More than 3,000 voyages engaged in the trade in enslaved Africans left from London, responsible for transporting at least 800,000 into slavery

Many in the city made their fortunes off the back of slavery and colonial oppression, a fact that is only now being partially acknowledged

Bloomberg Published: 24 Jun, 2020

A statue of a City of London dragon stands on a street lamp outside the Royal Exchange in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

If there’s one thing that foretold the City of London’s ambition to become the epicentre of finance it was the founding of the Royal Exchange almost 500 years ago.

The driving force behind the capital’s first purpose-built centre for trading stocks was Sir Thomas Gresham, whose legacy survives in the college, City street and law of economics that bear his name.

Black Lives Matter: for Koreans, an uncomfortable reminder that racism is legal

11 Jun 2020

Less celebrated is the role of his prominent backer in the venture, Sir William Garrard: former Lord Mayor and pioneer of English involvement in the slave trade.

The City of London is interwoven with so many layers of history, from Roman to medieval, the civil war and the age of empire, that the lives of the myriad figures who contributed to its status today are often obscured by time.

A sign for the street named after Sir Thomas Gresham sits on a building in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

But with outside scrutiny comes the realisation that many made their fortunes off the back of slavery and colonial oppression, a fact that is now being acknowledged by some of the financial district’s most venerable names, shaking the foundations upon which many of these institutions were built.

The Bank of England apologised last week for “some inexcusable connections” to slavery by former governors. Barclays is examining its own history. While “we can’t change what’s gone before us,” the bank is committed to “do more to further foster our culture of inclusiveness, equality and diversity.”

A statue of a City of London dragon stands on a street lamp outside the Royal Exchange in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

If there’s one thing that foretold the City of London’s ambition to become the epicentre of finance it was the founding of the Royal Exchange almost 500 years ago.

The driving force behind the capital’s first purpose-built centre for trading stocks was Sir Thomas Gresham, whose legacy survives in the college, City street and law of economics that bear his name.

Black Lives Matter: for Koreans, an uncomfortable reminder that racism is legal

11 Jun 2020

Less celebrated is the role of his prominent backer in the venture, Sir William Garrard: former Lord Mayor and pioneer of English involvement in the slave trade.

The City of London is interwoven with so many layers of history, from Roman to medieval, the civil war and the age of empire, that the lives of the myriad figures who contributed to its status today are often obscured by time.

A sign for the street named after Sir Thomas Gresham sits on a building in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

But with outside scrutiny comes the realisation that many made their fortunes off the back of slavery and colonial oppression, a fact that is now being acknowledged by some of the financial district’s most venerable names, shaking the foundations upon which many of these institutions were built.

The Bank of England apologised last week for “some inexcusable connections” to slavery by former governors. Barclays is examining its own history. While “we can’t change what’s gone before us,” the bank is committed to “do more to further foster our culture of inclusiveness, equality and diversity.”

“We understand that we cannot always be proud of our past,” Lloyd’s of London, which began life insuring ships and their cargo in the late 17th century, said in a statement. “In particular, we are sorry for the role played by the Lloyd’s market in the 18th and 19th century slave trade – an appalling and shameful period of English history, as well as our own.”

Those cases were far from isolated.

This was big business, and the rich men of the City were in the thick of itRichard Drayton, history professor

According to Richard Drayton, professor of imperial history at King’s College London,

Britain became the principal slaving nation of the modern world, with the City providing the finance to facilitate trade with the plantation colonies. “This was big business, and the rich men of the City were in the thick of it,” Drayton said in a lecture delivered in the Museum of London last October.

The “triangle trade” involved shipping manufactured goods to western Africa and exchanging them for human beings, who were transported in appalling conditions to the Caribbean and sold as slaves to work in the plantations.

The tobacco, rum and most of all the sugar that were the fruits of their forced labour were then taken back to Europe. “The formation of the City of London was shaped significantly by sugar,” said Nick Draper, one of the lead researchers on University College London’s groundbreaking Legacies of British Slave Ownership project. “Merchants in London would advance credit to planters and guarantee remittances to slave traders so that London merchant houses became the centre of this economic system built on Caribbean slavery.”

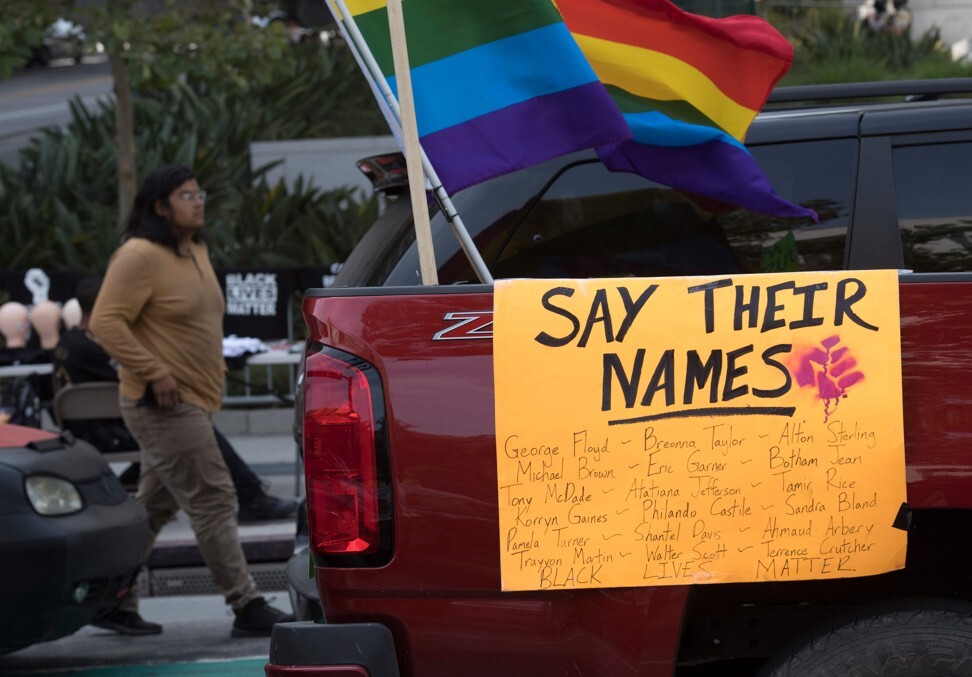

That uncomfortable, probing questions are now being asked of the institutions that profited from the trade is down to the Black Lives Matter movement that began in the

US and crossed the Atlantic, prompting a re-examining of the role of prominent figures with sometimes contradictory histories in London but also in the mercantile cities of Liverpool, Bristol and Glasgow.

A protester holds a US flag during a Black Lives Matter protest in front of New York City Hall. Photo: DPA

Those cases were far from isolated.

This was big business, and the rich men of the City were in the thick of itRichard Drayton, history professor

According to Richard Drayton, professor of imperial history at King’s College London,

Britain became the principal slaving nation of the modern world, with the City providing the finance to facilitate trade with the plantation colonies. “This was big business, and the rich men of the City were in the thick of it,” Drayton said in a lecture delivered in the Museum of London last October.

The “triangle trade” involved shipping manufactured goods to western Africa and exchanging them for human beings, who were transported in appalling conditions to the Caribbean and sold as slaves to work in the plantations.

The tobacco, rum and most of all the sugar that were the fruits of their forced labour were then taken back to Europe. “The formation of the City of London was shaped significantly by sugar,” said Nick Draper, one of the lead researchers on University College London’s groundbreaking Legacies of British Slave Ownership project. “Merchants in London would advance credit to planters and guarantee remittances to slave traders so that London merchant houses became the centre of this economic system built on Caribbean slavery.”

That uncomfortable, probing questions are now being asked of the institutions that profited from the trade is down to the Black Lives Matter movement that began in the

US and crossed the Atlantic, prompting a re-examining of the role of prominent figures with sometimes contradictory histories in London but also in the mercantile cities of Liverpool, Bristol and Glasgow.

A protester holds a US flag during a Black Lives Matter protest in front of New York City Hall. Photo: DPA

More than 3,000 voyages of ships engaged in the trade in enslaved Africans left from London, responsible for transporting at least 800,000 people into slavery in the Americas, according to Diana Paton, a history professor at the University of Edinburgh. “The slavery economy ran on credit, an important proportion of which was extended by London-based individuals and firms,” she said.

Walk through the warren of ancient streets lined with discrete Victorian facades and modern steel-and-glass towers that make up London’s Square Mile – effectively a city within a city – and it’s possible to find echoes of that legacy.

Pubs with names like the Jamaica Wine House in St Michael’s Alley, or the Sugar Loaf on Cannon Street – while both housed in 19th century buildings constructed after the abolition of slavery – hint at what came before.

Whereas in the Elizabethan age, financiers like Garrard invested in the voyages of glorified privateers, by the 17th century the trade was more developed, if no less barbaric.

A section of the ‘Gilt of Cain’ monument commemorating the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade stands in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

Barbados became England’s first sugar producing colony in the 1640s, followed by Jamaica after it was seized from Spain. Cargoes of cane were landed at the sugar wharf beside the Tower of London at what is now Customs House. Cannon Street was the site of sugar refineries that helped fuel the rise of England, and after the union of 1707, Great Britain, to a world power.

In 1672 came the founding of the Royal African Company, an enterprise backed by the monarchy that historian William Pettigrew has said “shipped more enslaved African women, men and children to the Americas than any other single institution” during the transatlantic slave trade.

Walk through the warren of ancient streets lined with discrete Victorian facades and modern steel-and-glass towers that make up London’s Square Mile – effectively a city within a city – and it’s possible to find echoes of that legacy.

Pubs with names like the Jamaica Wine House in St Michael’s Alley, or the Sugar Loaf on Cannon Street – while both housed in 19th century buildings constructed after the abolition of slavery – hint at what came before.

Whereas in the Elizabethan age, financiers like Garrard invested in the voyages of glorified privateers, by the 17th century the trade was more developed, if no less barbaric.

A section of the ‘Gilt of Cain’ monument commemorating the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade stands in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

Barbados became England’s first sugar producing colony in the 1640s, followed by Jamaica after it was seized from Spain. Cargoes of cane were landed at the sugar wharf beside the Tower of London at what is now Customs House. Cannon Street was the site of sugar refineries that helped fuel the rise of England, and after the union of 1707, Great Britain, to a world power.

In 1672 came the founding of the Royal African Company, an enterprise backed by the monarchy that historian William Pettigrew has said “shipped more enslaved African women, men and children to the Americas than any other single institution” during the transatlantic slave trade.

Its shareholders included 15 lord mayors and 38 City of London council members known as ldermen, according to Drayton. Edward Colston, whose statue was torn down and dumped in Bristol harbour this month, was a deputy governor. Its symbol – as stamped on guineas of the day made with African gold – was an elephant with a riding carriage, or houdah: the Elephant and Castle.

It’s not known if the symbol bears any relation to the London landmark of the same name, such are the layers of juxtaposed history. Take the Lloyd’s building: Located off Leadenhall, it occupies the site of the headquarters of the former East India Company, which employed a private army to appropriate the subcontinent’s wealth. The East India Company’s original marble fireplace was incorporated into the Foreign Office in Whitehall when it opened in 1868.

Pedestrians pass a section of the Lloyd's of London building in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

Some evidence of past complicity is barely concealed. In the basement of the Bank of England are the papers of one former governor, Humphry Morice, who was the largest slave trader of his day in the 1720s, according to Anne Ruderman, an assistant professor of economic history at the London School of Economics, who is writing a book on the transatlantic slave trade. “You can see the instructions that Morice wrote to his captains before sending them on slave voyages,” she said by email. “You can see detailed daily trading logs of how many enslaved people his captains purchased and at what prices.”

Still, the Guildhall off Moorgate, the ceremonial and administrative centre of the City since the 15th century, illustrates the difficulty in unpicking and assigning guilt to institutions. Inside is a statue of William Beckford, a two-times lord mayor and owner of thousands of acres of Jamaican plantations worked by slaves. The Guildhall was also the scene of a court case over the killing of more than 100 slaves at sea that spurred the anti-slavery movement, leading to full abolition in 1833.

Even then, Drayton said, slavery continued for decades in other countries in the Americas. “London was the close partner of the expansion of the cotton south in the United States, creating complex mortgage-backed securities which provided a paper veil for a new kind of slave-ownership,” he said.

David Barclay, one of the founders of the eponymous bank, was a “keen and committed advocate for abolition of the slave trade,” even as his bank then in Lombard Street financed plantation mortgages, causing him to suffer a “moral dilemma,” according to the UCL slave ownership project.

A sign hangs above an entrance to a branch of Barclays bank in the City of London. Photo: Bloomberg

The City’s institutions are now confronted with their own moral dilemma. Lloyd’s is among those to have pledged to invest in programmes to attract and develop black and minority ethnic talent. In 2018, 28 per cent of the City’s workforce was of non-white origin. The City of London Corporation, the financial district’s governing body, said it understands “it’s not enough to say that we are against racism but we have to work to eradicate racism in all that we do”.

Sajid Javid, the former chancellor of the exchequer, has spoken about his decision to leave the City for New York early in his career in part because of his ethnicity and class. “The UK has come a long way since then,” he told PBS. “But we still need to make sure we’re not complacent and we keep tackling racial injustice wherever we find it.”

Kehinde Andrews, a professor of black studies at Birmingham City University, says the wealth generated then is still with us now, helping to perpetuate the racial divide. “It’s not past, it’s very much the present and a continuation, and the banks are one of the key drivers,” he said. “The idea they can just apologise and have some more diversity is frankly insulting.”

It’s really hard to separate slavery from so many things that we know of in modern Britain Dominic Burris-North, tour guide

Dominic Burris-North is one of just two qualified “Blue Badge” guides who provide tours of the City focusing on its historic ties to the slave trade. The reactions, he says, are predominantly shock, horror and dismay. Burris-North has a personal connection to the dilemmas raised: he is the son of a father whose own parents came from Jamaica as part of the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants invited to the UK after World War II.

“It’s really hard to separate slavery from so many things that we know of in modern Britain, from the royal family to our galleries to the British Museum to the Bank of England to former prime ministers – all of these names, all of these institutions,” he said. “As more people start to understand and hear about these things, eventually there will be a reckoning.”