Forrest Brown

CNN

Digital

Published Dec. 21, 2022

For the past six months, the days have grown shorter and the nights have grown longer in the Northern Hemisphere. But that's about to reverse itself.

Winter solstice 2022, the shortest day of the year and the official first day of winter, is on Wednesday, December 21 (well, for a decent chunk of the world anyway). How this all works has fascinated people for thousands of years. Climate Barometer newsletter: Sign up to keep your finger on the climate pulse

First, we'll look at the science and precise timing behind the solstice. Then we'll explore some ancient traditions and celebrations around the world.

The science and timing behind a winter solstice

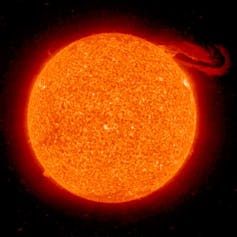

The winter solstice marks the shortest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere when the sun appears at its most southerly position, directly overhead at the Tropic of Capricorn.

The situation is the reverse in the Southern Hemisphere, where only about 10% of the world's population lives. There, the December solstice marks the longest day of the year -- and the beginning of summer -- in places like Argentina, Madagascar, New Zealand and South Africa.

The winter solstice marks the shortest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere when the sun appears at its most southerly position, directly overhead at the Tropic of Capricorn.

The situation is the reverse in the Southern Hemisphere, where only about 10% of the world's population lives. There, the December solstice marks the longest day of the year -- and the beginning of summer -- in places like Argentina, Madagascar, New Zealand and South Africa.

When exactly does it occur?

The solstice usually -- but not always -- takes place on December 21. The date that the solstice occurs can shift because the solar year (the time it takes for the sun to reappear in the same spot as seen from Earth) doesn't exactly match up to our calendar year.

If you want to be super-precise in your observations, the exact time of the 2022 winter solstice will be 21:48 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) on Wednesday, according to EarthSky.org and Farmers' Almanac. That's almost six hours later than last year's time.

Below are some examples of when 21:48 UTC will be for various local times in places around the world. Because of time zone differences, the vast bulk of Asia will mark the winter solstice on Thursday, December 22.

• Tokyo: 6:48 a.m. Thursday

• Hanoi, Vietnam: 4:48 a.m. Thursday

• New Delhi: 3:18 a.m. Thursday

• Istanbul: 12:48 a.m. Thursday

• Jerusalem: 11:48 p.m. Wednesday

• Copenhagen, Denmark: 10:48 p.m. Wednesday

• Charlotte, North Carolina: 4:48 p.m. Wednesday

• Winnipeg, Manitoba: 3:48 p.m. Wednesday

• San Francisco: 1:48 p.m. Wednesday

• Honolulu: 11:48 a.m. Wednesday

To check the timing where you live, the website EarthSky has a handy conversion table for your time zone. You might also try the conversion tools at Timeanddate.com, Timezoneconverter.com or WorldTimeServer.com.

What places see and feel the effects of the winter solstice the most?

Daylight decreases dramatically the closer you are to the North Pole on December 21.

People in balmy Singapore, just 137 kilometres or 85 miles north of the equator, barely notice the difference, with just nine fewer minutes of daylight than they have during the summer solstice. It's pretty much a 12-hour day, give or take a few minutes, all year long there.

Much higher in latitude, Paris still logs in a respectable eight hours and 14 minutes of daylight to enjoy a chilly stroll along the Seine.

The difference is more stark in frigid Oslo, Norway, where the sun will rise at 9:18 a.m. and set at 3:12 p.m., resulting in less than six hours of anemic daylight. Sun lamp, anyone?

Residents of Nome, Alaska, will be even more sunlight deprived with just three hours and 54 minutes and 31 seconds of very weak daylight. But that's downright generous compared with Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. It sits inside the Arctic Circle and won't see a single ray of sunshine.

What causes the winter solstice to even happen?

Because Earth is tilted on its rotational axis, we have changing seasons. As the planet moves around the sun, each hemisphere experiences winter when it's tilted away from the sun and summer when it's tilted toward the sun.

Scientists are not entirely sure how this occurred, but they think that billions of years ago, as the solar system was taking shape, the Earth was subject to violent collisions that caused the axis to tilt.

The equinoxes, both spring and fall, occur when the sun's rays are directly over the equator. On those two days, everyone everywhere has a nearly equal length of day and night. The summer solstice is when the sun's rays are farthest north over the Tropic of Cancer, giving us our longest day and the official start of summer in the Northern Hemisphere.

Winter solstice traditions and celebrations

It's no surprise many cultures and religions celebrate a holiday -- whether it be Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa or pagan festivals -- that coincides with the return of longer days.

Ancient peoples whose survival depended on a precise knowledge of seasonal cycles marked this first day of winter with elaborate ceremonies and celebrations. Spiritually, these celebrations symbolize the opportunity for renewal.

"Christmas takes many of its customs and probably its date on the calendar from the pagan Roman festivals of Saturnalia and Kalends," Maria Kennedy, assistant teaching professor in the Department of American Studies at Rutgers University, told CNN Travel in an email.

Saturnalia started on December 17 and Kalends started on January 1, said Kennedy, who specializes in Christmas studies.

Citing academic research, Kennedy said early founders of the Christian church condemned the practices of these holidays, but their popularity endured. Christian observance of Christmas eventually aligned around the same time in the calendar even though there's no specific date set in the Gospels for the birth of Jesus.

Here's more on some of those ancient customs:

In the Welsh language, "Alban Arthan" means for "Light of Winter," according to the Farmers' Almanac. It might be the oldest seasonal festival of humankind. Part of Druidic traditions, the winter solstice is considered a time of death and rebirth.

Newgrange, a prehistoric monument built in Ireland around 3200 BC, is associated with the Alban Arthan festival.

In Ancient Rome, Saturnalia lasted for seven days. It honoured Saturn, the Roman god of agriculture.

The people enjoyed carnival-like festivities resembling modern Mardi Gras celebrations and even delayed their war-making. Slaves were given temporary freedoms, and moral restrictions were eased. Saturnalia continued into the third and fourth centuries AD.

It's not just ancient Europeans who marked the annual occasion. The Dongzhi Winter Solstice Festival has its roots in ancient Chinese culture. The name translates roughly as "extreme of winter."

They thought this was the apex of yin (from Chinese medicine theory). Yin represents darkness and cold and stillness, thus the longest day of winter. Dongzhi marks the return yang -- and the slow ascendance of light and warmth. Dumplings are usually eaten to celebrate in some East Asian cultures.

Many places around the world traditionally hold festivals that honour the winter solstice. A few of them include:

Montol Festival

Better known for pirates than the solstice, the town of Penzance on the southwest coast of England revived the delightful tradition of a Cornish processional -- along with dancing, mask-wearing, singing and more.

Stonehenge

The UK's most famous site for solstice celebrations is Stonehenge. On the winter solstice, visitors traditionally enter the towering, mysterious stone circle for a sunrise ceremony run by local pagan and druid groups.

The English Heritage Society says the 2022 celebration will be held on Thursday, December 22. It will be live-streamed on its YouTube channel.

Lantern Festival

In Canada, Vancouver's Winter Solstice Lantern Festival is a sparkling celebration of solstice traditions spread across the Granville Island, Strathcona and Yaletown neighbourhoods.

CNN's Katia Hetter and Autumn Spanne contributed to this article

These three images from NOAA's GOES East (GOES-16) satellite show us what Earth looks like from space near the winter solstice. The images were captured about 24 hours before the 2018 winter solstice. (NOAA)

Here’s why the winter solstice is significant in cultures across the world

By —Molly Jackson, The Conversation

Journey of the sun

First things first: What is the winter solstice?

For starters, it’s not the day with the latest sunrise or the earliest sunset. Rather, it’s when “the sun appears the lowest in the Northern Hemisphere sky and is at its farthest southern point over Earth,” wrote William Teets, an astronomer at Vanderbilt University. “After that, the sun will start to creep back north again.”

In the Southern Hemisphere, meanwhile, Dec. 21, 2022 marks the summer solstice. Its winter solstice will arrive June 21, 2023, the same day the Northern Hemisphere celebrates its summer solstice.

“Believe it or not,” Teets added, “we are closest to the sun in January”: a reminder that seasons come from the Earth’s axial tilt at any given time, not from its distance from our solar system’s star.

By —Molly Jackson, The Conversation

Science Dec 21, 2022

If you’ve already spend hours shoveling snow this year, you may be dismayed to realize that technically, it’s not yet winter. According to the astronomical definition, the season will officially begin in the Northern Hemisphere on Dec. 21, 2022: the shortest day of the year, known as the winter solstice.

The weeks leading up to the winter solstice can feel long as days grow shorter and temperatures drop. But it’s also traditionally been a time of renewal and celebration – little wonder that so many cultures mark major holidays just around this time.

Here are four things to know about the solstice, from what it really is to how it’s been commemorated around the world.

If you’ve already spend hours shoveling snow this year, you may be dismayed to realize that technically, it’s not yet winter. According to the astronomical definition, the season will officially begin in the Northern Hemisphere on Dec. 21, 2022: the shortest day of the year, known as the winter solstice.

The weeks leading up to the winter solstice can feel long as days grow shorter and temperatures drop. But it’s also traditionally been a time of renewal and celebration – little wonder that so many cultures mark major holidays just around this time.

Here are four things to know about the solstice, from what it really is to how it’s been commemorated around the world.

Journey of the sun

First things first: What is the winter solstice?

For starters, it’s not the day with the latest sunrise or the earliest sunset. Rather, it’s when “the sun appears the lowest in the Northern Hemisphere sky and is at its farthest southern point over Earth,” wrote William Teets, an astronomer at Vanderbilt University. “After that, the sun will start to creep back north again.”

In the Southern Hemisphere, meanwhile, Dec. 21, 2022 marks the summer solstice. Its winter solstice will arrive June 21, 2023, the same day the Northern Hemisphere celebrates its summer solstice.

“Believe it or not,” Teets added, “we are closest to the sun in January”: a reminder that seasons come from the Earth’s axial tilt at any given time, not from its distance from our solar system’s star.

Ancient astronomy

Many Americans picturing winter solstice celebrations may immediately think of Stonehenge, but cultures have honored the solstice much closer to home. Many Native American communities have long held solstice ceremonies, explained University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign scholar Rosalyn LaPier, an Indigenous writer, ethnobotanist and environmental historian.

“For decades, scholars have studied the astronomical observations that ancient indigenous people made and sought to understand their meaning,” LaPier wrote. Some societies in North America expressed this knowledge through constructions at special sites, such as Cahokia in Illinois – temple pyramids and mounds, similar to those the Aztecs built, which align with the sun on solstice days.

“Although some winter solstice traditions have changed over time, they are still a reminder of indigenous peoples’ understanding of the intricate workings of the solar system,” she wrote, and their “ancient understanding of the interconnectedness of the world.”

Dazzling light

Rubén Mendoza, an archaeologist at California State University, Monterey Bay, made an accidental discovery years ago at a mission church. In this worship space and many others that Catholic missionaries built during the Spanish colonial period, the winter solstice “triggers an extraordinary rare and fascinating event,” he explained: “a sunbeam enters each of these churches and bathes an important religious object, altar, crucifix or saint’s statue in brilliant light.”

Winter solstice illumination of the main altar tabernacle of the Spanish Royal Presidio Chapel, Santa Barbara, Calif. Rubén G. Mendoza, CC BY-ND

These missions were built to convert Native Americans to Catholicism – people whose cultures had already, for thousands of years, celebrated the solstice sun’s seeming victory over darkness. Yet the missions incorporated those traditions in a new way, channeling the sun’s symbolism into a Christian message.

“These events offer us insights into archaeology, cosmology and Spanish colonial history,” Mendoza wrote. “As our own December holidays approach, they demonstrate the power of our instincts to guide us through the darkness toward the light.”

Victory over darkness

Our next story goes halfway around the world, describing the Persian solstice festival of Yalda. But it’s also an American story. Growing up in Minneapolis, anthropologist Pardis Mahdavi explained, she felt a bit left out as neighbors celebrated Hanukkah and Christmas. That’s when her grandmother introduced her to their family’s Yalda traditions.

Millions of people around the world celebrate Yalda, which marks the sunrise after the longest night of the year. “Ancient Persians believed that evil forces were strongest on the longest and darkest night of the year,” wrote Mahdavi, who is now provost at the University of Montana. Families stayed up throughout the night, snacking and telling stories, then celebrating “as the light spilled through the sky in the moment of dawn.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Many Americans picturing winter solstice celebrations may immediately think of Stonehenge, but cultures have honored the solstice much closer to home. Many Native American communities have long held solstice ceremonies, explained University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign scholar Rosalyn LaPier, an Indigenous writer, ethnobotanist and environmental historian.

“For decades, scholars have studied the astronomical observations that ancient indigenous people made and sought to understand their meaning,” LaPier wrote. Some societies in North America expressed this knowledge through constructions at special sites, such as Cahokia in Illinois – temple pyramids and mounds, similar to those the Aztecs built, which align with the sun on solstice days.

“Although some winter solstice traditions have changed over time, they are still a reminder of indigenous peoples’ understanding of the intricate workings of the solar system,” she wrote, and their “ancient understanding of the interconnectedness of the world.”

Dazzling light

Rubén Mendoza, an archaeologist at California State University, Monterey Bay, made an accidental discovery years ago at a mission church. In this worship space and many others that Catholic missionaries built during the Spanish colonial period, the winter solstice “triggers an extraordinary rare and fascinating event,” he explained: “a sunbeam enters each of these churches and bathes an important religious object, altar, crucifix or saint’s statue in brilliant light.”

Winter solstice illumination of the main altar tabernacle of the Spanish Royal Presidio Chapel, Santa Barbara, Calif. Rubén G. Mendoza, CC BY-ND

These missions were built to convert Native Americans to Catholicism – people whose cultures had already, for thousands of years, celebrated the solstice sun’s seeming victory over darkness. Yet the missions incorporated those traditions in a new way, channeling the sun’s symbolism into a Christian message.

“These events offer us insights into archaeology, cosmology and Spanish colonial history,” Mendoza wrote. “As our own December holidays approach, they demonstrate the power of our instincts to guide us through the darkness toward the light.”

Victory over darkness

Our next story goes halfway around the world, describing the Persian solstice festival of Yalda. But it’s also an American story. Growing up in Minneapolis, anthropologist Pardis Mahdavi explained, she felt a bit left out as neighbors celebrated Hanukkah and Christmas. That’s when her grandmother introduced her to their family’s Yalda traditions.

Millions of people around the world celebrate Yalda, which marks the sunrise after the longest night of the year. “Ancient Persians believed that evil forces were strongest on the longest and darkest night of the year,” wrote Mahdavi, who is now provost at the University of Montana. Families stayed up throughout the night, snacking and telling stories, then celebrating “as the light spilled through the sky in the moment of dawn.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.