to 150 and slashing its budget by 80 percent.

Through executive action, the Trump administration eliminated specific measures taken to protect workers. This process included blocking a Biden rule to control heat conditions in workplaces, where 600 workers die from heat-related causes and nearly 25,000 others are injured every year. Moreover, in the spring of 2025, the Trump administration announced that it would not enforce a Biden rule to protect miners from dangerous silica exposure and moved to close 34 Mine Safety and Health Administration district offices. Although a public uproar led to a reversal of the office closures, the administration then proposed weakening those offices’ ability to impose mine safety requirements and also weakening workplace safety penalties for businesses.

In addition, Trump appointed corporate executives to head relevant federal agencies, gutted Equal Employment Opportunity guidelines, and, in March 2025, issued an executive order that terminated collective bargaining rights for more than a million federal government workers. This last measure, the largest single union-busting action in American history, ended union representation and protections for one out of every 14 unionized workers in the United States.

In a special AFL-CIO report, issued on December 22, 2025, the labor federation’s president, Liz Shuler, and secretary-treasurer, Fred Redmond, declared: “Since Inauguration Day . . . the fever dreams of America’s corporate billionaires have come to life with a relentless assault on working people,” and “every day has brought a new challenge and attack: On federal workers. On our unions and collective bargaining rights. On the agencies that stand up for us and the essential services we rely on. . . . On our democracy itself.”

Although Trump’s second term in office might have provided a “Golden Age” for the President and his fellow billionaires, it has produced harsh and challenging times for American workers.