The most sacred text that will be sung, read and celebrated this week of Passover is the Song of Songs, originating from love songs of the ancient Egyptians handed down through the Canaanite peoples, whom were both Jews and Palestinians.

The most sacred text that will be sung, read and celebrated this week of Passover is the Song of Songs, originating from love songs of the ancient Egyptians handed down through the Canaanite peoples, whom were both Jews and Palestinians.

And it is a text celebrated by all Abrahamic religions; Jews, Muslims and Christians. Ironically it is a profane text, one that makes no direct reference to God. It is a love poem a pagan paean to Eros not Agape.

The Song of Songs, the Song of Solomon, the Shir HaShirim, the Holy of Holies, the Canticle of Solomon, all its various names is one of the shortest texts in the Old Testament, but one pregnant with Qabbalistic , Gnostic and occult meaning.

I have studied this text for thirty years. And I consider it the meme of all Western Occultism.

The core meme of Western Occultism is the lost knowledge (gnosis) of mankind. That there was a Golden Age of Knowledge, from the Greek tradition, lost Atlantis, etc. are all memes of some lost or forgotten knowledge. That Gnosis is actually there in front of everyone, for the blind to see. It is the Song of Songs in the Old Testament.

It is a profane poem in an otherwise holy book. And those who defended it called it the Holy of Holies. This contradiction has fascinated me for years as a ceremonial magickian and historian of religion. And with these insights, or at least starting points I have came to the realization that the Song of Solomon, the Canticles, the Holy of Holies, the Song of Songs, all its titles is the most sacred text in Western philosophy. It is heresy itself, hidden in plain site, in the holiest texts of all Abrahamic based religion. It is also the sacred wisdom attempted to be rediscovered by the Rosicrucian's and the Freemasons.

The core of Western Occultism, magick, and Rosicrucianism is that there is some lost secret, lost wisdom, and there is some lost civilization that held this knowledge. The lost book, the secret grimore, the Gnosis of God, was hidden in plain site, it was never lost. It is the Song of Songs; a profane erotic love poem.

While there is a wedding celebration at the center of the Song (5:1), the elements of movement in the royal and pastoral milieu suggest a narrative more complex and developed than a mere wedding song-cycle.

movement in the royal and pastoral milieu suggest a narrative more complex and developed than a mere wedding song-cycle.

With the release of Marvin Pope's massive Anchor Bible commentary on the Song (Song of Songs, Doubleday, 1977), a rather perverse view of the book has been advanced. Pope regards the book as a liturgy from a fertility cult ritual or funeral feast, i.e., the sacred marriage to the gods reenacted cultically. He provides a plethora of obscene poems and pornographic graffiti from the Ancient Near East in support of this dubious thesis. In truth, one learns more about Professor Pope's fantasies than about the content of Solomon's inspired Song.

The final views of the book are variations on a theme. Most modern scholars now regard the book as a love poem expressive of the passion between a man and a woman. Some regard the two lovers as Solomon and his Shulammite; others regard the names in the book as "idealized." The other view of the work as a love poem regards it as a collage or compilation of numerous love lyrics arising from numerous settings. The difficulty with this latter view is that the unity of the Canticle depends on a very skillful redactor or editor. Why not the skill of a single author?!!

No religious apologetics or deliberate misinterpretations of it can change this fact. As one Biblical Blogger wrote;

(As an aside, I have often been puzzled by more conservative scholars who argue for Solomonic authorship of the Song and maintain that it is a celebration of human erotic love within the context of a monogamous marriage relationship. Was not Solomon known for his many wives and concubines (1Kings 11)? I don’t see how he could be held up as a modern paragon of love and faithfulness)

It is clear that this is one of the earliest magickal incantations and exorcsims of death. As the Egyptians suffer the tenth plague, the Angel of Death, itself an androgynous figure not unlike Lucifer, is only thwarted by a marriage incantation, a lover's poem of devotion. This banishing, itself another form of androgyny, the commingling of the male and female into one, is the secret key of all later Gnosticism, Rosicrucianism and magick. It is Eros versus Thantos.

Just as it is both a poem and a dramatic ritual, it is also a magickal ritual of invocation, evocation and banishment. It is overlooked as such by the sensationalism of the lambs blood x on the doors, or the sacred meal and Sedar celebrations. These are the stage settings, the real ritual is the reading of the Song of Songs.

The Song is a celebration of love, eros, sexuality, and fecundity. It is both a drama between two lovers, it is also a collective celebration in that the Daughters of Zion, are actually Palestinian peasant women celebrating the harvest. There is a dialog and there is a dramatic personae in the background. A story within a story. And that story is related to the Qabbala. I go into some detailed explanations of this below.

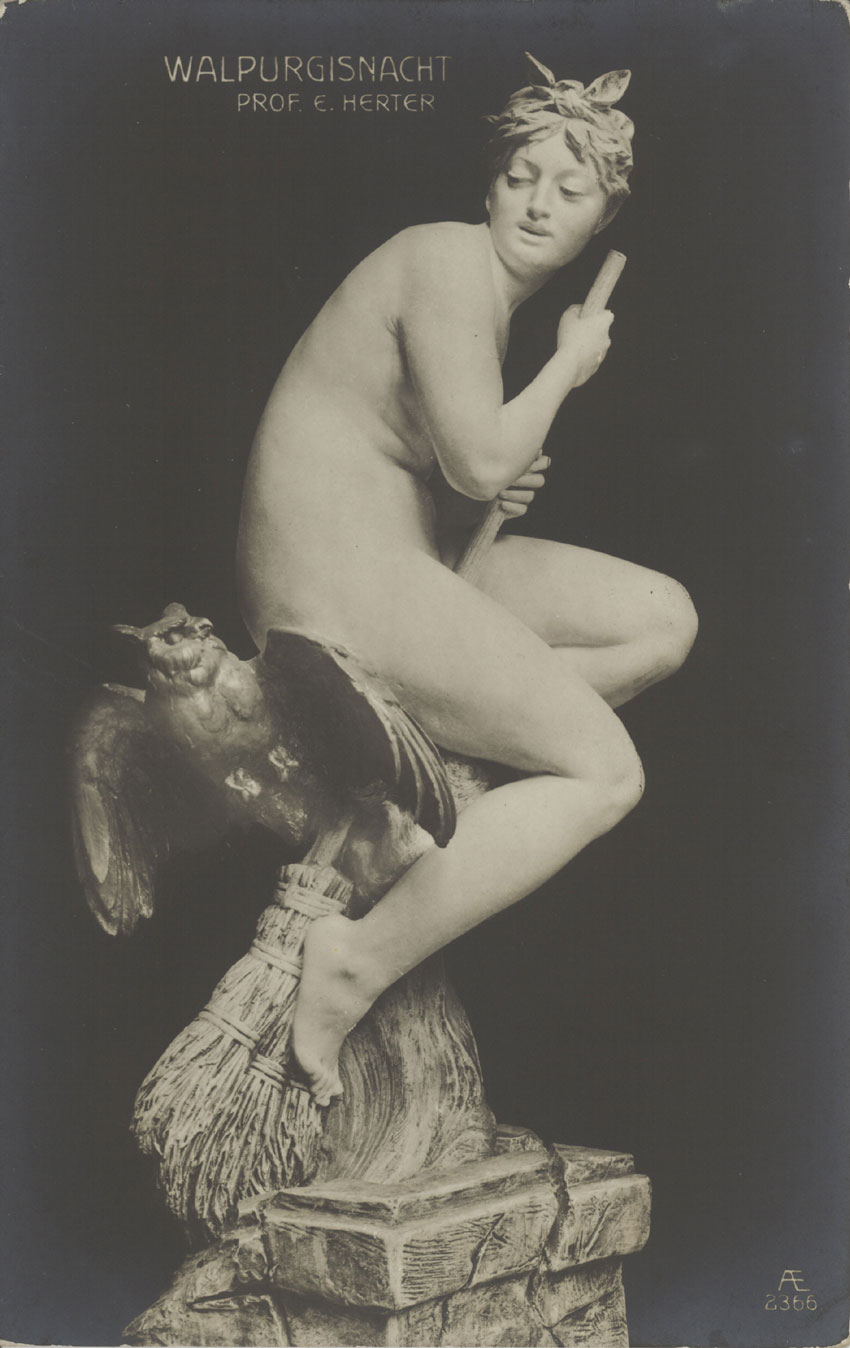

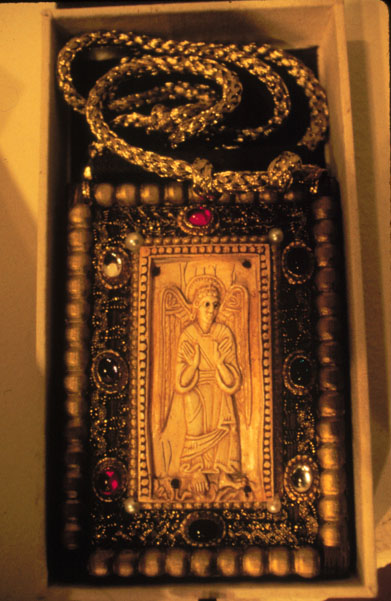

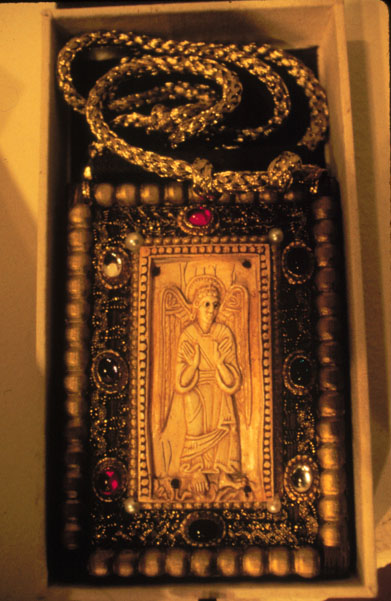

Stephanie Later illuminated her own manuscript, Solomon's Song of Songs, which beladen with jewels and a gold cord, becomes a treasure with sexual demonstrations taken from the original text portrayed.

It is an erotic poem, and so it says that Eros is the key to defeating Death, and to understanding G-D. In other words the celebration of life, of sexuality, of the pleasure principle is the source of all Gods power in the world as it is. When the lovers entwine and disappear into each other literally and figuratively, at the moment of orgasm all division disappears and the two become one; God.

For I am divided for love's sake, for the chance of union.

This is the creation of the world, that the pain of division is as nothing, and the joy of dissolution all.

Liber AL

This is known in magick as the Conversation with the Holy Guardian Angel or ones higher self. While many view the path as a solitary one, the Song of Song reveals that it cannot be, it must be a combination of both the female and the male in conjoined ecstasy. And thus the secret or lost knowledge, is that sex magick is the source of wisdom and ecstasy in the body of God. God is not only Love, God is Orgasm, dissolution of the two into one. Such an earth shaking revelation had to be hidden not because it is profane but hidden from the profane, who having power could gain even more power using this formula.

It is why Solomon the Wise, is used as a reference point in the Song. To reveal that one must have balanced the forces of light and darkness, male and female, lunar and solar, before coming into the power over the Angels and Demons, that Solomon is credited with. See my references below on this in the context of Quabbalistic Tree of Life.

For the first human created by God was not Adam but Lilith.

While rabbinical lore says she is the first wife of Adam but rejects him, she is a far older Goddess of Sumeria who is absorbed into the patriarchal Abrahamic religion as the evil one, even before the serpent.

She returns in the Song as Venus, and Babalon in the verse:

"Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?"

Of the all the figures in Midrash, it is Lilith who is most clearly Babalon. It might therefore be helpful to investigate her.

Lilith, aside from a stray reference comparing her to a "screechowl" (the translation is debatable), does not appear in the Bible itself. It is in Rabbinic midrash (presumably relying on earlier legends) that we find the full delineation of Lilith. The rabbis began with the Biblical reference to man's first creation as a bisexual being--"male and female He [God] created them [the first human]". Some of the rabbis found in this image something similar to what Aristophanes proposed in the Symposium: a dual bodied being later divided into two who must thereafter seek each other out. But others tried to take into account the later creation of Eve detailed further on in the text. If woman was created from Adam, after his initial creation, than what happened to the female created at first? The answer, according to the Midrash, was that she was Lilith; created with Adam, she refused to comply with Adam's demand that she submit herself to him, and in the end fled from him by using the Ineffable Name.

And for the Gnostics the divine was always feminine, the Sophia, the God of this world was the Devil, a materialist Master of the World, while the spirit of God was feminine the divine Sophia. In other words a Divine androgen. But she becomes a dark goddess in the new religion of Men, the light hidden in darkness.

It is in love making that the male returns to his feminine self, in orgasm masculinity disappears and the divine feminine appears. The man surrenders to his orgasm, and if in communion with his lover will disappear into her body and soul. From the two will come one, in mutual orgasm the Sophia Epistis appears regenerating the world.

In the Gnostic gospels it Mary Magdalene is described as the Sophia and as the Lover of Jesus.

The Sophia whom they call barren is the mother of the angels. And the consort of Christ is Mary Magdalen. The Lord loved Mary more than all the disciples and kissed her on her mouth often. The others said to him: ‘Why do you love her more than all of us?’ The Saviour answered and said to them: ‘Why do I not love you like her?’ There were three who walked with the Lord at all times, Mary his mother, and her sister and Magdalene, whom they called his consort. For Mary was his sister and his mother and his consort.

But as in the Song the Lover is a sister, a wife and a mother, the tri-fold form of the Goddess; Maiden, Mother, Crone.

The Song of Song is never referred to in the New Testament, except in allegory when the Mary's discover Jesus is missing. The very act of resurrection, is itself an allegory on the power of the cave, womb, and the mothers power over the son, as it is also spoken of in the Song of Songs, where Solomon is crowned by his mother.

1When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that they might go to anoint Jesus' body. 2Very early on the first day of the week, just after sunrise, they were on their way to the tomb 3and they asked each other, "Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?"

4But when they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had been rolled away. 5As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed.

6"Don't be alarmed," he said. "You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. 7But go, tell his disciples and Peter, 'He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.' "

8Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid. -- Mark 16:1-8

Like the earlier mythos of the Young God; Dionysus whose is sacrificed and whom the Bacchanes followed, we find the idea of the young sacrificed god tended over by women again in the New Testament. Like Dionysus, Jesus himself is associated with wine. Which is why it is claimed that with the coming of Christianity the Great God Pan died. Replaced by a new youthful deity of death and resurrection, ; in other words spring.

The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus. Initiates worshipped him in the Dionysian Mysteries, which were comparable to and linked with the Orphic Mysteries, and may have influenced Gnosticism and early Christianity. His female followers are called maenads (Bacchantes).

The Bacchanalia were wild and mystic festivals of the Roman god Bacchus. Introduced into Rome from lower Italy by way of Etruria (c. 200 BC), the bacchanalia were originally held in secret and attended by women only. The festivals occurred on three days of the year in the grove of Simila near the Aventine Hill, on March 16 and March 17. Later, admission to the rites was extended to men and celebrations took place five times a month. According to Livy, the extension happened in an era when the leader of the Bacchus cult was Paculla Annia - though it is now believed that some men had participated before that.

THE DEATH OF PAN

by Lord Dunsany

1915

When travellers from London entered Arcady they lamented one to

another the death of Pan.

And anon they saw him lying stiff and still.

Horned Pan was still and the dew was on his fur; he had not the look

of a live animal. And then they said, "It is true that Pan is dead."

And, standing melancholy by that huge prone body, they looked for

long at memorable Pan.

And evening came and a small star appeared.

And presently from a hamlet of some Arcadian valley, with a sound

of idle song, Arcadian maidens came.

And, when they saw there, suddenly in the twilight, that old recumbent

god, they stopped in their running and whispered among themselves.

"How silly he looks," they said, and thereat they laughed a little.

And at the sound of their laughter Pan leaped up and the gravel flew

from his hooves.

And, for as long as the travellers stood and listened, the crags and

the hill-tops of Arcady rang with the sounds of pursuit.

The persistence of the matriarchal traditions of Sophia/spirit are shown in the Song and in the New Testament. Traditions that were suppressed by the later Church Fathers.

Nowhere in scripture is Mary identified as a public sinner or a prostitute. Instead, all four Gospels show her as the primary witness to the most central events of Christian faith. She traveled with Jesus in the Galilean discipleship and, with Joanna and Susanna, supported Jesus' mission from her own financial resources (Luke 8:1-3). In the synoptic Gospels, Mary leads the group of women who witness Jesus' death and burial, the empty tomb, and his Resurrection. The synoptic Gospels also contrast Jesus' abandonment by the male disciples with the faithful strength of the women disciples who, led by Mary, accompany him in this most shameful and agonizing of deaths. Some have attributed the faithfulness of these women to a lesser risk of being crucified. Yet biblical scholarship shows that the Romans crucified women and even children in their brutal and, as it turned out, futile attempt to discourage insurrection.

That the message of the Resurrection was first entrusted to women is regarded by scripture scholars as one of the strongest proofs of the historicity of the Resurrection accounts. In Jewish law women's testimony was not recognized. Had accounts of Jesus' Resurrection been fabricated, women would never have been included as witnesses.

Thus we can see the convergence of the Bacchanae, the pagan celebration of spring, with Passover and later with Easter. Life over death. A celebration of eros.

This then is why the Song of Songs is eternal. It's sources are ancient Sumerian and Egyptian and later Canaanite love poetry, Palestinian agricultural rituals and marriage rites, that originate in matriarchal traditions, transformed into a tale for the patriarchal age. One that reminds us of the power not only of Love but of eros, and the importance of woman as the living spirit of Sophia, the secret vessel of God.

This then is the Grand Banishing of Darkness. It is used to avert the Angel of Death. Like the Gnostic Mass, which itself is also a celebration of the balance between Solar and Lunar, God and Goddess, the Song of Songs is the origin of the Gnostic Mass .

That it has become a song, or a recitation at Passover misses its real purpose; that it is a dramatic ritual, as a mass or magickal rite. One used to create life in the midst of death. Thus the secret of the universe is that the Big Bang is the Song of Songs. Life out of nothingness. This then is the lost text, the ancient secret wisdom that all Occult legends and mythologies refer to.

In the Qabalah, the 22 Paths (named after the letters of the Hebrew alphabet) connect the ten Sephiroth on the "Tree of Life." The fifteenth is the Path of Hé, which connects Tiphareth with Yesod.

P – 8

| Peh – פ – 80

| Pi − Π − π |

Table 9-4: Missing Hebrew Letters in English

| English Letter

| Hebrew Letter Source

| Tarot Symbol

|

| ght – 8

| Het – ח – 8

| Chariot

|

| ? – 9

| Tet – ט – 9

| Hermit

|

| ? – 60

| Samech – ס – 60

| Devil

|

| ? – 70

| Ayin – ע – 70

| Tower

|

| ? – 90

| Tzadik – צ – 90

| Moon |

to Frater Omnia Pro Veritate [Norman Mudd]

From Frater O. M. [Edward Aleister Crowley]

The question now arises about Netzach-Yesod which are below Tiphereth. Shall we suppose that the force conveyed by Nun, Samekh and Ayin respectively is in the reverse direction? Both currents are in motion. Netzach is the wish phantasm. Hod the conventional intellectual apprehension of the Universe. Yesod the formulation of the Ego as plastically determined by Netzach and Hod with the idea of reproducing itself not creatively. Scorpio is vibration and watery. This is why it leads to wish-phantasms. On the other side Capricornus the Devil, being a direct ecstatic outburst of the Ego, creates a point of view. The straightness of the Capricorn forces explain why a wish phantasm should be feminine and fascinating, while the "point of view," though equally illusory, is clean and free from emotion.

Tiphereth acts on Yesod through Samekh-Sagittarius, a Jupiterian force echoing the Jupiter of Chesed. It is the Paternal authority and power of creation expressed as a vector instead of a point. The Tarot trump is Temperance, illustrating the transmutation of Ego by Alchemy, with various pre [_] about to balance. The Alchemist being the feminine Angel. (Note the Archer equals Diana equals Dianus equals Jupiter.) Thus this sign connects Jupiter and the Moon. It is therefore the proper sign for the Ego to reproduce itself in things reflected in lunar form by means of process of generation.

How is Hod influenced by Netzach? Path of Pe. Very difficult.

How does Netzach affect Hod influence Yesod? Through Tzaddi-Emperor, Aries, i.e. the wish phantasm imposes itself on the image through this illusion of diving right. It is very arbitrary. Hod influences Yesod through the path of Resh which here represents the illusion of pride, vanity.

Influenced upon Netzach and Hod from Chesed and Geburah respectively. The former if the path of Jupiter, lord of fortune. This is easy. The authoritative part of the mind, its creative paternal force, determines the wish phantasm by a direct emanation of its own nature. The Wheel is, so to speak, his daughter. He manifests himself through the Wheel of Fortune, the three guanas which represent varieties chased by chance. Hence the [_] is like a series of pictures thrown on a screen by a zoetrope. How does Gebruah influence Hod? Mem. This means that the point of view is bound to necessity, as opposed to its voluntary determination by the wish of the Ego in Tiphereth through 8, the fact that this energy can only be translated into conscious perception by means of reflection i.e., the illusion of matter, and this involves the destruction of the pure energy. It looses its nature by being reflected in this way. Finally, we have Malkuth determined by this triple illusion, 7, 8, 9- Netzach, Yesod and Hod. It is the illusion which reflects these illusions through the path of Qoph-Pisces-Moon, sheer glamour, dream. The point of view imposes directly through Shin, the Last Judgement, a fixed idea which might almost be called prejudice. Yesod communicated to it through the sphere of Saturn and Earth. The darkness of the Astral.

Actually the Path of He is known as Pe. It is the path between Yesod and Tipareth whose name is Samekh and whose number is 60 and represented as 15 the Devil card in the Tarot. The Path is Pe which is 80. This path is one where the King, Solomon, must face his other, it is the abyss ruled over by a Demon King who is the reverse of Solomon. It is the secret to Solomons power over both Angels and Demons.

For Yesod is the Moon and Tipareth the Sun. In order to balance out the magickal power of the coming solar phallic religions, Solomon married many priestesses of the old religion, those whom he did not marry he had as concubines. In all around 1000 priestesses of the old religions of the lunar current. He built his temple in the centre of circles of lunar temples.

There are threescore queens, and fourscore concubines, and virgins without number. My dove, my undefiled is but one; she is the only one of her mother, she is the choice one of her that bare her. The daughters saw her, and blessed her; yea, the queens and the concubines, and they praised her.

In order to become Wise, Solomon engaged in old magicks of the Qabbala and took the hard path of Samekh, a direct path between Yesod and Tipareth.

Samekh in gematria has the value 60.

Samekh and Mem form the abbreviation for the Angel of Death, whose name in Hebrew is Samael. It also stands for centimetre.

This meant he had to balance angelic and demonic hosts, black and white, lunar solar, feminine and masculine, and overcome them.

The key here is the reference to Sixty Swordsmen, though at least one text translates this as Swords women, which is Samekh. The idea of swords women refers back to the Canaanite origins of the Song, which refers to threshing women, not so much warriors but the agricultural tool of the scythe, and again a reference to the matriarchal age which was passing.

This is seen in the passage that refers to Venus, Babalon, which also is known as the Morningstar or Lucifer, the androgynous deity.

Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?

Solomon's reign was one of peace with his neighbours. Islam calls him Suleiman, and he is considered sacred to the Muslims as well.His building of the Temple was aided by a trade deal with Hiram of Tyre, who provided the ceders of Lebanon in exchange for war chariots. Thus the chariot imagery in the Song of Songs. The Chariots cost 666 gold talens. This is the first time that 666 is referenced in the bible but only in exigency. Thus Solomon, the Man of the Sun is 666.

In order to gain his power he had to have used the Gematria of the Tree of Life, that is he one of the only historical figures in the bible to have traveled up the Tree to learn the true face of God. In doing so he also had to go into the abyss, the path of Samekh, to find and confront his other self. His demon self.

All later magickal and occult works refer back to Solomon, including the Freemasons whose self professed secret knowledge, Gnosis again, are the secrets of the building of the Temple.

All later magickal and occult works refer back to Solomon, including the Freemasons whose self professed secret knowledge, Gnosis again, are the secrets of the building of the Temple.

All modern magick and Occult mythology comes from the myths surrounding Solomon his ordeal on the Tree of Life, his building of the temple, his political marriage of solar phallic power with the ancient cave, womb power of the early goddess cultus.

In the Song of Songs we have the revelation of the path and way that he came to his power through the Qabbala. The clues are in the passages describing his chariot, which is really an allegory on his temple.

King Solomon made himself a chariot of the wood of Lebanon. He made the pillars thereof of silver, the bottom thereof of gold, the covering of it of purple, the midst thereof being paved with love, for the daughters of Jerusalem.

This interpretation is underlined by a passage in Crowley's Commentary to Liber LXV (The Book of the Heart Girt with the Serpent): Pe is the letter of Atu XVI the 'House of God' or 'Blasted Tower'. The hieroglyph represents a Tower - symbolic of the ego in its phallic aspect, yet shut up, i.e. separate. This Tower is smitten by the Lightning Flash of illumination, the impact of the H.G.A. and the Flaming Sword of the Energy that proceeds from Kether to Malkuth. Thence are cast forth two figures representing by their attitude the letter Ayin: these are the twins (Horus and Harpocrates) born at the breaking open of the Womb of the m other (the second aspect of The Tower as 'a spring shut up, a fountain sealed').

This passage underlines the mention earlier of Geburah 'applied to' the egg, the lightning flash being in this context a type of Geburah. We have, then, an identity between the Tao and the Cup of Babalon, both being Perfection; and, of course, 'The Perfect and the Perfect are one Perfect and not two; nay, are none!" (AL I.45). The reference to 'a spring shut up, a fountain sealed' is from the Song of Solomon: A garden barred is my sister, my bride, a spring shut up, a fountain sealed.

Passover in 2007 will commence just after sundown on the evening of Monday, April 2, 2007. For those who celebrate Passover for 7 days (most Reform Jews, some Conservative Jews, and Jews living in Israel), Passover in 2007 will end at sundown on the evening of Monday, April 9, 2007.

For those who celebrate Passover for 8 days [Jews living outside of Israel (with the aforementioned exception of most Reform Jews and some Conservative Jews), otherwise known as Diaspora Jews, where the word "diaspora" is derived from Greek and means either "dispersion" or "scattering". In Hebrew, the equivalent words are "Tefutzah", meaning "scattered", or "Galut", meaning "exile". Diaspora, Tefutzah, and Galut all refer to the Jewish people being dispersed among all the other nations outside of Israel], Passover in 2007 will end at sundown on the evening of Tuesday, April 10, 2007.

The name Passover (Pesakh, meaning "skipping" or passing over)Feast of Unleavened Bread (Chag Ha'Matsot) refers to the weeklong period when leaven has been removed, derives from the night of the Tenth Plague, when the Angel of Death saw the blood of the Passover lamb on the doorposts of the houses of Israel and "skipped over" them and did not kill their firstborn. The meal of the Passover Seder commemorates this event. The name and unleavened bread or matzo ("flatbread") is eaten.

derives from the night of the Tenth Plague, when the Angel of Death saw the blood of the Passover lamb on the doorposts of the houses of Israel and "skipped over" them and did not kill their firstborn. The meal of the Passover Seder commemorates this event. The name and unleavened bread or matzo ("flatbread") is eaten.

The term Pesach (Hebrew: פֶּסַח) or, more exactly, the verb "pasàch" (Hebrew: פָּסַח) is first mentioned in the Torah account of the Exodus from Egypt (Exodus 12:23). It is found in Moses' words that God "will pass over" the houses of the Israelites during the final plague of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, the killing of the first-born. On the night of that plague, which occurred on the 15th day of Nisan, the Israelites smeared their lintels and doorposts with the blood of the Passover sacrifice and were spared.

In Exodus 12:12, when God inflicts the tenth and final plague on Egypt (the death of the firstborn), it is said that Azrael was the one that actually came and took the souls of the firstborn.

There is no other book of the Bible as sensuous as The Song of Songs.

"O give me the kisses of your mouth," the first chapter reads, "for your love is more delightful than wine." And in another place, "My beloved has gone down to his garden, to the beds of spices, to browse in the gardens and to pick lilies. I am my beloved's and my beloved is mine."

"O give me the kisses of your mouth," the first chapter reads, "for your love is more delightful than wine." And in another place, "My beloved has gone down to his garden, to the beds of spices, to browse in the gardens and to pick lilies. I am my beloved's and my beloved is mine."

The Song of Songs, Shir Hashirim as it is known in Hebrew, is read during the festival of Passover, which this year began at sundown Monday. An original illuminated manuscript of the song, on display at the Oregon Jewish Museum, reveals the enduring beauty of this unusual biblical text.

"The whole Torah is Holy," says Rabbi Akiva, "but The Song of

"The whole Torah is Holy," says Rabbi Akiva, "but The Song of

Songs is the Holy of Holies."

When it came time to decide which of the ancient books would become part of the canon for Israel, there was a big argument about this beloved text, sometimes called "The Song of Solomon."

Nowhere in it does the name of God appear; its words were sung in every tavern; it glorifies the sexual love between a man and woman who were clearly not married; it celebrates Nature and the pleasures of the body.

Yet, despite vociferous opposition, the opinion of Rabbi Akiva who was a great mystic and an important leader of his time (1st century Israel) held sway, and the Song of Songs was preserved as one of the Holy books of Torah.

SONG OF SONGS

The five scrolls in the Bible are connected to the Jewish Holy Days:

Ecclesiastes - Succoth

Esther - Purim

Song of Songs - Passover

Ruth - Shavuoth

Lamentations - Tish'a Be'av

According to Jewish tradition, the Song of Songs was written by King Solomon ("the Song of Songs by Solomon" (11,1)), as were also the books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes.

In the Song of Songs, the main feeling is of the blossoming of nature, love and awakening beauty which are the motifs of spring time, and as Passover is also celebrated in spring time it was suitable to read this scroll during Passover. Another reason may be the mention of the chariots of Pharaoh in the Song of Songs.

Sephardi Jews read this scroll at the end of the Haggadah reading, while Ashkenazi Jews read it at the synagogue on the Saturday after the beginning of Passover.

Although this book is unique in the Bible, it is common among literature of the Ancient Near East. There is a long history of love poetry in Egypt and Mesopotamia, and Israel was probably no exception. The song has many of the common features of Hebrew poetry but does seem to have been weaved together from many sources given its different types of Hebrew.

Although this book is unique in the Bible, it is common among literature of the Ancient Near East. There is a long history of love poetry in Egypt and Mesopotamia, and Israel was probably no exception. The song has many of the common features of Hebrew poetry but does seem to have been weaved together from many sources given its different types of Hebrew.

Despite how short the book is, much has been written about it. Part of the reason for this is that people feel compelled to explain why it is included in the Bible in the first place given its seemingly secular nature.

Around the close of the 1st century CE there were great debates about whether or not it should be included in the Biblical canon. Even with all the discussion and scholarship, there is still a great deal of debate about the book's unity, origin, purpose, date, how many characters are speaking and who they are.

Song of Solomon

Although the book never mentions God by name, an allegorical interpretation justified its inclusion in the Biblical canon. According to Jewish tradition in the Midrash and the Targum, it is an allegory of God's love for the Children of Israel. In Christian tradition that began with Origen, it is allegory for the relationship of Christ and the Church or Christ and the individual believer (see the Sermons on the Song of Songs by Bernard of Clairvaux). This type of allegorical interpretation was applied later to even passing details in parables of Jesus. It is also heavily used in Sufi poetry.

Frederick Hollyer, photograph of painting 'The Song of Songs no. 7 "His pavilion over me was love"' by Simeon Solomon, 1878. Museum no. 276-1931

English Translation by Jay C. Treat

The Targum to Song of Songs is available in both European and Yemenite manuscripts. The Aramaic text used in this translation is that of Raphael Hai Melamed, “The Targum to Canticles According to Six Yemen Mss. Compared with the ‘Textus Receptus’ (Ed. de Lagarde),” Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, 10 (1919-20): 377-410, 11 (1920-21): 1-20, and 12 (1921-22): 57-117.

This translation began as an adaptation of the translation by Marvin H. Pope, Song of Songs: A New Translation and Commentary, The Anchor Bible 7C (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1977).

SONG OF SONGS scroll Shir Ha-Shirim - kosher illuminated parchment scroll

| | | Full illuminated Song of Songs scroll |

|

|

|

|

The Song of Songs, etching by Zely Smekhov

| These pages are from The Song of Songs which includes six etchings by Zely Smekhov and Hebrew calligraphy by David Moss. It includes a new English translation by Yoni Moss in a limited edition of 137 copies. Printed by hand at the Officina Bodoni, Verona, Italy. The handmade paper bearing the Bet Alpha Editions watermark was produced at the Magnini paper mill, Pescia, Italy, for Bet Alpha Editions, Berkeley, CA, 1999. |

| |

Canticum Canticorum Salomonis

(The Song of Songs)

PRO CANTIONE ANTIQUA / BRUNO TURNER

Compact Disc CDH55095

'One of Palestrina's most sublime and expressive works ... an excellently balanced and natural-sounding recording' (The Penguin Guide to Compact Discs)

Palestrina: Canticum Canticorum Salomonis (The Song of Songs) - Osculetur me osculo oris sui [2'53]

Palestrina: Canticum Canticorum Salomonis (The Song of Songs) - Osculetur me osculo oris sui [2'53]

Chapter 1

- The song of songs, which is Solomon's.

- Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth: for thy love is better than wine.

- Because of the savour of thy good ointments thy name is as ointment poured forth, therefore do the virgins love thee.

- Draw me, we will run after thee: the king hath brought me into his chambers: we will be glad and rejoice in thee, we will remember thy love more than wine: the upright love thee.

- I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar, as the curtains of Solomon.

- Look not upon me, because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me: my mother's children were angry with me; they made me the keeper of the vineyards; but mine own vineyard have I not kept.

- Tell me, O thou whom my soul loveth, where thou feedest, where thou makest thy flock to rest at noon: for why should I be as one that turneth aside by the flocks of thy companions?

- If thou know not, O thou fairest among women, go thy way forth by the footsteps of the flock, and feed thy kids beside the shepherds' tents.

- I have compared thee, O my love, to a company of horses in Pharaoh's chariots.

- Thy cheeks are comely with rows of jewels, thy neck with chains of gold.

- We will make thee borders of gold with studs of silver.

- While the king sitteth at his table, my spikenard sendeth forth the smell thereof.

- A bundle of myrrh is my well-beloved unto me; he shall lie all night betwixt my breasts.

- My beloved is unto me as a cluster of camphire in the vineyards of Engedi.

- Behold, thou art fair, my love; behold, thou art fair; thou hast doves' eyes.

- Behold, thou art fair, my beloved, yea, pleasant: also our bed is green.

- The beams of our house are cedar, and our rafters of fir.

Chapter 2

- I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys.

- As the lily among thorns, so is my love among the daughters.

- As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste.

- He brought me to the banqueting house, and his banner over me was love.

- Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples: for I am sick of love.

- His left hand is under my head, and his right hand doth embrace me.

- I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, till he please.

- The voice of my beloved! behold, he cometh leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills.

- My beloved is like a roe or a young hart: behold, he standeth behind our wall, he looketh forth at the windows, shewing himself through the lattice.

- My beloved spake, and said unto me, Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away.

- For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone;

- The flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come, and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land;

- The fig tree putteth forth her green figs, and the vines with the tender grape give a good smell. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

- O my dove, that art in the clefts of the rock, in the secret places of the stairs, let me see thy countenance, let me hear thy voice; for sweet is thy voice, and thy countenance is comely.

- Take us the foxes, the little foxes, that spoil the vines: for our vines have tender grapes.

- My beloved is mine, and I am his: he feedeth among the lilies.

- Until the day break, and the shadows flee away, turn, my beloved, and be thou like a roe or a young hart upon the mountains of Bether.

Chapter 3

- By night on my bed I sought him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, but I found him not.

- I will rise now, and go about the city in the streets, and in the broad ways I will seek him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, but I found him not.

- The watchmen that go about the city found me: to whom I said, Saw ye him whom my soul loveth?

- It was but a little that I passed from them, but I found him whom my soul loveth: I held him, and would not let him go, until I had brought him into my mother's house, and into the chamber of her that conceived me.

- I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, till he please.

- Who is this that cometh out of the wilderness like pillars of smoke, perfumed with myrrh and frankincense, with all powders of the merchant?

- Behold his bed, which is Solomon's; threescore valiant men are about it, of the valiant of Israel.

- They all hold swords, being expert in war: every man hath his sword upon his thigh because of fear in the night.

- King Solomon made himself a chariot of the wood of Lebanon.

- He made the pillars thereof of silver, the bottom thereof of gold, the covering of it of purple, the midst thereof being paved with love, for the daughters of Jerusalem.

- Go forth, O ye daughters of Zion, and behold king Solomon with the crown wherewith his mother crowned him in the day of his espousals, and in the day of the gladness of his heart.

Chapter 4

- Behold, thou art fair, my love; behold, thou art fair; thou hast doves' eyes within thy locks: thy hair is as a flock of goats, that appear from mount Gilead.

- Thy teeth are like a flock of sheep that are even shorn, which came up from the washing; whereof every one bear twins, and none is barren among them.

- Thy lips are like a thread of scarlet, and thy speech is comely: thy temples are like a piece of a pomegranate within thy locks.

- Thy neck is like the tower of David builded for an armoury, whereon there hang a thousand bucklers, all shields of mighty men.

- Thy two breasts are like two young roes that are twins, which feed among the lilies.

- Until the day break, and the shadows flee away, I will get me to the mountain of myrrh, and to the hill of frankincense.

- Thou art all fair, my love; there is no spot in thee.

- Come with me from Lebanon, my spouse, with me from Lebanon: look from the top of Amana, from the top of Shenir and Hermon, from the lions' dens, from the mountains of the leopards.

- Thou hast ravished my heart, my sister, my spouse; thou hast ravished my heart with one of thine eyes, with one chain of thy neck.

- How fair is thy love, my sister, my spouse! how much better is thy love than wine! and the smell of thine ointments than all spices!

- Thy lips, O my spouse, drop as the honeycomb: honey and milk are under thy tongue; and the smell of thy garments is like the smell of Lebanon.

- A garden inclosed is my sister, my spouse; a spring shut up, a fountain sealed.

- Thy plants are an orchard of pomegranates, with pleasant fruits; camphire, with spikenard,

- Spikenard and saffron; calamus and cinnamon, with all trees of frankincense; myrrh and aloes, with all the chief spices:

- A fountain of gardens, a well of living waters, and streams from Lebanon.

- Awake, O north wind; and come, thou south; blow upon my garden, that the spices thereof may flow out. Let my beloved come into his garden, and eat his pleasant fruits.

Chapter 5

- I am come into my garden, my sister, my spouse: I have gathered my myrrh with my spice; I have eaten my honeycomb with my honey; I have drunk my wine with my milk: eat, O friends; drink, yea, drink abundantly, O beloved.

- I sleep, but my heart waketh: it is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying, Open to me, my sister, my love, my dove, my undefiled: for my head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of the night.

- I have put off my coat; how shall I put it on? I have washed my feet; how shall I defile them?

- My beloved put in his hand by the hole of the door, and my bowels were moved for him.

- I rose up to open to my beloved; and my hands dropped with myrrh, and my fingers with sweet smelling myrrh, upon the handles of the lock.

- I opened to my beloved; but my beloved had withdrawn himself, and was gone: my soul failed when he spake: I sought him, but I could not find him; I called him, but he gave me no answer.

- The watchmen that went about the city found me, they smote me, they wounded me; the keepers of the walls took away my veil from me.

- I charge you, O daughters of Jerusalem, if ye find my beloved, that ye tell him, that I am sick of love.

- What is thy beloved more than another beloved, O thou fairest among women? what is thy beloved more than another beloved, that thou dost so charge us?

- My beloved is white and ruddy, the chiefest among ten thousand.

- His head is as the most fine gold, his locks are bushy, and black as a raven.

- His eyes are as the eyes of doves by the rivers of waters, washed with milk, and fitly set.

- His cheeks are as a bed of spices, as sweet flowers: his lips like lilies, dropping sweet smelling myrrh.

- His hands are as gold rings set with the beryl: his belly is as bright ivory overlaid with sapphires.

- His legs are as pillars of marble, set upon sockets of fine gold: his countenance is as Lebanon, excellent as the cedars.

- His mouth is most sweet: yea, he is altogether lovely. This is my beloved, and this is my friend, O daughters of Jerusalem.

Chapter 6

- Whither is thy beloved gone, O thou fairest among women? whither is thy beloved turned aside? that we may seek him with thee.

- My beloved is gone down into his garden, to the beds of spices, to feed in the gardens, and to gather lilies.

- I am my beloved's, and my beloved is mine: he feedeth among the lilies.

- Thou art beautiful, O my love, as Tirzah, comely as Jerusalem, terrible as an army with banners.

- Turn away thine eyes from me, for they have overcome me: thy hair is as a flock of goats that appear from Gilead.

- Thy teeth are as a flock of sheep which go up from the washing, whereof every one beareth twins, and there is not one barren among them.

- As a piece of a pomegranate are thy temples within thy locks.

- There are threescore queens, and fourscore concubines, and virgins without number.

- My dove, my undefiled is but one; she is the only one of her mother, she is the choice one of her that bare her. The daughters saw her, and blessed her; yea, the queens and the concubines, and they praised her.

- Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?

- I went down into the garden of nuts to see the fruits of the valley, and to see whether the vine flourished and the pomegranates budded.

- Or ever I was aware, my soul made me like the chariots of Amminadib.

- Return, return, O Shulamite; return, return, that we may look upon thee. What will ye see in the Shulamite? As it were the company of two armies.

Chapter 7

- How beautiful are thy feet with shoes, O prince's daughter! the joints of thy thighs are like jewels, the work of the hands of a cunning workman.

- Thy navel is like a round goblet, which wanteth not liquor: thy belly is like an heap of wheat set about with lilies.

- Thy two breasts are like two young roes that are twins.

- Thy neck is as a tower of ivory; thine eyes like the fishpools in Heshbon, by the gate of Bathrabbim: thy nose is as the tower of Lebanon which looketh toward Damascus.

- Thine head upon thee is like Carmel, and the hair of thine head like purple; the king is held in the galleries.

- How fair and how pleasant art thou, O love, for delights!

- This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes.

- I said, I will go up to the palm tree, I will take hold of the boughs thereof: now also thy breasts shall be as clusters of the vine, and the smell of thy nose like apples;

- And the roof of thy mouth like the best wine for my beloved, that goeth down sweetly, causing the lips of those that are asleep to speak.

- I am my beloved's, and his desire is toward me.

- Come, my beloved, let us go forth into the field; let us lodge in the villages.

- Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves.

- The mandrakes give a smell, and at our gates are all manner of pleasant fruits, new and old, which I have laid up for thee, O my beloved.

Chapter 8

- O that thou wert as my brother, that sucked the breasts of my mother! when I should find thee without, I would kiss thee; yea, I should not be despised.

- I would lead thee, and bring thee into my mother's house, who would instruct me: I would cause thee to drink of spiced wine of the juice of my pomegranate.

- His left hand should be under my head, and his right hand should embrace me.

- I charge you, O daughters of Jerusalem, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, until he please.

- Who is this that cometh up from the wilderness, leaning upon her beloved? I raised thee up under the apple tree: there thy mother brought thee forth: there she brought thee forth that bare thee.

- Set me as a seal upon thine heart, as a seal upon thine arm: for love is strong as death; jealousy is cruel as the grave: the coals thereof are coals of fire, which hath a most vehement flame.

- Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it: if a man would give all the substance of his house for love, it would utterly be contemned.

- We have a little sister, and she hath no breasts: what shall we do for our sister in the day when she shall be spoken for?

- If she be a wall, we will build upon her a palace of silver: and if she be a door, we will inclose her with boards of cedar.

- I am a wall, and my breasts like towers: then was I in his eyes as one that found favour.

- Solomon had a vineyard at Baalhamon; he let out the vineyard unto keepers; every one for the fruit thereof was to bring a thousand pieces of silver.

- My vineyard, which is mine, is before me: thou, O Solomon, must have a thousand, and those that keep the fruit thereof two hundred.

- Thou that dwellest in the gardens, the companions hearken to thy voice: cause me to hear it.

- Make haste, my beloved, and be thou like to a roe or to a young hart upon the mountains of spices.

Love poetry

The ancient Egyptians excelled in writing romantic love poetry. In addition eulogies to Nile River and its merits, there were many love poems that expressed not only vehement poison surging the heart of a lover, but also delicate emotions. Sentiments of love were couched in beautiful similes derived from the aesthetic aspects of Egyptian environment. For example, a lover says to his beloved, “My beloved is like a garden, full of beautiful papyrus blossoms and I am like a wild goose attracted by the taste of love”.

Another lover says, “My beloved is there on the other bank. We are separated by the floodwater. On the bankside, there is a crocodile lying in wait. But I am not afraid of it. I will swim through the water until I reach her and be delighted.”

In another love song, two lovers exchange most refined expressions of love. The loving woman says, “I will never leave you my darling. My only wish is to stay in your house and at your service. We will always be hand in hand, come and go to gather everywhere. You are my health; my life.”

It is to be noted that in many of the love poems in ancient Egypt, the man calls his beloved as “sister” and the woman calls her lover as “brother” in order to show how each one of them highly appreciates the other and rises him.

More lovely than all other womanhood, luminous, perfect

A star coming over the sky-line at new year, a good year,

Splendid in colors, with allure in the eye's turn.

Her lips are enchantment, her neck the right length and her breasts a marvel;

Her hair lapis lazuli in its glitter, her arms more splendid than gold.

Her fingers make me see petals, the lotus' are like that.

Her flanks are modeled as should be, her legs beyond all other beauty.

Noble her walking

My heart would be a slave should she enfold me.

Ancient Egyptian/Hieroglyphic poem

Miscellaneous Poems: Egyptian: Conversations in Courtship (1960); Kenner, Hugh (ed.): The Translations of Ezra Pound. Westport,CT: Greenwood Press, 1963.

Ancient songs and poetry written around the 1,000 B.C. vary greatly from culture to culture. The Chinese lyric poetry found in “The Book of Songs” tells of lovers and passion which are retrained by honor and of the conservative exchange of gifts during courtship. The lovers are restless but willing to wait to honor the fair and beautiful maidens. Egyptian poetry however, also written around 1,000 B.C. has a completely different style. The themes and words of the poems are much more erotic based and rather than conservative courtship are much more liberal in their attitude toward sex where the women are also active participants. These two different approaches are highly reflective of the Chinese and Egyptian cultures during this time period. The Chinese “Book of Songs” is considered as a text which depicts the morals valued by the Chinese culture while the Egyptian love poems reflect the Egyptian culture at the time where men and women interacted on a more liberal level and their society accepted erotica as found in other artifacts of that time period.

The Flower Song (Excerpt)

To hear your voice is pomegranate wine to me:

I draw life from hearing it.

Could I see you with every glance,

It would be better for me

Than to eat or to drink.

I. Your love has penetrated all within me

Like honey plunged into water,

Like an odor which penetrates spices,

As when one mixes juice in... ......

Nevertheless you run to seek your sister,

Like the steed upon the battlefield,

As the warrior rolls along on the spokes of his wheels.

For heaven makes your love

Like the advance of flames in straw,

And its longing like the downward swoop of a hawk.

II. Disturbed is the condition of my pool.

The mouth of my sister is a rosebud.

Her breast is a perfume.

Her arm is a............bough

Which offers a delusive seat.

Her forehead is a snare of meryu-wood.

I am a wild goose, a hunted one,

My gaze is at your hair,

At a bait under the trap

That is to catch me.

LOVE POEM

I find my love fishing

His feet in the shallows

We have breakfast together,

And drink beer.

I offer him the magic of my thighs

He is caught in my spell.

--Anonymous (Egypt 1567-1085 B.C.)

See:

For a Ruthless Criticism of Everything Existing

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

Judas, Jesus, Gnostic, Gospels, Easter, Passover, SophiaEros, Gnostics, Aliester Crowley, Cabala, Tree of Life, Christianity, Venus, Lucifer, Morning Star, Song of Songs, planet, cosmology, magick, gnostic