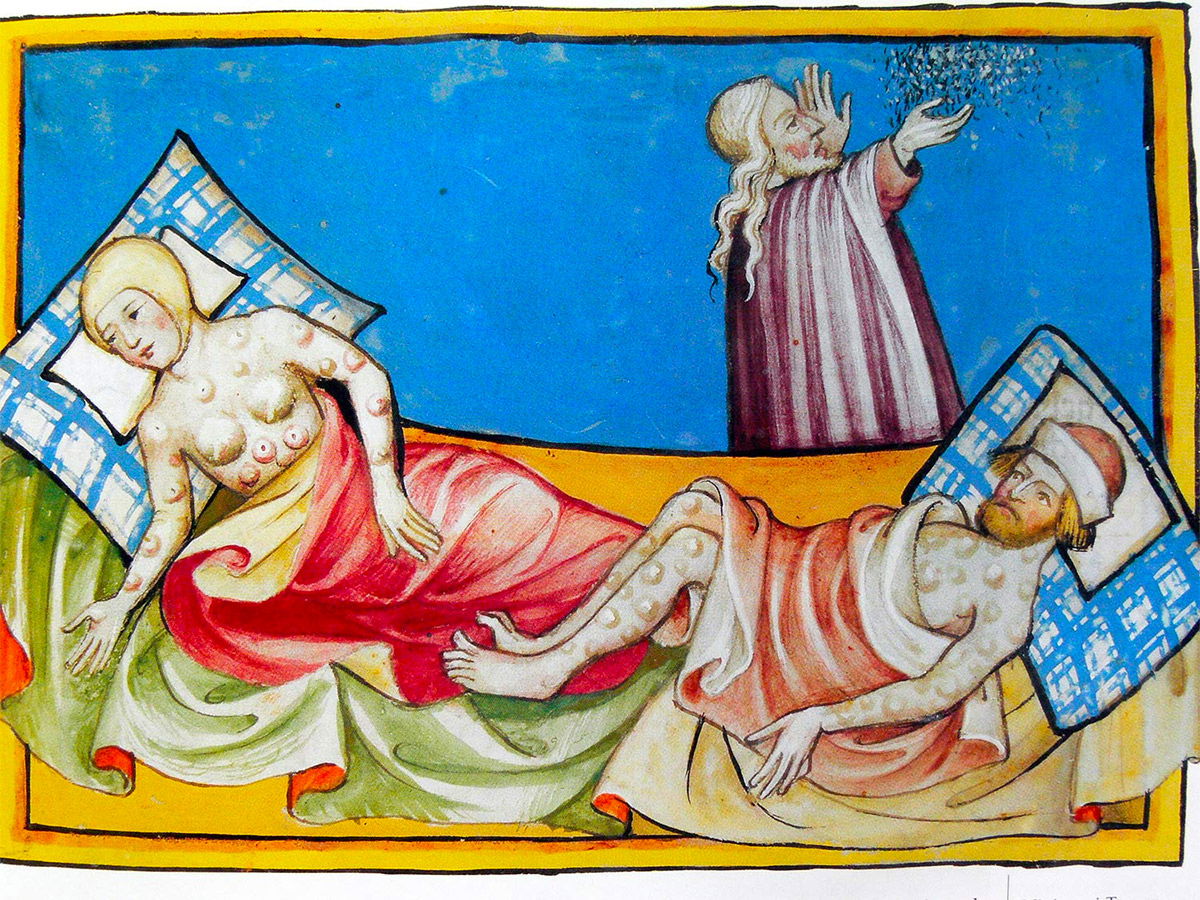

Miniature out of the Toggenburg Bible (Switzerland) of 1411.

The disease is widely believed to be the plague, although the location

of bumps and blisters is more consistent with smallpox.

The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever

Ole J. Benedictow describes how he calculated that the Black Death killed 50 million people in the 14th century, or 60 per cent of Europe’s entire population.

The disastrous mortal disease known as the Black Death spread across Europe in the years 1346-53. The frightening name, however, only came several centuries after its visitation (and was probably a mistranslation of the Latin word ‘atra’ meaning both ‘terrible’ and ‘black)’. Chronicles and letters from the time describe the terror wrought by the illness. In Florence, the great Renaissance poet Petrarch was sure that they would not be believed: ‘O happy posterity, who will not experience such abysmal woe and will look upon our testimony as a fable.’ A Florentine chronicler relates that,

All the citizens did little else except to carry dead bodies to be buried [...] At every church they dug deep pits down to the water-table; and thus those who were poor who died during the night were bundled up quickly and thrown into the pit. In the morning when a large number of bodies were found in the pit, they took some earth and shovelled it down on top of them; and later others were placed on top of them and then another layer of earth, just as one makes lasagne with layers of pasta and cheese.

The accounts are remarkably similar. The chronicler Agnolo di Tura ‘the Fat’ relates from his Tuscan home town that

... in many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead [...] And there were also those who were so sparsely covered with earth that the dogs dragged them forth and devoured many bodies throughout the city.

The tragedy was extraordinary. In the course of just a few months, 60 per cent of Florence’s population died from the plague, and probably the same proportion in Siena. In addition to the bald statistics, we come across profound personal tragedies: Petrarch lost to the Black Death his beloved Laura to whom he wrote his famous love poems; Di Tura tells us that ‘I [...] buried my five children with my own hands’.

The Black Death was an epidemic of bubonic plague, a disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis that circulates among wild rodents where they live in great numbers and density. Such an area is called a ‘plague focus’ or a ‘plague reservoir’. Plague among humans arises when rodents in human habitation, normally black rats, become infected. The black rat, also called the ‘house rat’ and the ‘ship rat’, likes to live close to people, the very quality that makes it dangerous (in contrast, the brown or grey rat prefers to keep its distance in sewers and cellars). Normally, it takes ten to fourteen days before plague has killed off most of a contaminated rat colony, making it difficult for great numbers of fleas gathered on the remaining, but soon- dying, rats to find new hosts. After three days of fasting, hungry rat fleas turn on humans. From the bite site, the contagion drains to a lymph node that consequently swells to form a painful bubo, most often in the groin, on the thigh, in an armpit or on the neck. Hence the name bubonic plague. The infection takes three–five days to incubate in people before they fall ill, and another three–five days before, in 80 per cent of the cases, the victims die. Thus, from the introduction of plague contagion among rats in a human community it takes, on average, twenty-three days before the first person dies.

When, for instance, a stranger called Andrew Hogson died from plague on his arrival in Penrith in 1597, and the next plague case followed twenty-two days later, this corresponded to the first phase of the development of an epidemic of bubonic plague. And Hobson was, of course, not the only fugitive from a plague-stricken town or area arriving in various communities in the region with infective rat fleas in their clothing or luggage. This pattern of spread is called ‘spread by leaps’ or ‘metastatic spread’. Thus, plague soon broke out in other urban and rural centres, from where the disease spread into the villages and townships of the surrounding districts by a similar process of leaps.

In order to become an epidemic the disease must be spread to other rat colonies in the locality and transmitted to inhabitants in the same way. It took some time for people to recognize that a terrible epidemic was breaking out among them and for chroniclers to note this. The timescale varies: in the countryside it took about forty days for realisation to dawn; in most towns with a few thousand inhabitants, six to seven weeks; in the cities with over 10,000 inhabitants, about seven weeks, and in the few metropolises with over 100,000 inhabitants, as much as eight weeks.

Plague bacteria can break out of the buboes and be carried by the blood stream to the lungs and cause a variant of plague that is spread by contaminated droplets from the cough of patients (pneumonic plague). However, contrary to what is sometimes believed, this form is not contracted easily, spreads normally only episodically or incidentally and constitutes therefore normally only a small fraction of plague cases. It now appears clear that human fleas and lice did not contribute to the spread, at least not significantly. The bloodstream of humans is not invaded by plague bacteria from the buboes, or people die with so few bacteria in the blood that bloodsucking human parasites become insufficiently infected to become infective and spread the disease: the blood of plague-infected rats contains 500-1,000 times more bacteria per unit of measurement than the blood of plague-infected humans.

Importantly, plague was spread considerable distances by rat fleas on ships. Infected ship rats would die, but their fleas would often survive and find new rat hosts wherever they landed. Unlike human fleas, rat fleas are adapted to riding with their hosts; they readily also infest clothing of people entering affected houses and ride with them to other houses or localities. This gives plague epidemics a peculiar rhythm and pace of development and a characteristic pattern of dissemination. The fact that plague is transmitted by rat fleas means plague is a disease of the warmer seasons, disappearing during the winter, or at least lose most of their powers of spread. The peculiar seasonal pattern of plague has been observed everywhere and is a systematic feature also of the spread of the Black Death. In the plague history of Norway from the Black Death 1348-49 to the last outbreaks in 1654, comprising over thirty waves of plague, there was never a winter epidemic of plague. Plague is very different from airborne contagious diseases, which are spread directly between people by droplets: these thrive in cold weather.

This conspicuous feature constitutes proof that the Black Death and plague in general is an insect-borne disease. Cambridge historian John Hatcher has noted that there is ‘a remarkable transformation in the seasonal pattern of mortality in England after 1348’: whilst before the Black Death the heaviest mortality was in the winter months, in the following century it was heaviest in the period from late July to late September. He points out that this strongly indicates that the ‘transformation was caused by the virulence of bubonic plague’.

***

Another very characteristic feature of the Black Death and plague epidemics in general, both in the past and in the great outbreaks in the early twentieth century, reflects their basis in rats and rat fleas: much higher proportions of inhabitants contract plague and die from it in the countryside than in urban centres. In the case of English plague history, this feature has been underlined by Oxford historian Paul Slack. When around 90 per cent of the population lived in the countryside, only a disease with this property combined with extreme lethal powers could cause the exceptional mortality of the Black Death and of many later plague epidemics. All diseases spread by cross-infection between humans, on the contrary, gain increasing powers of spread with increasing density of population and cause highest mortality rates in urban centres.

Lastly it could be mentioned that scholars have succeeded in extracting genetic evidence of the causal agent of bubonic plague, the DNA-code of Yersinia pestis, from several plague burials in French cemeteries from the period 1348-1590.

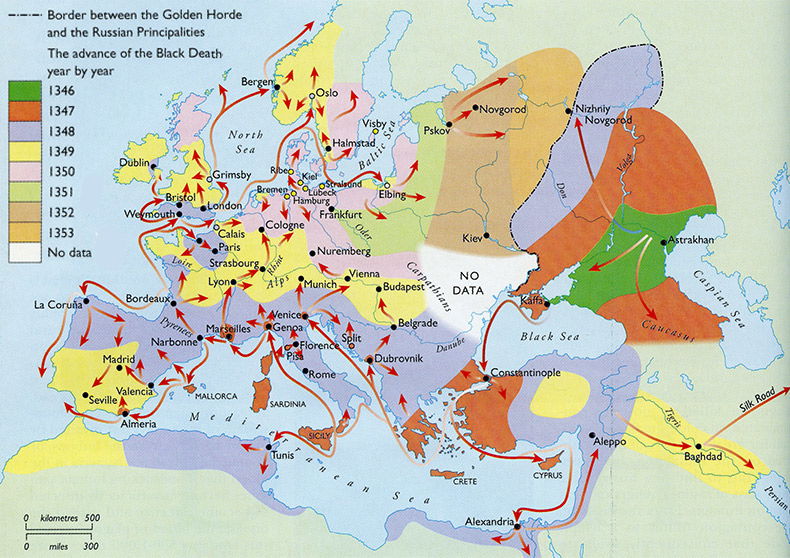

It used to be thought that the Black Death originated in China, but new research shows that it began in the spring of 1346 in the steppe region, where a plague reservoir stretches from the north-western shores of the Caspian Sea into southern Russia. People occasionally contract plague there even today. Two contemporary chroniclers identify the estuary of the river Don where it flows into the Sea of Azov as the area of the original outbreak, but this could be mere hearsay, and it is possible that it started elsewhere, perhaps in the area of the estuary of the river Volga on the Caspian Sea. At the time, this area was under the rule of the Mongol khanate of the Golden Horde. Some decades earlier the Mongol khanate had converted to Islam and the presence of Christians, or trade with them, was no longer tolerated. As a result the Silk Road caravan routes between China and Europe were cut off. For the same reason the Black Death did not spread from the east through Russia towards western Europe, but stopped abruptly on the Mongol border with the Russian principalities. As a result, Russia which might have become the Black Death’s first European conquest, in fact was its last, and was invaded by the disease not from the east but from the west.

The epidemic in fact began with an attack that the Mongols launched on the Italian merchants’ last trading station in the region, Kaffa (today Feodosiya) in the Crimea. In the autumn of 1346, plague broke out among the besiegers and from them penetrated into the town. When spring arrived, the Italians fled on their ships. And the Black Death slipped unnoticed on board and sailed with them.

***

The extent of the contagious power of the Black Death has been almost mystifying. The central explanation lies within characteristic features of medieval society in a dynamic phase of modernisation heralding the transformation from a medieval to early modern European society. Early industrial market-economic and capitalistic developments had advanced more than is often assumed, especially in northern Italy and Flanders. New, larger types of ship carried great quantities of goods over extensive trade networks that linked Venice and Genoa with Constantinople and the Crimea, Alexandria and Tunis, London and Bruges. In London and Bruges the Italian trading system was linked to the busy shipping lines of the German Hanseatic League in the Nordic countries and the Baltic area, with large broad-bellied ships called cogs. This system for long-distance trade was supplemented by a web of lively short and medium-distance trade that bound together populations all over the Old World.

The strong increase in population in Europe in the High Middle Ages (1050-1300) meant that the prevailing agricultural technology was inadequate for further expansion. To accommodate the growth, forests were cleared and mountain villages settled wherever it was possible for people to eke out a living. People had to opt for a more one-sided husbandry, particularly in animals, to create a surplus that could be traded for staples such as salt and iron, grain or flour. These settlements operated within a busy trading network running from coasts to mountain villages. And with tradesmen and goods, contagious diseases reached even the most remote and isolated hamlets.

In this early phase of modernisation, Europe was also on the way to ‘the golden age of bacteria’, when there was a great increase in epidemic diseases caused by increases in population density and in trade and transport while knowledge of the nature of epidemics, and therefore the ability to organise efficient countermeasures to them, was still minimal. Most people believed plague and mass illness to be a punishment from God for their sins. They responded with religious penitential acts aimed at tempering the Lord’s wrath, or with passivity and fatalism: it was a sin to try to avoid God’s will.

Much new can be said on the Black Death’s patterns of territorial spread. Of particular importance was the sudden appearance of the plague over vast distances, due to its rapid transportation by ship. Ships travelled at an average speed of around 40km a day which today seems quite slow. However, this speed meant that the Black Death easily moved 600km in a fortnight by ship: spreading, in contemporary terms, with astonishing speed and unpredictability. By land, the average spread was much slower: up to 2km per day along the busiest highways or roads and about 0.6km per day along secondary lines of communication.

As already noted, the pace of spread slowed strongly during the winter and stopped completely in mountain areas such as the Alps and the northerly parts of Europe. Yet, the Black Death often rapidly established two or more fronts and conquered countries by advancing from various quarters.

Inspired by the Black Death, The Dance of Death or Danse Macabre, an allegory on the universality of death, is a common painting motif in the late medieval period.Italian ships from Kaffa arrived in Constantinople in May 1347 with the Black Death on board. The epidemic broke loose in early July. In North Africa and the Middle East, it started around September 1st, having arrived in Alexandria with ship transport from Constantinople. Its spread from Constantinople to European Mediterranean commercial hubs also started in the autumn of 1347. It reached Marseilles by about the second week of September, probably with a ship from the city. Then the Italian merchants appear to have left Constantinople several months later and arrived in their home towns of Genoa and Venice with plague on board, some time in November. On their way home, ships from Genoa also contaminated Florence’s seaport city of Pisa. The spread out of Pisa is characterized by a number of metastatic leaps. These great commercial cities also functioned as bridgeheads from where the disease conquered Europe.

In Mediterranean Europe, Marseilles functioned as the first great centre of spread. The relatively rapid advance both northwards up the Rhône valley to Lyons and south-westwards along the coasts towards Spain – in chilly months with relatively little shipping activity – is striking. As early as March 1348, both Lyon’s and Spain’s Mediterranean coasts were under attack.

En route to Spain, the Black Death also struck out from the city of Narbonne north-westwards along the main road to the commercial centre of Bordeaux on the Atlantic coast, which by the end of March had become a critical new centre of spread. Around April 20th, a ship from Bordeaux must have arrived in La Coruña in northwestern Spain; a couple of weeks later another ship from there let loose the plague in Navarre in northeastern Spain. Thus, two northern plague fronts were opened less than two months after the disease had invaded southern Spain.

Another plague ship sailed from Bordeaux, northwards to Rouen in Normandy where it arrived at the end of April. There, in June, a further plague front moved westwards towards Brittany, south-eastwards towards Paris and northwards in the direction of the Low Countries.

Yet another ship bearing plague left Bordeaux a few weeks later and arrived around May 8th, in the southern English town of Melcombe Regis, part of present-day Weymouth in Dorset: the epidemic broke out shortly before June 24th. The significance of ships in the rapid transmission of contagion is underscored by the fact that at the time the Black Death landed in Weymouth it was still in an early phase in Italy. From Weymouth, the Black Death spread not only inland, but also in new metastatic leaps by ships, which in some cases must have travelled earlier than the recognized outbreaks of the epidemic: Bristol was contaminated in June, as were the coastal towns of the Pale in Ireland; London was contaminated in early August since the epidemic outbreak drew comment at the end of September. Commercial seaport towns like Colchester and Harwich must have been contaminated at about the same time. From these the Black Death spread inland. It is now also clear that the whole of England was conquered in the course of 1349 because, in the late autumn of 1348, ship transport opened a northern front in England for the Black Death, apparently in Grimsby.

***

The early arrival of the Black Death in England and the rapid spread to its southeastern regions shaped much of the pattern of spread in Northern Europe. The plague must have arrived in Oslo in the autumn of 1348, and must have come with a ship from south-eastern England, which had lively commercial contacts with Norway. The outbreak of the Black Death in Norway took place before the disease had managed to penetrate southern Germany, again illustrating the great importance of transportation by ship and the relative slowness of spread by land. The outbreak in Oslo was soon stopped by the advent of winter weather, but it broke out again in the early spring. Soon it spread out of Oslo along the main roads inland and on both sides of the Oslofjord. Another independent introduction of contagion occurred in early July 1349 in the town of Bergen; it arrived in a ship from England, probably from King’s Lynn. The opening of the second plague front was the reason that all Norway could be conquered in the course of 1349. It disappeared completely with the advent of winter, the last victims died at the turn of the year.

The early dissemination of the Black Death to Oslo, which prepared the ground for a full outbreak in early spring, had great significance for the pace and pattern of the Black Death’s further conquest of Northern Europe. Again ship transport played a crucial role, this time primarily by Hanseatic ships fleeing homewards from their trading station in Oslo with goods acquired during the winter. On their way the seaport of Halmstad close to the Sound was apparently contaminated in early July. This was the starting point for the plague’s conquest of Denmark and Sweden, which was followed by several other independent introductions of plague contagion later; by the end of 1350 most of these territories had been ravaged.

However, the voyage homewards to the Hanseatic cities on the Baltic Sea had started significantly earlier. The outbreak of the Black Death in the Prussian town of Elbing (today the Polish town of Elblag) on August 24th, 1349, was a new milestone in the history of the Black Death. A ship that left Oslo at the beginning of June would probably sail through the Sound around June 20th and reach Elbing in the second half of July, in time to unleash an epidemic outbreak around August 24th. Other ships that returned at the end of the shipping season in the autumn from the trading stations in Oslo or Bergen, brought the Black Death to a number of other Hanseatic cities both on the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. The advent of winter stopped the outbreaks initially as had happened elsewhere, but contagion was spread with goods to commercial towns and cities deep into northern Germany. In the spring of 1350, a northern German plague front was formed that spread southwards and met the plague front which in the summer of 1349 had formed in southern Germany with importation of contagion from Austria and Switzerland.

***

Napoleon did not succeed in conquering Russia. Hitler did not succeed. But the Black Death did. It entered the territory of the city state of Novgorod in the late autumn of 1351 and reached the town of Pskov just before the winter set in and temporarily suppressed the epidemic; thus the full outbreak did not start until the early spring of 1352. In Novgorod itself, the Black Death broke out in mid-August. In 1353, Moscow was ravaged, and the disease also reached the border with the Golden Horde, this time from the west, where it petered out. Poland was invaded by epidemic forces coming both from Elbing and from the northern German plague front and, apparently, from the south by contagion coming across the border from Slovakia via Hungary.

Iceland and Finland are the only regions that, we know with certainty, avoided the Black Death because they had tiny populations with minimal contact abroad. It seems unlikely that any other region was so lucky.

How many people were affected? Knowledge of general mortality is crucial to all discussions of the social and historical impact of the plague. Studies of mortality among ordinary populations are far more useful, therefore, than studies of special social groups, whether monastic communities, parish priests or social elites. Because around 90 per cent of Europe’s population lived in the countryside, rural studies of mortality are much more important than urban ones.

Researchers generally used to agree that the Black Death swept away 20-30 per cent of Europe’s population. However, up to 1960 there were only a few studies of mortality among ordinary people, so the basis for this assessment was weak. From 1960, a great number of mortality studies from various parts of Europe were published. These have been collated and it is now clear that the earlier estimates of mortality need to be doubled. No suitable sources for the study of mortality have been found in the Muslim countries that were ravaged.

The mortality data available reflects the special nature of medieval registrations of populations. In a couple of cases, the sources are real censuses recording all members of the population, including women and children. However, most of the sources are tax registers and manorial registers recording households in the form of the names of the householders. Some registers aimed at recording all households, also the poor and destitute classes who did not pay taxes or rents, but the majority recorded only householders who paid tax to the town or land rent to the lord of the manor. This means that they overwhelmingly registered the better-off adult men of the population, who for reasons of age, gender and economic status had lower mortality rates in plague epidemics than the general population. According to the extant complete registers of all households, the rent or tax-paying classes constituted about half the population both in the towns and in the countryside, the other half were too poor. Registers that yield information on both halves of the populations indicate that mortality among the poor was 5-6 per cent higher. This means that in the majority of cases when registers only record the better-off half of the adult male population, mortality among the adult male population as a whole can be deduced by adding 2.5-3 per cent.

Another fact to consider is that in households where the householder survived, other members often died. For various reasons women and children suffer higher incidence of mortality from plague than adult men. A couple of censuses produced by city states in Tuscany in order to establish the need for grain or salt are still extant. They show that the households were, on average, reduced in the countryside from 4.5 to 4 persons and in urban centres from 4 to 3.5 persons. All medieval sources that permit the study of the size and composition of households among the ordinary population produce similar data, from Italy in southern Europe to England in the west and Norway in northern Europe. This means that the mortality among the registered households as a whole was 11-12.5 per cent higher than among the registered householders.

Detailed study of the mortality data available points to two conspicuous features in relation to the mortality caused by the Black Death: namely the extreme level of mortality caused by the Black Death, and the remarkable similarity or consistency of the level of mortality, from Spain in southern Europe to England in north-western Europe. The data is sufficiently widespread and numerous to make it likely that the Black Death swept away around 60 per cent of Europe’s population. It is generally assumed that the size of Europe’s population at the time was around 80 million. This implies that that around 50 million people died in the Black Death. This is a truly mind-boggling statistic. It overshadows the horrors of the Second World War, and is twice the number murdered by Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union. As a proportion of the population that lost their lives, the Black Death caused unrivalled mortality.

This dramatic fall in Europe’s population became a lasting and characteristic feature of late medieval society, as subsequent plague epidemics swept away all tendencies of population growth. Inevitably it had an enormous impact on European society and greatly affected the dynamics of change and development from the medieval to Early Modern period. A historical turning point, as well as a vast human tragedy, the Black Death of 1346-53 is unparalleled in human history.

Ole J. Benedictow is Emeritus Professor of History at the Universtiy of Oslo, Norway.

Further Reading:

The Black Death, 1346-1353. The Complete History (Boydell & Brewer, 2004)

Ole J. Benedictow, ‘Plague in the Late Medieval Nordic Countries’, Epidemiological Studies (1996)

M.W. Dols,The Black Death in the Middle East (Princeton, 1970)

J. Hatcher,Plague, Population and the English Economy 1348-1530 (Basingstoke, 1977)

J. Hatcher ‘England in the Aftermath of the Black Death’ (Past & Present, 1994)

L.F. Hirst, The Conquest of Plague (Oxford, 1953).

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=BLACK+DEATH+

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=BLACK+DEATH+