By Mark Hammond

12.11.2025

TRIBUNE

While psychotherapy is often viewed as an exclusive, individualistic preserve, it also incorporates a strong element of social critique — and its modern history contains startling examples of therapy rooted in radical democratic principles.

While psychotherapy is often viewed as an exclusive, individualistic preserve, it also incorporates a strong element of social critique — and its modern history contains startling examples of therapy rooted in radical democratic principles.

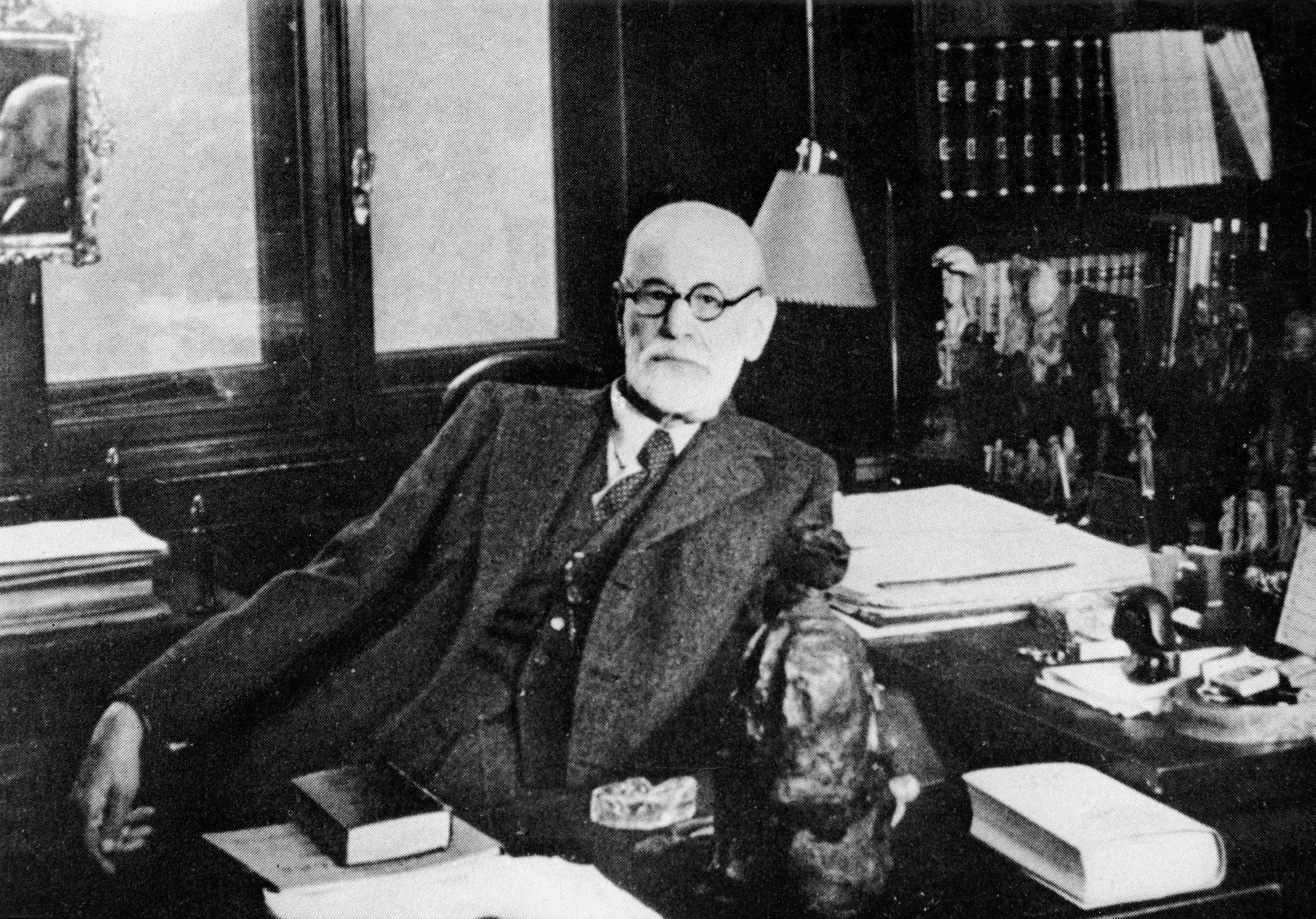

Portrait of Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud (1856 - 1939) as he sits behind his desk in his study, Vienna, Austria, 1930s. (Credit: Authenticated News via Getty Images.)

If I were to ask you to free-associate on the term ‘psychotherapy’, you might not make it beyond a miasma of imagined jargon. Perhaps, for some of you, the term conjures images of philodendrons dangling from bookshelves lined with titles such as Atomic Habits. You might imagine jute rugs bathed in soft light pinned under a coffee table, upon which sits a box of tissues, invoking the solemnity of a votive.

All of which is to say that in the popular conception of psychotherapy, everything is contained in one, private room. It would be fair to say that psychotherapy is largely regarded as a private service for individuals to lay out all manner of experiences, so that they can explore their personal inner tumult.

However, looked at another way, we can see how, in fact, these experiences are substantially social in nature, and that psychotherapy is, in some ways, a reduction of these social experiences to personal events in the psyche. This all serves to illustrate the multitudes of the form — primarily the individual, private position of the client, but also the wider socio-political slant that cannot help but inform their life.

If one traces a line back to the Enlightenment, from thinkers like Descartes up to Freud, and through various paradigms like Behaviourism and modern-day Relational approaches, one can see how the private has become more and more interconnected with the social and the political in psychoanalytical models. Descartes placed human experience inside the vacuum of individual interiority; I think, therefore I am. Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard developed ideas about an ethical stage via his ‘stages of becoming’, wherein the individual progresses to a way of life in step with societal expectations (and the existential struggle of adapting to these expectations).

Though Freud’s is primarily a psychology of constitutional factors such as sexual desires and drives, as early as 1908, in ‘“Civilized” Sexual Morality and Modern Nervous Illness’, he considered the socio-political factors of repressive societal demands, and the psychological effects upon the individual. While Freud developed his theories, Structuralists like Ferdinand de Saussure challenged Cartesian assertions about the individual, proposing that one cannot simply extract the individual from their environment in order to understand them.

I work in a primary school (not just with young children, but also with private clients, whose ages range from the teens up to the fifties and beyond). Having trained with a specialism in child psychotherapy, I learned early on of developmental theories, such as the Attachment Theory of Ainsworth and Bowlby, and Bandura’s Learning Theory. Underpinning these theories are the interactions between biology and the environment — the intrinsic and extrinsic, development as a social process: a process of becoming through a matrix of relationships, to others and to the environment.

In the 1960s, English Psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion developed his ideas around containment. This is a process imperative to the child’s primary caregiver, but also to the therapist — and it returns us to the containment of the solitary therapeutic room, which, along with the therapist, is itself a container for the client and their feelings, thoughts, and emotions. The primary challenge I find in psychotherapeutic work is in this sense of containment.

While I can offer up myself and this private room as a receptacle for the client, in order to help to ‘transform’ intolerable psychic material (as it were), the client will of course leave this containment once our fifty minutes is up, and return to the many other containing spaces that constitute the social framework of life. That is to say, I might very well sit with a client in a private space and receive their most painful projections — and if things go extremely well I might assist in helping the client to re-process and integrate these feelings and emotions. But they still have to go home afterwards, potentially to a household where trauma and abuse are prevalent, or at the very least go back out into a world built upon the cold steel transoms and ledgers of capitalism.

My work in schools makes the political very much tangible and makes it clear that psychotherapy is battened to the socio-political. In 2017, a national policy was published called ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision’. The paper addressed what I am only too familiar with: the lack of accessibility to mental health services for children and young people; inequalities that help to create mental health issues, which are then perpetuated by other mental health issues; waiting lists for services such as CAMHS being incredibly long, and, as in the case of my school, staff who are overworked and often under-appreciated.

Griffin et al., (2022) analyse this paper and consider how policies are often tantamount to ‘political interventions’, serving to justify and embed certain healthcare ‘pathways’ as a means to an end of justifying a political agenda. For instance, early intervention sounds almost commonsensical when you think of it as a set of programmes to help children to improve their lives at a crucial point in their physical, cognitive, and emotional development. However, it has been argued that such policies lay blame at the feet of the parents rather than the social forces that help to create inequality in the first place. ‘Rather than undermining neoliberal philosophy, social investment approaches sustained and intensified it’, as Gillies et al., (2017) assert.

Looking back over the modern history of psychotherapy will be helpful at this point. There may not have been the exact same concerns back in the 1950s, when Eric Berne — the founder of the Transactional Analysis (TA) method of psychotherapy, and a key influence on my own practice — was writing. But Berne was driven by an ethos of equality, and a desire to make therapy accessible to all.

So why did Berne distance his method from the political, at least outwardly? Claude Steiner, a French-born psychologist, was a friend of Berne’s, and collaborated with him in the development of his theories. In 2010, Steiner wrote of his lifelong assumption that Berne was avowedly apolitical (Steiner himself had studied physics at Berkeley, but made a decision ‘not to make bombs’ and transferred to the study of child development). Berne passed away in 1970, but it wasn’t until 2004 that it was revealed to Steiner through Berne’s son, Terry, that Berne had been investigated by the House of Representatives’ Select Committee on Un-American Activities. Steiner mentions the ‘severe persecution’ Berne was subjected to as he was interrogated, and how Berne lost his government job and had his passport rescinded. What had Berne done? In 1952, he had signed a petition that questioned the treatment of leftist scientists in government.

The nuances of Berne’s narrative cast a long shadow. While authoritative cultural voices today persist in placing the burden on the individual, I spend a good deal of my time worried that I am enabling the continuation of the status quo by helping clients to simply endure their lot. Capitalism induces anxiety in us and then demands that we privately do something about it, as if health is not even slightly socially-determined. This is ‘deliberately induced to block political action’ (Frosh, 2017).

Then I remember the tenets of TA. That Berne sought to strip away hierarchies of power, starting at an interpersonal level. Berne advocated for an accessible therapy for all, free of isolating vernacular and the power-dynamic of the almighty therapist/healer. Berne was anti-elitist and proposed that we all had the ability, through analysis of our communication, to clear the way through game playing into intimacy, and an undertaking of a ‘redecision’ about who we are and how we relate to the world. Via Ego States, he revealed how we not only internalise parental messages but how dominant forces in the world exact their parental force on us. TA shows us that we have the personal potency to change how we engage with this world and from which private position we do so (how we are affected by the world and how we wish to affect the world).

Berne understandably distanced himself from politics during the Red Scare, but there is much for us to take from his commitment to continuing his work regardless, and developing a sociopolitical theory rooted in democratic principles — all despite this very real fear of reprisal from oppressive, authoritative voices seeking to discount his very existence. As we seek to understand the complex interplay between the individual and the social in contemporary psychotherapy, we could do a lot worse than heed his example.

Contributor

Mark Hammond is a Psychotherapist from Gateshead and the author of Victims, Aren't We All?

No comments:

Post a Comment