Indonesia tightens grip on resources with Switzerland-sized land grab

It started in earnest in March, with a swath of palm-oil estates seized from a tycoon caught up in corruption allegations. Nine months later, a drive overseen by Indonesia’s defense minister has brought an area the size of Switzerland under state control.

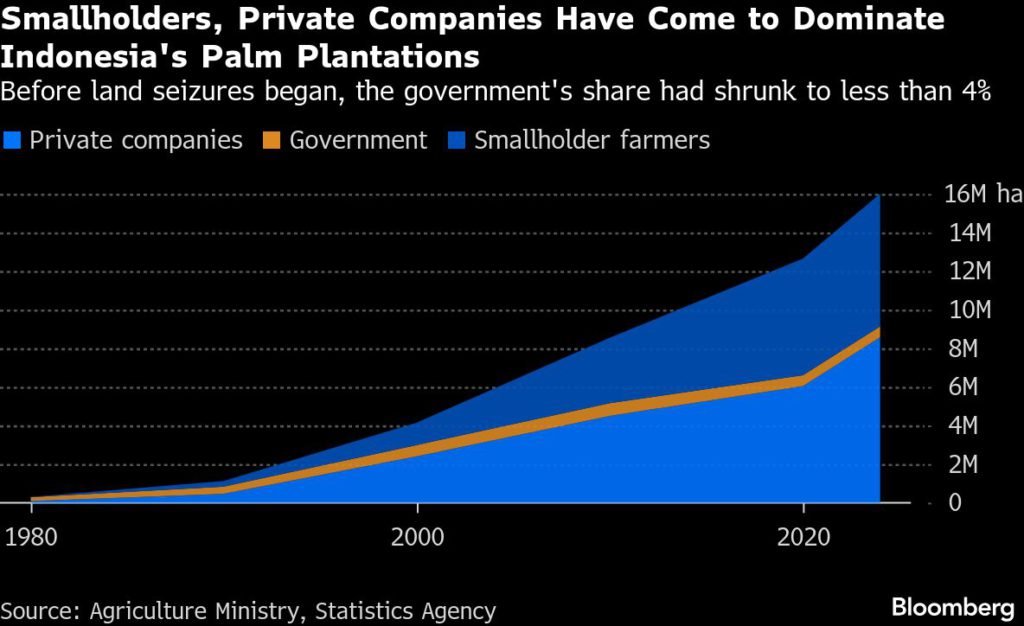

The campaign, outwardly a push to improve governance, is a show of force by President Prabowo Subianto, an ex-general who has regularly railed against both Indonesian elites and foreigners for profiting off the country’s resource riches at the expense of the nation. Already, the central government has taken more than 4 million hectares (roughly 10 million acres) of plantations, mine concessions and processing facilities — and much of that land has been handed to a state-owned firm newly tasked with managing seized estates.

“This is just the beginning,” Prabowo said at an event late last month. “We are on the right and noble path of defending the interests of millions of Indonesians.”

Domestic upheaval could soon have global consequences. Indonesia is the world’s top exporter of coal and palm oil, the biggest nickel producer and a leading source of copper and tin — commodities key for food and energy supplies, as well as future-facing technologies.

“This increasingly shows the character of a Prabowo-style command economy,” said Bhima Yudhistira Adhinegara, executive director at the Jakarta-based Center of Economic and Law Studies. “Methods like this reduce interest from investors, both in the plantation sector and in conservation,” he said.

Prabowo established the Forest Area Enforcement Task Force last January, only months into his tenure. At the helm he placed Defense Minister Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin, a longtime ally who has known the president since his early days in the military.

The task force issues fines and transfers land, frequently to the state-owned giant at the heart of the effort, Agrinas Palma Nusantara. In a matter of months, this repurposed company led largely by retired military officers has become the world’s biggest palm oil player by area held.

To date, official pronouncements on the confiscations have focused on better land management, an area where Indonesia has not always excelled — the country has lost millions of hectares of forest in recent years, much of it because of palm-oil and mining expansion. The role of deforestation in worsening floods and landslides that killed more than 1,000 people in Sumatra last month has added momentum to Jakarta’s campaign.

But growers in the government’s sights say they are farming land that was bought, or in some cases handed to them years earlier under government programs to encourage internal migration.

Prabowo “claims that the state has reclaimed 4 million hectares because these plots were located within forest zones,” said Achmad Sukarsono at consultancy Control Risks. “But how did it come to this? Such a vast amount of land couldn’t have been taken illegally by palm oil companies without approval from local governments and military officials.”

Agrinas and Sjamsoeddin’s task force did not respond to Bloomberg queries.

For generations, Rubahan Hasibuan’s family and those of his neighbors have been working the same land in northern Sumatra, today one of the nation’s main palm-growing areas. Back in March, some 20 to 30 officials arrived in his village of Ujung Gading Julu. Many wore uniforms from the military and prosecutor’s office, he later recalled.

The forestry task force posted a sign on a nearby plantation, declaring the land to be under government control. About 2,000 hectares of farmland in the village, owned by roughly 500 families, were seized, he said. He and his neighbors have since met with officials four times and have been offered the option of staying on their land in exchange for a cut of the profits.

Agrinas has proposed allowing farmers to stay in exchange for a 15% share of revenue, but the group has resisted.

“We turned it down to keep our independence,” the 48-year-old said, speaking at the governor’s office in the provincial capital of Medan, having driven 11 hours to seek backing from local officials. “We planted the trees, and we worked hard to take care of them.”

For now, they are still farming, Hasibuan said, though the city meetings ultimately proved fruitless. No one in the group knew how long they could continue.

“We will not give up,” he said.

Tighter control of domestic resources has been a vital concern for the Prabowo administration, in part to fund an ambitious but costly policy program. He has also pledged to protect ordinary people from what he calls “greedy-nomics,” the actions of business elites who relentlessly pursue maximum profit.

The campaign gained momentum in March, with the handover of 221,000 hectares from Duta Palma Group, a palm oil firm owned by Surya Darmadi, formerly one of the country’s richest men and more recently the subject of a money laundering and corruption probe. Since, plantations have been targeted across the archipelago, as well as a half dozen tin smelters and a portion of the world’s largest nickel mine.

About four dozen palm companies have been ordered to pay a total of around $560 million, while 22 miners were ordered to pay more than $1.7 billion as a way to return what the government says are illegal gains to the state, according to figures provided by the Indonesian attorney general’s office.

The impact is already rippling beyond Indonesia. Singapore-based crop trader Wilmar International Ltd. has said it expects a few thousand hectares of its plantation area to be impacted and is in discussion with authorities, according to a spokesperson. Malaysian-listed IOI Corporation Bhd., which operates palm plantations and mills in Kalimantan, will now undertake more risk assessments before investments in Indonesia, according to chief executive officer Lee Yeow Chor. First Resources Ltd. and SD Guthrie Bhd. declined to comment.

Other major palm oil operators, including Golden Agri-Resources Ltd., Cargill Inc. and state-owned PT Perkebunan Nusantara III, did not respond to Bloomberg queries on the seizures. The Indonesian Mining Association and Indonesia Nickel Miners Association didn’t reply to requests for comment.

Changing regulations are not new for Indonesia’s commodities sector, nor are unclear permits. Overlapping land allocations are common in palm oil, where some areas are permitted for cultivation though they are still classified as forest areas, said Tungkot Sipayung, executive director of the Palm Oil Agribusiness Strategic Policy Institute. One veteran plantation owner working in Sumatra, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue, expressed frustration that even a plot farmed for decades, bought from other farmers, could now be said by officials to be on forest land.

Mining suffers similar problems, as the government struggles to monitor illegal mining in vast tracts of land in some of the country’s most remote areas. These illicit operations have cost Indonesia billions, Prabowo said in his first State of the Nation address.

The campaign’s breadth has echoes of the nationalizations and dramatic reorganization of property under Indonesia’s first president after the end of the colonial era, said Eve Warburton of Australian National University, who works on governance and resource nationalism in Indonesia. But the clean-up is also being led by a task force with a great deal of discretion in terms of who it goes after, when and why.

“The risk of politicization is high,” said Warburton. “This can undermine investor confidence and the credibility of resources governance more broadly.”

For commodity companies, the past months have already jangled nerves as they reckon with the impact of new state players.

According to Agrinas and the attorney general, it now holds 1.7 million hectares of plantations. It aims to supply a third of Indonesia’s cooking oil and begin producing biodiesel by 2029.

Much of that vast land bank isn’t yet productive — less than half is already planted with trees, Agrinas President Director Agus Sutomo told parliament in September. The portfolio also includes a plethora of small plots that individually lack the scale to be cultivated efficiently. Managing it will require vast investment in land restoration and productivity.

What that means in the short term is that it needs to bring farmers onside. Many growers on seized properties are still working the land, as in Hasibuan’s village in Sumatra.

But, as for those farmers, conditions for what Agrinas calls joint operations are not always appealing. Growers are allowed to keep only about 55% to 60% of revenue, with the rest handed to the state player, according to a corporate presentation. The share for smallholders can be higher — but not always high enough to encourage the compromise.

As a result, some farmers are walking away from seized areas. Others, facing little choice, agreed to joint ventures with the state, according to officials from two palm companies, who declined to be named. For those who stayed, costly replanting — vital to maintaining crop yields over time — has often been put on hold.

Industry group Gapki has heard complaints from members that harvest proceeds are fully directed to Agrinas’s account, with payments to partners made more than 30 days later, according to a closed-door presentation made to parliament, later seen by Bloomberg. Gapki did not respond to Bloomberg queries.

Similar scenes have unfolded in mining. On Halmahera, an island in the far northeast of Indonesia’s archipelago, soldiers arrived alongside a TV crew in September alleging violation of a forestry permit by the world’s biggest nickel mine. Only 148 hectares of the 45,000-hectare site owned by PT Weda Bay Nickel were seized, but the threat briefly pushed up global prices.

According to a person familiar with the matter, the government is demanding a penalty of around 3 trillion rupiah ($179 million) from the firm, whose largest shareholder is Tsingshan Holding Group Co. — a Chinese heavyweight that spearheaded metals investment in Indonesia and transformed the industry. A spokesperson for WBN said the company complies with authorities and was running checks on the fines.

It’s not clear where Prabowo’s campaign goes from here. Enforcement and long-term management is more challenging than the initial seizures, especially in a country as expansive as Indonesia. For now, benchmark palm oil futures are trading not far off a six-month low, suggesting the wider market is not yet worried about production — while broad supply concerns are only starting to filter into the nickel market.

But at one of the palm industry’s biggest gatherings in Bali in November, concern over long-term consequences of seizures and fines permeated conversations.

According to a formula laid out by the government, growers will face a charge of $1,497 per hectare for every year since land clearing began, aside from a five-year exemption to account for the time it takes for oil palms to become productive. That could leave companies facing penalties heftier than the value of their land, the Sumatra plantation owner said.

For nickel miners, the rate was set at $389,000 per hectare — enough to bankrupt many of the small companies who still dominate output, according to two miners caught up in the situation. Coal, bauxite and tin miners face smaller penalties. Barita Simanjuntak, an expert at the attorney general’s office, said the government’s internal auditor calculated the fines using established formulas.

“The risk that production will suffer more than we dare to say now is probably bigger than vice versa,” Thomas Mielke, executive director of Oil World and leading palm industry analyst said at the Bali event. “This is a very critical and very sensitive situation.”

(By Eko Listiyorini and Eddie Spence)

No comments:

Post a Comment