SPACE/COSMOS

China on Thursday launched its first space mission to retrieve samples from a nearby asteroid and conduct research back home, the Xinhua state news agency reported.

A successful completion of the mission could make China, a fast-growing space power, the third nation to get hold of the pristine asteroid rocks.

What do we know about the mission?

The mission began with a Long March-3B rocket carrying the Tianwen-2 probe blasting off from the Xichang launch site in southwestern Sichuan province at 1:31 a.m. local time (1731 GMT/UTC).

It took 18 minutes for the Tianwen-2 spacecraft to enter a transfer orbit for asteroid 2016HO3, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) said, according to Xinhua.

"The spacecraft unfolded its solar panels smoothly, and the CNSA declared the launch a success," the news agency wrote.

Tianwen-2 is scheduled to arrive at the asteroid in July 2026 and shoot a capsule packed with rocks back to Earth for a landing in November 2027.

The asteroid was discovered in 2016 by scientists in Hawaii and is roughly 40 to 100 metres (130-330 feet) in diameter and revolves relatively close to Earth.

The Tianmen-2 spacecraft is also tasked with exploring the comet 311P, according to the country's space agency.

China's 'space dream'

China has swiftly made its mark with its expanding space program.

In the past few years, it has poured billions of dollars into its space program to achieve what President Xi Jinping describes as the country's "space dream."

China already has its own space station, and in recent years, it has managed to send robots to the far side of the moon. It is now planning to send humans to the lunar surface by 2030.

What is driving China's space ambitions? 05:22

Edited by: Farah Bahgat

Midhat Fatimah Writer and reporter based in New Delhi

MISTRAL, a wind of change in the SRT observations

Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica

image:

The left panel shows the image of the nebula M42 taken at 90 GHz with the MISTRAL receiver. On the right, an overlay of the MISTRAL image with a wider-field image obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope

view moreCredit: MISTRAL commissioning team; NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

MISTRAL is a new generation receiver installed on the Sardinia Radio Telescope (SRT) and built by the Sapienza University of Rome for the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) as part of the upgrade of the radio telescope for the study of the Universe at high frequencies, funded by a PON (National Operational Program) project, concluded in 2023 and now providing its first significant scientific results. MISTRAL stands for “MIllimetric Sardinia radio Telescope Receiver based on Array of Lumped elements kids”.

MISTRAL is an innovative receiver in many ways. Radio astronomy receivers are typically "mono-pixel", i.e. sensitive to radiation coming from a single direction. Creating panoramic images of the area of the sky of interest requires long scans with the telescope. One way to overcome this limitation is to build "multi-pixel" receivers, i.e. sensitive to radiation coming from multiple directions simultaneously. MISTRAL takes this concept to the extreme. It contains an ultra-cold core composed of a matrix of 415 Kinetic Inductance Detectors (KIDs), developed in collaboration with CNR-IFN in Rome, and cooled to just a fraction of a degree above the temperature of absolute zero, or -273.15 degrees Celsius. "It is precisely this high number of detectors, combined with a specifically developed optical system, that makes MISTRAL an extremely effective and fast instrument for wide-field imaging of weak and extended sources", comments Paolo de Bernardis, Scientific Coordinator of the receiver for Sapienza University of Rome. MISTRAL was installed in May 2023 in the Gregorian focus, located at the center of the large 64-meter diameter SRT dish. Commissioning of the receiver began soon after and consisted of an intensive series of technical and observational tests aimed at integrating the receiver into the telescope system. A team of researchers from INAF and Sapienza have been working side by side with the aim of bringing MISTRAL to its maximum performance, and making it available to the scientific community for regular observations. “Commissioning”, explains Matteo Murgia, Scientific Manager of the receiver for INAF, “is normally a routine phase in the installation of new instrumentation. However, it becomes a real challenge in the case of a millimeter-wave receiver like MISTRAL, which requires the telescope’s performance to be pushed to the limit in every respect”.

“Initially, we faced and overcame several obstacles related to the truly exceptional cryogenics of the receiver, finally obtaining the temperature necessary for the activation of the KIDs, that is, just 0.2 degrees above absolute zero”, says Elia Battistelli, Project Manager of the receiver for Sapienza University of Rome.

Starting in September 2024, the improvement in the performance of the SRT active surface allowed us to reach the sensitivity required to calibrate the instrument. It was then possible to proceed with the optimization of the alignment between the MISTRAL optics and those of SRT.

The commissioning team also worked tirelessly to develop the procedures and software needed for pointing and focusing. At the same time, INAF and Sapienza developed the calibration and imaging procedures. MISTRAL was finally ready for “first light” observations of extended radio sources. Three iconic celestial objects were observed in succession: the Orion Nebula, the radio galaxy M87, and the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A. These observations highlighted MISTRAL’s remarkable versatility and confirmed its ability to produce highly detailed images of celestial objects in extremely diverse astrophysical contexts.

“The milestone achieved with the first light images of SRT at 90 GHz,” commented Isabella Pagano, Scientific Director of INAF, “marks an important step in broadening the scientific horizons of this radio telescope, thus demonstrating its ability to operate successfully at the high radio frequencies for which it was designed.” With the “first light” obtained by observing these fascinating cosmic objects, this first phase of technical tests is concluded and a no less important phase of scientific validation begins, aimed at verifying the performance of MISTRAL with increasingly weak sources, to ensure that it is ready for the numerous scientific challenges for which it was designed. MISTRAL will address a wide range of scientific questions, from cosmology and the physics of galaxy clusters, to the study of active galactic nuclei, the structure of molecular clouds and their relationship with star formation in nearby galaxies and the Milky Way, and the study of celestial bodies in our Solar System. The commissioning team's activities therefore continue, with the aim of verifying MISTRAL's performance in each of these scientific cases and making the receiver available to the scientific community as soon as possible.

Image of the radio source around M87 detected by MISTRAL at 90 GHz represented in red tones and contour lines, superimposed on an optical image, in blue tones, of the galaxy

Credit

MISTRAL commissioning team; Sloan Digital Sky Survey

Image of the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A taken at 90 GHz with the MISTRAL receiver.

Credit

MISTRAL commissioning team

The first images acquired by MISTRAL

In December 2024, MISTRAL was pointed at the famous Orion Nebula (also known as M42) in the center of the Orion constellation. Located about 1350 light-years from Earth, M42 is one of the closest active star-forming regions and is characterized by ionized hydrogen excited by a group of massive stars known as the Trapezium. M42 is part of a vast complex of molecular clouds that extends over 30 degrees across the sky, and MISTRAL observed its central part at an angular resolution of 12 arcseconds. The Orion Bar is clearly visible in the image to the south, marking a sharp boundary between the region of ionized hydrogen and the molecular cloud below. Emission peaks can also be seen near the stars of the Trapezium and the Kleinmann–Low Nebula, a dense star-forming molecular cloud that hosts a star cluster which underwent an explosive event in the past. The emission from M42 visible at 90 GHz is an almost equal mixture of radiation from ionized hydrogen and that from cold dust contained in the underlying molecular cloud complex.

In February 2025, MISTRAL observed the radio galaxy M87 in the constellation Virgo, whose active nucleus contains a now famous supermassive black hole, directly imaged thanks to the historic observation of the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019. The radio source surrounding M87 has a complex structure, made up of internal lobes measuring about thirty thousand light years (just over the distance that separates us from the center of the Milky Way) surrounded by an external plasma bubble on a larger scale. These structures are the result of the activity of the central black hole over the past several million years. The internal radio lobes are visible in MISTRAL's image – the most recent structures still powered by a pair of relativistic radio jets propagating from the central black hole. Observing these structures at such high frequencies provides new and valuable insights into the physical mechanisms powering the radio-emitting particles inside the source.

Finally, in the April 2025 session, MISTRAL observed – through two cross-scans of about half an hour each – the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (Cas-A), one of the most intense radio sources in the sky, with an angular size of about 5 arcminutes (about one-sixth the apparent diameter of the full Moon). The expanding gas shell is visible in its entirety and, thanks to the angular resolution of SRT at these wavelengths, it is possible to appreciate the details and brightness variations of the filamentary structure.

Behind the scenes on launch day for Biomass, ESA's latest mission | Euronews Tech Talks

What happens on a satellite's launch day? What are the thoughts and emotions of those behind the mission? Follow along with a special Euronews Tech Talks episode from Kourou.

In the early morning of April 29, people in Kourou, French Guiana, were woken up by the roar of the Vega-C rocket as it carried Biomass, the latest satellite from the European Space Agency (ESA), successfully into space.

The Biomass mission not only represents a leap forward in the scientific understanding of tropical forests, but its launch also marked a major step toward securing Europe’s independent access to space.

Euronews Tech Talks was on site in Kourou for the launch, and with this second special episode on Biomass, we bring you behind the scenes of the launch preparations.

A long journey

The operations on the day of the launch of a satellite, also referred to as D-Day, are just the tip of the iceberg in a long process to get it into space.

In the case of Biomass, the project started more than a decade ago and involved several professionals who dedicated their competencies to building the satellite, developing the rocket, and coordinating every step up to and after April 29.

Launch preparations began as early as March 7, when Biomass arrived in French Guiana after a two-week voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.

Upon arrival in Kourou, the satellite was transported to the spaceport, removed from its shipping container, and thoroughly inspected for any potential damage.

Next, Biomass was fuelled and attached to the adapter that would connect it to the Vega-C rocket, enabling its journey into orbit.

On April 14, Biomass was placed inside the fairing, the top part of the rocket, then transferred to the launch pad at the Tangara site.

There, the fairing containing the satellite was placed on the Vega C launcher, followed by more checks and a practice run known as the dress rehearsal.

With all checks completed, it was time for the first weather forecast, a crucial step in the process.

"We need good weather conditions to authorise the launch," explained Jean Frédéric Alasa, launch range operations director at CNES, the French Space Agency.

"The rain is not a major constraint, it’s more about the wind. If the launcher were to explode, we want to make sure the debris falls far from the populated areas," he continued.

Luckily, on April 29, the wind was very mild, and the satellite launch was authorised.

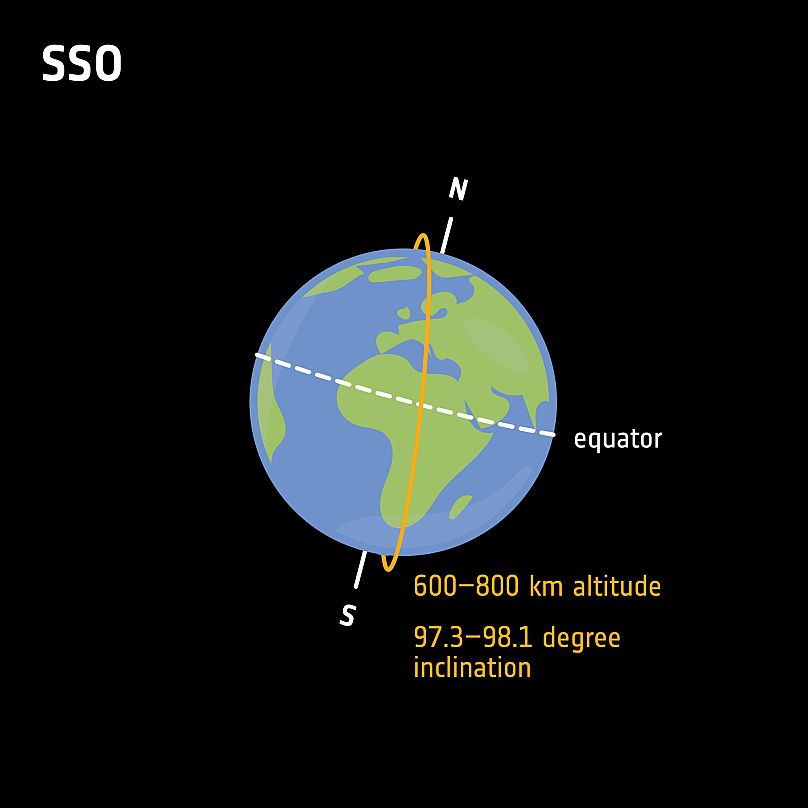

A sun-synchronous satellite

Vega C lifted off at 6:15:52 AM local time in Kourou. This time was precisely calculated and had to be respected to bring the satellite into the correct orbit.

"For all the SSO missions, there is no launch window, but just one time at which the satellite can be lifted off," Fabrizio Fabiani, head of the Vega programme at Arianespace, explained.

"Each day could be a good day, but at the same instant".

SSO stands for sun-synchronous orbit, a special type of orbit where the satellite maintains the same position relative to the Sun. Essentially, Biomass passes over the same location on Earth at the same time every day.

This orbit is ideal for monitoring changes over time, which is why it is commonly used for several Earth observation satellites.

An emotional moment

Biomass’s launch was successful and greeted with great excitement by those who worked on it for years.

When the satellite and rocket fully separated, the team erupted into cheers, celebrating the mission’s success.

"I've indeed been working for 12 years on that mission and now, at the end of it, I would say the predominant sentiment is that I'm super grateful and humbled that I was allowed to do that job," Michael Fehringer, ESA’s Biomass project manager, told Euronews.

"I feel relieved... that’s all we could ask for, that’s the best result we could have," Justin Byrne, Airbus head of science and Mars programmes, shared with us.

But while most celebrated, one team remained focused on the mission. Which team was it, and why?

Listen to Euronews Tech Talks to find out the answer.

No comments:

Post a Comment