The republic on trial: Militarised sovereignty and accountability in Kashmir

On the night of February 23–24, 1991, soldiers of the 4th Rajputana Rifles entered the villages of Kunan and Poshpora in Kupwara district in what was described as a routine cordon-and-search operation. By that point, such operations had become embedded in everyday life across Kashmir.

Villages were sealed. Men were assembled outdoors for identification. Homes were searched through the night. The stated objective was counterinsurgency. The practical effect was the visible performance of state authority in a territory where sovereignty was under open challenge.

By morning, women in the two villages alleged that soldiers had entered their homes after separating the men and subjected them to sexual assault. The scale of the accusations was significant. The army denied the charges.

Senior officials characterised the accusations as fabricated, implying that their purpose was to undermine counterinsurgency operations. Local police registered a First Information Report. A medical examination was conducted.

The case entered the formal register of the criminal justice system. Investigations followed. Reports questioned the credibility of the allegations. A closure report was eventually filed. No full criminal trial ever tested the evidence in open court.

That absence is the defining feature of the case. Not conviction. Not acquittal. Not adversarial adjudication. No criminal courtroom has examined the allegations through cross-examination, evidentiary scrutiny and judicial determination for more than three decades. They have remained administratively contained.

Counterinsurgency as governance

To understand why, the events must be situated in the early 1990s, when armed insurgency in Kashmir escalated sharply, as demands for self-determination moved from protest to armed movements.

The Indian state responded with a heavy troop deployment and institutionalised counterinsurgency as a governing framework. Emergency powers were not exceptional interventions; they became routine instruments of rule.

Counterinsurgency is often described as a military doctrine. In practice, it is a political order. It regulates mobility, domestic space, speech and suspicion. It redraws the boundary between civilian and suspect.

Armed personnel physically enact sovereignty when they seal entire villages overnight and search households. Authority does not simply exist; it is staged.

In that setting, claims of sexual abuse have ramifications that extend beyond personal misconduct. They propose that the coercive rationale of counterinsurgency may have infiltrated personal domains. Sexual violence in conflict situations is not just assault; it shows who is in charge.

The state’s immediate response was denial, followed by investigative framing that foregrounded insurgency conditions and questioned credibility. From the outset, the case became entangled in a broader struggle over narrative: was Kashmir a site of necessary security operations, or a site where civilians were exposed to unchecked force?

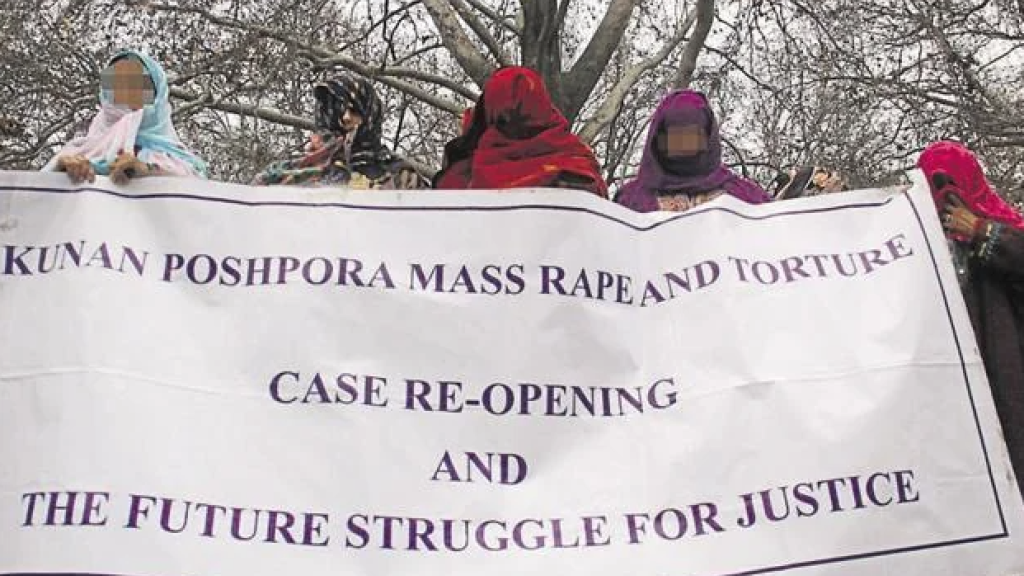

Survivors and activists pursued reinvestigation through courts and petitions. The matter resurfaced periodically. But it never matured into a decisive judicial reckoning. The unresolved status hardened into a structural outcome. Kunan and Poshpora endure because they reveal the internal tensions of militarised governance.

When emergency powers become the grammar of rule, accountability narrows. The issue extends beyond the events of that night. It concerns how democracies respond when allegations implicate the coercive institutions tasked with defending territorial integrity.

The issue is of serious importance for Indian democracy. Undoubtedly, a democracy that is confident in its institutions is willing to subject them to scrutiny. A democracy that hesitates signals a different priority: preserving the apparatus before testing it.

AFSPA and immunity

The unresolved status of Kunan and Poshpora cannot be understood without examining the legal regime governing Kashmir. At the centre of that regime stands the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA).

AFSPA authorises armed forces operating in “disturbed areas” to arrest without warrant, conduct searches and use force under broad conditions. Most consequentially, it requires prior sanction from the central government before any prosecution of armed forces personnel can proceed in civilian courts. Without that sanction, criminal proceedings cannot begin.

In theory, this provision is presented as protection for soldiers operating in high-risk environments. In practice, it has functioned as a structural bottleneck. Allegations against armed forces personnel remain contingent on executive approval, significantly limiting judicial autonomy in initiating proceedings.

In the wake of the Kunan and Poshpora allegations, investigations were initiated and a closure report generated, although survivors sought further reinvestigation. The legal proceedings encountered obstacles, primarily the sanction requirement, preventing the case from reaching a trial.

AFSPA embeds counterinsurgency logic within statutory law, altering legal priorities in disturbed regions and relaxing operational constraints on security forces. While defenders of the act maintain that such legal protections are essential to prevent debilitating litigation against soldiers, this narrative must not absolve the necessity of accountability.

Allegations of serious crimes should undergo transparent processes, rather than be obstructed by routine sanction clauses, which foster "immunity by design." This procedural impunity, though not formally declared, cultivates perceptions within communities that certain actors operate beyond judicial scrutiny.

The Kunan and Poshpora cases underscore the impact of emergency legislation on democratic accountability, wherein legal structures intended to curb power paradoxically become instruments of shielding it.

The central issue transcends operational freedom for soldiers; it questions the legitimacy of a democracy that permits executive discretion in determining accountability for its own agents.

Gendered power in a militarised territory

It is easy for the discussion about Kunan and Poshpora to get mired in controversies about facts, figures, accounts and inconsistencies. But the underlying level is just as important: how sexual violence works in a militarised setting to maintain a hierarchy that favours the powerful.

Cordons and searches blur the distinction between public and private. Men are assembled outside; women remain inside; armed forces enter homes under the guise of the law. The home ceases to be a safe haven and becomes a site of surveillance and domination. Power enters the domain of the intimate.

Civil society reports, including documentation by the Jammu-Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, have identified numerous cases of sexual violence linked to the conflict and have argued that legal immunity structures enable such abuses.

In a patriarchal world, the social implications of sexual violence are exponentially greater. A woman’s body is inextricably bound to her family's honour and the community’s identity. An act of violence has repercussions that reverberate beyond the survivor — shaking kinship, conjugal prospects and social status. Stigma multiplies the pain. Silence can be a shield, even as it conceals the injury.

This narrative plays out in the way charges are treated. Victims are confronted with both state power and social coercion. To speak out is to invite ostracism; to remain silent is to retain social status at the expense of justice. When women in Kunan and Poshpora turned to the law for redress, they challenged both militarised power and the social norms that regulate speech in their society.

The state’s response follows the usual pattern in war zones. Allegations are couched in terms of exaggeration or political motivation. In insurgency situations, allegations of abuse are frequently restated as disinformation. The onus is on the complainant to demonstrate injury and establish noble intentions.

However, emergency governance heightens gendered vulnerability. Armed men possess legal sanction, mobility and impunity; civilian women do not have a comparable level of leverage. Even in the absence of policy, the asymmetry creates risks.

Kunan and Poshpora remain important because they highlight this asymmetry. They expose how counterinsurgency obscures the distinction between security operation and social regulation.

The political question is not confined to the truth of individual allegations. It concerns whether emergency regimes adequately protect bodily autonomy. If domestic space becomes penetrable under state authority and allegations of abuse remain untested in court, then vulnerability is structural, not episodic.

Exceptional law and unequal citizenship

The Indian Constitution officially guarantees the principles of equal treatment before the law, due process, and judicial remedies against state wrongdoing. These principles form the normative foundation of republican legitimacy, under the assumption that independent courts can effectively check abuses of state power, regardless of their magnitude.

In regions governed under prolonged emergency legislation, that equilibrium shifts. The formal architecture of constitutional rights remains intact, but its operational character changes. The requirement of executive sanction before prosecuting armed forces personnel introduces an additional layer between allegation and adjudication. Legal accountability becomes conditional on administrative approval.

Kunan and Poshpora exemplify this structural tension. In ordinary criminal law, the filing of a First Information Report and the collection of evidence can culminate in trial if prosecutorial thresholds are met. In Kashmir, under AFSPA, the path from accusation to courtroom is mediated by executive discretion. The effect is not the suspension of the law but rather its recalibration in favour of operational protection.

This recalibration alters the citizen–state relationship. Constitutional equality presumes that public officials and civilians stand before the same judicial forums when accused of grave crimes. Where prior sanction operates as a gatekeeping device, that presumption weakens. Even when legally authorised, the appearance of differential accountability carries political consequences.

The 2019 reorganisation of Jammu and Kashmir into Union Territories intensified this contradiction. The stated objective was integration and normalisation. Yet the legal instruments that institutionalise exceptional security governance remain largely unchanged. Political autonomy contracted while emergency frameworks endured. The assurance of constitutional uniformity exists alongside differentiated layers of accountability.

Legitimacy in a democracy rests not only on territorial control but institutional credibility. Public confidence in procedural equality erodes when serious allegations against state agents fail to reach open judicial examination. The issue extends beyond the reputation of the armed forces. It concerns systemic questions: whether constitutional guarantees operate with the same force in frontier spaces as they do elsewhere.

A republic with strong institutions allows for scrutiny, especially when coercive power is at its highest. Shielding institutions from prosecution may preserve short-term operational strategies, but it carries long-term costs for constitutional trust. The persistence of unresolved cases such as Kunan and Poshpora underscores the tension between emergency governance and equal justice.

The republic on trial

Kunan and Poshpora cannot be treated as an aberration or tragic residue of a turbulent decade. What followed 1991 was not administrative drift; it was the structured outcome of a state that chose insulation over scrutiny.

The long refusal to subject grave allegations to open trial reflects not institutional weakness but a political priority: preserving the coercive apparatus deemed essential to governing a contested territory.

At stake is not only justice for survivors. It is the character of the Indian state under conditions of internal conflict. Modern states claim a monopoly over legitimate violence. In democratic theory, that monopoly is justified by law, equality and accountability.

But when the institutions that exercise sovereign force are shielded from ordinary judicial testing, sovereignty begins to detach from democracy. It becomes managerial, securitised and increasingly insulated from popular scrutiny.

AFSPA is not merely an emergency statute. It is an expression of how the state manages peripheral regions, where consent is fragile. In such spaces, coercion is normalised and legal exceptions become routine.

While executive sanction regimes are defended as operational necessities, in practice, they produce stratified citizenship. One legal order for the core, another for the frontier where sovereignty is enforced through prolonged militarisation.

This hierarchy bears significant political implications. It indicates that the priorities of territorial integrity and strategic control take precedence over equal justice. It implies to citizens residing in militarised zones that constitutional guarantees are conditional and subject to security considerations.

Over time, such behaviour corrodes the ideological claim that the state represents a unified democratic community. Compliance may persist but political legitimacy erodes significantly.

From our perspective, the issue is not simply a question of procedural reform. It exposes the deeper logic of a state that defends property, territory and geopolitical standing with extraordinary powers while narrowing democratic accountability. Legal exceptionalism at the margins reshapes the centre, rarely limiting militarised governance to its original theatre.

Accountability, therefore, is not a liberal luxury. It is a material question of power. Either the armed apparatus of the state remains subject to the same judicial processes as the citizens it governs or a differentiated sovereignty takes root — one that reserves immunity for those who wield force in its name.

What would accountability entail? Enforced limits on executive sanction, independent prosecutorial authority in areas under emergency law, and sustained legislative review of exceptional security regimes are the minimum requirements for accountability.

But more fundamentally, it requires rejecting the premise that security and equality are mutually exclusive. A democratic state confident in its social foundations does not fear judicial scrutiny of its own agents.

Thirty-five years on, the unresolved status of Kunan and Poshpora is not merely a legal anomaly. It is a political marker. It reveals the tension between a constitutional promise of equal citizenship and a governing practice that privileges militarised order.

Until allegations of this magnitude are tested in open court, that contradiction remains active — a reminder that sovereignty without accountability drifts toward domination and that democracy without equality becomes rhetoric.

No comments:

Post a Comment