Sarah Green Carmichael

NEW YORK – It seems people can go hardly a week without a viral video clip from a virtual all-hands meeting.

In one of the most recent, Mr James Clarke, chief executive officer of media company Clearlink, is trying to justify a return-to-office mandate at the digital marketing and technology company when he suddenly suffers an acute case of rapid-onset foot-in-mouth syndrome.

In the section of the video that has ruffled the most feathers, he seems to be speaking to employees who want to continue to work remotely because they have been unable to find childcare.

“Only the rarest of full-time caregivers can also be a productive and full-time employee at the same time,” he says.

The comment has sparked outrage – and confusion. I don’t know any mum or dad who considers themselves a “part-time” parent. And plenty of working parents consider themselves primary caregivers, even if their child is in daycare 50 hours a week.

But in the context of his larger comments, it seems to me that Mr Clarke is worried about employees who say they need to keep working remotely because they do not have other daycare arrangements and their children are too young to go to school.

And I am sorry to say that, however clumsy his words, he is not wrong.

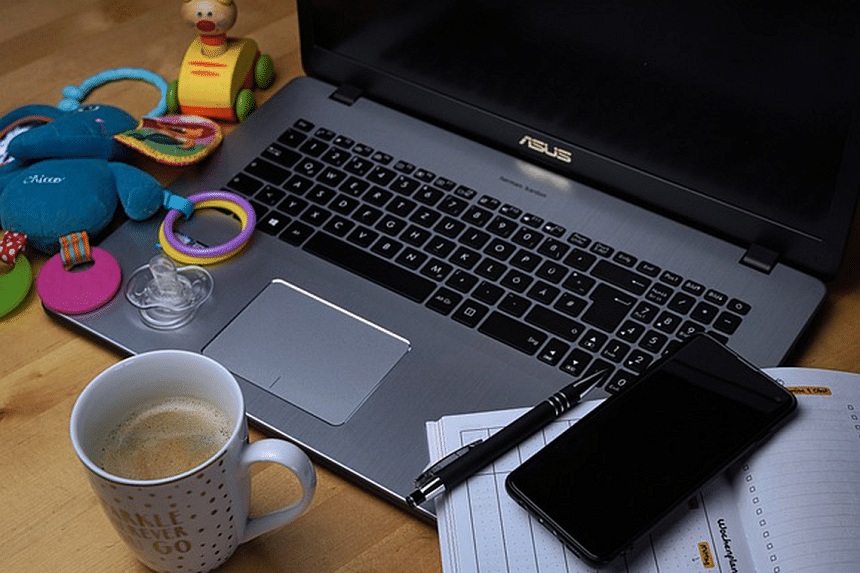

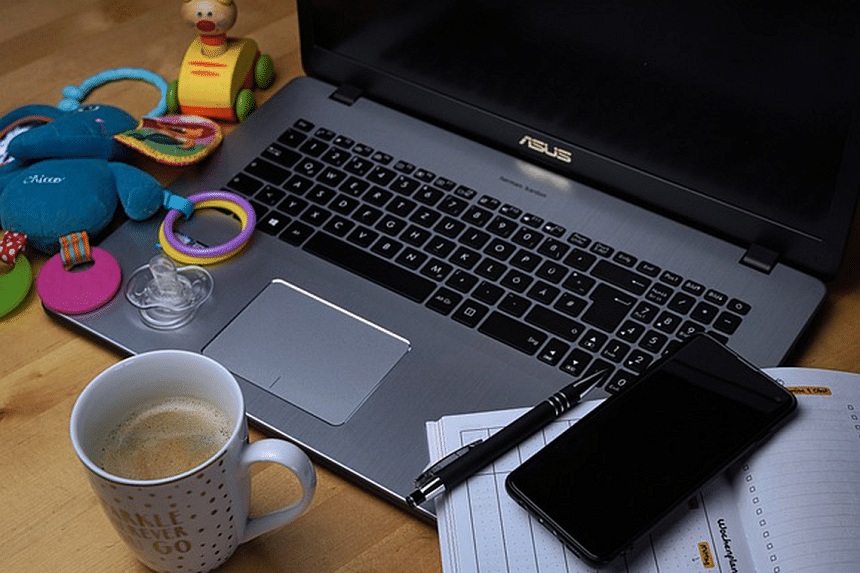

It is generally not a good idea to work full-time from home without some form of daycare for young children. For evidence, look no further than the first 18 months of the pandemic.

I spoke with Ms Jill Koziol, CEO of Motherly, a fully remote content company that requires all employees to have childcare.

“To cut out the commute time is such a gift to your employees and to families – and frankly, brings you more loyal and committed and productive employees,” she says.

But operating as a fully remote company requires openness and transparency – from both managers and employees.

Ms Koziol says they ask employees about their childcare arrangements as part of one-on-one conversations and in the context of the company’s flexibility benefits.

Employees are expected to work eight hours a day, at least six of which should be between 9am and 5pm in their local time zone. Approaching childcare conversations this way helps balance expectation-setting with empathy.

Data on how many remote employees are trying to get by without any outside childcare are hard to come by.

An estimate from Motherly’s annual survey of thousands of mothers suggests it could be about 7 per cent of full-time remote working mums.

In one of the most recent, Mr James Clarke, chief executive officer of media company Clearlink, is trying to justify a return-to-office mandate at the digital marketing and technology company when he suddenly suffers an acute case of rapid-onset foot-in-mouth syndrome.

In the section of the video that has ruffled the most feathers, he seems to be speaking to employees who want to continue to work remotely because they have been unable to find childcare.

“Only the rarest of full-time caregivers can also be a productive and full-time employee at the same time,” he says.

The comment has sparked outrage – and confusion. I don’t know any mum or dad who considers themselves a “part-time” parent. And plenty of working parents consider themselves primary caregivers, even if their child is in daycare 50 hours a week.

But in the context of his larger comments, it seems to me that Mr Clarke is worried about employees who say they need to keep working remotely because they do not have other daycare arrangements and their children are too young to go to school.

And I am sorry to say that, however clumsy his words, he is not wrong.

It is generally not a good idea to work full-time from home without some form of daycare for young children. For evidence, look no further than the first 18 months of the pandemic.

I spoke with Ms Jill Koziol, CEO of Motherly, a fully remote content company that requires all employees to have childcare.

“To cut out the commute time is such a gift to your employees and to families – and frankly, brings you more loyal and committed and productive employees,” she says.

But operating as a fully remote company requires openness and transparency – from both managers and employees.

Ms Koziol says they ask employees about their childcare arrangements as part of one-on-one conversations and in the context of the company’s flexibility benefits.

Employees are expected to work eight hours a day, at least six of which should be between 9am and 5pm in their local time zone. Approaching childcare conversations this way helps balance expectation-setting with empathy.

Data on how many remote employees are trying to get by without any outside childcare are hard to come by.

An estimate from Motherly’s annual survey of thousands of mothers suggests it could be about 7 per cent of full-time remote working mums.

The new normal of hybrid work

Although that is a small share, it has not stopped employers from worrying about it – or from making assumptions about what mothers are doing when they are working remotely. (And I am specifically using the word “mother” here because no one seems to make these assumptions about dads with remote jobs.)

For months now, when I have interviewed experts and leaders about the return to office and I bring up the challenges faced by parents, some of the men I spoke to have left me with the distinct impression they think mums (always mums) want to keep working remotely not to save time on commuting, but to simultaneously care for young children.

As a toddler mum myself, I cannot imagine anything more hellacious. Yes, during the height of Covid-19, when families were isolating and schools and daycares were closed, many parents did have kids at home during working hours.

But families found this excruciating.

Kids were on screens all day, partners were parenting and working in alternating shifts, and days were long – a patchwork of Zoom calls and Elmo marathons stretching from dawn to midnight.

A FlexJobs survey from spring 2021 shows the toll: 21 per cent of working parents had to reduce their hours; 16 per cent had to quit their jobs; and 40 per cent said they worked too long and could not unplug.

As daycare centres and schools reopened, and vaccines became available for everyone but infants, parents gratefully put this chaos behind them.

Yet, isolated anecdotes make it clear that there are likely still some parents who are trying to work remotely with children at home.

For these outliers, there are probably challenges of availability and access – but the main challenge is likely cost.

In Utah, where Mr Clearlink is based, the average annual cost of infant daycare is US$16,572 (S$22,105).

Utah also has the highest number of children in a family, with about 2.32 kids each household. Daycare for one baby and one toddler would cost about US$28,608. The average salary for women in the state is only US$23,000.

I cannot blame families for wanting to keep exorbitant daycare costs down. But remote jobs are not the answer to America’s broken childcare system.

Ms Koziol has advice for employees who want to keep working remotely: Combat any unspoken employer fears by being explicit that you have full-time, outside-the-home daycare.

UK childcare enrolments jump after squeeze on household income

On video calls, keep your camera on, both to make communication easier and to show that your home workspace is free of distractions. If there are occasionally children appearing in your Zoom calls, explain why it is an exception: Kiddo is home sick that day or daycare centre is closed due to weather.

Managers who are concerned about employees’ remote-work arrangements need to deal with them on an individual basis, not at all-hands meetings. Surely more companies could adopt Motherly’s “core hours” approach to flexibility.

But more broadly, what would really help diffuse the tension over employees’ childcare arrangements is better childcare – childcare that is easier to find, easier to pay for and higher quality. But that will likely take government intervention.

It would be a worthy investment.

“Our economy needs mothers in the workforce,” says Ms Koziol. “We are losing our competitive edge. Millennial women are the most educated demographic in our economy. We’ve got to find a way to make it work for them.”

Remote work is one way to do that. But remote work only works in conjunction with childcare.

BLOOMBERG

Sarah Green Carmichael is a Bloomberg Opinion editor. Previously, she was managing editor of ideas and commentary at Barron’s and an executive editor at Harvard Business Review, where she hosted HBR IdeaCast.

No comments:

Post a Comment