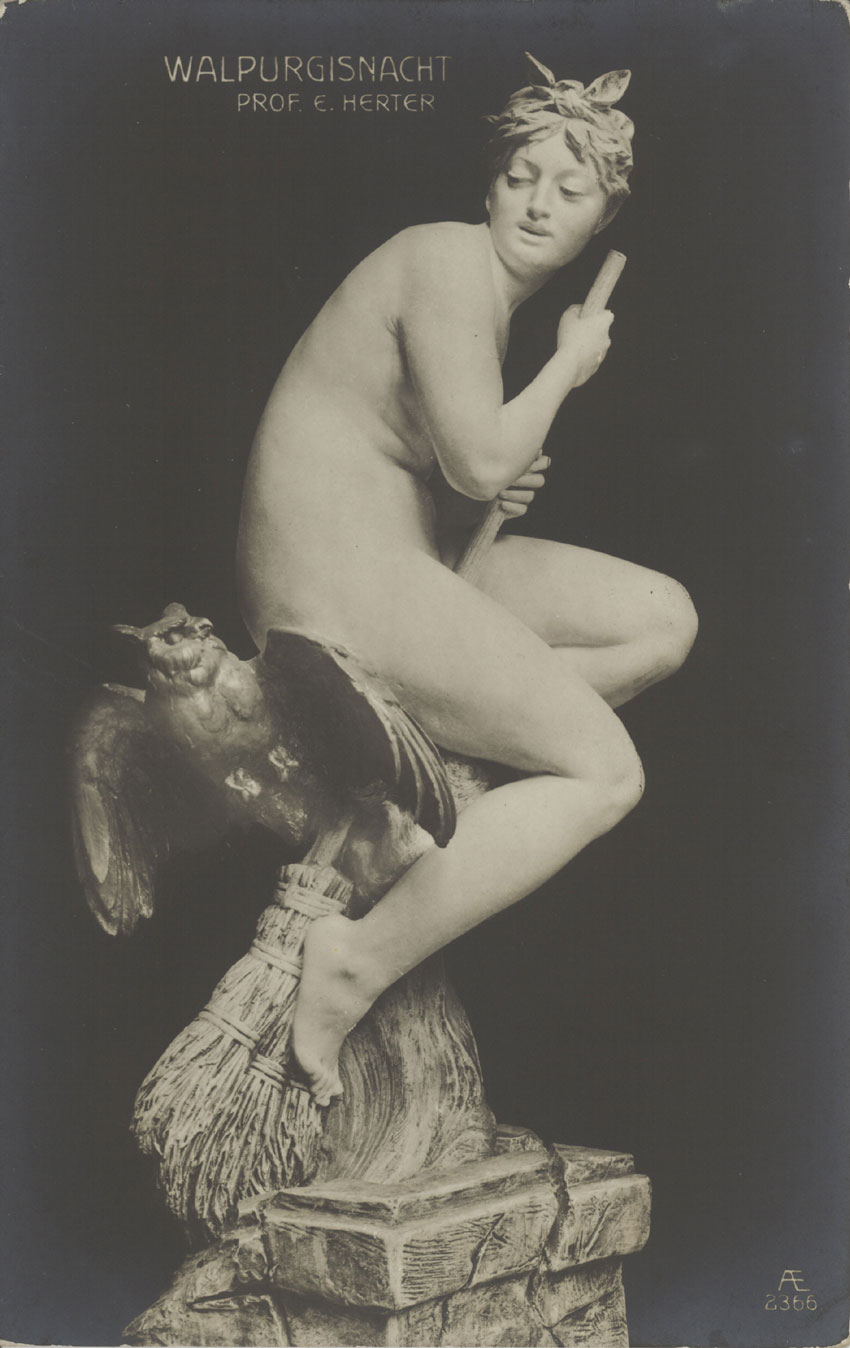

There is something sinister about the Canadian Tax system. It is declared that we must file taxes by Midnight April 30. This is Walpurgisnacht, or night of the witches, the ancient pagan festival of fire; Beltane, and consumption of the last of the salted meat from harvest in celebration of the new life of spring.

Death and Taxes as they say. Leads to rebirth new life.

Walpurgisnacht,night of the witches the celebration of the end of darkness and the fire rituals of spring. We pays our taxes and hopes we gets some back from the tax man. A sacrifice, even if it is in coin, as the season demands.

Goethe and Mendelssohn express this Euroean pagan tradition in verse and song.

Mendelssohn's Choral arrangement is a modernist paenan to paganism. But damn we still must give unto Caesar; the real meaning of the festival of fools........

Mendelssohn’s Walpurgisnacht

Conductor : Valérie Fayet

Walpurgis Night, based on a work by Goethe, celebrates the popular tradition which talks about pagan gatherings taking place on the “witches' mountain” during the night of May 1 st.

Mendelssohn's work is admirably clear, colourful and full of energy.

Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, cantata for chorus & orchestra, Op. 60 So weit gebracht, daß wir bei Nacht

Die erste Walpurgisnacht Op. 60: So weit gebracht, dass wir bei Nacht Listen

Composed by Felix Mendelssohn

Performed by Chamber Orchestra Europe

Conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt

A period of travel and concert-giving introduced Mendelssohn to England, Scotland (1829) and Italy (1830-31); after return visits to Paris (1831) and London (1832, 1833) he took up a conducting post at Düsseldorf (1833-5), concentrating on Handel's oratorios. Among the chief products of this time were The Hebrides (first performed in London, 1832), the g Minor Piano Concerto, Die erste Walpurgisnacht, the Italian Symphony (1833, London)

SEE

5. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: Ouverture: 1. Das schlechte 2. Der Ubergang zum Fruhling -

6. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: I Es lacht der Mai! -

7. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: II Konnt ihr so verwegen handeln? -

8. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: III Wer Opfer heut' zu bringen scheut -

9. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: IV Verteilt euch hier -

10. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: V Diese dumpfen Pfaffenchristen - Kommt mit Zacken und mit Gabeln -

11. Die Erste Walpurgisnacht, Op. 60: VII So weit gebracht - VIII Hilf, ach hilf mir, Kriegsgeselle - IX Die Flamme reinigt sich vom Rauch -

O+1+2.nwc: 0: Overture : 1: Now may again : 2: Know ye not a deed so daring? 3+4.nwc : 3: The man who flies : 4: Disperse, ye gallant men 5+6+7+8+9.nwc: 5: Should our Christian foes assail us : 6: Come with torches brightly flashing : 7: Restrain'd by might : 8: Help, my comrades : 9: Unclouded now, the flame is bright

"...don't you think this could become a new kind of cantata?" Rituality, Authenticity and Staging in Mendelssohn’s Walpurgisnacht

Assuming a potential analogy between art and ritual, or between art and the interpretation of ritual as a Gesamtkunstwerk, the question arises as to what degree boundaries or transitions between aesthetic presentation, staging and identification with ritual can be determined in art. This topic could be discussed in terms of reception-aesthetics, with the question of the participation of an implicit or exclusive audience in ritual or in art. On the other hand, the perspective of this question can also be developed, as in this article, in terms of production-aesthetics, using the model of a musical composition based on a preexisting literary text. In Goethe's and Mendelssohn's texts,' not only their cultic-religious rituality will be investigated, but also the problem of how far beyond the cultic subject the immanent formative principles of ritual in terms of music are effective. Although in his early ballad Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night) of 1799 Goethe distinguished the pagan Walpurgis night from the classical and romantic in both stages of Faust, in his own way Mendelssohn related these three forms of ritual directly to one another within one work.Cantata - LoveToKnow 1911

In modern times the term cantata is applied almost exclusively to choral, as distinguished from solo vocal music. There has, perhaps, been only one kind of cantata since Bach which can be recognized as an art form and not as a mere title for works otherwise impossible to classify. It is just possible to recognize as a distinct artistic type that kind of early r9th-century cantata in which the chorus is the vehicle for music more lyric and songlike than the oratorio style, though at the same time not exclude ing the possibility of a brilliant climax in the shape of a light order of fugue. Beethoven's Glorreiche Augenblick is a brilliant "pot-boiler" in this style; Weber's Jubel Cantata is a typical specimen, and Mendelssohn's Walpurgisnacht is the classic.

The Jews seem fated to wanDer forever among other nations and be faced perpetually with minority status and a legitimate pressure to acculturate and assimilate. If one compares the ending of The Eternal Road to Felix Mendelssohn's setting of Goethe's Die erste Walpurgisnacht, one is struck by a vital difference. Mendelssohn, although bearing the most celebrated name in early nineteenth-century German-Jewish history, had been converted and become a devout Protestant. Nevertheless through his music he celebrated with empathy and pride the courageous resistance of the Druids to the siege on their traditions and beliefs laid by violent Christian attackers. In contrast, The Eternal Road ends much more ambiguously with a vague hope for a return to Zion among a defeated and divided community, bowing to a fate of perpetual exclusion, persecution, and powerlessness.

Mendelssohn, Goethe, and the Walpurgis Night

The Heathen Muse in European Culture, 1700-1850

John Michael Cooper

Mendelssohn, Goethe, and the Walpurgis Night is a book about tolerance and acceptance in the face of cultural, political, and religious strife. Its point of departure is the Walpurgis Night. The Night, also known as Beltane or May Eve, was supposedly an annual witches' Sabbath that centered around the Brocken, the highest peak of the Harz Mountains.

After exploring how a notoriously pagan celebration came to be named after the Christian missionary St. Walpurgis (ca. 710-79), John Michael Cooper discusses the Night's treatments in several closely interwoven works by Goethe and Mendelssohn. His book situates those works in their immediate personal and professional contexts, as well as among treatments by a wide array of other artists, philosophers, and political thinkers, including Voltaire, Lessing, Shelley, Heine, Delacroix, and Berlioz.

In an age of decisive political and religious conflict, Walpurgis Night became a heathen muse: a source of spiritual inspiration that was neither specifically Christian, nor Jewish, nor Muslim. And Mendelssohn's and Goethe's engagements with it offer new insights into its role in European cultural history, as well as into issues of political, religious, and social identity -- and the relations between cultural groups -- in today's world.

Among some of his (Goethe’s) most engaging/compelling musical experiences of his late maturity were the visits of Felix Mendelssohn, who was 12 years old in 1821 and had been introduced to Goethe personally in Weimar by his (Mendelssohn’s) teacher, Zelter. Further visits took place in 1822, 1825, and 1830. Goethe had Mendelssohn play for him and explain to him technical matters concerning music and music history. This relationship became one of tender devotion on the part of Goethe towards Mendelssohn: in 1822 Goethe said to Mendelssohn: “I am Saul and you are my David,” and in his last letter to Mendelssohn, Goethe began with “My dear son.” Mendelssohn dedicated his Piano Quartet in B minor, opus 3 to Goethe and composed music for “Die erste Walpurgisnacht” (1st version in 1832)…. Goethe was eager to hear instrumental music which was played by Reichardt, Kayser, Zelter, Eberwein, Hummel, Spohr, Beethoven, Baron Oliva, Szymanowska (female pianist), J. H. F. Schütz, and finally by Mendelssohn whom he repeatedly asked to play something for him.”]

Mendelssohn's Die erste Walpurgisnacht, one of his greatest cantatas, was based on Goethe's Faust, and on Goethe's personal interpretation of the scene (Grove Dictionary 146). Mendelssohn's friendship with the poet lasted for a great many years, up until Goethe's death in 1832.The first Walpurgisnacht

The Ouverture represents the transition from the winter to spring. The beginning in A-Moll is overwritten with “the bad weather”, while with the idiom into the Dur variant approaching the Walpurgisnacht in spring is announced. It is described in the following, as the priests and Druiden of the Celts meet secretly in the inhospitable mountains of the resin, in order to address after old custom with fire their prayer to the all father of the sky and the earth. Since their rites are forbidden by the Christian gentlemen however, everything must happen in the secret one. With cheat and to linings the soldiers of the Christians were frightened in such a manner that the Celts in peace can celebrate their Walpurgisnacht.

There are two Walpurgisnächte in Goethe's work. Admits is above all that from that fist I, in which a typical Hexensabbat is sworn to in visionär grotesque way. On the other hand Goethe takes poem the first Walpurgisnacht a heidnisches victim celebration developed to 1799 in that during thunderstorm eight to the cause to confront two incompatible ways of thinking and being LV each other.

Whole 19. Through century the romantic composers let themselves fist be inspired again and again from the picture world of the I and fist II, while the first Walpurgisnacht remained almost unknown. Only Carl Friedrich Zelter, Goethe friend and musical advisor, have try, the poem tone. It kept full fifteen years it under its papers, before it took distance finally from a project, which exceeded its imagination.

That was introduced by Zelter at that time twelve-year-old boy Mendelssohn with around sixty years the older Olympier Goethe, whom time and fame had coined/shaped. By Beethoven and Schubert to judge, understood the old gentleman not much about music. In its youth he had heard some of the Mozarts' works, whose clarity and harmony it zollte still at the age attention and acknowledgment; and it found favours to feel with the citizen of Berlin miracle child from good family the aftereffect of those melodies in those the ideal of its own youth lived. It would be inaccurate to speak of a co-operation between Goethe and Mendelssohn. The first important piece, to which the poet energized the young musician, was the Ouvertüre sea silence and lucky travel, which arrived only in the year 1832, Goethe's death year, at the public performance. That Goethe would have known to appreciate a music, so clearly under Beethovens the influence is to be doubted. Just as little it the score of the first Walpurgisnacht would have probably behagt. The work, in which orchestras and voices verwoben closely into one another are, becomes not completely fair the central thought of the artist Philosphen. From its “Faible for witches” seduced, Mendelssohn stated little interest in the deeper meaning of the poem: the always-lasting conflict between the instinktiven natural forces on the one hand and the mental clarity of a thought world coined/shaped by the clearing-up on the other hand. With the primarily romantic treatment of the article it remains on the level of a descriptive poem and tears us in tumbles uncontrolled thunderstorm eight.

The 1831 completed first minute of the score experienced substantial changes, before she arrived to 1842 at the premiere. Goethe did not experience no more, which regulation to his verses assign became, whose Vertonung lends a fascinating juvenile fire to them. Mendelssohn proves here as genuine romantics. It uses a pallet of magnificent tone qualities, lets the horns from the supple fabric of the Streicher step out and gives to the Holzbläsern a most personal note. The choirs are from a Schlichtheit, which lends occasionally the serious character of a Volksliedes to them, while proper large airs are assigned to the soloist.

The whole wealth of the romantic opera is united in this musical illustration of a poem, which reminds at the Feenzauber of shakespearscher scenes. The choir of the Druiden (No. 6 of the score) is from an imaginativeness, which only the late Verdi in the last act of its Falstaff reaches again. The composer, at whom Goethe estimated the causing its own youth, somehow not completely up-to-date one, appears here surprisingly as one of the prophets of the music 19. Century. With deciveness it secures the transition from Beethoven to the large rhapsodies of Brahms.Jean Francois Labie

(Translation: Ingrid trusting man)G O E T H E ' S P A G A N P O E T R Y

Goethe, a genius with unmistakable Pagan sympathies,

excelled as a poet, dramatist, novelist, essayist,

philosopher and scientist (his works occupy 140

volumes!). Here are several of his Pagan poems,

including his ballade "The First Walpurgis-Night," in

which the Pagans score a Discordian victory over their

oppressors. (I'm sure Goethe now dwells happily among

the Pagan Gods.) The ballade has been set to music by

Mendelssohn (Die Erste Walpurgisnacht), which is quite

good, but not suitable for small group performance.

Perhaps the Muses will help some modern Pagan to

compose a version for contemporary witches' sabbats.

Although only the God (Allvater) is mentioned, I've

left Goethe's text unchanged; it's easy to substitute

"Mother" for some or all of the "Father"s if you like.

-- John Opsopaus

THE FIRST WALPURGIS-NIGHT

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

A DRUID.

Sweet smiles the May!

The forest gay

From frost and ice is freed;

No snow is found,

Glad songs resound

Across the verdant mead.

Upon the height

The snow lies light,

Yet thither now we go,

There to extol our Father's name,

Whom we for ages know.

Amid the smoke shall gleam the flame;

Thus pure the heart will grow.

THE DRUIDS.

Amid the smoke shall gleam the flame;

Extol we now our Father's name,

Whom we for ages know!

Up, up, then, let us go!

ONE OF THE PEOPLE.

Would ye, then, so rashly act?

Would ye instant death attract?

Know ye not the cruel threats

Of the victors we obey?

Round about are placed their nets

In the sinful Heathen's way.

Ah! upon the lofty wall

Wife and children slaughter they;

And we all

Hasten to a certain fall.

CHORUS OF WOMEN.

Ay, upon the camp's high wall

All our children loved they slay.

Ah, what cruel victors they!

And we all

Hasten to a certain fall.

A DRUID.

Who fears to-day

His rites to pay,

Deserves his chains to wear.

The forest's free!

This wood take we,

And straight a pile prepare!

Yet in the wood

To stay 'tis good

By day till all is still,

With watchers all around us placed

Protecting you from ill.

With courage fresh, then, let us haste

Our duties to fulfil.

CHORUS OF WATCHERS.

Ye valiant watchers now divide

Your numbers through the forest wide,

And see that all is still,

While they their rites fulfil.

A WATCHER.

Let us in a cunning wise,

Yon dull Christian priests surprise!

With the devil of their talk

We'll those very priests confound.

Come with prong and come with fork,

Raise a wild and rattling sound

Through the livelong night, and prowl

All the rocky passes round.

Screech-owl, owl,

Join in chorus with our howl!

CHORUS OF WATCHERS.

Come with prong, and come with fork,

Like the devil of their talk,

And with wildly rattling sound,

Prowl the desert rocks around!

Screech owl, owl,

Join in chorus with our howl!

A DRUID.

This far 'tis right,

That we by night

Our Father's praises sing;

Yet when 'tis day,

To Thee we may

A heart unsullied bring.

'Tis true that now,

And often, Thou

Favorest the foe in fight.

As from the smoke is freed the blaze,

So let our faith burn bright!

And if they crush our olden ways,

Who e'er can crush Thy light?

A CHRISTIAN WATCHER.

Comrades, quick! your aid afford!

All the brood of hell's abroad:

See how their enchanted forms

Through and through with flames are glowing!

Dragon-women, men-wolf swarms,

On in quick succession going!

Let us, let us haste to fly!

Wilder yet the sounds are growing,

And the arch fiend roars on high;

From the ground

Hellish vapors rise around.

CHORUS OF CHRISTIAN WATCHERS.

Terrible enchanted forms,

Dragon-women, men-wolf swarms!

Wilder yet the sounds are growing!

See, the arch fiend comes, all-glowing!

From the ground

Hellish vapors rise around.

CHORUS OF DRUIDS

As from the smoke is freed the blaze,

So let our faith burn bright!

And if they crush our olden ways,

Whoe'er can crush Thy light?

[Bowring translation]

THE CONSECRATED SPOT

When in the dance of the Nymphs, in the

moonlight so holy assembled,

Mingle the Graces, down from Olympus in secret

descending,

Here doth the minstrel hide, and list to their

numbers enthralling,

Here doth he watch their silent dances'

mysterious measure.

[tr. Bowring]

[All selections from "The Poems of Goethe," New York:

John D. Williams, 1882.]

finisThe Romantic Mendelssohn: The Composition of Die erste Walpurgisnacht

JSTOR: The Music of To-Day

THE FAUST LEGEND IN MUSIC

Paganism

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

Fire, choral music, Gnostic, Druids, Spring, Germany, Carnival,Mendelssohn, pagan, Divine Fool, Faust, Tree of Life, Christianity, Walpurgisnacht, Beltane, Goethe, magick, gnostic