Fusion Technology to Revolutionize Geothermal Power

- Geothermal energy has the potential to provide an almost infinite source of clean energy, but current technology limits its accessibility to specific locations.

- Researchers are investigating the use of gyrotrons, a technology used in nuclear fusion, to drill deeper and more efficiently, potentially revolutionizing geothermal energy production.

- Breakthroughs in deep drilling technology could make geothermal energy a globally viable solution, significantly impacting the future of energy and the fight against climate change.

The Earth’s core produces so much heat that if we could tap just one tenth of one percent of it, the world’s energy needs would be satisfied for the next 20 million years. And that infinite source of power would yield zero greenhouse gases in the process. But while geothermal energy thrives today in places like Iceland, where heat from the Earth’s core naturally comes up to the surface of the Earth’s crust, for the rest of the world it remains out of reach.

At present, geothermal accounts for a mere 0.5% of renewable energy on a global scale. And growing that share will require some serious technological breakthroughs. “To grow as a national solution, geothermal must overcome significant technical and non-technical barriers in order to reduce cost and risk,” says the introduction to a 2019 U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) report — GeoVision: Harnessing the Heat Beneath Our Feet. “The subsurface exploration required for geothermal energy is foremost among these barriers, given the expense, complexity, and risk of such activities.”

But scientists are hard at work trying to figure out a way to tap into that heat from anywhere on the planet. All it will require is digging the deepest hole in human history. The Earth's crust varies from about 3 to 47 miles in thickness, and most of those thin bits are way out in the deepest parts of our oceans. So far, the deepest humans have ever dug was a vertical depth of just 12,289 meters (40,318 feet or just over 7.6359848 miles) way back in 1989. And in that project, the Russian Kola Superdeep Borehole, was deemed a failure after it was unable to reach its end goal of the Earth’s mantle – but it managed to tap into temperatures measuring 180 °C (356 °F) using traditional drilling technologies alone.

“Where conditions become too difficult for physical drill bits to operate, researchers have been testing the capabilities of directed energy beams to heat, melt, fracture and even vaporize basement rock in a process called spallation, before the drill head even touches it,” New Atlas recently reported.

Now, researchers are investigating other, more reliable ways to reach depths as great and greater than the Kola borehole, in order to make geothermal plants feasible for installation anywhere on the planet. Some projects have looked into borrowing technologies from the fracking industry to accomplish this goal. But so far this approach has not been fruitful, either as these technologies remain cost prohibitive. “For now, federal analysis shows this type of geothermal costs around $181 per megawatt hour, while utility-scale solar costs just $25,” NPR reported in 2023. However, some geothermal experts project that those costs will decrease by about a third over the next decade.

So now science has turned to poaching technology from an entirely different sector – nuclear fusion research. Gyrotrons are currently used in nuclear fusion experiments to super-heat and maintain plasma. But Quaise Energy, and MIT offshoot based in Cambridge, Mass., argues that they can also be used to drill deeper and more efficiently than ever before, by melting rock with energy beams. Quaise Energy has already raised $95 million from investors (including Mitsubishi) to apply gyrotrons to geothermal energy extractions.

The MIT team’s experimenting and mathematical models suggest that “a millimeter-wave source targeted through a roughly 20 centimeter waveguide could blast a basketball-size hole into rock at a rate of 20 meters per hour,” according to IEEE Spectrum. “At that rate, 25-and-a-half days of continuous drilling would create the world’s deepest hole.” Move over, Kola Superdeep Borehole.

This could have enormous ramifications for the future of energy as we know it, and a silver bullet for climate change to boot. “Barring too many further surprises, [gyrotron technology] should [...] significantly change the equation for ultra-deep drilling, making it possible and profitable to get deep enough into the crust to unlock some of the Earth's immense geothermal energy potential,” New Atlas reports.

By Haley Zaremba for Oilprice.com

German stellarator fusion design concept unveiled

Munich-based Proxima Fusion and its partners have published a new peer-reviewed paper presenting Stellaris, the world's first integrated concept for a commercial fusion power plant designed to operate reliably and continuously.

_46272.jpg)

Stellaris builds on the record-breaking results of the Wendelstein 7-X research experiment in Germany, the most advanced QI stellarator prototype in the world, directed by the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics (IPP) and the product of over EUR1.3 billion (USD1.4 billion) in funding from the German Federal Government and the European Union. In February 2023, Wendelstein 7-X succeeded for the first time in generating a high-energy plasma that lasted for eight minutes. The facility is designed to generate plasma discharges of up to 30 minutes in the coming years.

Published in Fusion Engineering and Design, Proxima Fusion - which was spun out of IPP in 2023 and was founded by a team which includes six former IPP scientists - says the Stellaris concept is "a major milestone for the fusion industry - advancing the case for quasi-isodynamic (QI) stellarators as the most promising pathway to a commercial fusion power plant".

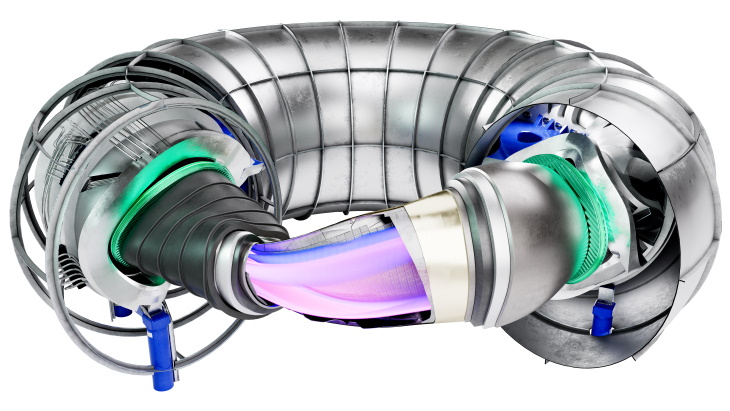

A stellarator fusion reactor is different to a tokamak fusion reactor such as the Joint European Torus in the UK or the ITER device under construction in France. A tokamak is based on a uniform toroid shape, whereas a stellarator twists that shape in a figure-8. This gets round the problems tokamaks face when magnetic coils confining the plasma are necessarily less dense on the outside of the toroidal ring.

(Image: Proxima Fusion)

According to Proxima Fusion, Stellaris is designed to produce much more power per unit volume than any stellarator power plant designed before. The much stronger magnetic fields that are enabled by high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnet technology allow for a significant reduction in size compared with previous stellarator concepts. It says smaller reactors can therefore be built more quickly, provide more efficient energy generation, and promise to be more cost-effective in both construction and operation. The Stellaris concept also makes use of only currently available materials, meaning it will be buildable by expanding on today's supply chains.

The company says its simulation-driven engineering approach has enabled rapid design iterations, leveraging advanced computing. Stellaris, it says, is the first QI stellarator-based power plant design that "simultaneously meets all major physics and engineering constraints, as demonstrated through electromagnetic, structural, thermal, and neutronic simulations".

Proxima Fusion says the Stellaris design incorporates groundbreaking technical features, including: a magnetic field design that obeys all key physics optimisation goals for energy production; support structures that can bear the forces present when operating at full power; a showcase that HTS technology can be effectively integrated in high field stellarators, while ensuring effective heat management on internal surfaces; and a neutron blanket concept that is adapted to the complex geometry of stellarators.

The company plans to demonstrate that stellarators are capable of net energy production with its demo stellarator Alpha in 2031, and aims to deliver fusion energy to the grid in the 2030s.

"The path to commercial fusion power plants is now open," said Francesco Sciortino, co-founder and CEO of Proxima Fusion. "Stellaris is the first peer-reviewed concept for a fusion power plant that is designed to operate reliably and continuously, without the instabilities and disruptions seen in tokamaks and other approaches."

"For the first time, we are showing that fusion power plants based on QI-HTS stellarators are possible," added Jorrit Lion, co-founder and chief scientist of Proxima Fusion. "The Stellaris design covers an unparalleled breadth of physics and engineering analyses in one coherent design. To make fusion energy a reality, we now need to proceed to a full engineering design and continue developing enabling technologies."

No comments:

Post a Comment