IN MEMORIAM

Media Matters host and journalism scholar Robert McChesney has died at 72

By Jim Meadows

March 28, 2025

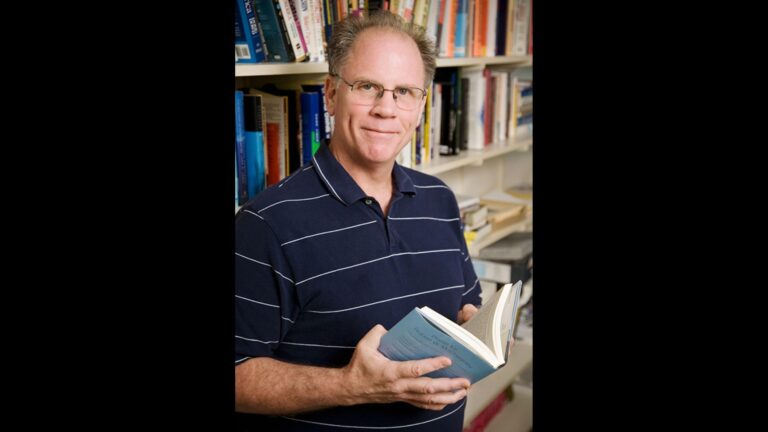

From 2002 to 2012, McChesney hosted the radio program Media Matters on Sunday afternoons on WILL-AM.

Photo: Courtesy/University of Illinois News Bureau

Robert W. McChesney, whose books and radio broadcasts denounced corporate domination of mass media, died this week at the age of 72 in Madison, Wisconsin.

From 2002 to 2012, the strains of Thelonius Monk’s “Straight No Chaser” opened McChesney’s radio programMedia MattersSunday afternoons on WILL-AM. TheUniversity of Illinois Communication professoroften hosted the one-hour program from Madison, where he had taught at the University of Wisconsin before coming to the U of I’s Communication Department.

Media Matters gave listeners the chance to hear and ask questions of some of the leading figures in left-wing and progressive politics. McChesney’s guests over the years included U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, the late former talk show host Phil Donahue, consumer advocate Ralph Nader, Democracy Now journalist and host Amy Goodman and the scholar and linguist Noam Chomsky.

McChesney’s ability to attract some of the best-known names in the progressive political world was likely possible because he was fairly well-known in that world himself.

He wrote, co-wrote or edited more than two dozen books. In titles such as “Rich Media, Poor Democracy” (2000) and “Digital Disconnect” (2014), McChesney argued that domination of the news media by a few large conglomerates threatened the democratic process. He claimed the result was a weakened news media that was unable to properly serve the public.

In a 2010 speech at the University YMCA in Champaign, subsequently aired on Media Matters, McChesney outlined his fears about the news media in the coming years.

“What we’ll have, though, is not a lack of news,” said McChesney. “We’re still going to have 24-channel news cycles. We’ll still have some semblance of newspapers. We’ll certainly have lots of what’s called news online. But we’ll have very precious little journalism. What we’ll have instead is a golden age of spin and propaganda.”

McChesney saw a role for the government to encourage more diversity in the news media. He argued that such a position was endorsed by America’s founders.

In a 2004 appearance on WILL-AM’s “Focus 580” program, McChesney noted that the federal government established low-cost postal rates for newspapers early on as a way to encourage a wide range of publications.

“The commitment to diversity that the founders had, it was self-interest to some extent,” he said. “Obviously, politicians want their own views to get favored. But I think there was a deep-seated understanding in the American people, as they participated in these debates, that having a diverse range of viewpoints was foundational to having a free society.”

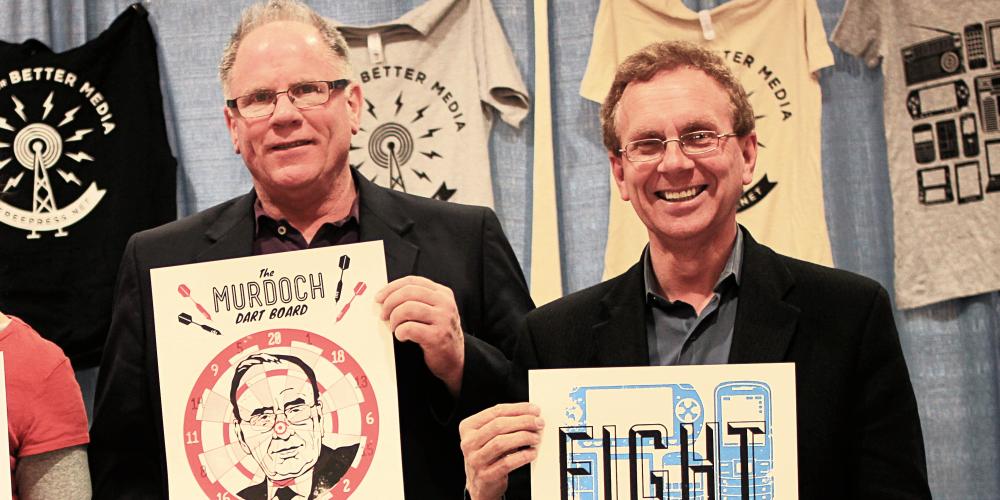

In 2003, McChesney helped co-foundthe media advocacy group Free Presswith journalist John Nichols of The Nation and activist Josh Silver. He served as one of the non-profit organization’s first presidents, leading Free Press to support net neutrality, press freedom, and the expansion of local journalism.

Ina news release noting his death, current Free Press president and co-CEO Craig Aaron said McChesney “opened the eyes of a generation of academics, journalists, politicians and activists — including me — to how media structures and policies shape our broader politics and possibilities.”

Inan obituary published in The Nation, John Nichols wrote that McChesney kept working in retirement, despite a series of health challenges, concluding with a year-long battle with cancer.

“His was a life fulfilled in the best sense of the word,” Nichols wrote of McChesney. “He died a happy man, holding the hand of his beloved wife, Inger Stole, and reflecting on time spent with his daughters, Amy and Lucy.”

Jim Meadows

Jim Meadows has been covering local news for WILL Radio since 2000, with occasional periods as local host for Morning Edition and All Things Considered and a stint hosting WILL's old Focus talk show. He was previously a reporter at public radio station WCBU in Peoria.

March 27, 2025

Timothy Karr,

WASHINGTON — Robert W. McChesney, the eminent media scholar and co-founder of Free Press, died on Tuesday, March 25, in Madison, Wisconsin. Before his retirement, McChesney was the Gutgsell Endowed Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he taught for two decades. He also taught from 1988 to 1998 at the University of Wisconsin. Among many other honors, he received lifetime-achievement awards from the International Communication Association and the Union for Democratic Communications.

McChesney was the author or editor of 27 books, including Rich Media, Poor Democracy; The Problem of the Media; and Digital Disconnect. He co-authored several books with his frequent co-author and close friend John Nichols, including The Death and Life of American Journalism and Dollarocracy. McChesney was the president of Free Press in its early years and served on its board of directors afterward.

Free Press President and Co-CEO Craig Aaron said:

“Bob McChesney was a brilliant scholar whose ideas and insights reached far beyond the classroom. He opened the eyes of a generation of academics, journalists, politicians and activists — including me — to how media structures and policies shape our broader politics and possibilities.

“While McChesney spent much of his career charting the problems of the media and the critical junctures that created our current crises, he believed fundamentally in the public’s ability to solve those problems and build a media system that serves people’s needs and sustains democracy. His ideas were bold and transformative, and he had little patience for tinkering around the edges. Rather than fighting over Washington’s narrow vision of what was possible, he always said — and Bob loved a good sports metaphor — that we needed to throw the puck down to the other end of the ice.

“McChesney believed in turning ideas into action — which is why he co-founded Free Press. He believed that people deserve a say in policy decisions that for far too long were made in their name but without their consent. He taught us that the media wasn’t something that just happened to us, but something that we can and must shape and change. We at Free Press remain committed to that work and his vision.

“McChesney was a generous mentor and devoted friend to me and so many others who made his cause our life’s work. While I was first moved by his words on the page, what I will remember most is his humor and kindness, his passion for the Cleveland Browns and Boston Celtics, and especially his devotion to his family. We send our deepest condolences to his wife, daughters and many friends. May his memory be a blessing.”

Learn More:

'The Crisis in Journalism Underpins a Crisis of Democracy'

The academic and activist inspired generations of people to challenge corporate power and support a media reform movement that lives on.

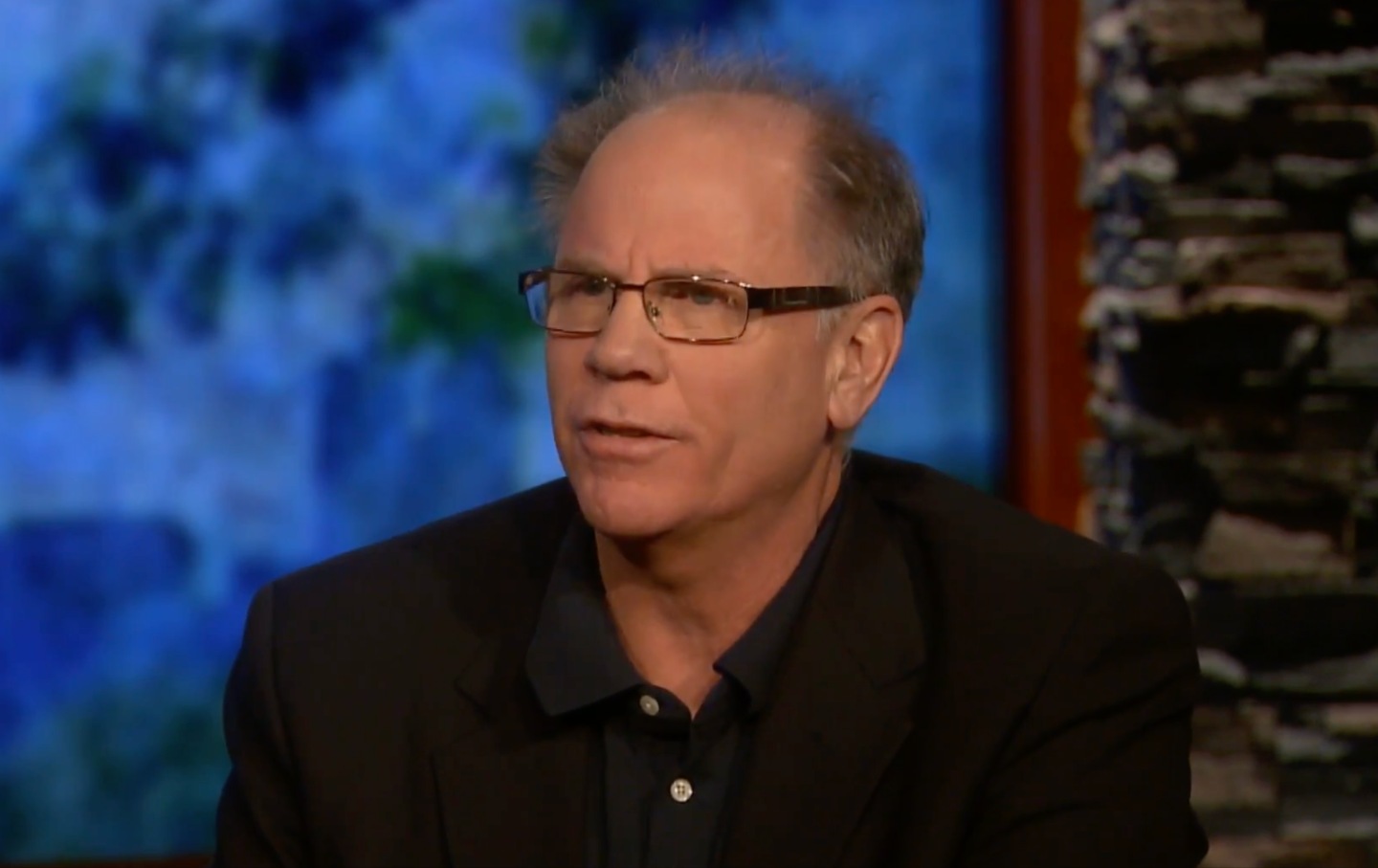

Bob McChesney on Moyers & Company in 2013.(Moyers & Company)

Bob McChesney, who died on Tuesday at the age of 72, first introduced himself to me almost 30 years ago, on the set of a public television news program in Madison, Wisconsin. Bob was a distinguished University of Wisconsin professor who was gaining an international reputation for his groundbreaking analysis of the threat to democracy posed by corporate control of media. Raising his arguments in books, speeches, and frequent C-Span appearances, he was well on his way to becoming one of the great public intellectuals of his time. I was a young newspaper editor who had earned a slim measure of recognition for my advocacy on behalf of investigative journalism and press freedom.

The program was framed as a debate about the future of journalism. Bob was positioned as the doomsayer, warning about how media consolidation was killing journalism. I was expected to counter that the future was actually bright. As it turned out, neither of us wanted to follow the script. Instead of arguing, we both agreed that profit-obsessed corporations were destroying American journalism, and that this destruction would pose an ever more serious threat to American democracy.

It wasn’t a particularly satisfying exchange for our hosts that evening, but it was the beginning of a collaboration that would span three decades. Bob and I cowrote half a dozen books and dozens of articles, joined Bill Moyers for a series of PBS interviews that would examine threats to journalism and democracy, and did our best, with more allies than we could have imagined in those early days, to stir up a reform movement that recognized the crisis and endeavored to set the stage for media that serves people rather than corporate bottom lines.

Bob, with his remarkable intellect and even more remarkable capacity for communicating his vision of a media that served citizens rather than corporations, was always the driving force. His research and his insatiable curiosity helped him to see the future more clearly than any scholar of his generation, with such precision that Moyers would compare him to both Tom Paine and Paul Revere. As new political and societal challenges arose in an ever more chaotic moment for America and the world, Bob explained how they should be understood as fresh manifestations of an ancient danger: the concentration of power—in this case, the power of the media, in the hands of old-media CEOs and new tech oligarchs, all of whom cared more about commercial and entertainment strategies than democratic and social values.

Bob took the “public” part of “public intellectual” seriously. You knew he wanted to swing into action when he’d say, “We need to put our heads together…” That was his call to write another book, organize another national conference on media reform, or rally another movement to defend the speak-truth-to-power journalism that the founders of the American experiment understood as the only sure footing for representative democracy.

Bob kept issuing the call, even as a series of health challenges slowed him down. He was still doing so a few days before his death following a year-long fight with cancer. His was a life fulfilled in the best sense of the word. He died a happy man, holding the hand of his beloved wife, Inger Stole, and reflecting on time spent with his daughters, Amy and Lucy.

Current Issue

April 2025 Issue

Our last conversations recalled friends and colleagues who had answered his calls to save journalism and renew our democracy: Craig Aaron, Victor Pickard, Josh Silver, Kimberly Longey, Russell Newman, Derek Turner, Ben Scott, Joe Torres, Tim Karr, Matt Wood, Katrina vanden Heuvel, Michael Copps, Noam Chomsky, Amy Goodman, Bernie Sanders, Ralph Nader, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, and too many others to name. Bob loved scholarship, loved activism, and loved collaborating with people who made connections between the two—sharing writing credits with former students at UW-Madison and later at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, working with unions of media workers and, perhaps above all, strategizing with the team at Free Press, the media reform group he cofounded in 2003 to advocate for diversity in ownership, robust public media, net neutrality and always, always, democracy. Bob was frustrated by the oligarchical overreach now on display in the Washington of Donald Trump and Elon Musk—a development he had predicted with eerie accuracy. Yet he remained undaunted to the end, still spinning out fresh ideas for upending corporate control of media, getting Big Money out of politics, and ushering in a new era of freewheeling debate and popular democracy.

That was the essence of Robert Waterman McChesney. He was a globally respected communications scholar who was wholly welcome in the halls of academia, yet he was never satisfied working within an ivory tower. He was a rigorous researcher into the worst abuse of corporate and political establishments. Yet he refused to surrender his faith in the ability of people-powered movements to upend monarchs and oligarchs and, in the words of Tom Paine, “begin the world over again.”

Bob regarded Paine—the immigrant pamphleteer who rallied the people of his adopted country to dismiss King George III and the colonial enterprise, and who spent the rest of his life demanding that this new United States live up to the egalitarian promise of liberty and justice for all—as the essential founder of the American project. Like Paine, Bob believed that with information and encouragement, grassroots activists could carry Paine’s legacy forward into the 21st century. Countless people heeded his call.

“Bob McChesney was a brilliant scholar whose ideas and insights reached far beyond the classroom. He opened the eyes of a generation of academics, journalists, politicians, and activists—including mine—to how media structures and policies shape our broader politics and possibilities,” explained Craig Aaron, the co-CEO of Free Press. “While McChesney spent much of his career charting the problems of the media and the critical junctures that created our current crises, he believed fundamentally in the public’s ability to solve those problems and build a media system that serves people’s needs and sustains democracy. His ideas were bold and transformative, and he had little patience for tinkering around the edges. Rather than fighting over Washington’s narrow vision of what was possible, he always said—and Bob loved a good sports metaphor—that we needed to throw the puck down to the other end of the ice.”

Bob examined the relationship between media and democracy with scholarly seriousness. Yet he coupled that seriousness with a penchant not just for sports metaphors and references to rock-and-roll songs but spot-on cinematic analogies, which invited Americans to recognize the crisis. Speaking to Moyers about how America’s media policies were forged behind closed doors in Washington, by lobbyists and politicians, Bob succintly defined that process: “Pure corruption. This is really where Big Money crowds everything else out. The way to understand how policymakers make media in this country [is to watch] a great movie: The Godfather: Part II. There’s a scene early in the movie where all the American gangsters are on top of a hotel roof in Havana. It’s a classic scene featuring Hyman Roth and Michael Corleone. They’ve got a cake being wheeled out to them. And Hyman Roth is cutting up slices of the cake. The cake’s got the outline of Cuba on it, and they’re giving each gangster a slice of Cuba. And while he’s doing this, Hyman Roth’s [talking about how they can work with government to carve up Cuba in ways that make them all rich]. That’s how media policy is made in the United States.”

The accessibility of his speech—the way it turned something as potentially obscure as communications policy into a readily understandable issue—was Bob’s genius. He wanted to upend the money power and tip the balance toward systems that would empower working-class people—as opposed to billionaires—to shape the future of media: with strategies for giving citizens democracy vouchers that they could use to support independent media, and a host of other remedies. Like his friend Bernie Sanders, Bob believed it essential to have a media free enough from corporate influence to speak truth to economic and political power, boldly critique the excesses of capitalism, and raise the alarm against creeping oligarchy.

This was the premise that underpinned an academic career that saw Bob author or co-author almost 30 books—including the groundbreaking Rich Media, Poor Democracy, his 1999 manifesto on how the decay of journalism would lead to a collapse of democratic norms, and 2013’s Digital Disconnect, his essential assessment of the danger of allowing Silicon Valley billionaires to define online communications. Many of the same themes ran through examinations of the shuttering of newspapers by corporate conglomerates that left communities as news deserts, of the destructive influence of political advertising on the national discourse, and of the failure of political and media elites to bring citizens into debates about automation, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. Noam Chomsky, whose own work on the media’s manufacturing of consent had profoundly influenced Bob’s scholarship (along with that of Ben Bagdikian, the journalist who wrote The Media Democracy), became Bob’s most ardent champion. “Robert McChesney’s work has been of extraordinary importance,” explained Chomsky. “It should be read with care and concern by people who care about freedom and basic rights.”

Bob’s research—and the books, lectures and activism that extended from it—earned him Harvard’s Goldsmith Book Prize, the Kappa Tau Alpha Research Award, the Newspaper Guild’s Herbert Block Freedom Award (for “having done more for press freedom than anyone”), and the International Communications Association’s C. Edwin Baker Award for the Advancement of Scholarship on Media, Markets and Democracy. It also gained him a hearing from thoughtful members of Congress, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Federal Trade Commission. Even if they did not always follow his advice, progressive officials recognized the wisdom of his analysis and incorporated it into their work. That’s one of the reasons why, in 2009, Utne Reader named Bob as one of “50 visionaries who are changing your world.” Charles Lewis, the founder of the Center for Public Integrity, simply referred to Bob as “the conscience of the media in America.”

Lewis wrote those words the better part of two decades ago. Bob remained that conscience, even as “media deserts” spread their arid path across America, as disinformation and misinformation overwhelmed the Internet, as propagandistic advertising warped our politics and as democratic expectations were undermined. It was all as he had predicted. But he was not inclined toward “I told you so” rejoinders.

Rather, Bob kept the faith that popular movements would push back against the decay, and the chaos, just as they had in the Progressive Era, the New Deal years, and the 1960s. “You’ve got to look in the mirror and understand that, if you act like change for the better is impossible, you guarantee it will be impossible,” he would say. “That’s the one decision each individual faces.”

Bob looked in that mirror confidently and courageously throughout a life of scholarship and activism. Some of our last conversations were about the huge crowds Bernie Sanders was attracting for his “Fighting Oligarchy” tour, and the thousands of Americans who have been showing up to challenge Republican members of Congress at town hall meetings. Just like Tom Paine, Bob saw fresh hope in the people who were rising up and demanding a future defined by their humanity, as opposed to corporate power. This might, he suggested, be the opening for a new surge in activism for journalism and democracy, a surge that might “begin the world over again.”

Bob’s last words to me, though they were a bit more labored due to his illness, were a repeat of his constant call to action: “Let’s put our heads together…” In other words, let’s make a plan. Let’s do something. That was his charge to those of us who cherished Bob McChesney’s mission and his spirit. We honor him best by accepting it.

John Nichols is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation. He has written, cowritten, or edited over a dozen books on topics ranging from histories of American socialism and the Democratic Party to analyses of US and global media systems. His latest, cowritten with Senator Bernie Sanders, is the New York Times bestseller It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism.

Robert W. McChesney, a Scholar/Activist Who Fought for Media Democracy

Media scholar Robert W. McChesney (1952-2025) pictured on the set of Moyers & Company in 2013. (Photo: Alton Christensen)

Bob was a scholar—the Gutgsell endowed professor of communications at University of Illinois—and a prolific author. Each and every book taught us more about corporate control of information. (I helped edit some of his works.)

Particularly enlightening was his 2014 book, Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning the Internet Against Democracy—in which McChesney explained in step-by-step detail how the internet that held so much promise for journalism and democracy was being strangled by corporate greed, and by government policy that put greed in the driver’s seat.

That was a key point for Bob in all his work: He detested the easy phrase “media deregulation,” when in fact government policy was actively and heavily regulating the media system (and so many other systems) toward corporate control.

For media activists like those of us at FAIR—whose board McChesney has served on for many years—it was a revelation to read his pioneering 1993 book Telecommunications, Mass Media and Democracy: The Battle for the Control of US Broadcasting, 1928–1935. It examined the broad-based movement in the 1920s and ’30s that sought to democratize radio, which was then in the hands of commercial hucksters and snake-oil salesmen.

From radio to the internet, a reading of his body of work offers a grand and inglorious tour of media history, and how we got to the horrific era of disinfotainment we’re in today.

Bob McChesney was not just a scholar. He was an activist. He co-founded the media reform group Free Press, with his close friend and frequent co-author John Nichols. Bob told me how glad he was to go door to door canvassing for Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns. (Bernie wrote the intro to one of McChesney and Nichols’ books.)

Bob was a proud socialist, and a proud journalist—and he saw no conflict between the two. In 1979, he was founding publisher of The Rocket, a renowned publication covering the music scene in Seattle. For years, while he taught classes, he hosted an excellent Illinois public radio show, Media Matters.

In 2011, he and Victor Pickard edited the book Will the Last Reporter Please Turn out the Lights: The Collapse of Journalism and What Can Be Done. One of Bob’s favorite proposals to begin to address the problem of US media (developed with economist Dean Baker) was to provide any willing taxpayer a voucher, so they could steer $200 or so of their tax money to the nonprofit news outlet of their choosing, possibly injecting billions of non-corporate dollars into journalism.

Bob was a beloved figure in the media reform/media activist movement. We need more scholar/activists like him today. He will be sorely missed.

Rich Media, Poor Democracy

Communication Politics in Dubious Times

Robert W. McChesney

Updated with a new preface by the author

A fifteenth-anniversary edition of the groundbreaking book on media conglomeration, reissued with a new preface from the celebrated media historian and author

“Robert W. McChesney is one of the nation’s most important analysts of the media.” —Howard Zinn

First published to great acclaim in 2000, Rich Media, Poor Democracy is Robert W. McChesney’s magnum opus. Called a “rich, penetrating study” by Noam Chomsky, the book is a meticulously researched exposition of how U.S. media and communication empires are threatening effective democratic governance. What happens when a few conglomerates dominate all major aspects of mass media, from newspapers and magazines to radio and broadcast television? Since the publication of this prescient work, which won Harvard’s Goldsmith Book Prize and the Kappa Tau Alpha Research Award, the concentration of media power and the resultant “hypercommercialization of culture” has only intensified.

McChesney lays out his vision for what a democratic society has the potential to become, offering compelling suggestions for how the media can be reformed as part of a broader program of democratic renewal. Rich Media, Poor Democracy remains as vital and insightful as ever and continues to serve as an important resource for researchers, students, and anyone who has a stake in the transformation of our digital commons.

This new edition includes a major new preface by McChesney in which he offers both a history of transformations in media since the book first appeared and a sweeping account of the organized efforts to reform the media system and the ongoing threats to our democracy as journalism has continued its sharp decline.

No comments:

Post a Comment