SPACE/COSMOS

Cosmic crime scene: White dwarf found devouring Pluto-like icy world

White dwarf offers rare glimpse of an icy extrasolar pluto-like world

University of Warwick

image:

Artists Impression of white dwarf WD 1647+375 accreting icy planetary fragments from a pluto-like world, creating the chemical signature idenfitifed in this study

view moreCredit: Snehalata Sahu/University of Warwick

University of Warwick astronomers have uncovered the chemical fingerprint of a frozen, water-rich planetary fragment being consumed by a white dwarf star outside our Solar System.

In our Solar System, it is thought that comets and icy planetesimals (small solid objects in space) were responsible for delivering water to Earth. The existence of these icy objects is a requirement for the development of life on other worlds, but it is incredibly difficult to identify them outside our Solar System as icy objects are small, faint and require chemical

In a study published in MRNAS, astronomers from Warwick, Europe and the US have found strong evidence that icy, volatile-rich bodies – capable of delivering water and the ingredients for life – exist in planetary systems beyond our own.

To make this discovery, the group used ultraviolet spectroscopy from the Hubble Space Telescope to study the chemical make-up of distant stars. One star, WD 1647+375, stood out as having ‘volatiles’ (chemical substances with low melting points) on the surface. White dwarf atmosphere is typically made up of hydrogen and helium, but WD 1647+375 had elements such as carbon, nitrogen, sulphur and oxygen.

This volatile-rich atmosphere was the first clue that WD 1647+375 was different.

Lead author Snehalata Sahu, Research Fellow, Department of Physics, University of Warwick said: “It is not unusual for white dwarfs to show signatures of calcium, iron and other metal from the material they are accreting (absorbing). This material comes from planets and asteroids that come too close to the star and are shredded and accreted. Analysing the chemical make-up of this material gives us a window into how planetesimals outside the Solar System are composed.

“In this way, white dwarfs act like cosmic crime scenes — when a planetesimal falls in, its elements leave chemical fingerprints in the star’s atmosphere, letting us reconstruct the identity of the ‘victim’. Typically, we see evidence of rocky material being accreted, such as calcium and other metals, but finding volatile-rich debris has been confirmed in only a handful of cases.”

One volatile - nitrogen - is a particularly important chemical fingerprint of icy worlds. The ultraviolet spectroscopy in this study showed that the material gained by WD 1647+375 had a high percentage of its mass as nitrogen (~5%). This is the highest nitrogen abundance ever detected in a white dwarf’s debris. The atmosphere of WD 1647+375 had also gained much more oxygen than would be expected if the object being absorbed was rock - 84% more, both suggesting an icy object.

The astronomers also had data to show that the debris had been feeding the star for at least the last 13 years, at a rate of 200,000 kg (the weight of an adult blue whale) per second. This meant that the icy object was at least 3km across (or comet sized), but this is a minimum size as accretion can take hundreds of thousands of years more than this 13-year snapshot, meaning the object could be closer to 50km in diameter and a quintillion kilograms.

Together, the data painted a picture of an icy/water-rich planetesimal (made up of 64% water) that was being consumed by this star, perhaps a comet like Halley’s or a dwarf planet fragment like C/2016 R2.

Second author Professor Boris T. Gänsicke, Department of Physics, University of Warwick said: “The volatile-rich nature of WD 1647+375 makes it like Kuiper-belt objects (KBOs) in our solar system - the icy objects found beyond the orbit of Neptune. We think that the planetesimal being absorbed by the star is most likely a fragment of a dwarf planet like Pluto. This is based on its nitrogen-rich composition, the high predicted mass and the high ice-to-rock ratio of 2.5, which is more than typical KBOs and likely originates from the crust or mantle of a Pluto-like planet.”

This is the first unambiguous finding of a hydrogen-atmosphere white dwarf purely absorbing an icy planetesimal. Whether this object formed in the planetary system around the original star or is instead an interstellar comet captured from deep space, remains an open question. Either way, the finding provides compelling evidence that icy, volatile-rich bodies exist in planetary systems beyond our own.

The discovery also highlights the unique role of ultraviolet spectroscopy in probing the composition of such rare volatile-rich objects beyond our Solar System. Only UV can detect the volatile elements (carbon, sulphur, oxygen, and especially nitrogen) and will be an important part of future attempts to search for the building blocks of life around other stars.

ENDS

Notes to Editors

For more information please contact:

Matt Higgs, PhD | Media & Communications Officer (Press Office)

Email: Matt.Higgs@warwick.ac.uk | Phone: +44(0)7880 175403

About the University of Warwick

Founded in 1965, the University of Warwick is a world-leading institution known for its commitment to era-defining innovation across research and education. A connected ecosystem of staff, students and alumni, the University fosters transformative learning, interdisciplinary collaboration and bold industry partnerships across state-of-the-art facilities in the UK and global satellite hubs. Here, spirited thinkers push boundaries, experiment and challenge convention to create a better world.

Journal

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Discovery of an icy and nitrogen-rich extra-solar planetesimal

Article Publication Date

18-Sep-2025

New Mars research reveals multiple episodes of habitability in Jezero Crater

Rice University

image:

Rice University graduate student Eleanor Moreland (Credit: Brandon Martin/Rice University).

view moreCredit: Brandon Martin/Rice University.

New research using NASA’s Perseverance rover has uncovered strong evidence that Mars’ Jezero Crater experienced multiple episodes of fluid activity — each with conditions that could have supported life.

By analyzing high-resolution geochemical data from the rover, scientists have identified two dozen types of minerals, the building blocks of rocks, that help reveal a dynamic history of volcanic rocks that were altered during interactions with liquid water on Mars. The findings, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, provide important clues for the search for ancient life and help guide Perseverance’s ongoing sampling campaign.

The study was led by Rice University graduate student Eleanor Moreland and employed the Mineral Identification by Stoichiometry (MIST) algorithm — a tool developed at Rice — to interpret data from Perseverance’s Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry (PIXL). PIXL bombards Martian rocks with X-rays to reveal their chemical composition, offering the most detailed geochemical measurements ever collected on another planet, according to the study.

“The minerals we find in Jezero using MIST support multiple, temporally distinct episodes of fluid alteration,” Moreland said, “which indicates there were several times in Mars’ history when these particular volcanic rocks interacted with liquid water and therefore more than one time when this location hosted environments potentially suitable for life.”

Minerals form under specific environmental conditions of temperature, pH and the chemical makeup of fluids, making them reliable storytellers of planetary history. In Jezero, the 24 mineral species reveal the volcanic nature of Mars’ surface and its interactions with water over time. The water chemically weathers the rocks and creates salts or clay minerals, and the specific minerals that form depend on environmental conditions. The identified minerals in Jezero reveal three types of fluid interactions, each with different implications for habitability.

The first suite of minerals — including greenalite, hisingerite and ferroaluminoceladonite — indicate localized high-temperature acidic fluids that were only found in rocks on the crater floor, which are interpreted as some of the oldest rocks included in this study. The water involved in this episode is considered the least habitable for life, since research on Earth has shown high temperatures and low pH can damage biological structures.

“These hot, acidic conditions would be the most challenging for life,” said co-author Kirsten Siebach, assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Rice. “But on Earth, life can persist even in extreme environments like the acidic pools of water at Yellowstone, so it doesn’t rule out habitability.”

The second suite of minerals reflects moderate, neutral fluids that support more favorable conditions for life and were present over a larger area. Minerals like minnesotaite and clinoptilolite formed at lower temperatures and neutral pH with minnesotaite detected in both the crater floor and the upper fan region, while clinoptilolite was restricted to the crater floor.

Finally, the third category represents low-temperature, alkaline fluids and is considered quite habitable from our modern Earth perspective. Sepiolite, a common alteration mineral on Earth, formed under moderate temperatures and alkaline conditions and was found widely distributed across all units the rover has explored. The presence of sepiolite in all of these units reveals a widespread episode of liquid water creating habitable conditions in Jezero crater and infilling sediments.

“These minerals tell us that Jezero experienced a shift from harsher, hot, acidic fluids to more neutral and alkaline ones over time — conditions we think of as increasingly supportive of life,” Moreland said.

Because Mars samples can’t be prepared or scanned as precisely as Earth samples, the team developed an uncertainty propagation model to strengthen its results. Using a statistical approach, MIST repeatedly tested mineral identifications considering the potential errors, similar to how meteorologists forecast hurricane tracks by running many models.

“Our error analysis lets us assign confidence levels to every mineral match,” Moreland said. “MIST not only informs Mars 2020 science and decision-making, but it is also creating a mineralogical archive of Jezero Crater that will be invaluable if samples are returned to Earth.”

The results confirm that Jezero — once home to an ancient lake — experienced a complex and dynamic aqueous history. Each new mineral discovery not only brings scientists closer to answering whether Mars ever supported life but also sharpens Perseverance’s strategy for which samples to collect and return.

This publication provides a thorough compilation of minerals identified using the MIST model for the first three years of Perseverance’s mission. While it does not include the specific sampling site presented in the press release about detection of a potential biosignature, this work provides context for how the habitable conditions observed for that sample, Sapphire Canyon, were present more broadly in Jezero. This context-setting information is key to any interpretation of the potential biosignatures that were identified.

This research was supported by Mars 2020 Participating Scientist grants, JPL, the Mars 2020 PIXL team, the Mars 2020 Returned Sample Science Participating Scientist program and NASA’s Mars Exploration Program.

Kirsten Siebach, assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Rice University (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University).

Article Title

Multiple Episodes of Fluid Alteration in Jezero Crater Indicated by MIST Mineral Identifications in PIXL XRF Data From the First 1100 Sols of the Mars 2020 Mission

SwRI, UT San Antonio will test technology designed to support extended space missions to Moon, Mars

Researchers will evaluate novel electrolyzer in reduced gravity aboard parabolic flights

video:

The University of Texas at San Antonio and Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) will flight test novel electrolyzer technology to characterize its performance and associated bubble dynamics in low gravity. In this video, an electrochemical cell filled with simulated Martian brine recreates the processes that produce oxygen and hydrocarbon consumables.

view moreCredit: Southwest Research Institute/UTSA

SAN ANTONIO —September 17, 2025 — Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and The University of Texas at San Antonio (UT San Antonio) will flight test novel electrolyzer technology to better understand chemical processes associated with bubble formation in low gravity. Designed to solve future space mission challenges, the project, led by SwRI’s Kevin Supak and UT San Antonio’s Dr. Shrihari Sankarasubramanian, is supported by a $125,000 grant from the Connecting through Research Partnerships (Connect) program, which fosters collaboration between the two institutions. It is also supported by the university’s Klesse College of Engineering and Integrated Design (KCEID) and the Center for Space Technology and Operation Research (CSTOR).

“Extended space missions will require in situ resource utilization to produce chemicals and consumables. These processes will yield gas and liquid interactions within the technology,” Supak said. “A partial gravity environment, like that of the Moon or Mars, has a reduced buoyancy effect on gas bubbles, which can pose challenges to surfaces that must remain wetted with liquid to function.”

SwRI and UT San Antonio will evaluate the performance of a patent-pending electrolyzer, the Mars Atmospheric Reactor for Synthesis of Consumables (MARS-C), in simulated partial gravity environments. Developed with NASA support by Sankarasubramanian, MARS-C is meant to improve production of propellants and life-support compounds on the Moon, Mars or near-Earth asteroids.

MARS-C is designed to use local resources on the Moon or Mars to produce fuel, oxygen and other life support compounds necessary for long-term human habitation. It applies voltage across two electrodes to electrochemically convert simulated Martian brine and carbon dioxide into methane, oxygen and other hydrocarbons.

The researchers will integrate MARS-C into an existing SwRI-built flight rig and test it aboard a series of parabolic flights, which fly in a series of arcs to create periods of freefall, simulating weightlessness. This approach builds on previous work conducted by SwRI that studied boiling processes under partial gravity aboard parabolic flights. SwRI’s research showed that lower gravity affects surface bubble dynamics, which can, in turn, affect gas production rates.

Earlier this year, Supak and Sankarasubramanian received the NASA’s TechLeap prize in support of flight testing MARS-C. The Connect grant allows them to significantly expand the scope of their project.

“With Connect’s support, we can study additional variables, including the effects of temperature conditions similar to Mars and the Moon,” Supak said. “We’ll also examine how the electrodes’ surface textures, material properties and spacing within the cell affect bubble nucleation.”

The grant will also support more comprehensive testing and advanced instrumentation, including high-speed video recording to capture how gas bubbles form inside the cells during parabolic flight. The flights are currently scheduled for 2026.

“Ultimately, this project helps address a major civil space shortfall that NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate has identified,” said Sankarasubramanian. “Technology demonstration under relevant gravity conditions is much harder to do compared to simulating temperature, pressure or gas compositions of other planets – we are doing that and significantly advancing this system up NASA’s Technology Readiness Level (TRL) chain.”

SwRI’s Executive Office and the UT San Antonio Office of Research sponsor the Connect program, which offers grant opportunities to enhance greater scientific collaboration between the two institutions. This project’s funding is supported by UT San Antonio’s Klesse College of Engineering and Integrated Design (KCEID) and the Center for Space Technology and Operation Research (CSTOR).

For more information, visit https://www.swri.org/markets/energy-environment/oil-gas/fluids-engineering/fluid-physics-space-applications.

XRISM uncovers a mystery in the cosmic winds of change

image:

Artist’s impression of the powerful winds blowing from the bright X-ray source GX13+1. The X-rays are coming from a disc of hot matter, known as an accretion disc, that is gradually spiralling down to strike a neutron star’s surface.

view moreCredit: ESA

The X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM) has revealed an unexpected difference between the powerful winds launching from a disc around a neutron star and those from material circling supermassive black holes. The surprisingly dense wind blowing from the stellar system challenges our understanding of how such winds form and drive change in their surroundings.

On 25 February 2024, XRISM used its Resolve instrument to look at neutron star GX13+1, the burnt-out core of a once larger star. GX13+1 is a bright X-ray source. The X-rays are coming from a disc of hot matter, known as an accretion disc, that is gradually spiralling down to strike the neutron star’s surface.

Such inflows also power outflows that influence and transform the cosmic environment. Yet the details of how these outflows are produced remain a matter of ongoing research. This is why XRISM was observing GX13+1.

Given the unprecedented power of Resolve to tease out the energy of incoming X-ray photons, the XRISM team expected to see those details as never before.

"When we first saw the wealth of details in the data, we felt we were witnessing a game-changing result," says Matteo Guainazzi, ESA XRISM project scientist. "For many of us, it was the realisation of a dream that we had chased for decades.”

Such cosmic winds are much more than scientific curiosities – they are the winds that drive cosmic change.

They appear also from supermassive black holes systems found at the centres of galaxies, and can cause stars to form by triggering the collapse of giant molecular clouds, or they can stop star formation by heating and blowing those clouds apart. Astronomers call this ‘feedback’, and it can be so powerful that the winds from a supermassive black hole can control the growth of its entire parent galaxy.

Since the mechanisms generating the winds from supermassive black holes may be fundamentally the same as those at work around GX13+1, the team chose to look at GX13+1 because it is closer and therefore appears brighter than the supermassive black hole varieties, meaning that it can be studied in more detail.

There was a surprise. A few days before their observations were due to take place, GX13+1 unexpectedly got brighter – reaching or even exceeding a theoretical ceiling known as the Eddington limit.

The principle behind this limit is that as more matter falls onto a compact object such as a black hole or a neutron star, more energy is released. The faster energy is released, the greater the pressure it exerts on other infalling material, pushing more of it back into space. At the Eddington limit, the amount of high-energy light being produced is essentially enough to transform almost all of the infalling matter into a cosmic wind.

And Resolve happened to be watching GX13+1 as this staggering event took place.

"We could not have scheduled this if we had tried," said Chris Done, Durham University, UK, the lead researcher on the study. "The system went from about half its maximum radiation output to something much more intense, creating a wind that was thicker than we'd ever seen before."

But mysteriously, the wind was not travelling at the speed that the XRISM scientists were expecting. It remained around 1 million km/h. While fast by any terrestrial standard, this is decidedly sluggish when compared to the cosmic winds produced near the Eddington limit around a supermassive black hole. In that situation, the winds can reach 20 to 30 percent the speed of light, more than 200 million km/h.

“It is still a surprise to me how ‘slow’ this wind is,” says Chris, “as well as how thick it is. It’s like looking at the Sun through a bank of fog rolling towards us. Everything goes dimmer when the fog is thick.”

It was not the only difference the team observed. XRISM had earlier revealed a wind from a supermassive black hole at the Eddington limit. There the wind was ultrafast and clumpy, whereas the wind in GX13+1 is slow and smooth flowing.

“The winds were utterly different but they're from systems which are about the same in terms of the Eddington limit. So if these winds really are just powered by radiation pressure, why are they different?” asks Chris.

The team has proposed that it comes down to the temperature of the accretion disc that forms around the central object. Counterintuitively, supermassive black holes tend to have accretion discs that are lower in temperature than those around stellar mass binary systems with black holes or neutron stars.

This is because the accretion discs around supermassive black holes are larger. They are also more luminous, but their power is spread across a larger area – everything is bigger around a big black hole. So, the typical kind of radiation released by a supermassive black hole accretion disc is ultraviolet, which carries less energy than the X-rays released by the stellar binary accretion discs.

Since ultraviolet light interacts with matter much more readily than X-rays do, Chris and her colleagues speculate that this may push the matter more efficiently, creating the faster winds observed in black hole systems.

If so, the discovery promises to reshape our understanding of how energy and matter interact in some of the most extreme environments in the Universe, providing a more complete window into the complex mechanisms that shape galaxies and drive cosmic evolution.

“The unprecedented resolution of XRISM allows us to investigate these objects – and many more –in far greater detail, paving the way for the next-generation, high-resolution X-ray telescope such as NewAthena,” says Camille Diez, ESA Research fellow.

Notes for editors

‘Multi-phase winds from a super-Eddington X-ray binary are slower than expected’ by the XRISM collaboration appears online in Nature on 17 September 2025 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09495-w

XRISM (pronounced krizz-em) was launched on 7 September 2023. It is a mission led by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) in partnership with NASA and ESA. It carries two instruments: an X-ray calorimeter called Resolve capable of measuring the energy of individual X-ray photons to produce a spectrum at unprecedented level of ‘energy resolution’ (the capability of an instrument to distinguish the X-ray ‘colours’), and a large field-of-view X-ray CCD camera to image the surrounding field called Xtend.

XRISM is performing high-resolution X-ray spectroscopic observations of the hot gas plasma wind that blows through the galaxies in the universe. This innovative, JAXA-led international project is developed in collaboration with NASA, ESA, and other highly-qualified partners.

Credit

JAXA

Journal

Nature

Method of Research

Observational study

Article Title

Stratified wind from a super-Eddington X-ray binary is slower than expected

Article Publication Date

17-Sep-2025

Mars’s chilly north polar vortex creates a seasonal ozone layer

image:

A schematic of temperature measurements shows how it is 40 degrees Celsius colder inside the north polar vortex (indicated by the yellow line) compared to outside the vortex.

view moreCredit: Kevin Olsen (University of Oxford) et al.

A rare glimpse into the wintry conditions of Mars’s north polar vortex has shown that temperatures inside the vortex are far colder than outside, and that the permanent darkness that winter brings to the martian north pole facilitates a surge in ozone in the atmosphere.

“The atmosphere inside the polar vortex, from near the surface to about 30 kilometres high, is characterised by extreme cold temperatures, about 40 degrees Celsius colder than outside the vortex,” said Dr Kevin Olsen of the University of Oxford, who presented the results at the EPSC-DPS2025 Joint Meeting in Helsinki last week.

At such frigid temperatures, what little water vapour there is in the atmosphere freezes out and is deposited onto the ice cap, but this leads to consequences for ozone in the vortex. Ordinarily ozone is destroyed by reacting with molecules produced when ultraviolet sunlight breaks down water vapour. However, with all the water vapour gone, there’s nothing for the ozone to react with. Instead, ozone is able to accumulate within the vortex.

“Ozone is a very important gas on Mars – it’s a very reactive form of oxygen and tells us how fast chemistry is happening in the atmosphere,” said Olsen. “By understanding how much ozone there is and how variable it is, we know more about how the atmosphere changed over time, and even whether Mars once had a protective ozone layer like on Earth.”

The European Space Agency’s ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover, which is currently scheduled to launch in 2028, will search for evidence of past life on Mars. The possibility that Mars once had an ozone layer protecting the planet’s surface from the deadly influx of ultraviolet radiation from space would boost the chances that life could have survived on Mars billions of years ago substantially.

How Mars’s Polar Vortex Forms

The polar vortex is a consequence of Mars’s seasons, which occur because the Red Planet’s axis is tilted at an angle of 25.2 degrees. Just like on Earth, the end of northern summer sees an atmospheric vortex develop over Mars’s north pole and last through to the spring.

On Earth the polar vortex can sometimes become unstable, lose its shape and descend southwards, bringing colder weather to the mid-latitudes. The same can happen to Mars’s polar vortex, and in doing so it provides an opportunity to probe its interior.

“Because winters at Mars’s north pole experience total darkness, like on Earth, they are very hard to study,” says Olsen. “By being able to measure the vortex and determine whether our observations are inside or outside of the dark vortex, we can really tell what is going on.”

Probing the Vortex

Olsen works with ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter that is in orbit around Mars. In particular, the spacecraft’s Atmospheric Chemistry Suite (ACS) studies Mars’s atmosphere by gazing at the Red Planet’s limb when the Sun is on the other side of the planet and is shining through the atmosphere. The wavelengths at which the sunlight is absorbed give away which molecules are present in the atmosphere and how high above the surface they are.

However, this technique doesn’t work during the total darkness of martian winter when the Sun doesn’t rise over the north pole. The only opportunities to glimpse inside the vortex are when it loses its circular shape but, to know exactly when and where this is happening, requires additional data.

For this, Olsen turned to the Mars Climate Sounder instrument on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to measure the extent of the vortex via temperature measurements.

“We looked for a sudden drop in temperature – a sure sign of being inside the vortex,” said Olsen. “Comparing the ACS observations with the results from the Mars Climate Sounder shows clear differences in the atmosphere inside the vortex compared to outside. This is a fascinating opportunity to learn more about martian atmosphere chemistry and how conditions change during the polar night to allow ozone to build up.”

A view of the north pole of Mars, created by taking images as seen by the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft and applying topographic data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter that was on board NASA’s now defunct Mars Global Surveyor mission.

Credit

ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/NASA MGS MOLA Science Team.

3I/ATLAS And Oumuamua: Comets Or Alien Technology? – Analysis

Interstellar object 3I/ATLAS imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Could similar objects be the seeds of new planets around young stars? CREDIT: NASA/ESA/David Jewitt (UCLA). Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI).

By Observer Research Foundation

By Prateek Tripathi

In the midst of sporadic speculations regarding the exact nature of Oumuamua, our solar system was visited by yet another interstellar guest recently, 3I/ATLAS. Possessing unusual properties not too dissimilar to the former, the sighting of 3I/ATLAS has brought various lingering theories back into the spotlight — ranging from more grounded ideas like dark comets to hyperbolic explanations like alien probes and Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAPs).

Though the idea of UAPs may sound exaggerated, the bizarre characteristics associated with these objects certainly seem to warrant unconventional theories. That being said, the exact nature of these interstellar objects (ISOs) remains largely unknown, a situation likely to be remedied in the future, thanks to the increasing number of initiatives planned to address the issue. This will not only shed further light on ISOs but may also address multiple issues plaguing cosmology. Moreover, due to their unpredictable behaviour and trajectories, ISOs also serve to reiterate the importance of planetary defence, an issue garnering increasing global attention in recent years.

Oumuamua and Borisov: A New Class of Celestial Objects

On October 19, 2017, the Pan-STARRS1 telescope at the University of Hawaii detected a unique objectblazing through our solar system. As part of NASA’s Near-Earth Object Observations (NEOO) Programme, the telescope’s objective is to find, classify, and track celestial objects, including comets and asteroids. Though initially classified as a comet, the object started garnering increasing attention amongst the astronomical community on account of its unique characteristics, and was subsequently named “Oumuamua,” the Hawaiian term for scout.

First, it was uniquely elongated, with its length (400 metres) being almost ten times its width. Second, it was found travelling at an extremely high velocity, reaching a maximum speed of about 87.3 km/s(kilometres per second), a property very uncharacteristic of objects originating within our solar system. Last, it did not possess a coma or tail, which are characteristic features of comets, resulting from the melting of ice, water, and other constituent gases when warmed by the Sun, causing them to accelerate as they move away from it. Yet, Oumuamua was found to be accelerating as it moved away from the Sun despite the fact that it possessed no such tail, sparking discussion and debate among cosmologists as to the exact reason behind this buildup of speed. This also led to widespread speculation that the object may, in fact, be an alien probe or spaceship, which would explain this supposedly spontaneous non-gravitational acceleration.

Further observations and studies revealed Oumuamua to be the first known ISO to be observed within our solar system. While several theories have been proposed to rationalise its behaviour, an exact explanation remains elusive. For instance, according to one proposed explanation, as ISOs get bombarded by high-energy particles such as cosmic rays, the ice within them produces hydrogen, which is subsequently trapped inside. As the ISO reaches closer to the Sun, the trapped hydrogen is released, and the object is accelerated due to this outgassing. However, according to other studies, it seems quite likely that cosmic ray reactions with simple molecules create more complex molecules such as amino acids and not simpler ones like hydrogen, casting the explanation into doubt. There are other examples of such “dark comets” within our solar system, though the cause behind their acceleration is also not very well understood at the moment.

Subsequently, on August 30, 2019, a second ISO, the “2I/Borisov,” was detected by a Crimean amateur astronomer. However, unlike Oumuamua, the Borisov appeared more similar to a regular comet, possessing a bright nucleus surrounded by dust, though it was found to be travelling at an incredibly high velocity of about 30 km/s. It is still a mystery as to why the two ISOs are so fundamentally different in nature, though this is most likely a consequence of their orbital histories and origins.

3I/ATLAS

On July 1, 2025, the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) survey telescope in Chile reported the discovery of a third ISO, now designated “3I/ATLAS” by NASA’s Minor Planet Center. It has been categorised as an ISO because, unlike comets originating within the solar system, which follow a closed orbital path around the Sun, 3I/ATLAS follows a hyperbolic trajectory (with a highly eccentric orbit), implying that it is not bound by the Sun’s gravity. Additionally, the comet exhibits some remarkable properties distinguishing it from its predecessors.

First, the eccentricity of its orbit is much higher than that of either Oumuamua or Borisov. Moreover, 3I/ATLAS seems to be much larger, possessing a width of over 20 km. However, it is similar to Borisov in the sense that it has been confirmed to be a comet, due to its characteristic coma and tail, though there are some cosmologists who argue that the object may be composed of alien technology due to its unusual trajectory and tilt.

Figure 1: 3I/ATLAS Trajectory

Regardless of its exact nature, 3I/ATLAS will remain visible through September 2025, after which it will reach its closest approach to the Sun of about 1.4 astronomical units (210 million km) around October 30, making it difficult to observe. Thereafter, it will remerge on the Sun’s opposite side in December, making further observations possible. Although 3I/ATLAS’s enormous velocity makes it impossible to physically intercept it (via spacecraft or other means), its relatively early detection as compared to its predecessors will enable an unprecedented level of observation and analysis, thereby shedding more light on the exact nature of ISOs and their chemical composition.

Future Cosmological and Strategic Implications

Though there is an abundance of ISOs in the Milky Way, their detection has remained elusive due to a multitude of reasons. They are usually quite small and travel with huge velocities, making them particularly hard to detect since it is not possible to determine their initial trajectory before they enter the solar system, nor their exact time of arrival, given that most of them are on long-period orbits ranging from hundreds to thousands of years. Furthermore, ISOs do not appear to pass through our solar system very frequently. However, the increasing accuracy of telescopes such as ATLAS, coupled with emerging technologies like Artificial Intelligence, has enabled early detection of these interstellar objects like never before in human history. Consequently, the detection of Oumuamua, Borisov, and now, 3I/ATLAS, marks a turning point in the study of ISOs.

In addition to their scientific importance, the increasing frequency and detection of ISOs have alarming implications when it comes to planetary defence. While 3I/ATLAS does not pose a collision threat, the inherent unpredictability of ISOs due to their massive velocities and unusual trajectories raises disturbing possibilities for the future of the planet. As such, physical interception of ISOs is important not just from an astronomy and space exploration science perspective, but also from the point of view of global defence. NASA is already playing a pioneering role in the realm of planetary defence through initiatives such as the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission and the subsequent Hera Mission being conducted in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA). The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has also expressed its interest in participating in planetary defence initiatives.

When it comes to ISOs specifically, though physical interception is not impossible, it is a difficult, costly, and time-consuming endeavour. A mission concept called “Bridge” has been proposed by NASA, which would, in principle, intercept ISOs once they are identified, though this would require a 30-day launch window. On the other hand, the ESA is pursuing a different approach known as the “Comet Interceptor Mission,” wherein it will launch a spacecraft in 2029 into a parking orbit at the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2), thereafter lying in wait for ISOs to intercept. Simultaneously, there are other ongoing missions meant to shed further light on dark comets. For instance, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Hayabusa2 Mission is scheduled to land on a dark comet known as 1998 KY26 (previously identified as an asteroid) in 2031.

Conclusion

With speculation still rife with regard to the exact nature of 3I/ATLAS, enhanced observational abilities, as well as the aforementioned initiatives, are bound to enhance our limited understanding of ISOs in the future. In addition to shedding light on their unique properties, these efforts may also enable us to uncover some of the deeper mysteries surrounding cosmology, such as the origins of the known universe, the nature and properties of dark matter, and the evidence of life outside our solar system. Moreover, the increasing instances of ISO detection have also served to bring the criticality of planetary defence into the limelight, an issue which has not necessarily received the requisite attention in the past. In this regard, the role of enhanced ISO detection and interception capabilities in the future cannot be downplayed or ignored, necessitating their immediate integration into national and global space policy, along with greater global cooperation in the field.

- About the author: Prateek Tripathi is a Junior Fellow with the Centre for Security, Strategy and Technology at the Observer Research Foundation.

- Source: This article was published by the Observer Research Foundation.

Observer Research Foundation

ORF was established on 5 September 1990 as a private, not for profit, ’think tank’ to influence public policy formulation. The Foundation brought together, for the first time, leading Indian economists and policymakers to present An Agenda for Economic Reforms in India. The idea was to help develop a consensus in favour of economic reforms.

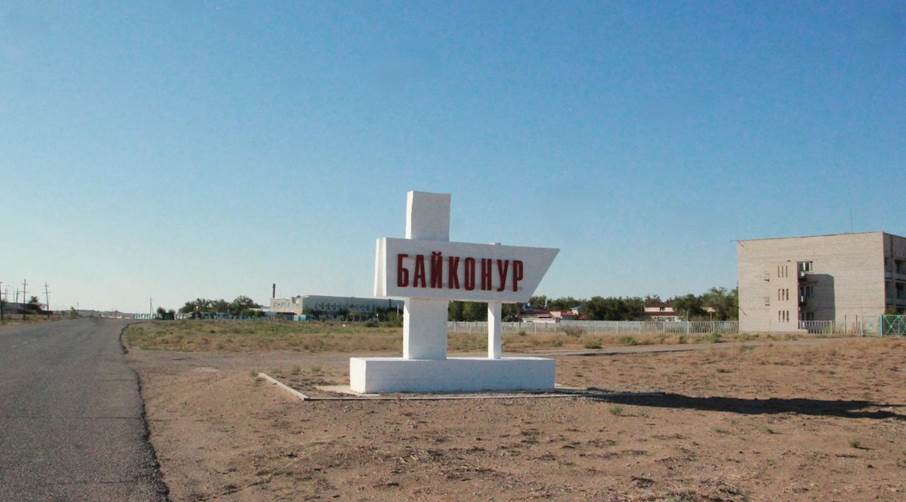

Baikonur Cosmodrome, an icon of Russian space exploration neglected in recent times by Moscow, is seeking a future.

The legendary Soviet spaceport, situated on the Kazakh Steppe in southern Kazakhstan, is celebrating its 70th anniversary this year. Run as a Russian exclave by Moscow since the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, Baikonur nowadays has the added difficulty that it is subject to international sanctions against Russia.

Baikonur sign on the territory of the cosmodrome (Credit: Emma Collet).

“The first man in space… That was something!” exclaims Azamat Doszhanov, director of KazCosmos, Kazakhstan’s national space agency, as he drives past yet another poster glorifying Yuri Gagarin. The smiling face of the most famous Soviet cosmonaut is omnipresent at Baikonur Cosmodrome, always accompanied by the inscription “Poekhali!” (“Let’s go!” in Russian), Gagarin’s famous phrase, uttered before he embarked on his first journey beyond Earth’s atmosphere on April 12, 1961.

As a symbol of the golden age of space exploration, Baikonur proudly showcases the USSR’s pioneering legacy – from the very first spacecraft launched in 1957, to the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, in 1963, and, of course, the sensational journey of Gagarin.

As you drive along the main road cutting across the largest cosmodrome in the world – it covers more than 6,700 square kilometres (2,587 miles) – clusters of infrastructure appear on the horizon, breaking the endless line of the steppe. The Soviets chose the location in 1955, noting it was utterly deserted except for some horses and camels that roam the red sands, and is close to the Equator, offering one of the shortest trajectories to space.

Memories of Soviet space conquest

The facilities, including the launch pads, slowly emerge from the vastness. Each piece of Baikonur is separated by dozens, even hundreds of kilometres, “to prevent the total destruction of the cosmodrome in case of an American bombing at the time,” explains Azamat Saigakov, space engineer and deputy director at Russian-Kazakh joint venture Bayterek.

Indeed, the spaceport was built at the dawn of the Cold War, initially serving as a testing base for the first Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile, the R-7. Baikonur’s location was kept so secret that the Americans only discovered it two years after construction began.

The site weathered the chaos of the Soviet Union’s collapse in the 1990s “relatively smoothly,” recalls Sergei Sopov, founder and first director of Kazakhstan’s National Space Research Agency (1991–1993), who spent most of his career at Baikonur. “After 1991, the cosmodrome remained under military control, reporting to the nuclear and space forces of the Commonwealth of Independent States [CIS]. They were therefore officially separate from the new national entities being formed on the territory of the former Soviet Union.”

Sopov took part in drafting the 1994 agreement between Russia and Kazakhstan, under which Moscow leased the cosmodrome and the closed city of Baikonur — home to 110,000 people at the time — for 20 years, paying Astana $115mn annually. In the 2000s, the cosmodrome was gradually demilitarised and repurposed for commercial missions and crewed flights to the International Space Station (ISS).

The lease has since been extended to 2050, leaving the site under Russian ownership, with Roscosmos and its subsidiaries still operating there. For Russians, Baikonur remains a living monument to the space race, with 43% of Russians still seeing Soviet cosmic achievements as a source of pride, according to the Levada Center.

Yet given the challenge of the Russian Vostochny Cosmodrome, inaugurated in the Russian Far East in 2015, Baikonur’s glory days are now a thing of the past. At the foot of the “Gagarin” launch pad, abandoned equipment speaks of this decline. Since 2019, the pad has been inactive. It was recently converted into a tourist attraction. Several other launch ramps have also been out of service for years, rusting under the scorching Kazakh sun. Of the 10 existing launch complexes, only three remain operational for the “Proton-M” and “Soyuz” programmes.

The Gagarin launch pad, from which Yuri Gagarin took off for space, is nowadays a tourist attraction (Credit: Emma Collet).

Russia, a declining commercial space power

“It’s like choosing between an old Soviet Moskvitch car and a new foreign brand,” Doszhanov says of the inactive sites. “The first still runs fine, but you can’t bet on old cars for ever.” In other words, the infrastructure is ageing, and Russia has invested little in modernisation.

After the USSR’s collapse, Russian space investments plummeted amid an economic crisis. Despite a $50bn plan announced by Vladimir Putin in 2013 for Russian space programmes over seven years, the country — once neck-and-neck with the United States in the space race — has fallen far behind.

“Russia is a second-tier space power today,” says Bruce McClintock, head of space research at RAND and former US defence attaché in Moscow. He highlights the impact of corruption within Russian space programmes and the international sanctions imposed since 2022, which have severely hit Russia’s space industry.

“Russian launch vehicles depend heavily on Western electronics, particularly from the US and Europe. Since the war in Ukraine, Russia has lost access to most of these components, grounding many of its satellites,” notes Bart Hendrickx, a veteran analyst of Russian space programmes and professor at Ghent University in Belgium.

Cooperation programmes with Western partners — apart from crewed ISS missions — have also ended. This includes the “Soyuz” launches from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana with the European company Arianespace. Isolated, Russia launched only 1% of the world’s satellites in 2022.

The Kremlin continues to nurture ambitious projects, such as building its own space station by 2030 from launches at the Vostochny Cosmodrome. Moscow is also touting new orbital weapon systems, including the potential deployment of nuclear-capable satellites. These operations are reserved for its military Plesetsk Cosmodrome, located in Arkhangelsk region in northern Russia, and illustrate how civilian space budgets are increasingly redirected toward military work.

Hopes for a revival with “Soyuz-5”

Baikonur, meanwhile, is rarely mentioned in Russia’s grand space plans. In Moscow’s eyes, its only real value now lies in crewed ISS missions launched from its Soyuz pad — the last symbol of cooperation between Russia and the rest of the world.

But the Bayterek joint venture, created in 2004, shows no sign of wrapping up. On site No. 45, home to the imposing “Zenit” launch complex, preparations are under way to host Russia’s new “Soyuz-5” rocket, built in Samara. After years of delays, its first test flight is now scheduled for December.

Under the blazing sun, teams work on the launch pad. Amid gusts of wind and swirling dust devils, technicians adjust the rocket’s “fifth leg,” a cable mast that powers the vehicle before liftoff.

Launch pad at the Zenit launch complex, from which the Russian Soyuz-5 rocket will take off. (Credit: Emma Collet).

Modernisation is needed because the pad once launched a different rocket: the “Zenit,” assembled in Ukraine’s Dnipro with Russian components. This cooperation collapsed after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the start of the war in Donbas.

“In terms of modernisation, the main difference is the size of the Soyuz-5 compared to the Zenit,” explains Syrym Intymakov, director of Baiterek’s Baikonur branch. “But the technology is basically the same — we’ve reused as much of the Zenit’s configuration as possible.”

The rocket can carry 17 tonnes to low Earth orbit, but what will its commercial future be? Excluded from European and Western markets due to sanctions, “its customer base will mostly be allied countries in the Middle East and Africa, which don’t have their own space programmes and only need one or two satellites,” assesses Florian Vidal, a researcher at the University of Tromso in Norway and associate fellow at IFRI. “These are small-scale missions that can’t achieve the decades-long profitability Russia once had with European partners.”

Kazakhstan’s space ambitions for Baikonur

The Zenit pad’s €1.5bn modernisation is funded not by Russia, but by Kazakhstan. Since 2018, the Central Asian country has owned the cosmodrome’s eastern facilities, removed from the Russian lease.

This year, the Gagarin launch pad and Buran assembly building — home to decaying prototypes from the 1970s — have also returned to Kazakh jurisdiction.

While these two sites are set to become tourist attractions, other strategic but unused facilities could also pass into Kazakh hands, at a time when Russia’s presence at Baikonur seems increasingly uncertain.

A rusting prototype of the planned Soviet "space shuttle", named "Buran". The programme to build it was formally abandoned in 1993 (Credit: Panikovskij, cc-by-sa 4,0).

“Russia might remain for a limited time in Baikonur, at least to keep a foothold in Central Asia,” says Nourlan Asselkan, editor-in-chief of the Kazakh journal Space Research and Technology. “Moreover, moving all its programmes to Vostochny would currently exceed its capacity.” The real decision point will come after 2028, when Roscosmos and Nasa end ISS operations.

In the meantime, Kazakhstan is trying to attract foreign investors and lay the groundwork for becoming an independent space power, eyeing the creation of its own ultra-light launcher. This year, Prime Minister Olzhas Bektenov announced plans for a special economic zone at Baikonur dedicated to “national space projects and foreign startups,” covering some 1,750 square kilometres — about a quarter of the cosmodrome.

Entrance into sector of "Bayterek", the Kazakh-Russian joint venture established in 2004 (Credit: Emma Collet).

Talks are already under way with Indian and European companies, but China appears best positioned among the “newcomers” for Kazakhstan’s space sector. During Xi Jinping’s visit to Astana last year, Beijing pledged 100mn yuan (€13mn) for joint space projects. Chinese startups, already active in commercial satellite launches, could become the first foreign operators to use Baikonur’s facilities.

“That would be fully consistent with China’s Belt and Road vision,” says Vidal. “Beijing is a regional power and a close neighbour of Kazakhstan — Baikonur could naturally meet its growing launch needs.” A new space race is taking shape in the Kazakh steppes.

SwRI-built instruments to monitor, provide advanced warning of space weather events

SwRI instruments integrated into space weather observatory expected to launch in Sept. 2025

image:

The SwRI-developed Solar Wind Plasma Sensor (SWiPS) is integrated into NOAA’s Space Weather Follow On-Lagrange 1 (SWFO-L1) observatory satellite to provide real-time, 24/7 observations of the solar wind and its plasma. It will measure the properties of its ions, including those associated with space weather events that can affect Earth’s magnetic field. SwRI will also support satellite operations and data analysis.

view moreCredit: Southwest Research Institute

SAN ANTONIO — September 17, 2025 — Two instruments developed by Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) are integrated into a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite set to launch into space as a rideshare on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket no earlier than Sept. 23, 2025.

The SwRI-built Solar Wind Plasma Sensor (SWiPS) and Space Weather Follow-On Magnetometer (SWFO-MAG) are two of four instruments integrated into NOAA’s Space Weather Follow-On Lagrange 1 (SWFO-L1) satellite. SWFO-L1 will monitor and study the Sun’s corona and measure the solar wind, high-energy particles and the interplanetary magnetic field. SwRI will support operations and data analysis for its onboard instruments. SWFO-L1 will share a ride to space with NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission before separating and orbiting the Sun at Lagrange point L1, a point nearly one million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

As part of SWFO-L1’s suite of space weather-observing instruments, SWiPS and SWFO-MAG will capture 24/7 observational data in real-time to monitor abrupt changes in the solar wind often associated with coronal mass ejections and other space weather phenomena. When these phenomena interact with Earth’s magnetic field, they can have adverse effects on Earth and near-Earth technology. These effects can include electrical power grid disruptions, Global Positioning System navigation errors, spacecraft damage or potential harmful radiation exposure to astronauts. The SWFO-L1 data will support NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and help predict and prepare for potential space weather impacts.

“I am thankful to all the team members who spent countless hours designing, building, and testing SWiPS and integrating it into the satellite,” said SWiPS Principal Investigator Dr. Robert Ebert, assistant director of SwRI’s Department of Space Research. “The data that SWiPS and the other instruments collect will help keep U.S. space assets safe.”

SWiPS monitors solar wind plasma to measure the properties of solar wind ions, particularly those associated with space weather events. SWFO-MAG will monitor the Sun’s magnetic field for abrupt changes that are often precursors for geomagnetic storms that, when they interact with the interplanetary magnetic field, can affect life on Earth. The Space Research Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences provided SWFO-MAG’s front-end electronics and its core electronics microchip.

“SWFO-MAG is designed to provide NOAA and the scientific community at large with important data about the solar wind as it approaches Earth. The magnetic field variations are a key parameter in predicting the severity of a solar storm’s impacts on Earth’s environment,” said SWFO-MAG Principal Investigator Dr. Roy Torbert from SwRI, who is based at the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. “SWFO-MAG, which was built and tested in conjunction with UNH, will produce data to help mitigate space weather impacts.”

The SWFO-L1 mission is a partnership between NOAA and NASA. The NASA Goddard Space Flight Center managed the development of the SWFO-L1 observatory on NOAA’s behalf and to NOAA’s specifications. NOAA will operate SWFO-L1 from its Satellite Operations Facility in Suitland, Maryland., and process the space weather data at its Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colorado.

The joint launch with NASA’s IMAP mission and the Carruthers Geocorona Observatory is expected no earlier than Tuesday, Sept. 23, 2025. SwRI also plays a key role in the IMAP mission, managing the payload and developing onboard scientific instruments designed to analyze and map particles streaming from interstellar space and to help scientists understand particle acceleration near Earth.

NASA and NOAA oversee the development, launch, testing and operation of all the satellites in the Lagrange-1 Series Project. NOAA is the program owner and provides the requirements, funding, operations management, data products and information dissemination to users. NASA and its collaborators develop and build the instruments and spacecraft and provide launch services on behalf of NOAA.

For more information, visit https://www.swri.org/markets/earth-space/space-research-technology/space-science/heliophysics.

The SwRI-developed SWFO-MAG will monitor the Sun’s magnetic field for abrupt changes that can serve as precursors for geomagnetic storms that can interact with the interplanetary magnetic field and affect life on Earth. NOAA’s SWFO-L1 satellite will launch from KSC as a rideshare with IMAP no earlier than Sept. 23, 2025.

Credit

Southwest Research Institute

No comments:

Post a Comment