Indian Tanker Seizures Threaten Market Shift and Rift With Iran

The Indian seizure of three dark fleet tankers associated with Iranian oil exports has been well-known within the industry for days, even though the Indian Coast Guard quickly withdrew a post describing their seizure. But now Reuters has confirmed that the seizures did indeed take place, and that the tankers are being held off the western Indian coast by the Indian Coast Guard.

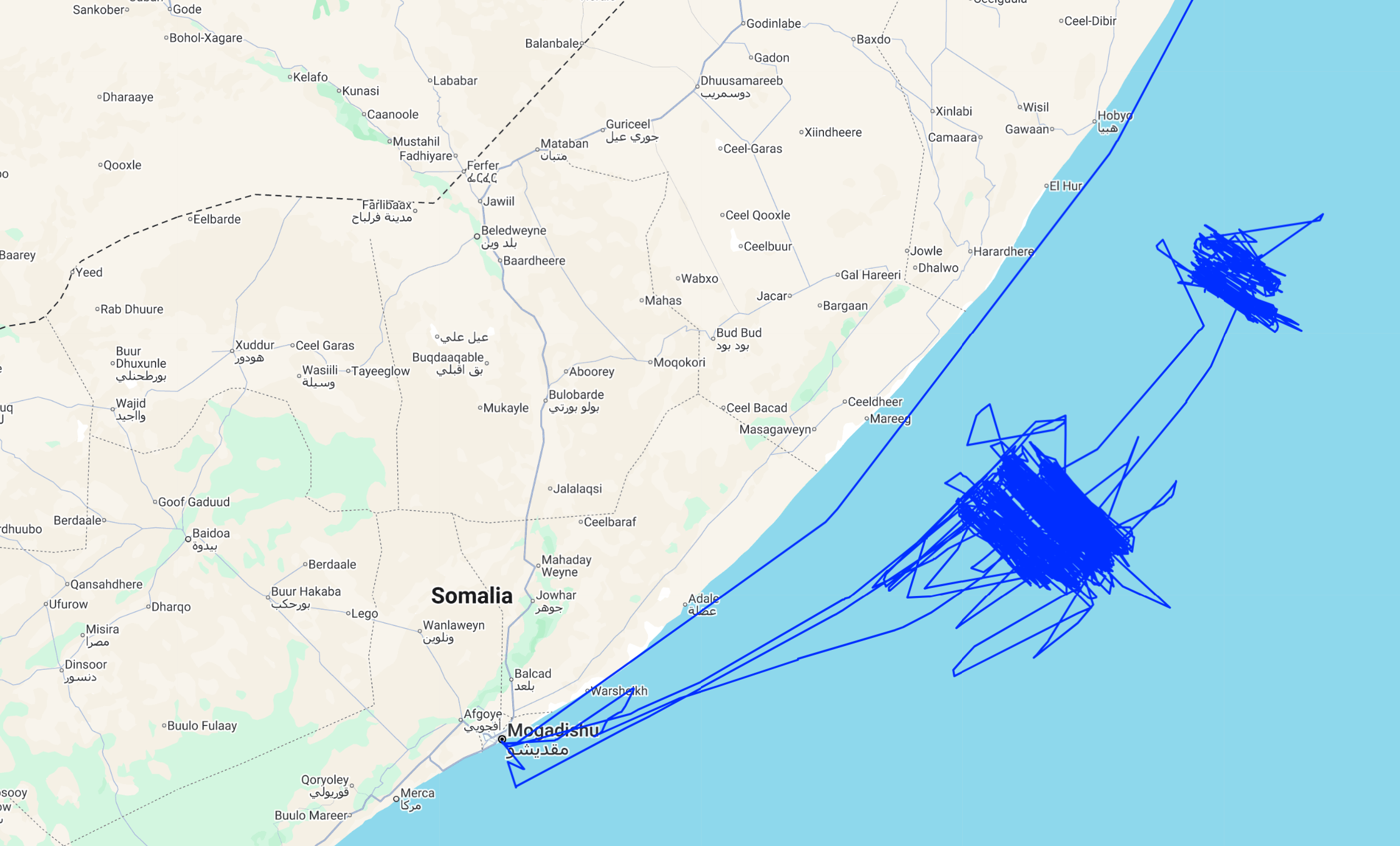

On February 5, the ICG boarded three Iran-associated sanctions-busting tankers about 100 nautical miles to the west of Mumbai. The tankers were then escorted to anchorages off Mumbai, their current locations being confirmed by multiple AIS aggregating sites. The tankers concerned are the Al Jafzia (IMO 9171498), Asphalt Star (IMO 9463528) and the Iranian-flagged Stellar Ruby (IMO 9555199), all of which are US-sanctioned following multiple journeys in which Iranian oil has been loaded, transshipped and delivered.

Iran has issued a statement denying any connection to the tankers or their cargoes.

At the time of the seizure, the Maritime Executive noted that this Indian action may have been connected with the advertised participation of Iran’s 103rd Naval Flotilla in the International Fleet review, which India is about to host in Visakhapatnam, the headquarters of the Indian navy’s Eastern Command. It was suggested that the Indian move was a subtle way of suggesting to the Iranians that their invitation had been rescinded, and that they were no longer welcome, particularly as the Indian government intend to use the occasion of the fleet reviw to advertise the impending purchase of more Boeing Poseidon P-8I aircraft, a deal which could have been jeopardized by any Iranian presence. Now however, as the Indian Navy announces the arrival of foreign ships for the fleet review, Iranian participation is no longer being trumpeted.

Iran is still expected to participate - however, not with the announced three ships of the 103rd Flotilla, but likely with a single Moudge-class frigate IRINS Dena (F75) instead.

Of more significance than the Iranian participation in the International Fleet Review, the Indian Coast Guard’s seizures will be of much greater potential impact on international oil flows. India has been importing large volumes of sanctioned oil for domestic use, both from Iran and Russia. But it has also been refining significant volumes of crude from these sources, and then re-exporting it to countries such as Australia, labeled as Indian rather than sanctioned oil. If the Indian Coast Guard seizures are maintained, then Indian refiners will need to switch the source of their feedstock – and what they will be able to purchase instead will not enjoy the discounts which could be asked for sanctioned oil.

Top image courtesy VesselFinder

Iran's IRGC Prompts False Alarm in Strait of Hormuz

The IRGC Navy has made a number of half-hearted attempts to disrupt traffic in the Straits of Hormuz in recent weeks.

On January 29, the IRGC Navy warned that areas of the Straits of Hormuz would be closed for a live fire exercise. On the next day, CENTCOM warned ‘the IRGC to conduct the announced naval exercise in a manner that is safe, professional and avoids unnecessary risk to freedom of navigation for international maritime traffic’, and the Iranians then canceled the planned exercise.

Several days later on February 3, the United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) in Dubai advised that an unidentified ship was hailed on VHF by numerous small armed vessels early and had been requested to stop. This was a poor choice of target for the IRGC to make, as the ship in question was the US-flagged Crowley-managed Stena Imperative (IMO 9666077), chartered under the Department of Defense Tanker Security Program. The master of the ship ignored the request and the nearby USS McFaul (DDG-74) promptly saw off the threat.

The IRGC made a third disruptive attempt when warning that they would carry out a ‘smart exercise’ and live firing off Sirik on the eastern side of the Straits of Hormuz between 03.30 and 18.30 UTC on February 17. Some commentators suggested that this would entail closure of the northern and inbound leg of the Straits of Hormuz Traffic Separation Scheme. However, this lane lies within Omani territorial waters, and Oman would not countenance such a closure.

Oman enforces a strict policy on maintaining unimpeded use of the Traffic Separation Scheme. Ships approaching the Straits are normally hailed separately and successively by the Iranian Navy (Nedaja), the IRGC Navy and the Iranian Coastguard. When vessels are in Iranian waters it is maritime custom and practice for vessels to reply. But if such Iranian calls are made when vessels are in Omani waters, vessels are not obliged to respond, and the Omani authorities will normally jam such calls when their radar systems indicate that the vessel being hailed is in Omani waters.

The Iranian warning of its impending exercise was accompanied by a video showing various IRGC speed boats, but this was historic footage of a previous exercise, and no ships or boats were identified as about to take part in the exercise. The allusion to a ‘smart’ exercise may imply that no actual vessels are involved. An unidentified IRGC Navy Shahid Soleimani Class missile corvette (but likely to be IRIS Shahid Soleimani (FS313-01)) was seen heading East off Kish Island on February 16, but such activity is not indicative of participation in the forthcoming exercise.

All these IRGC-initiated half-hearted events, or non-events, are indicative of Iran’s current state of nervousness and sense of vulnerability. It is significant that the regular Iranian navy (Nedsa) is not playing a part in these charades, and indeed is keeping itself invisible and well out of the way, for the most part by holding off in the northern Indian Ocean.

Strait of Hormuz Traffic Separation Scheme shipping channels (Goran Tek-en / CC BY), with the exercise area off Sirik indicated (CJRC).

By Scott N. Romaniuk, Erzsébet N. Rózsa and László Csicsmann

Iran is confronting an unprecedented water crisis. Rivers that have sustained settlements and agriculture for centuries are drying, while groundwater reserves are being extracted far beyond natural replenishment—over 70% of major aquifers are considered overdrawn. According to Isa Bozorgzadeh, spokesperson for Iran’s water industry, many plains and reservoirs have reached critically low levels. Over the past two decades, the country’s renewable water resources have declined by more than a third, pushing Iran to the brink of absolute water scarcity.

Drought cycles are becoming more frequent and severe; this past autumn marked one of the driest periods in the last 20 years in contemporary Iranian history. For decades, national development policies assumed that engineering and extraction could overcome environmental limits. Today, those limits are reasserting themselves, and shortages are moving from rural peripheries into major cities, placing pressure on a political system already managing numerous economic, social, and national security challenges. Rising scarcity underscores the multifaceted ways in which water intersects with livelihoods, public trust, and national security, creating pressures that extend from rural communities to urban centers and shaping Iran’s domestic and regional policies.

These long-term pressures are not solely the product of climate variability. They reflect cumulative policy decisions, infrastructure choices, and social priorities that have consistently prioritized water-intensive agriculture, urban expansion, and industrial development. Iran’s national security is no longer defined solely by armies, weapons, or borders—it now hinges on something far more fundamental: water. Understanding these drivers is crucial to grasping how the country arrived at its current crisis, where domestic vulnerabilities intertwine with mounting regional tensions over shared water resources.

How Iran Got Here

While droughts have made Iran’s situation worse, various studies and official reports show that the main causes are mostly related to policies and infrastructure. The Islamic Republic’s long-standing commitment to agricultural self-sufficiency—complemented by necessity due to international sanctions—prioritized national food security over environmental sustainability. Crops such as rice, wheat, and sugar beet were promoted—even in areas unsuitable for high water consumption. Subsidized water pricing and low-cost energy encouraged excessive irrigation, depleting rivers and aquifers.

Urban and industrial expansion, with Iranian urbanization standing at approximately 77 percent, has further compounded pressures on water resources. The licensing of hundreds of thousands of wells, many lacking proper oversight, has accelerated groundwater extraction far beyond natural replenishment rates. In Tehran, ageing century-old water infrastructure, including the ancient underground qanat/kariz system, contributes to significant leakage, intensifying shortages even in years of normal rainfall.

In addition, Minister Ali Abadi has noted extraordinary factors—such as disruptions from regional conflicts, including the recent 12-day war with Israel—that have further exacerbated the capital’s water stress, prompting the introduction of a recently launched plan to move the capital closer to the more water-abundant Makran region along the Gulf of Oman. In some areas, aquifers have fallen so drastically that land subsidence has become irreversible, damaging roads, buildings, and farmland. Policies intended to secure economic and national resilience instead produced resource overreach, leaving Iran highly vulnerable to both climatic variability and systemic infrastructure failures.

Water Scarcity as a Driver of Unrest and Inequality

Water scarcity increasingly threatens Iran’s social cohesion and national stability. Rural communities dependent on irrigation have witnessed orchards wither and livestock decline, prompting waves of migration to already stressed urban areas. These environmental pressures erode traditional livelihoods and ignite political grievances, as seen in demonstrations in Isfahan, Khuzestan, and other provinces under the slogan ‘We are thirsty!’ (Ma teshne im!). Residents frequently accuse authorities of misallocating water to industrial users or favored regions, while government responses often prioritize containment over addressing the root causes.

Scarcity also exacerbates long-standing regional and ethnic disparities. Inter-provincial water transfers—from Khuzestan and Chaharmahal-va-Bakhtiari to central provinces such as Isfahan and Yazd—have deepened resentment in peripheral areas. Arab communities in Khuzestan, Bakhtiari, and Lor populations in the southwest view these projects as benefiting Persian-majority industrial centers, reinforcing perceptions of historical neglect and political marginalization. Various protests in these regions, notably the farmers’ protest in Isfahan in April 2025, have occasionally escalated into clashes with security forces, road blockages, and attacks on construction sites, highlighting how hydrological stress intersects with ethnic identity, structural inequalities, and contested state–society relations.

As environmental decline accelerates, water scarcity risks transforming from an episodic trigger of unrest into a sustained driver of domestic tension and center–periphery conflict, challenging both local livelihoods and national cohesion.

Urban and Rural Vulnerability

Once considered insulated from water stress, urban areas are increasingly facing challenges to this assumption. Major cities depend on interconnected reservoirs and pipelines vulnerable to both climatic fluctuations and disruptions over long distances. Tehran, home to some 9-10 million residents (but some 15 million if the metropolitan area is considered), relies heavily on mountain reservoirs threatened by declining snowpack and rising temperatures.

Similarly, Mashhad and Shiraz have faced rotational cutoffs that strain the public’s patience, while provincial centers in arid regions occasionally experience complete supply interruptions. Significantly, the Zayandeh-Rood—meaning “life-giving river”—which gave rise to Isfahan, the Safavid capital of the 16th century, and long stood as one of Iran’s most visited tourist sites, has remained dry for several years.

As this unfolds, rural decline accelerates as irrigation fails, leaving villages effectively depopulated once wells run dry. Younger generations move toward cities or abroad in search of work, weakening traditional agricultural knowledge and local governance networks that once managed shared water. These shifts complicate national planning: Iran’s water strategy has long relied on the idea that a large agricultural sector could support food sovereignty. However, as farms disappear, this idea becomes harder to hold on to, which could force a strategic shift towards relying more on imports.

Agricultural Self-Sufficiency Under Threat

Water scarcity has fundamentally constrained Iran’s longstanding goal of agricultural self-sufficiency. With rivers declining and groundwater aquifers overdrawn, the country can no longer reliably irrigate large areas of farmland. Water-intensive crops such as wheat, rice, and sugar beet now compete for dwindling supplies, and yields are increasingly unpredictable. As a result, Iran struggles to produce enough food to feed its population of some 92 million without turning to imports.

Policies that once prioritized domestic production for strategic and ideological reasons now create tension between national food security objectives and ecological realities. Growing dependence on imported grain and other staplesexposes Iran to global market volatility, amplified by international sanctions on the Iranian banking system, diplomatic pressure from trading partners, and sharply rising domestic prices driven by hyperinflation. These economic pressures further complicate agricultural planning, forcing policymakers to balance strategic self-sufficiency against both environmental limits and escalating costs.

Water as a Tool of Power

Water scarcity does not operate solely within Iran’s borders. Across the broader Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia, water has become intertwined with geopolitics. In the absence of international treaties on rivers (as compared to the high seas, e.g., the 1982 Washington Treaty), water sharing is left to the riparian states to work out among themselves.

Yet, with the colonial past in most of these regions and the relatively new independent statehood of most, water sharing has entered the focus of regional intra-state attention relatively late. Climate change, however, has dramatically increased this necessity, especially as control over headwaters can translate into political bargaining power, and in some cases, states have deliberately used water to pressure neighbors, assert dominance, or influence downstream economic and security outcomes.

A New Geopolitics of Headwaters

Relations between Afghanistan and Iran illustrate how upstream development carries strategic consequences. Tehran views projects on the Helmand River, vital for Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan province, not only as infrastructure but also as assertions of Afghan sovereignty. Each dam threatens reduced flow to Iranian territory, prompting diplomatic strain and, at times, heated rhetoric.

Tensions also surface between Afghanistan and Pakistan over the Kabul River, where future water demand may exceed supply. Beyond irrigation, upstream development has historically been leveraged as a political tool: restricting flow to downstream users can pressure concessions on trade, security, or border negotiations. In these situations, hydrology dictates bargaining power: those who control the flow shape politics. No wonder, under Iran’s new ‘neighborhood policy’, negotiations with both neighbors include water sharing as one of the main topics.

Iran’s Options Narrowing: External Dependence on the Horizon

Self-sufficiency has been an ideological and security principle since 1979, strengthened by the reality of Iran’s general isolation following the Islamic Revolution. Yet current trends indicate that Iran may no longer meet domestic demand without external support. Proposals to import water or expand desalination signal an uncomfortable recognition: sovereignty over food and water may be eroding.

Desalination is expanding along Iran’s southern coast, but infrastructure, energy costs, and environmental implications limit scalability. Meanwhile, importing water from neighboring states introduces geopolitical vulnerability, providing potential strategic advantage for foreign governments to influence Iranian policy. Reliance on external water or agricultural imports is rapidly becoming a strategic discussion point.

Information Gaps and Public Trust

Effective management depends on transparency, but water data in Iran is often treated as confidential. Environmental assessments are rarely shared fully with the public or independent researchers, creating uncertainty about actual conditions.

This opacity encourages speculation. Communities blame mismanagement or regional favoritism; rumors circulate about unauthorized industrial withdrawals or hidden infrastructure failures. Distrust grows faster than credible communication. Institutional capacity exists within Iran to improve water governance, including strong scientific expertise.

The barrier is political: acknowledging the full scale of decline would require renegotiating priorities long framed as essential to national strength. Yet, in response to a call from religious authorities, several organized prayers for water were held across the country.

Climate Change as a Force Multiplier

Climate pressures intensify Iran’s water challenges. Higher temperatures increase evaporation from reservoirs and soil, while reduced snowpack diminishes spring melt feeding rivers. Rainfall has declined by approximately 85% in critical areas, its increasing unpredictability posing serious challenges for both immediate and long-term water resource management. In response, Iran has turned to cloud seeding to induce rainfall, though results remain limited and inconsistent. Extreme weather events, including heatwaves and sudden, localized flooding, further strain rural and urban water infrastructure while also threatening agricultural productivity and food security.

Iran cannot control these climatic drivers, but policy choices determine how severely they affect livelihoods and national security. Failures in governance and resource management amplify these trends, transforming natural variability into full-scale crises. Without coordinated adaptation strategies—ranging from investment in resilient water infrastructure to sustainable agricultural practices—climate change acts as a multiplier for existing vulnerabilities, intensifying rural depopulation, urban water stress, and social unrest.

In this way, environmental shifts do not merely add pressure; they accelerate and exacerbate every underlying economic, political, and infrastructural challenge.

Hydro-Politics and Regional Realignments

Water scarcity is increasingly shaping Iran’s regional relationships, influencing both cooperation and competition. Shared rivers and aquifers create interdependencies that constrain national policy, while scarcity amplifies the stakes of diplomacy, trade, and security. Rather than merely presenting local disputes, these dynamics now shape broader strategic calculations, affecting alliances and regional influence.

Iran faces growing downstream vulnerability and upstream dependency. In the east, tensions over transboundary rivers underscore how upstream development in Afghanistan and Pakistan can affect water availability in Iran’s border provinces, requiring careful negotiation to prevent disruption. In the west, Türkiye’s control of shared water resources limits Tehran’s leverage in Iraq and Syria, forcing Iran to combine technical cooperation, diplomatic engagement, and economic initiatives to maintain influence.

At the same time, Gulf states’ investment in desalination, water recycling, and strategic food reserves introduces asymmetries in water security capabilities, creating new competitive pressures. Scarcity also encourages selective cooperation: multilateral frameworks, cross-border infrastructure projects, and joint drought management programs are increasingly explored, though historical mistrust and diverging national priorities complicate implementation.

These pressures are reshaping strategic flexibility. Where Iran once relied primarily on military, ideological, or economic tools to project influence, hydrological realities now define its options. Access to water flows, control over shared resources, and the capacity to adapt to scarcity have become core determinants of regional bargaining power. In effect, water scarcity functions as both a constraint and a tool, compelling Iran to recalibrate alliances, balance regional competition, and integrate environmental realities into its broader strategic planning.

Water as a Boundary of Strategy

Iran’s water security dilemma demonstrates how environmental realities reshape national priorities. What was once considered a manageable challenge has evolved into a structural constraint affecting agriculture, cities, and foreign policy simultaneously.

Scarcity alters internal migration patterns, raises the likelihood of unrest, and erodes the social contract between state and citizens. Environmental experts and activists, including Nikahang Kowsar—who has been sounding the alarm for nearly two decades—trace much of the crisis to longstanding policies dating back to the reformist era of President Mohammad Khatami, showing how governance decisions interact with natural limits to shape vulnerability.

These pressures demand difficult choices between self-sufficiency and sustainability—choices that carry political risks no matter the direction taken. Beyond Iran’s borders, water scarcity sharpens competition over shared rivers and introduces new factors into regional diplomacy. Access to reliable water flows may determine economic outcomes and future alignments.

The era in which Iran could independently secure its water and food needs is fading. National strategy must now be constructed around hydrological limits rather than in defiance of them. Water, once treated as an input to growth, has become a primary boundary of what Iran can achieve at home and how it can position itself abroad.

About the authors:

Erzsébet N. Rózsa: Professor at Ludovika University of Public Service; Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of World Economics, Hungary.

László Csicsmann: Full Professor and Head of the Centre for Contemporary Asia Studies, Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies (CIAS), Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary; Senior Research Fellow, Hungarian Institute of International Affairs (HIIA).

Source: This article also appeared at Geopolitical Monitor.com