By MATTHEW ROZSA

SALON

As William Blake famously wrote, "To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower" is to "Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour." But as innocuous, ubiquitous and just plain mundane sand can be, it can also be the source of significant conflict and violence while often being extracted to the detriment of our planet.

When the term "conflict mineral" is used, people often think of precious stones like rubies or valuable fuels like coal. Certainly the industry of mining those rocks is fraught with controversy and peril, yet even the most seemingly ubiquitous minerals can serve as the source of conflict. But is sand really in the same category as cobalt and blood diamonds?

"Whilst not normally listed as a conflict mineral, the extraction of sands and gravels in some countries clearly has characteristics of being such."

According to a 2022 United Nations report, sand is the second-most consumed resource on Earth, surpassed only by water. And just like water, humans are consuming sand at an unsustainable rate — increasing by 6 percent every year, to be exact. As they do, they leave behind a wake of polluted rivers, severe droughts, shrinking aquifers and flooded communities. One statistic especially stands out: China alone has used more construction sand in the last few years than the United States used in the entire 20th century.

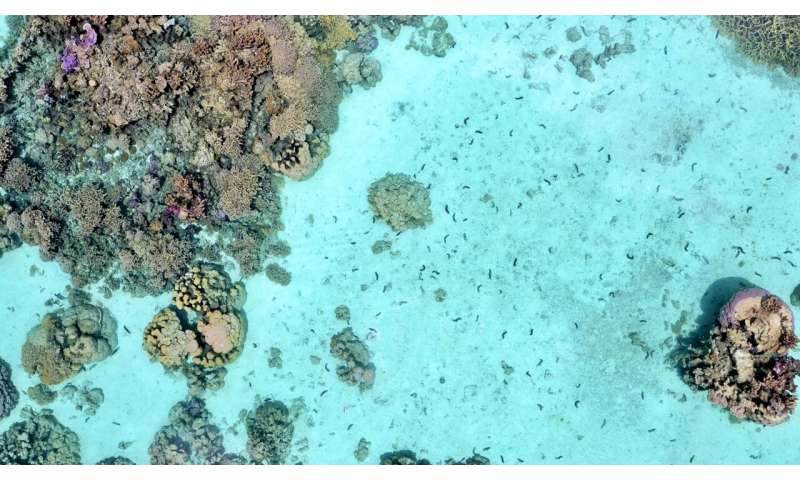

Even worse, sand is so valuable that it frequently becomes the source of tension. This is partially due to the fact, as corporations dredge up sand from the sea, they start altering local geography such as the shape of coastlines and the presence of small islands. Because sand miners are often unregulated, their activities can destroy local ecosystems, contaminate potable water for nearby communities and destroy entire agricultural sectors.

If all of this seems like a whole lot of ado over a common substance, guess again.

Related

Advocates demand halt to uranium mine near the Grand Canyon

"In some regions, illegal sand and gravel mining is associated with crime syndicates, coercion and violence, and many other related social impacts," James Leonard Best, a professor of sedimentary geology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, told Salon by email, adding that there have even been reported of so-called "sand mafias." "Whilst not normally listed as a conflict mineral, the extraction of sands and gravels in some countries clearly has characteristics of being such."

This is because, quite simply, every human being alive today relies on products that are at least in large part made from sand. Most people reading this article are doing so with the help of sand.

"Sand is used in many products such as smartphone screens, glass bottles and many other products but sand is predominantly used in the construction industry," Jakob Kløve Keiding from the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) told Salon by email. "Aggregates (sand, gravel and rocks) are a granular material used in construction in many ways such ready mixed concrete, precast concrete, asphalt products, and structural (unbound) materials. Aggregates have superior mechanical properties, good durability and are low cost products compared to many other materials that could potentially be used instead."

Best further elaborated on sand's multifaceted properties.

"Sand is a key ingredient of concrete globally, and in addition is a major material used for landfill and reclamation: many areas on which urbanization proceeds require infill of low/wet areas in order for construction to proceed," Best explained. "Dredged sands along coasts are also used in coastal protection works, construction of flood defenses and schemes to mitigate coastal erosion."

Best also pointed out that high-quality silica sands are widely used to manufacture glass for products like medical vials, microchips and glass panels. "As such, sand and gravels underpin our modern economies, and also are key in many aspects of the UN Sustainable Development Goals," Best said.

"Sand and gravels underpin our modern economies."

Yet precisely because sand can be used for so many things, it is particularly vulnerable to being overused. As Keiding explained, even though sand may seem like a limitless resource to anyone who has hiked through a desert, it is in fact quite finite. Even worse, human beings have barely scratched the surface of mapping our sand allocations on a global level.

"It is important to stress that the aggregates sector is by far the largest amongst the non-energy extractive industries," Keiding told Salon, "so the demand is really massive and sand is occurring in different qualities. So when we talk about shortage, it is demand of certain high quality types — for instance used in concrete — that is critical and where there is scarcity." Keiding added that "the resources are unevenly distributed, so certain areas and regions can locally have significantly problems with the availability of enough resources (transportation of sand and gravel is very costly)."

Sand also leads to conflict because it can be mined from a diverse range of locales. Even though one would think finding useable sand is as easy as wandering through the Arabian desert, the unfortunate reality is that Arabian desert sand is too fine to be easily used for construction and other commercial endeavors.

In contrast, sand found in shallow marine environments and rivers has rougher edges and therefore can be properly used for construction (although as Best warned, sand acquired from shallow marine environments can be problematic when it comes to making strong concrete because of the high salt concentrations). Sand extracted from ancient geological reserves like sand quarries has likewise not been smoothed out by exposure to wind and the elements.

In short, while only certain types of sand possess the correct physical properties to be commercialized, that type of sand can be found in a wide range of locations. That in turn increases the environmental damage that can be caused by sand mining, as well as the conflicts that inevitably ensue when large groups of humans seek profit from a natural resource.

"Market price can dictate that use of local sands is far more feasible than those from further away, and thus in areas that are experiencing rapid economic growth, and especially urbanization, the demands for sand has increased greatly," Best wrote to Salon. "This can create scarcity in some areas, drive up the price of sand, which then feeds back to increase the economic feasibility of mining sands in modern environments and ancient sediments. Excessive sand mining can cause a range of environmental impacts to rivers and coasts, with a wide range of socio-economic issues associated with this (ranging from degradation of environments, to human migration, to poverty, crime and gender issues)."

If there is any hopeful edge to this story, it is that the sand crisis is not unsolvable. Best referred to a 2019 paper he co-authored for the journal Nature, one that included a so-called "agenda for sand." It entailed requiring sustainable sources of sand to be sought and certified, encouraging national and local governments to use alternatives to sand, reusing sand-based materials whenever possible and reducing the amount of concrete used in structures. The paper also called for multinational regulation of sand use, constant public education about the dangers of sand mining and a global monitoring program to assess when there have been ecological catastrophes related to sand mining.

"We have to take a holistic approach that centrally involves the stakeholders – those who lives are affected by sand mining (both positively and negatively) — and base our approach on the sustainable needs of communities, as well as the need to safeguard the environment to help mitigate harmful change," Best told Salon. "This demands approaches that are multidisciplinary and integrate the human and physical landscapes, to tackle the many issues of sand mining (across many different spatial scales – the issues of mining vary greatly between countries and continents), and how these issues will change in the coming decades as populations grow, technologies evolve and the demands for sand shifts spatially across the globe."

As Keiding put it, "The use of sand/aggregates is faced with two major challenges; one is related to the availability of high-quality resources addressed in my previous comments; the other is the environmental/climate impact of sand exploitation."

Read more

about mining:California’s Salton Sea eyed for lithium extraction with new tech

Facing shortages, chemists propose "mining" electronic waste for rare earth metals

By MATTHEW ROZSA is a staff writer at Salon. He received a Master's Degree in History from Rutgers-Newark in 2012 and was awarded a science journalism fellowship from the Metcalf Institute in 2022.