ICYMI

A sweeping internet shutdown across Afghanistan by the Taliban authorities has paralysed cross-border trade and disconnected millions of web users in what has been described as a disaster for the country.

At the Dogharoun border crossing, nearly 800 Iranian and Afghan lorries were stranded mounting further problems with perishable food items beginning to perish in the heat while emergency items including medical supplies were also held up, according to Iranian media.

The blackout stems from a nationwide order issued by Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, who cited the need to combat “immorality” as justification. According to official sources, between 8,000 and 9,000 telecommunications towers have been shut down, and the outage is expected to continue “until further notice.”

The border disruption, which began on the night of September 30, has affected only outbound traffic from Iran, while inbound trucks from Afghanistan continue to enter without issue.

The impact has been far-reaching. Afghanistan’s economy has been severely disrupted, with banking systems, airline operations, and government services grinding to a halt.

Ismail Pourabed, director of the Dogharoun border terminal, confirmed that the outage has severed digital communications with Afghan border authorities, halting customs processing and documentation.

“We are working to resolve the issue by arranging a border meeting with Afghan officials through the Taybad border command,” he said.

Pourabed added that under normal conditions, 600 and 700 trucks exit Iran daily via Dogharoun, with operations running until 11 p.m.

Taliban backtracking on internet outage

The situation at airports is no better with flights operated by carriers such as Ariana and Kam Air cancelled, and citizens have been left unable to contact relatives abroad with mobile signals disconnected.

Following the outcry by Afghans, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid has attributed widespread internet outages across Afghanistan to “worn fibre optic cables,” claiming they are being replaced, Shahrara reported on October 1.

Mujahid claimed old internet fibre optic cables throughout Afghanistan have become worn and are being replaced. He dismissed rumours about Taliban-imposed internet restrictions, saying "rumours are being spread that we have banned the internet".

Internet monitoring organisation NetBlocks confirmed that several networks in Afghanistan have been disconnected and telephone services have been affected, resulting in a complete internet shutdown in the country of 43mn people.

Telecom firms confirm internet shutdown

Telecommunications companies in Afghanistan have confirmed the nationwide internet shutdown was carried out under direct orders from the country's top leadership, Khaama reported on September 30.

Telecom operators said they are merely "managing a sensitive and complex situation" and expressed hope that services may resume soon.

The UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan has expressed grave concern, urging authorities to restore internet access immediately. It warned the blackout has "cut Afghanistan off from the world" and placed people's lives at serious risk.

Richard Bennett, UN special rapporteur on human rights in Afghanistan, stressed on September 30 that without urgent restoration of internet services, daily lives of Afghans, Reuters reported.

He cautioned the blackout is undermining access to education, healthcare and communication for women and girls whilst threatening freedom of expression and access to information.

Tajikistan’s government has remained antagonistic towards Taliban rule in Afghanistan ever since the militant group first appeared some 30 years ago. And in word and deed, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon has shown that he would prefer not to have to deal with his neighbour’s current government at all, though that has proven impossible.

There are ties that bind the two countries. Slowly but surely, the Tajik authorities are developing a relationship with the Taliban that involves cooperation on local levels and goodwill gestures, but avoids, as much as possible, actually speaking with Taliban officials.

Picking up where they left off

Tensions between the Taliban and Tajikistan erupted right after the Taliban’s return to power in mid-August 2021. It was not surprising. Rahmon was also Tajikistan’s president when the Taliban seized power in the mid-1990s, and the two sides were on bad terms back then.

In September 2021, Rahmon ordered, and attended, several military parades held in the weeks after the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan. One was in Darvaz district, right on the Afghan border.

Tajikistan's honouring of assassinated guerilla commander Ahmad Shah Masoud soon after the Taliban retook power is a sore point for the current powers that be in Kabul (© European Union, 1998 – 2025).

At that time, Rahmon also posthumously awarded Afghans Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmad Shah Masoud Tajikistan’s highest award, the Order of Ismoili Somoni, 1st degree.

The Taliban ousted Rabbani when they seized Kabul in late September 1996. Masoud, the legendary mujaheddin fighter from the days of the Soviet occupation, was Rabbani’s defence minister. After he and Rabbani were chased from Kabul, Masoud, an ethnic Tajik, led one of the most effective forces battling the Taliban in the late 1990s. The Taliban assassinated him on September 9, 2001.

Tajikistan served as a conduit for delivering weapons and other supplies to Masoud’s forces in Afghanistan during those days. Masoud and Rabbani were often in Tajikistan for short periods of time.

Rahmon’s presentation of the awards was clearly a jab at the Taliban. Having retaken power, they would also have been aware of reports that Tajikistan was supplying the National Resistance Front (NRF) in Afghanistan with weapons.

The NRF continues to wage a guerrilla war against the Taliban. Most of its fighters are ethnic Tajiks who were part of Ashraf Ghani’s foreign-backed government forces. The NRF is led by Ahmad Masoud, Ahmad Shah Masoud’s son, who, like his father years ago, is also frequently in Dushanbe. In late October 2021, there was a report that the NRF opened an office in the Tajik capital.

Tajikistan reinforced its troops along the Afghan border throughout September 2021.

The Taliban rattled their own sabres, saying in that month that they were dispatching additional special forces to the Tajik border “in order to eliminate potential security threats.”

Among the Taliban’s reinforcements were 130 militants from Jamaat Ansarullah, an extremist group from Tajikistan that allied themselves with the Taliban and joined them in fighting foreign and Afghan government troops. Jamaat Ansarullah’s goal is to topple Rahmon’s government.

By the end of that September, Russia and Pakistan were calling on Tajikistan and the Taliban to lower tensions.

The situation eased, but even now it continues to simmer.

All the other Central Asian governments, meanwhile, established a dialogue with the Taliban, centred mainly on business opportunities.

Taiban representatives occupy Afghan embassies in many countries, including Russia, China, Iran, Pakistan and the Central Asian states, except for Tajikistan. Mohammad Zahir Aghbar remains the Afghan ambassador to Tajikistan. He was appointed to the post in 2020 by the government of Ashraf Ghani. Oddly, however, Taliban representatives occupy the Afghan consulate in Tajikistan’s remote eastern city of Khorog.

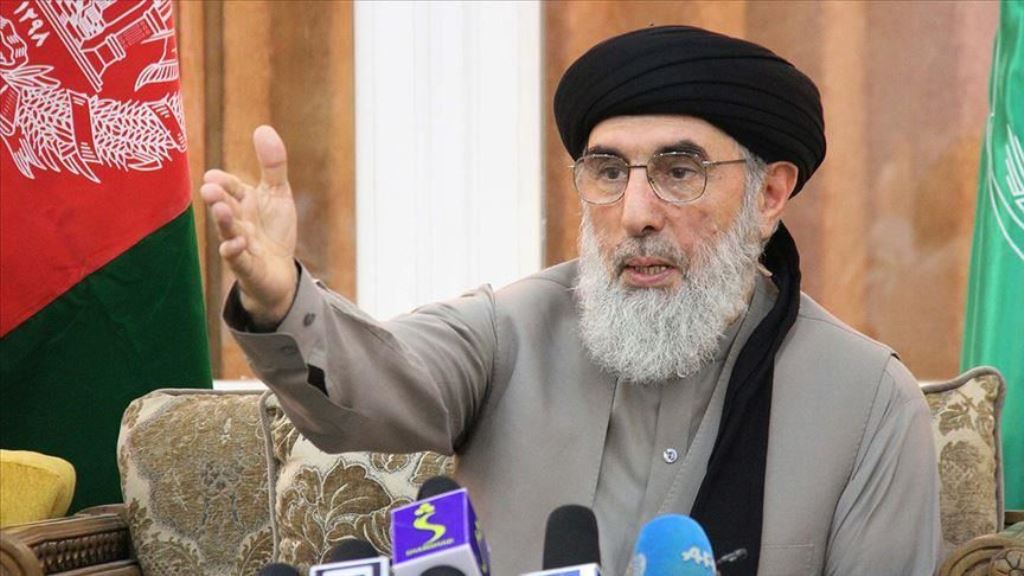

Gulbuddin Hematyar accused Tajikistan of making "a declaration of war against Afghanistan" by giving "shelter" to the NRF (Credit: social media).

In May 2022, Gulbuddin Hematyar, a scourge of Afghanistan’s political world for decades and currently an ally of the Taliban, responded to Tajikistan’s continued support for the NRF. Hekmatyar said the decision of Rahmon’s government to allow the NRF to “shelter” in Tajikistan was a “declaration of war against Afghanistan.”

Tajikistan continues to act against the Taliban internationally.

Since 2012, Afghanistan has had observer status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). The SCO members are Belarus, China, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Since their return to power, the Taliban have not been invited to any SCO meetings.

When the SCO Foreign Ministers’ Council met in May 2024, the topic of resuming the work of the SCO-Afghanistan group was discussed, but rejected. Russia’s special representative for Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, later explained, “Russia and the majority of participants favoured resuming this contact group's work,” but “our Tajik partners still have certain reservations.”

At a session of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization’s (CSTO’s) Council of Parliament Assembly in early June 2024, the chairman of Tajikistan’s upper house of parliament (also the son of Rahmon), Rustam Emomali, warned of the dangers still lurking in Afghanistan.

“Afghanistan has again become a centre of terrorism. Dozens of extremist and terrorist groups have strengthened their positions on Afghan soil,” Emomali claimed, “The cultivation and production of narcotics in Afghanistan is increasing.”

In July this year, Tajikistan’s Drug Control Agency said 3,107 kilograms of narcotics were seized in the first half of 2025 and “54.4 percent of these narcotics were seized at the border with Afghanistan.”

Elements of common ground

Tajik electricity exports to Afghanistan were not interrupted by the change in Kabul. The cash-strapped Tajik government did not want to give up the revenue from electricity sales. It was even willing to accept a Taliban promise of eventual payment rather than halt exports.

Eventually the Taliban did pay their bill and in December 2024, Tajikistan and Afghanistan renewed their electricity supplies agreement through 2025. Such a contract must require some level of bilateral communication, but the Tajik government never mentions such interaction.

Power lines running from Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan to Afghanistan were built during the years the Taliban was out of power. Also, the World Bank announced in February 2024 that construction of the Central Asia-South Asia (CASA-1000) power transmission line, started more than a decade ago, had resumed in Afghanistan after it was halted when the Taliban regained control there.

CASA-1000 aims to bring 1,300 MW of electricity from hydropower plants in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pakistan (300 MW to Afghanistan and 1,000 MW to Pakistan). The project is complete in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan. Afghanistan’s Ministry of Energy said in March that work on CASA-1000 in Afghanistan was 70% completed. Afghanistan’s Ministry of Economy said at the start of April that work on the Afghan section of CASA-1000 was expected to be finished by 2027.

Security is another area that brings Tajikistan and the Taliban together.

Rocket fire from Islamic State of Khorasan Province

Tajik authorities were first compelled to make contact with the Taliban in May 2022 after militants from the Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP, or ISIS-K) fired several rockets from Afghanistan into Tajikistan. There was little damage but the incident prompted the Tajik government to send former security officer Samariddin Chuyanzoda to Kabul. More than two years later, Tajik national security chief Saymumin Yatimov visited the Afghan capital in September 2024.

Keeping it cordial – events in 2025 offer some hope

This year has brought a change in relations between Tajikistan and the Taliban.

In January, the latter’s Deputy Prime Minister for Political Affairs, Maulvi Abdul Kabir, observed that the Sherkhan Bandar border crossing with Tajikistan was open. He said it was a sign of improving cooperation.

In May, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said there were no problems between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. According to Mujahid, “Afghanistan maintains good relations with [Tajik] border officials on the other side and cooperation has taken place—and continues—in preventing smuggling in certain areas.”

However, Mujahid mentioned that “friendly ties must be maintained, especially with Tajikistan, where political opponents of the Islamic Emirate are based. This makes it vital Afghanistan-Tajikistan relations remain cordial."

Not long after, Abdul Bari Omar, head of Afghanistan’s state power utility Da Afghanistan Breshna Sherkat (DABS), attended a meeting of representatives from CASA-1000 countries in Dushanbe.

An earthquake that hit Afghanistan on August 31 killed around 2,200 people and left hundreds of thousands in need of help. Neighbouring countries sent humanitarian aid. Uzbekistan shipped 300 tonnes of food, medicines, and medical supplies, and Turkmenistan dispatched unspecified amounts of similar aid. A few days later, Tajikistan sent 3,000 tonnes of food, tents, blankets and construction materials.

Tajikistan's aid delivery following the deadly end-of-August earthquake that hit Afghanistan was a notable gesture in relations (Nangarhar Governor's Office, official handout).

Since the Taliban re-established their rule, all the Central Asian countries except Tajikistan have sent humanitarian aid in response to earthquakes, floods, droughts and famine, which grips large parts of Afghanistan.

The only time Tajikistan sent aid to Taliban-ruled Afghanistan previously was after an October 2023 earthquake.

Ironically, a recent deadly incident on the Tajik-Afghan border might offer the clearest proof that relations between Kabul and Dushanbe are improving.

On August 24, Tajik border guards and Taliban fighters exchanged gunfire. At least one of the Taliban was killed, while four others were wounded.

Armed clashes between Tajik border guards and Afghan drug smugglers, some of whom can be Taliban, have occurred for decades. But Tajik troops and Taliban fighters on the border have avoided firing at each another.

What sparked the August 24 conflict is not clear. If this incident had happened in September 2021, the fighting would likely have escalated quickly. Instead, the Tajik border guard commander took a small detachment of troops and went into Afghanistan to meet with local officials to discuss the clash. A photo shows the various parties sitting at a table.

The talks eventually deteriorated into accusations from each side over the harbouring of enemies. But the meeting appears to have at least defused tensions between the two groups in this one area of the 1,357-kilometre (843-mile) Tajik-Afghan border.

The relationship between Tajikistan and the Taliban is a strange one. Neither side trusts the other and there is only contact when the need arises, but lately the need to communicate about mutual problems has been increasing.

No comments:

Post a Comment