The US War on Venezuela Began in 2001

The United States had no problem with Venezuela per se, not with the country nor with its former oligarchy. The problem that the United States government and its corporate class have is with the process set in motion by the first government of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

In 2001, Chávez’s Bolivarian process passed a law called the Organic Hydrocarbons Law, which asserted state ownership over all oil and gas reserves, held upstream activities of exploration and extraction for the state-controlled companies, but allowed private firms – including foreign firms – to participate in downstream activities (such as refining and sale). Venezuela, which has the world’s largest petroleum reserves, had already nationalized its oil through laws in 1943 and then repeated in 1975. However, in the 1990s as part of the neoliberal reforms pushed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and by the large US-owned oil companies, the oil industry was substantially privatized.

When Chávez enacted the new law, it brought the state back into control of the oil industry (whose foreign oil sales were responsible for 80% of the country’s external revenues). This deeply angered the US-owned oil companies – particularly ExxonMobil and Chevron – which put pressure on the government of US President George W. Bush to act against Chávez. The US tried to engineer a coup to unseat Chávez in 2002, which lasted for a few days, and then pushed the corrupt Venezuelan oil company management to initiate a strike to damage the Venezuelan economy (it was eventually the workers who defended the company and took it back from the management). Chávez withstood both the coup attempt and the strike because he had the vast support of the population. Maria Corina Machado, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2025, started a group called Sumaté (“Join Up”), which placed a recall referendum on the ballot. About 70% of the registered voters came to the polls in 2004, and a large majority (59%) voted to retain Chávez as the president.

But neither Machado nor her US backers (including the oil companies) rested easy. From 2001 till today, they have tried to overthrow the Bolivarian process – to effectively return the US-owned oil companies to power. The question of Venezuela, then, is not so much about “democracy” (an overused word, which is being stripped of meaning) but about the international class struggle between the right of the Venezuelan people to freely control their oil and gas and that of the US-owned oil companies to dominate Venezuelan natural resources.

The Bolivarian process

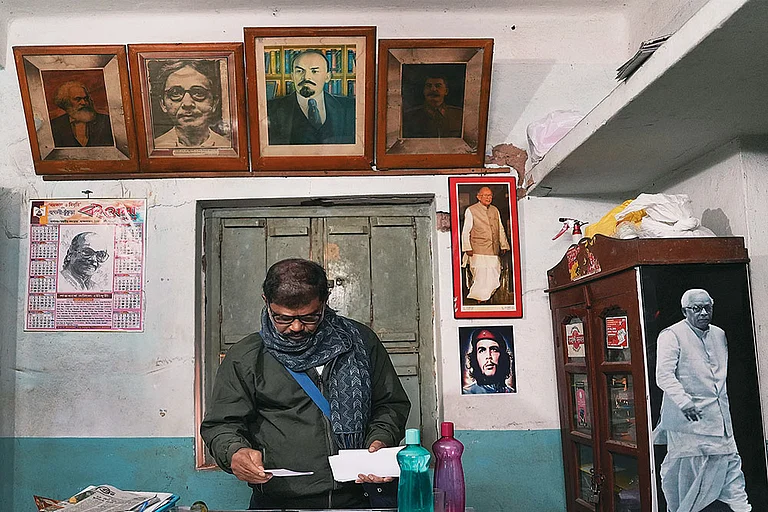

When Hugo Chávez appeared on the political scene in the 1990s, he captured the imagination of most of the Venezuelan people – particularly the working-class and the peasantry. The decade was marked by the dramatic betrayals by presidents who promised to secure the oil-rich country from IMF-imposed austerity and then adopted those same IMF proposals. It did not matter if they were social democrats (such as Carlos Andrés Pérez of Democratic Action, president from 1989 to 1993) or conservatives (such as Rafael Caldera of the Christian Democrats, president from 1994 to 1999). Hypocrisy and betrayal defined the political world, while high levels of inequality (with the Gini index at a staggering 48.0) gripped the society. The mandate for Chávez (who won the election with 56% against 39% for the candidate of the old parties) was against this hypocrisy and betrayal.

It helped Chávez and the Bolivarian process that oil prices stayed high from 1999 (when he took office) till 2013 (when he died at 58, very young). Having taken hold of the oil revenues, Chávez turned them over to make phenomenal social gains. First, he developed a set of mass social programs (misiones) that redirected oil revenues to meet basic human needs such as primary healthcare (Misión Barrio Adentro), literacy and secondary education for the working-class and peasantry (Misión Robinson, Misión Ribas, and Misión Sucre), food sovereignty (Misión Mercal and then PDVAL), and housing (Gran Misión Vivienda).

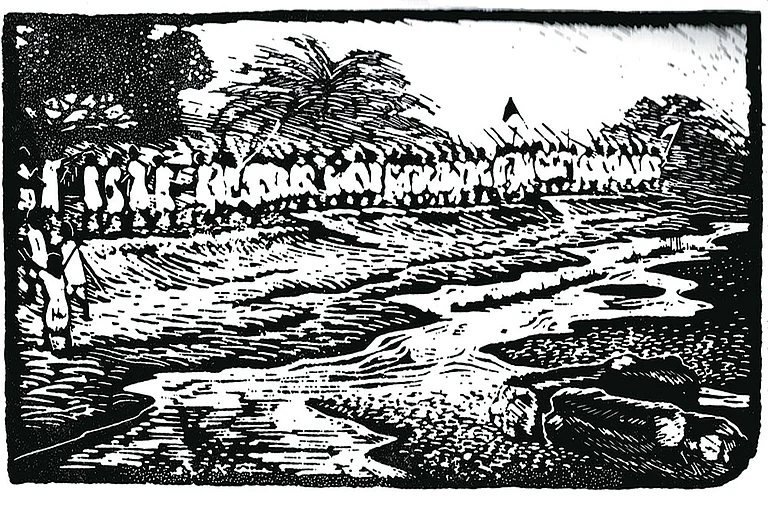

The state was reshaped as a vehicle for social justice and not an instrument to exclude the working-class and peasantry from the gains of the market. As these reforms advanced, the government moved to build popular power through participatory instruments such as the communes (comunas). These communes emerged first out of popular consultancy assemblies (consejos comunales) and then developed into popular bodies to control public funds, plan for local development, generate communal banks, and form local, cooperative enterprises (empresas de producción social). The communes represent one of the Bolivarian process’ most ambitious contributions: an effort – uneven but historically significant – to construct popular power as a durable alternative to oligarchic rule.

The US-imposed hybrid war on Venezuela

Two events took place in 2013-14 that deeply threatened the Bolivarian process: first, the untimely death of Hugo Chávez, without doubt the driving force of revolutionary energy in the country, and second, the slow and then steady collapse of oil revenues. Chávez was followed as president by the former foreign minister and trade unionist Nicolás Maduro, who tried to steady the ship but faced a severe challenge when oil prices, which peaked in June 2014 at roughly USD 108 per barrel, fell dramatically in 2015 (below USD 50) and then by January 2016 (below USD 30). For Venezuela, which relied upon foreign crude oil sales, this decline was catastrophic. The Bolivarian process could not revise the oil-dependent redistribution (not just within the country but in the region, including through PetroCaribe); it remained trapped by dependence on oil exports and therefore by the contradictions of being a rentier state. Equally, the Bolivarian process had not expropriated the wealth of the dominant classes, which continued to lean heavily on the economy and society, and therefore prevented a full-scale transition to a socialist project.

Before 2013, the United States, its European allies, and oligarchic forces in Latin America had already forged their weapons for a hybrid war against Venezuela. After Chávez won his first election in December 1998 and before he took office the next year, Venezuela saw accelerated capital flight as the Venezuelan oligarchy took their wealth to Miami. During the coup attempt and the oil lockout, there was more evidence of capital flight, which weakened the monetary stability of Venezuela. The United States government began to lay the diplomatic groupwork to isolate Venezuela, characterizing the government as a problem and building an international coalition against it. This led, by 2006, to restrictions on Venezuela for access to international credit markets. Credit rating agencies, investment banks, and multilateral institutions steadily raised borrowing costs, making refinancing more difficult well before the US placed formal sanctions on Venezuela.

After the death of Chávez, and with oil prices lowered, the United States began a focused hybrid war against Venezuela. Hybrid war refers to the coordinated use of economic coercion, financial strangulation, information warfare, legal manipulation, diplomatic isolation, and selective violence, deployed to destabilize and reverse sovereign political projects without the need for full-scale invasion. Its objective is not territorial conquest but political submission: the disciplining of states that attempt redistribution, nationalization, or independent foreign policy.

Hybrid war operates through the weaponization of everyday life. Currency attacks, sanctions, shortages, media narratives, NGO pressure, judicial harassment (lawfare), and engineered legitimacy crises are designed to erode state capacity, exhaust popular support, and fracture social cohesion. The resulting suffering is then presented as evidence of internal failure, masking the external architecture of coercion. This is precisely what Venezuela has faced since the US illegally placed financial sanctions on the country in August 2017, these were then deepened with secondary sanctions in 2018. Because of these sanctions, Venezuela has faced the disruption of all payment systems and trade channels and forced overcompliance with US regulations. Meanwhile, media narratives in the West systematically downplayed sanctions, while amplifying inflation, shortages, and migration as purely internal phenomenon, reinforcing regime-change discourse. The collapse of living standards in Venezuela between 2014 and 2017 cannot be divorced from this layered strategy of economic asphyxiation.

Mercenary attacks, sabotage of the electrical grid, creation of a conflict generated to benefit ExxonMobil between Guyana and Venezuela, invention of an alternative president (Juan Guaidó), provision of the Nobel Peace Prize to someone calling for a war against her own country (Machado), attempted assassination of the president, bombings of fishing boats off the Venezuelan coast, seizure of oil tankers leaving Venezuela, buildup of an armada off the coast of the country: each of these elements is designed to create neurological tension within Venezuela leading to the surrender of the Bolivarian process in favor of a return to 1998 and then an annulment of any hydrocarbon law that promises the country sovereignty.

If the country were to return to 1998, as Maria Corina Machado promises, all the democratic gains made by the misiones and the comunas as well as by the Constitution of 1999 will be invalidated. Indeed, Machado said that a US bombing of her fellow Venezuelans would be “an act of love”. The slogan of those who want to overthrow the government is Ahead to the Past.

In October 2025, meanwhile, Maduro told an audience in Caracas in English, “listen to me, no war, yes peace, the people of the United States”. That night, in a radio address, he warned, “No to regime change, which reminds us so much of the endless, failed wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and so on. No to CIA-orchestrated coups d’état.” The line, “no war, yes peace”, was taken up on social media and remixed into songs. Maduro appeared several times at rallies and meetings with music ablaze, singing, no war, yes peace, and – on at least one occasion – wearing a hat with that message.

Courtesy: Peoples Dispatch

Why Trump’s Curbs on Venezuela Oil Tankers Tests Limits of International Law

On December 16, the United States (US) announced measures to block oil tankers entering and leaving Venezuela. The Trump administration alleges that Nicolás Maduro’s regime is engaged in drug trafficking and human trafficking. The U.S has expanded its naval presence in the region, ostensibly to interrupt the drug-smuggling boat.

According to TankerTrackers.com, more than 30 out of 80 vessels in Venezuelan waters or approaching Venezuela are under US sanctions. Over time, Trump's position has shifted from allegations of drug trafficking to claims that the Maduro government is using stolen oil to finance, what he terms, “drug terrorism” and human trafficking. In response, Venezuela has accused Washington of illegally expropriating its resources.

Considering Venezuela’s over-dependence on oil, the move carries far-reaching geopolitical implications. China has expressed its displeasure over the “unilateral bullying,” and Mexico has urged the United Nations to intervene to diffuse the tensions. Meanwhile, Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller claimed in a post on Xt that the “tyrannical expropriation” by Venezuela amounted to “the largest recorded theft of American wealth and property.” Joaquin Castro, a Democrat from Texas, has termed these measures “an act of war.” Maduro has characterized the move as an attempt at regime change and an assertion of US control over Venezuelan territory and resources.

The total blockade by the US has left the scholars divided. According to NYU professor Ryan Goodman, “[t]here is no legal justification for a military blockade based on the grievances President Trump listed.” Writing for Just Security, Michael Schmitt and Rob McLaughlin argue that the US actions amount to a threat or use of armed force against oil tankers entering or leaving the territorial waters of Venezuela. They characterise blockade as the use of force, even prior to the actual use of force under Article 42 of the UN Charter, which expressly lists blockade as a coercive measure when non-forcible means have failed. They further argue that a blockade constitutes aggression within the meaning of United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 3314.

This post contends that the act of blockade constitutes a violation of jus cogens or peremptory norm of international law, foreclosing any defence that the US might otherwise invoke. Such a violation would attract a higher degree of international responsibility under the law of State responsibility. The analysis is confined to jus ad bellum and does not probe into jus in bello.

Can blockade be an act of ‘aggression’?

The UN Charter does not authorise the unlawful use of force amounting to aggression. Rather, it vests the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) with authority to act against acts of aggression. Unlike other forms of use of force, aggression involves a particularly grave use of force. This distinction is found in the introductory paragraph of UNGA Resolution 3314, which characterizes aggression as the “most serious and dangerous form of the illegal use of force.”

Although the UNSC is competent to determine acts amounting to aggression beyond the non-exhaustive list provided in Article 3 of Resolution 3314, according to Mary Ellen O'Connell, this determination is often shaped by political considerations. Moreover, such determinations are vulnerable to a permanent member blocking a resolution on aggression. Article 3(c) expressly recognizes the blockade of a State's ports or coasts by the armed forces of another State as an act of aggression. Hence, the US blockade of ships entering and exiting Venezuela, while falling within this definition, is unlikely to attract formal UNSC censure given the possibility of a US veto.

Although the UNSC is competent to determine acts amounting to aggression beyond the non-exhaustive list provided in Article 3 of Resolution 3314, according to Mary Ellen O'Connell, this determination is often shaped by political considerations. Moreover, such determinations are vulnerable to a permanent member blocking a resolution on aggression.

A ‘peacetime blockade’ would qualify as a use of force even before any kinetic engagement with the ships, since Article 42 of the UN Charter provides for blockade as a measure which the UNSC can authorise when non-forceable actions fail. By implication, the unilateral imposition of a blockade, without the UNSC’s authorisation, breaches the prohibition on the use of force.

US officials have justified these actions on grounds of self-defence, a claim decipherable from Trump’s Truth Social post in the face of the drug threat. However, the shift in Trump’s position from interdicting drug-boats to claims over oil and other assets significantly weakens any claim of self-defence. Additionally, for invoking self-defence, the threshold of ‘armed attack’ is high; for instance, in the Nicaragua case, the ICJ categorised an armed attack as “the most grave” form of the use of force. On this reasoning, the US blockade would itself constitute a grave use of force, and potentially trigger Venezuela's right to self-defence. Finally, blockade cannot be justified on political, economic, military, or any other grounds, as affirmed by UNGA Resolution 3314.

Aggression as a violation of jus cogens

Jus cogens are peremptory norms of international law from which no derogation is permitted. In the hierarchy of norms, these are placed higher than treaties and customary international law. Scholars like Katie A. Johston and Corten identify prohibition of aggression as a jus cogens norm. Aggression is commonly used alongside the unlawful use of force, but its classification depends on the gravity and character of the force employed. In this context, in the Oil Platforms case, the ICJ did not exclude the possibility that the mining of a military vessel might be sufficient to bring into play the “inherent right of self-defence.”

Similarly, the blockade of the port of Mariupol and the Sea of Azov was regarded as constituting aggression; accordingly, scholars like James A. Green et al. regard the invasion of Ukraine as an act of aggression and a violation of jus cogens. Several authoritative international instruments identify aggression as a jus cogens norm. For instance, the International Law Commission’s (ILC) Draft Conclusion on Identification and Legal Consequences of Peremptory Norms of General International Law (jus cogens) in its non-exhaustive list locates prohibition on aggression as jus cogens; likewise, the ILC report on fragmentation identifies prohibition on aggression as the most frequently cited candidate for jus cogens status.

First, the supreme status of the prohibition of aggression as a jus cogens norm would entail an obligation erga omnes, wherein States not directly affected by the acts of the US could bring claims against it. This could be achieved through third-party countermeasures (sanctions) or by taking the US to the International Court of Justice. Furthermore, domestic jurisdictional claims would be strengthened if the prohibition on aggression were categorised as jus cogens, as States like Germany, Ukraine, and Switzerland have criminalised aggression in their domestic laws.

Second, States cannot be precluded from responsibility for jus cogens breaches. As Article 26 of the ILC Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA) states: “Nothing in this chapter precludes the wrongfulness of any act of a State which is not in conformity with an obligation arising under a peremptory norm of general international law.” As Norman Finkelstein notes, “we’re upping the ante in order to try to get them to engage in an act of aggression that would then justify an act of self-defence on our part.” Further, the Pentagon officials view the blockade as a “quarantine,” a language employed during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis to cordon off weapon shipments from the Soviet Union. Such framing does not, however, alter the legal character of the act under international law. Hence, any justification, like self-defence, cannot be used to justify a blockade.

The ICJ’s position on self-defence for acts of aggression is evident in the Nicaragua case. There, the US attempted to justify collective self-defence for Nicaragua’s alleged aggression against El Salvador, Honduras, and Costa Rica; the argument was dismissed, as El Salvador’s request was not supported by an armed attack capable of triggering self-defence.

Jus cogens are peremptory norms of international law from which no derogation is permitted. In the hierarchy of norms, these are placed higher than treaties and customary international law.

Third, the jus cogens nature of the act means an additional layer of responsibility, beyond reparations. Third States have obligations to cooperate to end the serious breaches within the confines of the UN Charter; therefore, as confirmed in Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius, “all member States to co-operate with the United Nations to end the breach in question.” Accordingly, the UNGA could pass resolutions condemning US actions and recommend the UNSC to take coercive actions.

If this fails, as I have argued, suspension of the US could be contemplated from the United Nations. Moreover, third States are under an obligation not to assist in the commission of an unlawful act. Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez has claimed that Trinidad and Tobago actively participated in the seizure of the US oil tankers off the country’s coast. If substantiated, facilitation of logistical access, such as permitting the use of airspace or airports, could amount to assistance in an unlawful act. Thus, third States, like Trinidad and Tobago, could be equally complicit in violating jus cogens.

The Trump administration has been repeatedly accused of breaching international law norms through unilateral economic sanctions, use of force in the Middle East, violations of non-refoulement, arbitrary detention, etc. Seen in this light, the recent actions are an extension of established US foreign policy practice. This is perhaps reflected in the US National Security Strategy which states: “The purpose of foreign policy is the protection of core national interests.” Nevertheless, the present blockade tests the outer limits of the international legal order and the continuing viability of the prohibition on the use of force.

The views are personal.

Courtesy: The Leaflet