On Race, Time and Utopia

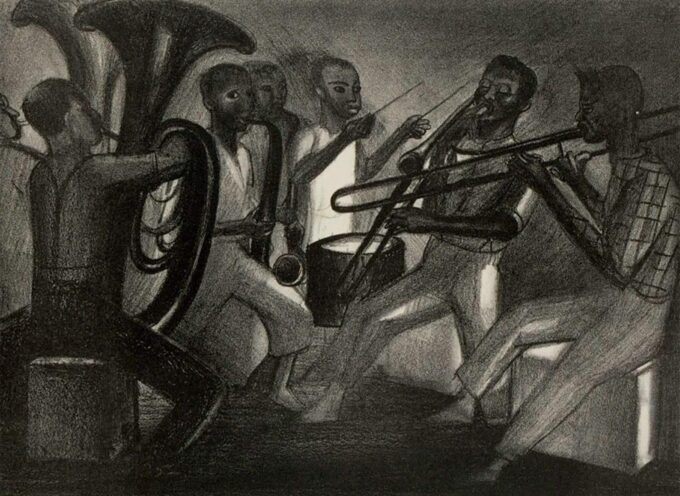

Image Source: Cover art for the book Race, Time, and Utopia: Critical Theory and the Process of Emancipation by William Paris

With his new book Race, Time, and Utopia: Critical Theory and the Process of Emancipation, philosopher William M. Paris makes an important contribution to several related conversations. Paris’s book offers one of the richest and most well-grounded recent accounts of utopia, firmly centering the question of class struggle and his distinctive understanding of race. The book is an attempt to reconstruct and interrogate “utopian tendencies that have been immanent in historical processes of emancipation from racial domination.” This is a multifaceted project that presents a new and exciting understanding of political and economic emancipation, drawing heavily on both the theorists of hope and utopia and the Black radical tradition generally.

Race, Time, and Utopia takes a new look at the utopian project and aims to clarify the relationship between our social practices as currently constituted and efforts to facilitate or frustrate “the ongoing task of full self-emancipation.” The book is a rare treat for those who seek out academic philosophy writing that is not boring. Paris’s prose is as clear and compelling as his philosophical claims. Some readers will recognize the author as one of the hosts of the popular podcast What’s Left of Philosophy. His students are a lucky group, and the book bears Paris’s characteristic ability to explain complex and layered arguments in a clear, straightforward, and engaging way.

Race, Time, and Utopia looks to philosopher Ernst Bloch (1885-1977) to help develop its conception of “new struggles of emancipation freed from ideologies that tend to naturalize our present form of life.” Bloch features prominently in the book, and gives it one of its key philosophical pillars in the idea of Ungleichzeitigkeit, which is discussed throughout as non-synchronicity or non-contemporaneity. Paris is very keen to develop the role of time in his picture of racial capitalism. The book makes a series of provocative claims about the relationship between time and the realities of racial domination. He says that time, and the sense of being out of step with it, are essential to the social experiences we associate with racism. Versions of this claim are woven into the arguments Paris presents throughout the book.

From the first pages, Paris is clear that he hopes to chart his own course, rejecting many of the assumptions we have come to associate with the discourses on racial justice, emancipation, and utopia. He sets out to challenge the notion of utopia as “an ideal that the philosopher introduces to social affairs,” instead urging that utopia is a concrete, “historical tendency that has shaped the world.” The philosopher doesn’t have to—and importantly shouldn’t—attempt to fashion utopia from whole cloth, but should find its elements in available stories of struggle and the recapture of certain spheres of temporal autonomy in the historical record. Paris believes that it is possible to discover the hints and characteristics of utopia as immanent aspects of historical dynamics. He is not interested in an account of utopia that builds it in the abstract and applies it to social reality from some hypothesized outside perspective. Paris is not advancing a vanguardism that imposes an intellectual’s vision of the perfect world from the outside.

He draws on Charles W. Mills (1951-2021) in his criticism of the dominant way of thinking about utopia, as an ideal introduced into the discourse by the philosopher. Mills argued that when we set up any model or ideal, we should begin with history and its injustices, rather than deliberately removing them from view. He gave an incisive critique of highly stylized models of the ideal that appeal to abstract principles, but do not account for deeply entrenched historical power relations. For Mills, the fashionable attempts at ideal theory were themselves deeply ideological; he writes, “Despite the long history of racial subordination of nonwhites (Native American expropriation, black slavery and Jim Crow, Mexican annexation, Chinese exclusion, Japanese internment), despite the long history of legal and civic restrictions on women, the polity is still thought of as essentially liberal-democratic.” This is part of the important work philosophers have often done to legitimate and naturalize the power of the ruling class. The philosopher, perhaps, can be forgiven for being out of touch with the realities of racial domination and class struggle. It comes with the territory of existing in the scholarly milieu. But for his part, Paris is sensitive to this distance between the real-world experience of the worker and the halls of academia, and he also introduces thinkers like James Boggs (1919-1993) in part to show the depth and complexity of ideas emerging from different contexts, outside of formal scholarship.

Paris follows Mills in taking much less for granted than most political philosophers, working in the close margins of an idealized world. For all of the high-flown rhetoric about rights, liberal-democratic political practice has ignored and thus naturalized some of the clearest historical examples of violent subordination. For as Mills wrote, “There could hardly be a greater and more clear-cut violation of property rights in U.S. history than Native American expropriation and African slavery.” This openness leads Paris to argue that we can find useful aspects of utopian consciousness in a broad range of movements and thinkers. While acknowledging shortcomings, Paris sees black nationalism as a source of relevant insights, particularly in its capacity to think beyond current social practices and posit new anchors for action and new ways of life.

But Paris sees the black nationalists as mistaken about the status of race, arguing that connecting the nation to race “risks reifying race as if it has a life of its own independent of our social practices rather than following from the organization of our social practices.” Paris believes that race is made-up, an emergent feature of our own conduct, not an “alien force” that controls us. Race is so deeply fixed in the social imagination that many have apparently come to accept it as real. As the book explains, because we live in racially unjust societies, we observe the fact that race has power in the world. But Paris says there are good reasons to worry about reifying race and imagining it as an aspect of social life that is situated beyond the reaches of our social practices. He draws from W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) in discussing “how a racist society tends to make it seem as if something called ‘race’ sorts different populations into hierarchical relationships rather than the practices and institutions of human beings.”

Professor Paris does not pull punches in his criticism of such “racial fetishism,” this perversion of being dominated socially by our own bad idea. He writes, “The inverted world of racial fetishism is one where history dominates the present and represses the utopian temporality of the ‘not-yet’ by reifying racial categories and relationships of domination.” Elevating race into this special position not only blinds us in the present, it limits the possibilities for the future. Here, Paris draws on Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), whose work describes a “descent into a real hell” that then opens the way to a fuller understanding of one’s place in the world. Fanon wrote, “There is a zone of nonbeing, an extraordinarily sterile and arid region, an utterly naked declivity where an authentic upheaval can be born.” Ernesto de Martino perhaps wrote similarly that those living in conditions of insecurity are always “exposed to the risk of a ‘crisis of presence.’” For Paris, this can be a space of utopian capacity and meaningful distance from the past. The book’s arguments connect the zone of nonbeing to Sartre’s nothingness, a state preceding the various social practices making claims on our bodies and our time. This state of nonbeing or nothingness may remind some of the work of German philosopher Max Stirner (1806–1856), whom Marx was famously at pains to dress down in The German Ideology.

Stirner was an existentialist forerunner who finds in his concept of “the unique” a “creative nothing,” a fundamental consciousness that cannot be reduced to the categories imposed on it. It is from this position of distance and creativity that we can take on utopian subjectivity. Paris contends that we can adopt this stance as a way to see the true character of our social practices and, as Marx says, the “muck of ages” more clearly. Racial fetishism, Paris argues, stands in the way of this Fanonian moment of transcendence from the vicious dehumanization of race. The stakes were clearly very high to Fanon: “The problem is important. I propose nothing short of the liberation of the man of color from himself.” Paris’s historical understanding of race situates it within a larger system of power and class, where race emerges as a mode of social behavior that legitimates an existing relationship of economic exploitation. Here, race is a secondary feature of a broader way of life, namely extractive class dynamics as within capitalism. It is this hateful context that creates race as a social anchor.

Paris argues that as long as our social order is defined “by actions that reproduce exploitation, scarcity, and hierarchy,” we cannot be surprised that the system produces results that treat certain groups “as surplus or disposable.” The fact of the relationship of power and extraction precedes and creates race; a certain group is made inferior because, as Fanon argues, a society that sustains itself through their exploitation has made them inferior by definition. The creation of race “mediates and legitimizes” their inferiority and thus follows as a matter of course. Racial fetishism brings about the incoherent and non-synchronous state in which the racialized individual must act as if race and its claims are true. Making a fetish of race serves to obscure class exploitation and hides the contingent, constructed character of economic hierarchies.

Given the role racial fetishism plays within the exploitative capitalist system, Paris follows Fanon in arguing that we cannot address it merely by thinking differently about any given group of people. Instead we must be ready to address and overturn the social and economic foundations of race and racial fetishism. For Fanon, “effective disalienation” requires both recognition of the role of the economic system and the “internalization—or, better, the epidermalization—of this inferiority” within the system. Confronting race before the deeper question of its role within the social and economic paradigm puts the cart before the horse: it tries to treat race as if it truly has a separate reality, ignoring its embeddedness in overlapping social, political, and economic hierarchies. Paris believes that racial fetishism of this kind is also present in more progressive political circles, and he argues forcefully for an approach that draws more attention to history and class relations. In reality, that is, historically, categories of race were not real or readily apparent on their own, but were codified specifically to justify and stabilize a coerced workforce. Those who fetishize race, putting it in the position of first importance, share the same position as those who want to perpetuate it.

Paris argues that because racial fetishism “continues to entrap social forms of consciousness,” we have not been able to address deeper questions about our society. He calls upon Fanon’s argument that even reparations serve a role of solidifying racial categories and roles. He thinks that one of the reasons we continue to recreate the social practices of race is because we have so mystified it: we “mystify these past practices as natural rather than artificial and thus frame the interrogation of our freedom and social practices as questions of essence or authenticity rather than invention.” Moving beyond the fetishization of race permits humanity to occupy the central position in how we organize our time and anchor our social practices. Race, Time, and Utopia is not hesitant to enter a contested territory among those on the political left. The left has been keen to debate on the relationship between race and class and the relative prominence of each as a factor in social relations. Paris notes at the book’s outset that his focus is not racial justice as construed by the mainstream of political philosophy. He wants us to zoom out and see the place of race in a much larger social and economic system. But his explanation of race is made even more nuanced and compelling by positioning it within a framework of class dynamics. And within the context of the economic system and its class structure, race has always been about time and a ruling class’s control over certain people’s time. The book argues that “racial domination is at bottom the domination of time by one group over another.” Beyond the control over a certain group’s time, racial domination also involves making that group permanently out of sync socially. There is a non-contemporaneity to racist societies that manifests in several ways. For example, it is easy to see that formal rights do not guarantee freedom from racial domination. Our society is incoherent in that it regards itself as one thing, but is another. This is a form of temporal friction or discordance, and it is imposed on Black people to put them at odds with the rhythm of mainstream life. Among Paris’s unique contributions with the book is this conception of temporality, his understanding of racial capitalism as essentially a series of impositions on the time of a certain group. For Paris, time is crucially important. It is the medium through which racial domination takes shape and comes to be a coherent social practice.

He provides a reading of Du Bois through the lens of the allegory of the cave, from Plato’s Republic. In this reading, Black people are “trapped in a world of appearances, cut off from one another, and ruled by those who do not have their best interests at heart.” While Paris is disinclined to accept Du Bois’s elitism and vanguardism, he is interested in the social ontology underlying Du Bois’s arguments. Du Bois’s characterization suggests that slavery set Black people off on a different track, a “different historical and cultural rhythm than the rest of society.” The color line keeps them in a condition of “non-synchronous domination,” where they are never truly in accord with the modern social order. This plays out both in the special differentiation imposed by segregation and in a temporal rift created by social practices that orient themselves around very different expectations.

Because the social practices of the present give rise to such discordance, utopian consciousness persistently “generates a sense of untimeliness,” according to Paris. It seems to want too much too soon, or else it seems to miss its opening. He argues that we are now often in states of crisis consciousness, as distinct from class consciousness. Moments of crisis, when the habits and expectations of daily life have been dramatically disrupted, can produce moments of questioning that challenge structures of power and domination (he points to the example of the protests after the murder of George Floyd, during the Covid pandemic). The challenge is to synchronize such moments of crisis consciousness with genuine, sustainable utopian consciousness.

In his book, Paris suggests “the existence of a truer society from within the false society of racial domination,” following Du Bois in calling it “the kingdom of culture.” Our society remains “temporally out of joint,” but inspired work like Race, Time, and Utopia gives us new ways to think about how we could make it more free, just, and coherent. One of the benefits of reading philosophers who do engage with history, with what actually happened, is that their social ontologies are based in something more than pure theory. Paris does not diminish the importance of racism in the story by placing it within its economic context. In addition to the seminal figures discussed in the book, many readers will be reminded also of consonant work by Gerald Horne and Cedric Robinson, among many others. Horne and Robinson come to mind because they were, in their own ways, deeply critical of theorizing either race or class by isolating them from their deep historical entanglement. Within that framework, they saw race as centrally important, as constitutive of capitalism and part of its foundations. Placing racism within an explanation of class dynamics only clarifies our picture of both, and Paris carries on this conversation here in the world of philosophy. The result is an approach that makes meaningful headway against the false choices and unchallenged premises of the prevailing conversations on race and political emancipation.

Race, Time, and Utopia reveals a thinker who, like Fanon, is committed to always questioning, who from the radically open place of the zone of nonbeing, can genuinely hear the reasons and justifications of others. This is the truly utopian spirit, but expressed with subtlety and seriousness. In concluding the book, Paris discusses strategies for loosening the hold of the present on our social imagination. This is where the non-synchronicity he discusses throughout the book can be reframed as a point of departure for full self-awareness and utopian consciousness. We can visit a new temporal space where we have the ability to think differently about the future, to imagine it in new ways.