Victoria Rossi, El Paso Matters

Mon, November 29, 2021,

When Lori Edwards told her transgender teenage daughter that Texas’ House Bill 25 had passed, the 14-year-old turned away and started flipping through her phone.

“Oh that sucks,” Emily said, and went silent.

During the regular Texas legislative session this spring, a rash of anti-trans bills filed by Republican state lawmakers had sent Emily’s mental health, along with her grades, spiraling downward. What was the point of studying, reasoned Emily, who was assigned male at birth but identifies as a girl, if they would just have to leave El Paso for a different state?

When Texas’ regular legislative session ended in late May without any anti-trans measures becoming law, the Edwards family breathed a sigh of relief. But then in July, Gov. Greg Abbott called a special session.

Then another, and another. And with each special session, Abbott pushed lawmakers to ban transgender kids from playing on sports teams that fit their gender identity. HB 25 was Texas Republicans’ fourth attempt to enact the ban this year. At home, Edwards turned off the news.

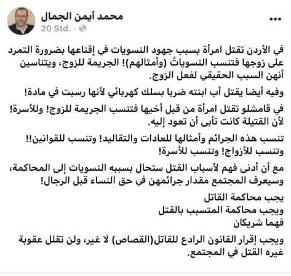

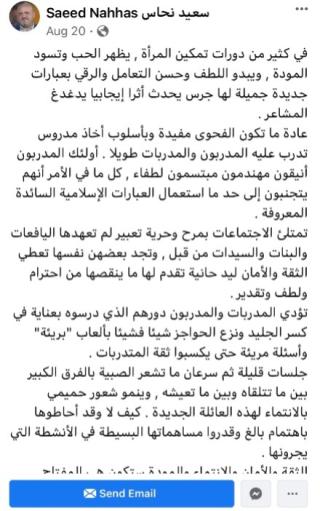

Emily Edwards, right, and her brother Emilio played soccer when they were younger, but both have felt pushed away from sports. They are shown with their father, Tyler. (Photo courtesy of the Edwards family)

On Oct. 15, two months into Emily’s first semester at Coronado High School, HB 25 cleared its final legislative hurdle in the Texas statehouse. It was signed by the governor Monday.

“Did you hear what I said?” Edwards asked her daughter. “It passed.”

Emily hid her face behind her hair, a telltale sign she did not want to talk. “What difference does it make, Mom. I’m not going to be able to do any of that stuff anyway.”

The Edwards are not a sports family, but they used to be. Growing up, Edwards competed in volleyball and cross country; she studied kinesiology in high school and for a brief period majored in sports medicine. “I loved being around the football players and helping and being a trainer,” Edwards said.

Emily was in a youth running club, took karate and played soccer.

But well before lawmakers took aim at trans student athletes, years of discrimination and bullying based on Emily’s growing sense of her gender identity led Edwards to pull her daughter from sports.

“My child doesn’t play sports (anymore) because it was never given as an option,” Edwards said. “It wasn’t given as an option because we had to protect her.”

Five years earlier, from the sidelines of a youth soccer game, other parents would heckle her child right in front of her. “Why is that little boy like a little girl?” they would say in Spanish, thinking that she couldn’t understand. “He’s just being sissy. He can’t even kick very hard.” And why, they wondered, was the boy’s hair so long?

Edwards said nothing, comforted by the fact that the comments never reached Emily — who loved soccer, and loved having long, gleaming blond hair. It was one of the few ways that Emily, who then presented as a boy and used “he” pronouns, could outwardly express what he’d soon come to realize was his true gender identity.

At 8 years old, Emily had begun to say: maybe I could be a girl someday.

Soon, however, the insults of the parents reached their children. At Emily’s elementary school in Phoenix, kids taunted with “you suck at being a boy,” and wouldn’t let Emily into the boys’ bathroom.

Emily Edwards participated in Kids Excel El Paso, an extracurricular program that uses dance to teach children determination, discipline and excellence. (Photo courtesy of the Edwards family)

The family left Phoenix for El Paso. There, in gym class, another sport gave Emily a word for the question that had been around for years. The 9-year-old came home from school to say the boys in PE football wouldn’t let Emily play football with them, saying, “This is for boys only. No transgenders.”

Emily asked her mother what the word meant.

Edwards pulled up a series of YouTube videos from transgender girls in their teens who explained the term’s meaning — someone whose gender identity is different from the sex they were assigned at birth — and how they’d felt growing up in boys’ bodies, knowing they were girls.

“Oh,” Emily said. “That’s me.”

“I hate that the first time she heard that word, it was an insult,” Edwards said. “As if it’s a bad thing.”

As soon as Emily had that word, Edwards saw her daughter become a new person. When someone told her she sucked at being a boy, she’d respond, “Well obviously. I’m transgender. I’m a girl. Thanks for noticing.”

Like many parents, Edwards has agonized over past parenting choices. And while she’d been determined to let Emily arrive at her gender identity at her own time, on her own terms, she now believes she should have given her daughter the vocabulary sooner; maybe knowing the word “transgender” could have avoided some suffering.

Edwards is sometimes struck with guilt for the decision that she and her husband came to about sports. The last day of fifth grade was the last time Emily went to school dressed as a boy. From that time on, “we very, very, very much discouraged sports,” Edwards said.

She and her husband worried about the uniforms; they worried about the locker rooms.

“It’s a fine line between being able to pursue things that are extracurricular, like volleyball or track or soccer, and continually outing herself every single time and having to fight for every single thing. Like it doesn’t necessarily prove to be worth it at that point.”

More than anything, they worried about the other kids’ parents.

“Parents can be crazy as it is already, when it comes to sports,” Edwards said. “Just in general, you go and you’re like, ‘wow, this person is gonna have an aneurysm right here next to me,’ because they’re just so pumped, right? But when you throw the added context of their child also competing against someone who’s transgender, and then throw in the fear mongering. … These parents can be absolutely vile and abusive.”

Family football-watching nights became rare. Emily’s younger brother joined band and “now has this opinion that all athletes are jerks,” Edwards said. “It makes me so sad that he thinks that, but he definitely formed that opinion by watching them bully his sister.”

Emily didn’t push back.

“The love that she had for sports was clouded and very much destroyed by that machismo thing,” her mother said.

And at that age, Emily trusted her parents’ choices. “Whether or not sports would have been a big part of her life, we’ll never know. Because I took it,” Edwards said. “I had to.”

Emily Edwards wore a dress in public for the first time in 2018, when she saw a performance of “The Lion King” at the Plaza Theatre. (Photo courtesy of the Edwards family)

Emily has stayed active through dance, and has found other interests “that absolutely enrich her life,” Edwards said, like choir and gaming and theater and anime. She volunteers at the Borderland Rainbow Center, the LGBTQ+ rights nonprofit where her mother works, and is studying to be a veterinarian.

“We really pushed her wholeheartedly into things that were co-ed where it wouldn’t be made such a big issue. … But the fact that she doesn’t have sports as an option breaks my heart.”

As a mother, Edwards has tried to look at least five, 10 years ahead. Planning the family’s move to El Paso while Emily was still in elementary school, Edwards chose their new neighborhood based on what middle and high schools it would feed into. She wasn’t looking for the best schools, necessarily. She was looking for schools that would keep Emily safe — and found them, she said, in Hornedo Middle School and Coronado High School.

But even as Edwards tried to predict the future, she never imagined that the social issues they’d encountered in sports would draw the attention of state legislators.

“I really just thought it was going to be a social issue,” Edwards said. “I never thought there would be bills that would be passed that would give these people fuel for their social issues. That’s the difference, right. When they have legal backing, that gives them power — more power than they need, is what I’m saying — to discriminate, and to put her safety at risk.”

Both mother and daughter spent much of last spring fighting against the onslaught of Texas bills that targeted trans youth, triple the number introduced by any other state. Trans children and their families flocked from across Texas, including El Paso, to deliver passionate testimonies against the bill.

But as the fight continued into the summer, Emily grew wary. Adri Perez, an ACLU policy and advocacy strategist who lobbies against bills targeting Texas’ LGBTQ+ community, saw the same effect play out with the kids who came to the Capitol.

“They get up there and talk into a podium and a microphone that’s taller than they are,” Perez said. “It’s heartbreaking to see, to know that these kids’ spirits are effectively being broken every time these hearings come up.”

Edwards still doesn’t know what to make of Emily’s seemingly calm reaction to the new law. Maybe the reaction she’d expected from Emily was something closer to her own: “This bill passing here in Texas has absolutely devastated my ability to believe that we can affect change,” she said. She worries that the sports ban is just the beginning.

Edwards hoped that, after months of bracing herself for the worst, Emily really was OK. But the other day, in the drive-thru line at Dutch Bros, a construction cone blocked their way and Emily exploded.

“Everybody wants to tell you what you can do,” Emily said, far angrier than Edwards would have expected. “Now they tell you that you can’t play sports, you can’t get married, you can’t have kids — now you can’t even drive your car.”

It was Emily’s way, her mother said, of “communicating something that hurts so much.”

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Related: Sign up for The 74’s newsletter

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/XKKA3OMECSS5PHWUYU4ISNZBBY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/3TSHDXBBYDJ3X44XWH4MZ54HEQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MBYECHLNVW2WIYFKQQBZXEADJM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/BYU7V6PLEMGX2EZ7QBP7MOUGOI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/XNZPZQAM5IG2Z5O4PLUHKLBVBM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/6YAV5KZDEZUPROEAJ22IHMPRGU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MPBIOI73KBCDAA3POZH3F2HLAY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/HIXAYI2EFSHYVH72QPRSHD6VD4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/FYBK6YTDJIBBOPHETVMU3JY7FE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PJC6SFNUW5SUJODAGAXIAQSBVA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/RDHMZUD5D3AXJRPIGPIPMXVZKY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/VMGSTWZ6IOQ3OUBSBEL7OQTY24.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MTP2ZWQF67YCSLBXEGNWKUKMSU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/3AK7Y2U24MFXRPX22NMKTXWHVU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DZ6H4DSSPVJVPBYPWNWZFKQUM4.jpg)