Bhutan’s Pragmatic Pivot On Tibet – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy

In March 2025, the Chinese embassy in India, in collaboration with the government of Bhutan, organised Chinese New Year celebrations in Thimphu. Following the event, Bhutan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement referring to Tibet as the Xizang Autonomous Region.

The latest development comes at a time when China is facing increasing anxieties about Tibet—particularly the question of the Dalai Lama’s succession and its growing competition with the United States (US) and India. These concerns have shaped Beijing’s outreach to Bhutan over the past eight decades, and Thimphu, recognising that this time is no different, is bracing for the fallout with utmost pragmatism.

China’s Achilles Heel

Historically, Bhutan and Tibet have shared close cultural and historical ties, with the latter shaping Bhutan’s culture, political institutions, religion, and trade—even amidst political tensions and Tibetan interference in Bhutan’s internal affairs. Bhutan even maintained a representative in Lhasa until 1959 and paid annual tribute to Tibet. While Tibet claimed Bhutan as its tributary state and subordinate, there is little evidence of the same. After India’s independence, the Tibetan government communicated to New Delhi its claims—including some involving Bhutan, since India then guided Bhutan’s foreign policy. These assertions paved the way for China’s claims over Bhutan following the annexation of Tibet in 1950.

Following the annexation of Tibet, China began to share borders with Bhutan, with whom its borders had traditionally remained undemarcated. Initially, the Communist Party of China asserted that it would occupy Bhutan. However, later, Beijing toned its rhetoric down and claimed only specific territories within Bhutan. These claims emanated from two sources: Tibetan records and pasturelands used by Tibetan herdsmen. China followed a carrots-and-sticks approach, offering economic incentives even though it released multiple maps that claimed Bhutanese territories between the 1950s and 1960s. These claims, alongside the clampdown on practising Buddhists in Tibet, compelled Bhutan to cancel its trade engagements and withdraw its two officers from Tibet. Subsequently, it turned southward, developing a close and special relationship with India.

This tilt towards India further aggravated Beijing’s anxieties over Tibet and internal security. Some of these concerns were triggered by the US’s financing of the Tibetan rebellion, via Nepal, in the 1950s. Chinese responses have since been twofold: to further its internal hold over Tibet and pressurise Bhutan to close territorial disputes and open up diplomatic relations. This is driven by four calculations: one, to ensure Tibet is safe from separatism and infiltration. Second, to cut down on India’s influence as a regional player and undermine its influence in Bhutan, so that its security and status remain unchallenged. Third, to enforce its credentials as an Asian power, since Bhutan is the only neighbour of China with no diplomatic relations and the only country after India with a non-demarcated border. Fourth, to expand its territories and enhance offensive posturing against Bhutan and India.

Today, two key concerns confront China regarding Tibet: the Dalai Lama’s succession and escalating US-China tensions, exacerbated by growing India-US cooperation and their influence in neighbouring countries such as Nepal and Bhutan. The US’s Tibet Policy Acts of 2002, 2020, and 2024, and India’s hosting of the 14th Dalai Lama and many Tibetans have further fuelled Chinese apprehensions.

China’s latest white paper on national security underscores this paranoia of increasing external interference in the country, especially in the Tibet region. Since August 2023, Beijing has also expressed the need to use the ‘non-colonial’ term Xizang for Tibet in its official documents and references. This has helped Beijing further its legitimacy over Tibet and subsume the Tibetan identity within a Han-centric narrative. It has also urged other South Asian countries to refer to Tibet by its new name and to incorporate it into their one-China policy.

Undemarcated Borders: At the Heart of the Dispute

Chinese claims witnessed several discrepancies in the initial years. In 1958, China occupied over 300 square miles of Bhutanese territory, likely as part of its crackdown on the Tibetan rebellion. The following year, in 1959, its officials took over eight Bhutanese enclaves in Western Tibet and claimed the entire Tashigang area and the Doklam region.

Since 1984, China and Bhutan have held 25 rounds of negotiations to recognise and demarcate borders. These talks reduced the areas of disputed territory, from 1,128 sq km to 269 sq km in the western part of Bhutan. The disputed regions include: in the north, Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys; and in the west, Dramana and Shakhatoe, Sinchulungpa and Langmarpo valleys, Yak Chu and Charithang valleys, and the Doklam region.

As these discussions have prolonged, China’s anxieties over Tibet have increased its coercive actions. Since the 1990s, China has continued building roads and settlements in the disputed areas and encouraged Tibetan herders to graze in these regions and clashing with their Bhutanese counterparts. Since 2016, it has built over 22 villages and around 1,000 housing units in these disputed territories. Tibetans are given state subsidies and assistance to settle in these villages. In 2020, China even laid fresh claims to Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary (part of the Tashigang area), for the first time since the border negotiations began. In some cases, Beijing uses historical records to justify claims; in others, it creates “facts on the ground” through settlements and herders’ use of grazing lands—reinforcing its position, expanding territory, and pressuring Bhutan to accept the status quo during negotiations.

Assuaging Concerns: Bhutan’s Pragmatic Touch

Increasing Chinese pressure has compelled Bhutan to expedite border negotiations since 2020. In October 2023, China and Bhutan held the 25th round of boundary talks in Beijing, where they signed a cooperation agreement on the responsibilities and functions of the joint technical team (JTT) on border delimitation and demarcation. Both countries agreed to accelerate boundary demarcation and establish diplomatic relations during the discussions. During the meeting, Bhutan assuaged Chinese concerns and assured China that it firmly abides by the one-China principle (no specific reference was made to Tibet, though). In March 2024, a high-level Chinese delegation visited Bhutan to engage with the newly elected government. In August that year, they held the 14th Expert Group Meeting on boundary issues and the implementation of a cooperation agreement on the responsibilities and functions of JTT.

Bhutan has also assuaged Chinese concerns by historically maintaining distance from the Dalai Lama and excluding official contacts with Dharamsala. Even when accepting the refugees in the 1950s, the government was cautious that their loyalty to the Dalai Lama would create new internal challenges and external security issues vis-à-vis China. In 1979, the National Assembly asked the refugees to become Bhutanese citizens or leave the country. The number of Tibetan refugees has thus reduced from 6,300 to just 1,786. Furthermore, unlike previous generations, young Bhutanese are distanced from Tibet and are more welcoming of China. A recent survey reveals that young Bhutanese see China as a country with whom they enjoy cultural similarities and religious values, indicating how Tibet is a forgotten cause for several Bhutanese.

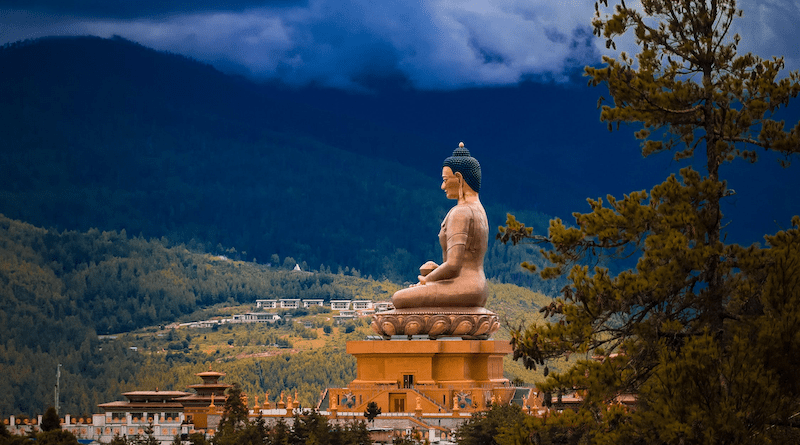

From the beginning of the century, Bhutanese monks and delegations have also undertaken visits to Tibet that were organised by China. In October 2023, a delegation from Bhutan also participated in China’s Rim of the Himalayas International Cooperation Forum. In March 2025, Thimphu even hosted a Chinese New Year event in collaboration with the Chinese government. The event saw the participation of the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Minister of Home Affairs, highlighting increasing interactions between the countries. Following the event, Bhutan, for the first time, referred to Tibet as the Xizang Autonomous Region. Furthermore, Bhutan’s economic difficulties and the need to attract Chinese investments—especially in its Gelephu Mindfulness City project—have motivated Thimphu to woo China. Thus, there is an increasinginterest in expanding engagements with Beijing and establishing bilateral ties between the countries.

This pragmatic policy towards Tibet is also likely to influence Bhutan’s response to the issue of the Dalai Lama’s succession. Thimphu realises that the issue of succession could open up multiple possibilities. The lack of global consensus would further Chinese anxieties and coercion, particularly in the case of a fallout between China and the US and India. There is also a possibility that China—with the help of the new Dalai Lama of their choice—could make new claims and justify them with exaggerated historical records. Thimphu thus realises its interests are in assuaging Beijing’s concerns, remaining indifferent to the issue of succession, and furthering its security and interests.

- About the author: Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy is an Associate Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation.

- Source: This article was published by the Observer Research Foundation.

Observer Research Foundation

ORF was established on 5 September 1990 as a private, not for profit, ’think tank’ to influence public policy formulation. The Foundation brought together, for the first time, leading Indian economists and policymakers to present An Agenda for Economic Reforms in India. The idea was to help develop a consensus in favour of economic reforms.

No comments:

Post a Comment