'Employees will just say no': Bosses pushing staff back to the office could be fighting a losing battle

Staff are used to remote work, have different expectations about work-life balance and are now factoring in cost of inflation

Financial Times

Anjli Raval in London and Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson in New York

Publishing date: Sep 06, 2022

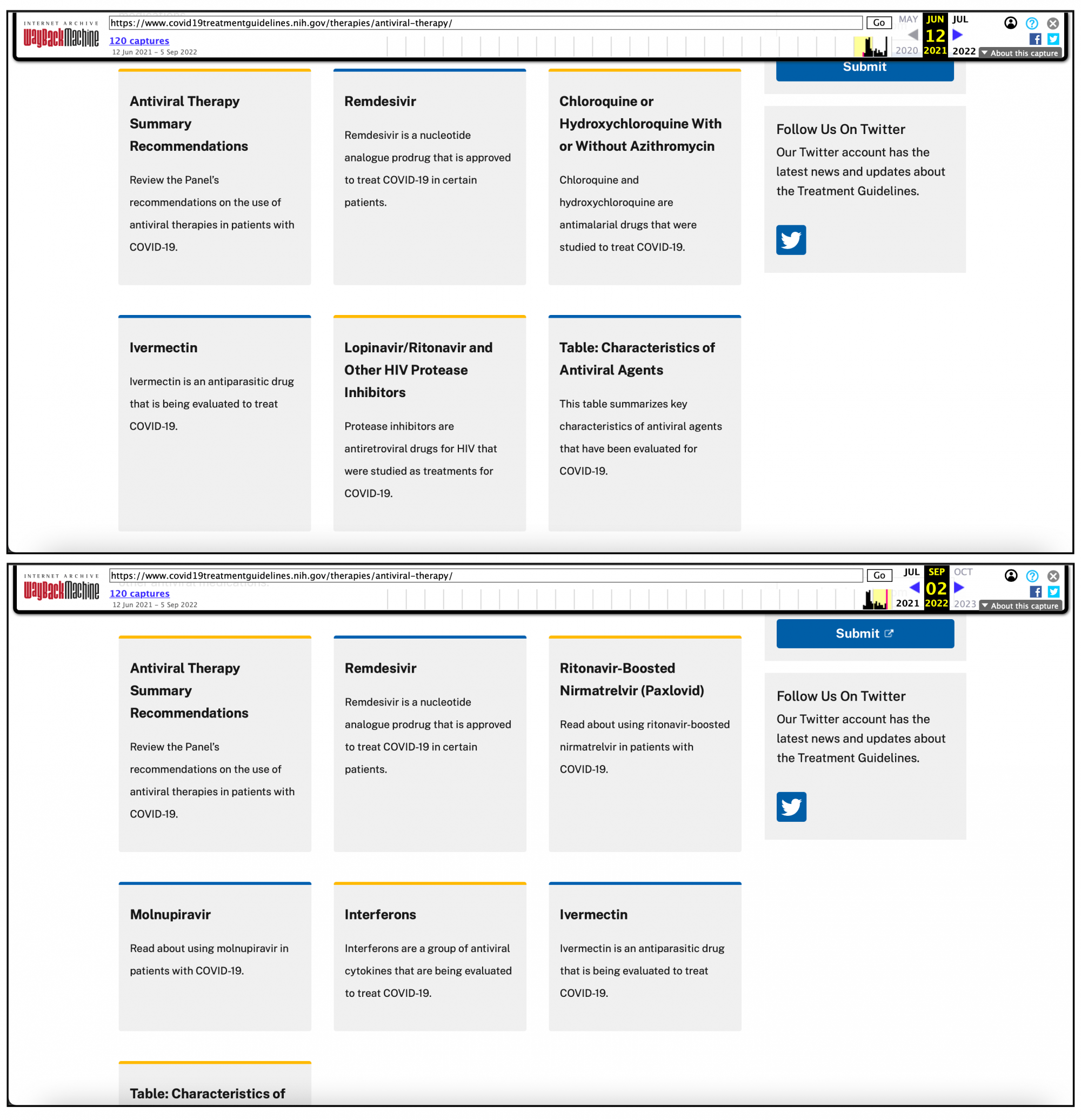

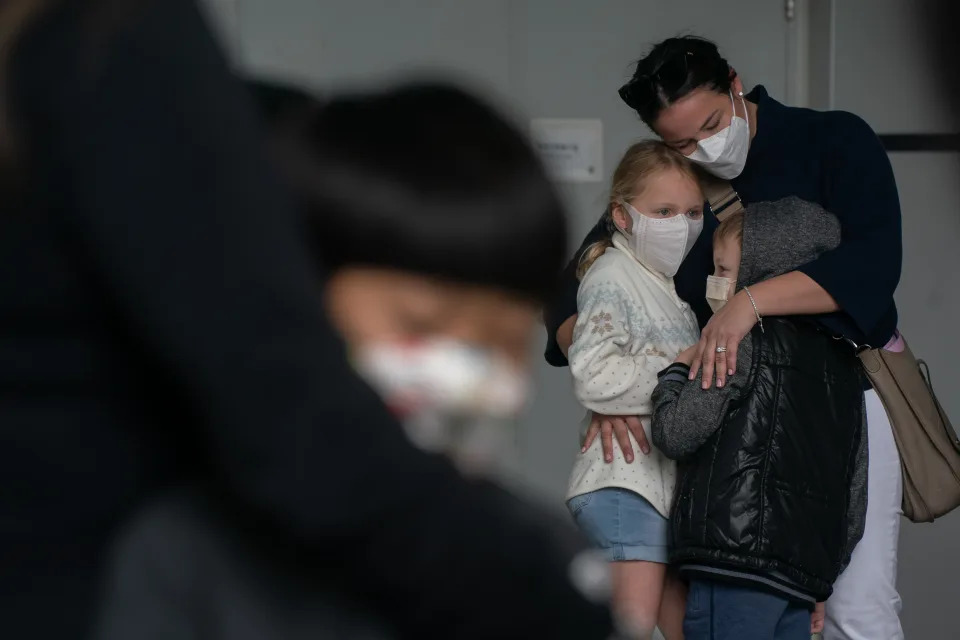

Commuters in Toronto's financial district in November.

PHOTO BY COLE BURSTON/BLOOMBERG

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. boss David Solomon has long been a critic of remote work, describing the pandemic-related shift once as “an aberration.” This week he called time on the practice, scrapping most of the bank’s remaining COVID-19 restrictions for United States employees in a bid to get as many as possible back into the office.

For more than two years companies around the world embraced remote work and hybrid home-office arrangements as infections surged and the death toll escalated.

But as summer comes to an end in North America and Europe, some of the biggest companies are making a concerted push to get people to return to the office. They range from electric carmaker Tesla Inc., whose boss Elon Musk has demanded employees to be back at their desks 40 hours a week, to tech giant Apple Inc. and fitness company Peloton Interactive Inc., which are both pushing for at least three days a week.

It is not the first time big business has tried to reverse the shift to working from home. In the autumn of 2021, and even 2020, companies developed plans to initiate a broad comeback to eerie office buildings, only for new waves of infections to leave managers wary of butting heads with staff at an intensely fragile time.

This year is different, however. With people generally less fearful of virus spread, many bosses believe conditions are now as close as they are likely to get to pre-pandemic times. With Labour Day behind us and school terms starting across Europe, some executives are getting impatient and are taking a harder line.

Goldman Sachs chief executive David Solomon.

PHOTO BY SIMON DAWSON/BLOOMBERG

According to one executive headhunter, business leaders are experiencing “do-gooder fatigue” — in reaction, in part, to the greater focus on employee wellbeing during the pandemic. “The feeling is, we need to get back to business.”

This could, however, lead to confrontations with staff who have grown used to remote working, have different expectations about work-life balance and are now weighing up the costs of going back to the office as inflation surges.

“People want to come into big cities to socialize, see friends and go to cultural events. But, for work, many people will say they can do it better at home,” says Ann Francke, chief executive of the Chartered Management Institute, a professional body in the U.K. “The pandemic forced people to ask…’Do we really need to organize work in this way?'” she adds. “This irks CEOs.”

That makes the coming weeks a critical moment for the future of the office — but also for all the industries that revolve around office workers, from the commercial property sector to sandwich shops and gyms.

If they're forcing us to commute, shouldn't they offset costs for us?

“Hybrid work is here to stay,” Enrique Lores, chief executive of HP, which sells printers and laptops, said last week. The expected recovery in the company’s commercial revenues had been hit by the slower-than-expected return to workplaces and it now expects the office printer market to recover to only 80 per cent of its pre-pandemic size.

“I don’t know any company that has decided, or convinced their employees, that they need to be back in the office five days per week, every week of the month.”

For some employees — especially the less well paid — the pressure to return is also now wrapped up in the cost-of-living issues that many are grappling with, from higher energy bills if they stay at home to the expense of travelling to and from the office and child care.

The conundrum for workers was laid bare on Blind, the anonymous professional network. “If they’re forcing us to commute, shouldn’t they offset costs for us?” wrote one person posting about their company’s return-to-work policy. A second questioned the legality of mandates to push office working. “What happens if you refuse to return to office?” asked another.

The three-day model

Since the start of the pandemic, how someone chooses to work has been a personal decision for many office workers. Even for those chief executives who are not desperate to get everyone back into an office, the coming weeks are an opportunity to lay out formal policies on what the future of work will look like.

Some chief executives have emphasized the importance of face-to-face interaction for team work, company culture and junior employee training. But in many cases the explanations they have given about why the office is important have been vague.

If you ask for three days a week, you need to be able to explain why. To what end?

STEPHAN SCHOLL, CHIEF EXECUTIVE, ALIGHT SOLUTIONS

Stephan Scholl, chief executive of Alight Solutions, a cloud-based technology and services provider, says he had been reluctant to make office days compulsory. “If you ask for three days a week, you need to be able to explain why. To what end? This is what is frustrating about some of my peers.”

|

| 1932 |

“There is not one right way of working,” says Ethan Bernstein, an organizational behaviour expert at Harvard Business School. When everyone had to work at home full time it was easy for managers, as there was no other option. It is the hybrid model that is proving more difficult because of the endless ways work can take place. “This is a moment, yes, in trying to define what hybrid means,” he says. However, as there is little data to help companies chart a path, that often means the preferences of some — likely senior — staff will drive how a corporation behaves.

Amanda Cusdin, chief people officer at software company The Sage Group Plc, says that “human connection is still the most important thing” in many workplaces, especially for the 2,000 people the company recruited during lockdown who wanted to build connections.

The company has decided on a hybrid working model where each team determines the days they are in the office and staff are generally positive that they do not have to work five days a week in the office, she says. “At the same time, no one wants to come back to an empty building, so we need to have a critical mass present.”

Employees are welcomed back to work with breakfast

in the cafeteria at the Chicago Google offices in April.

PHOTO BY SCOTT OLSON/GETTY IMAGES

In the early stages of the pandemic, bosses focused on physical wellbeing, mental health and flexibility at work so employees could tend to the demands of sick relatives and home-schooling.

Then, after the rollout of vaccines, many tried to persuade workers back by offering perks — from free lunches and Uber rides to after-work drinks events, massages and employee discounts for local retailers. Goldman laid on afternoon concerts for its staff.

Envoy, a San Francisco workplace platform, now offers a shuttle service, a carpool program and a US$200 monthly commuting subsidy to persuade employees to come in for its desired three days a week. In the office, there are free bagel and fruit breakfasts, “snacks everywhere” and a happy hour once a month, says Annette Reavis, Envoy’s chief people officer, adding that dog owners are encouraged to bring their pets to work so they do not have to pay for dog walkers. “We’re trying to remove some of that financial burden,” she says, “but also build community.”

However, while some employers continue to prioritize workplace benefits, others are taking a harder-nosed approach, which is coinciding with new budgetary constraints as companies prepare for a potential economic downturn.

Even Reavis acknowledges that those who remain at home should be thinking about the risk that managers are more likely to offer promotions and pay rises to the people closest to them. “Proximity bias is real,” she says, “and it’s only going to get worse in the next six to 12 months.”

Proximity bias is real and it's only going to get worse in the next six to 12 months

ANNETTE REAVIS, CHIEF PEOPLE OFFICER, ENVOY

The domino effect

Among the industries that depend heavily on filled corporate buildings, executives are watching the next few weeks closely, but many are cautious about predicting a surge in returning staff — especially after some made similar forecasts at the same time last year.

Sweetgreen, the U.S. salad chain which has two-thirds of its outlets in urban areas, has blamed “a slower-than-expected return to office and an erratic urban recovery” as it cut its full-year sales forecast. Traffic to stores such as its branch at the World Trade Center should pick up after Labour Day, says chief financial officer Mitch Reback, but “we felt that way a year ago, and the world felt that way two years ago.”

Huge shifts in office rents, occupancy and leases have already had a huge effect on office building cash flows, say academics from the NYU Stern School of Business and Columbia Business School. The one-third fall in the value of New York office buildings in the first year of the pandemic heralds a longer-term “office real estate apocalypse” equating to a US$50-billion cut to the value of New York’s offices and a US$500-billion blow to the industry nationwide.

A person stands outside the Bank of America Tower in New York City.

PHOTO BY AMIR HAMJA/BLOOMBERG

Google’s Community Mobility Report, which charts movement trends across places such as offices, clothes shops, Tube stations, pharmacies and supermarkets found that compared to pre-pandemic levels, retail and recreation footfall was still down 26 per cent in the City of London. For the supermarket and pharmacy category it has fallen nearly 60 per cent. Both of these correspond to a 40 per cent reduction in travel to workplaces.

Yet despite the growing pressure from some bosses, many office workers seem to show little appetite for abandoning new ways of living they are rather enjoying. They are more available to their families, have eliminated hours of travel and found new freedoms through distance from their line managers.

The most recent report by Advanced Workplace Associates, a consultancy, on global hybrid working, which is based on nearly 80,000 employees across 80 offices in 13 countries, showed that on an average day two-thirds of desks are unused and just over a quarter of people are coming into the offices, with the attendance figure dropping to 12 per cent on Fridays.

In the U.S., a new Gallup poll suggests only 22 per cent of the employees surveyed who could work remotely are currently on site for most of the week and more than 90 per cent have no desire to return to full-time office work. Strikingly, the percentage of those currently on site who want to work exclusively from home has doubled since October 2021.

Some employers have already embraced the new reality by advertising fully virtual jobs or even opening up satellite offices to meet now-distributed workforces.

Industry observers say forcing people back to the office is a fruitless endeavour. The world has changed and companies need to adapt if they seek to retain talent in a tight labour market particularly in the U.S. and U.K. that, for now, will offer them alternatives if they walk away.

“Employees will just say no,” says Francke. “They know flexible working works and they will resent you for telling them they need to be at the office.”

Additional reporting by Joshua Franklin

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd.

RETURN TO OFFICE

The Professional Try-Hard Is Dead, But You Still Need to Return to the Office

In the era of the Great Resignation, remote work, and “quiet quitting,” general disillusionment with white-collar striving has gone mainstream. The managerial set has yet to be CC’d.

BY DELIA CAI

SEPTEMBER 6, 2022

PHOTO FROM SHUTTERSTOCK.

During my first job in media in the late 2010s, I was a glorified PowerPoint assembler on a magazine’s marketing team, where we spent our days figuring out what kinds of stories and topic areas corporate brands liked to put their advertising next to. One of the most popular themes was what we slickly called “The Future of Work”—a catchphrase cribbed from the marketing and MBA-swinging circles invested in forecasting all the exciting ways corporate life would change amidst peak millennialification of the workforce. We knew advertisers loved the idea of fashioning themselves as part of this revolution, and I still remember how I’d decorate those PowerPoints with stock images of ultramodern office spaces and stylish, suited figures in carefully varied skin tones. It never occurred to me, or my colleagues, or these brands, to wonder if the real future of work might actually look like something far more radical.

Roughly one pandemic later, there has been such an abrupt rupture in the way we work—not to mention how we think and talk about it—that we grasp at new taxonomies for the disillusionment with the hustle: It’s millennial burnout, it’s the “Age of Anti-Ambition,” it’s the Great Resignation. As the labor market has tightened and the labor movement regains cachet, living “under capitalism” has become a default punchline. The antiwork subreddit is the hottest club in town. Ambitious women are reportedly done with girlbossing (now in vogue: girlresting) and The Wing has officially crashed; it appears Kim Kardashian’s assessment that nobody wants to work these days was correct, because even Serena Williams can’t have it all. Of those who have given notice, there’s a predictable amount of regret: just not, it seems, amongst the clear majority.

Nowhere has this work-life reckoning been analyzed more obsessively than in the realm of white-collar work, where a confrontation with its privileges (being able to Zoom in to meetings from home) and indignities (having to grimace for the camera through all two hours of said Zoom meeting) has made for quite a lot of soul-searching. Consider the pandemic television shows that have elicited the buzziest (virtual) watercooler talk amongst the very-online class. Recent series like The Bear and Abbott Elementary depict workplaces that resist any administrative beveling of the messy realities of serving food and teaching children, which the Slack-dependent then watch with fetishistic awe. Meanwhile, we observe the infantilizing melon parties of Severance and the jargon-happy, nihilistic earners of Industry with an uneasy sense of identification. (Wait, is this fucking play about us?)

And so the future of white-collar work has morphed from an advertiser-friendly thought exercise to an existential question with a daily subset of moral riddles: Is that an illicit midday nap, or is it just work-life balance? Is it really the end of work friends, or is it just that a defensive herd mentality is no longer crucial to getting through the day? Is it worse to work on vacation, or to have a little vacation at work? Is the delivery bot lost in the woods, or is he finally free?

Take the latest debate on “quiet quitting” as a trendy, divisive term for what Anthony Klotz, the management professor who inadvertently coined “the great resignation” back in May 2021, links to the not-new concepts of worker disengagement and withdrawal. “All jobs have core elements of the job, which we call in-role performance…‘quiet quitting’ is quitting everything beyond that, which we call citizenship behaviors—going above and beyond the call of duty,” explains Klotz. Whatever moniker you give it, there’s now increasingly accepted room for the idea that you might step off the professional gas pedal in order to protect your well-being and even sense of identity. “People are talking about it as a mindset shift,” says Klotz, who has studied resignations for more than a decade. “Realizing like, I’ve become kind of a unidimensional person…I’m quiet quitting mentally to make room for me to be more than just a worker.” (Klotz allows for the record to show that he, too, was not immune to the Big Quittening’s reach; earlier this year, he resigned from his post at Texas A&M University for a new job teaching at University College London.)

Over the past months, as corporate employers attempt once more to marshall back-to-school sentimentality (not to mention a collective, CDC-sanctioned shrug re: coronavirus itself) to coax everyone back into those expensive real estate holdings, the fight over return-to-office is just one of the questions that foreground not only predictable tensions between worker and boss, but also between anyone who still believes in the physical office—and all its trappings—as a desired state of “normalcy,” versus everyone else who no longer does.

We can call the former, if you’re feeling derisive, the “professional try-hards;” I’d love to be flip and just say that, at this point in planetary decline, anyone who’s a little too interested in emails and Google Docs basically counts as a try-hard, but there’s a specific category of salaryfolk and company leadership provoking a justifiable kind of scorn. The professional try-hard I’m talking about is someone who, in the year 2022, still earnestly and performatively buys into the white-collar hustle and prides themselves on it. You know this person. They’re a cross between a teacher’s pet and a supply-room narc; if they’re not already a manager, they certainly aim to be one day. While everyone else got with the program that trying hard at work—against a political and national backdrop that feels like daily, endless crisis—is ridiculous, or worse, meaningless, these guys (it’s not exclusively a male thing, of course, but I’m not not being gendered on purpose) haven’t quite gotten with the program.

It’s Malcolm Gladwell waxing emotional about how much he loves return-to-office and pleading, “Don’t you want to feel part of something?” as if the man has never heard of, like, recreational softball. It’s Mark Zuckerberg reportedly getting mad about an employee asking if Meta Days (extra vacation days introduced during the pandemic) are still on this year because, shouldn’t the pleasure of working for Meta be enough? It’s any number of investor-type herbs who’ve been warning about how quiet quitting will cause you to lose out on x dollar amount of earnings later in life—that retirement yacht isn’t going to fund itself with the tears of your absent children, you know! It’s Braden Wallake, better known as the Crying CEO, who posted a photo of himself in tears on LinkedIn (of course it was on LinkedIn) in an attempt to score sympathy points for the vewy hward jwob of being in charge (chwarge?), only to turn himself into a viral joke. Let that tragic selfie tell you everything you need to know about how badly the try-hards are losing their grip.

“I don’t believe he was actually crying,” says public relations CEO and remote-work cheer captain Ed Zitron, when I ask for his take on the Wallake debacle. “I know exactly what he was doing there—this was his way of heading off layoff messaging at the pass. He was trying to make himself look good…he was obsessed with the aesthetics of all of it.” For Zitron, whose bylines at The Atlantic, Insider, and his personal newsletter have made him the internet’s most unapologetic executive-class advocate of remote work, a regular torching of cringey professional-try-hard behavior has become something of a second career.

In Zitron’s view, as he wrote last summer in “Why Managers Fear a Remote-Work Future,” the battle over return-to-office is really about the way remote work rightfully disempowers a certain type of managerial creature—those who’ve gotten by on office diplomacy and the fine art of appearing busy and important, but not necessarily useful. As he sees it, the physical office space gave the advantage to anyone whose job was making sure you’re doing yours; no wonder professional try-hards are so obsessed with forcing everyone else back. “I believe there is a large chunk of extremely performative work that is having a midlife crisis right now,” Zitron says. “Executives are slowly realizing they don’t do as much and they may not be deserving of all of this. I think they want attention. They used to go into the office and be like, ‘Hello, peon! Look at me! You have to talk to me! You have to say things that make me happy, or I’ll fire you.’” (For the record, Zitron’s PR agency has been remote since 2012: “I’m in my pajamas right now, by the way,” he gleefully informs me over our midday call).

Though his views are far less pitchfork-and-torch-y, Klotz, the management professor, agrees that there is a sense of threat posed by the changed landscape of the workplace for the corner-office cohort. “I don’t think it’s nefarious or anything negative on the part of these leaders,” he explains. They’re just following the playbook that’s gotten them—and the economy—this far, reasoning, ‘If we would all just get back together, we can get back on track like it was in 2019’—which was a banner year for most companies, by the way,” Klotz says. “But you have workers who are saying, ‘All that’s good and well, but this is better for our lives.’” In an email, Klotz adds that, yes, of course employees resist having any workplace benefit (like the flexibility of remote work) taken away, but research has also shown that employees push back less if given a fair explanation. “I think that’s part of the tension right now,” he explains. “Employees who like working remotely but are being asked to return to the office are asking their leaders WHY.”

Why, indeed. It’s the question of the hour raised with every morning alarm, every increasingly stern RTO email, every not-so-theoretical conversation I have had with my editor about this strange evolution of work, as my own office began to shift from pleasantly voluntary in-person meetings to required (part-time) attendance. Here I will risk a degree of try-hardist edging to say that I’d previously enjoyed spending Tuesdays at my Manhattan desk as a lifestyle choice, employer-grade air conditioning being one of the few things you can’t absorb over videoconference. But why did my feelings about the office shift from neutral to total disorientation the minute it became a fulfillment of some external requirement, some other decision-maker’s ruling, rather than an expression of my agency as a working adult?

I felt the dissonance on a visceral level when I was paging through an advance copy of Smart Brevity, a new handbook about “the power of saying more with less,” to be published September 20 by Jim VandeHei, Mike Allen, and Roy Schwartz, veterans of Politico and founders of Axios—two very good news outlets that have prided themselves on the particular formal innovations of blogging (Politico), bullet points (Axios), and constant exhortations for their audience to “be smart” (also Axios).

The book, which will now serve as something of a victory lap following last month’s $525 million sale of Axios to Cox Enterprises, touts the importance of direct, well-formatted communication for earning the trust and respect of your audience/employees, then promises to teach readers how to become miniature crusaders of clarity via a “revolutionary system and strategy” that the authors have dubbed “Smart Brevity.” It’s a well-timed hook: For anyone in the managerial set currently at a loss for how to wield influence sans in-person meetings, the chance to learn the secret to writing more powerful emails is certainly appealing. And you could do a lot worse than turning to three successful journalists for a primer on communication skills.

The problem, however, is that most corporate communications suck because most people simply aren’t professional writers, and in lieu of figuring out how to cram an MFA’s worth of actual writing advice into 200 pages, Smart Brevity resorts to consultant-class platitudes, like “singling out the person you want to reach clarifies things big-time,” and recommendations like “do a real gut check. Is this point or detail or concept essential?” Try as the authors might to rebrand a headline as a “tease” and bottom-line takeaways as an “axiom,” Smart Brevity’s attempts to pass off foundational concepts of good writing into some secret, proprietary technology often just feel silly; the exhortations on bullet point/GIF implementation and a whole chapter dedicated to emoji use veer toward insulting. A good portion of the book consists of before-and-after examples where some imagined long-winded paragraph gets made over in the Smart Brevity style; the resulting effect is not so much a lesson on succinctness as it is a clue about which types of people are socially encouraged to communicate in pings of authoritative masculine curtness.

I’d be lying if I didn’t emit the occasional juvenile laugh over lines like “Brevity is confidence. Length is fear,” and explanations for “STRONG” one-syllable words versus “WEAK” words (Do one of you guys want to tell me why the verb “bitch” is listed as an example of the former?). For a book obsessed with clarity, it’s hilariously redundant. But that isn’t the point, is it? (Who really thinks that the secret to workplace success lies in Slack’s Giphy library?) The irony, of course, is that Politico and Axios made their core business and reputation by providing subscribers news-making and actionable scoops—the snazzy, emoji-laden bullet-pointing of the news is merely branding. And that branding, apparently, is the actual point. This is a book with a snappy name and zippy catchphrases meant for white-collar strivers to carry around, or, as Zitron might say, a matter of aesthetics. It will do just as well to telegraph that you’re interested in solving the awesome mystery of effective communication as to actually bother with the work of it. It’s perfect professional-try-hard fare that concerns itself very little with how the wordiness of your speeches is probably not the biggest factor in how disgruntled your workplace feels about RTO.

What ties Smart Brevity, the Crying CEO, and general corporate try-hardism all together is this shared preoccupation with the appearance of hypercompetence over the actual thing. Why concern yourself with the complex factors causing employee burnout or worker disillusionment or midday napping when you’ve convinced yourself (and are attempting to reconvince your workers) that it’s just a matter of writing the most poetic (but also effective) LinkedIn post?

What’s clear—and what’s behind the reason that professional try-hards are flailing so fantastically—is that the very concept of corporate competence itself has become a joke. The ideals that white-collar striving is built upon have started to crumble: Imagine believing in true “innovation” in a world where Meta, formerly the most exciting company on earth, is reduced to hitting copy and paste. Imagine still buying into the corporate ladder in any sector where performance evaluations might be rife with racial disparities, or where the executives have essentially admitted on the stand that their entire industry is just a game of roulette. Imagine having faith at all in any idea of “corporate good” when the guy celebrated for years as the “one moral CEO in America” is now the subject of a rape investigation (that CEO has denied the allegations). Just last month, Adam Neumann, the disgraced WeWork founder whose implosion was so well-documented that it got turned into prestige television, reportedly received a $350 million second chance for pretty much the same idea he rode to ruin last time.

Imagine, in other words, believing anyone in charge knows what they’re doing. But okay, sure, sic the productivity-management software on everyone else to make sure we’re not online shopping a touch too much.

“People are waking up to this disenfranchisement, but I think it’s important to realize why,” Zitron sighs. “During COVID, we got to see that companies are more than willing to cut your asses out and reap massive profits a year later. The government treated companies better than they treated people. And what did people get? Maybe a check of $1,400.” He adds: “People turned around and were like, You know what? I’ve been working my ass off thinking it would get me somewhere. Why should I go above and beyond?”

So there may just be power in the disillusionment—for now:

“Usually in the world of work, organizational leaders change and followers are the ones who have to adjust,” says Klotz. “This is the moment where it flipped a little bit. A lot of employees and a lot of the world of work is saying to leaders, ‘We’ve gotten this glimpse into this world of work—this future of work—that is better for us. Could you please adjust?’” He pauses. “And that’s tough, because you’re asking the people with the power to adjust.”

And, mind you, this is all before the next economic downturn hits.

Delia Cai

SENIOR VANITIES CORRESPONDENT

Delia Cai is a senior Vanities correspondent at Vanity Fair, covering culture and celebrity. She joined V.F. after writing the “Deez Links” newsletter for five years. Delia lives in Brooklyn, and her forthcoming novel, Central Places, will be published with Ballantine Books.