Falklands Oil Megaproject Breaks Free After 15 Years

- After 15 years in limbo, the Sea Lion oil project reached FID on December 10, unlocking 315 Mbbls of recoverable oil and a 50,000 b/d deepwater development targeting first oil in 2028.

- Israel’s Navitas Petroleum took control with a 65% stake, committing ~$2.1 billion in phased development capex.

- The project moves ahead despite Argentinian opposition and a disputed legal backdrop, positioning Sea Lion as the largest South Atlantic deepwater oil project outside Brazil.

After 15 years of delay, redesign, and skepticism, the Sea Lion oil project has finally crossed the line from ambition to execution. On December 10, partners Navitas Petroleum (Israel) and Rockhopper Exploration (UK) took a long-awaited final investment decision (FID) on what will become the largest deepwater oil development in the South Atlantic outside Brazil. Few projects of comparable scale have taken so long to move from discovery to sanction, and fewer still have done so under such persistent political, legal and financial headwinds. With FID now secured, Sea Lion formally enters the development phase, planned to last 35 years or longer, with first oil targeted for 2028.

Discovered in 2010 by Rockhopper Exploration, Sea Lion was the Falkland Islands’ first commercial oil find, but its remote location and legal difficulties made it vulnerable to shifts in capital investment. Premier Oil’s $1 billion entry in 2012 was meant to accelerate development, yet the post-2014 oil price slump and the retreat of listed companies from capital-intensive frontier projects left Sea Lion effectively frozen until the end of the decade. That changed with the arrival of Israel’s Navitas Petroleum in 2020. Initially a minority investor, Navitas became the project’s operator and majority owner in 2021 after Harbour Energy exited, restructuring both ownership and financing. The shift replaced public-market caution with private capital willing to absorb long-cycle risk — a change that ultimately unlocked the project and led to the FID.

Related: Top Exporters Boosted Natural Gas Supply in October

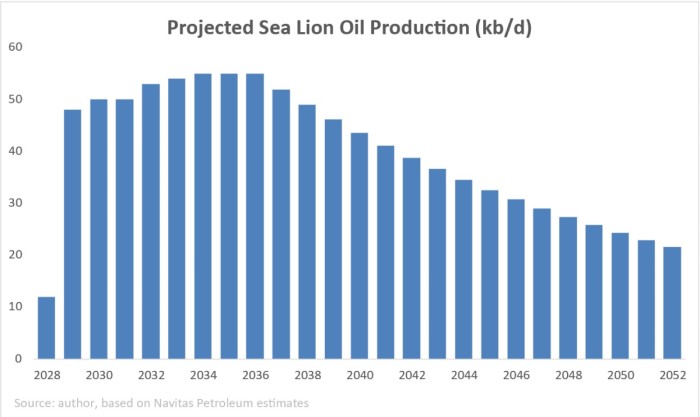

Sea Lion contains approximately 315 million barrels of recoverable crude oil, producing a sweet, low-sulphur grade with 28–29° degrees API and just 0.2% sulphur. Development has been designed in phases to manage capital intensity and reservoir performance. The sanctioned Phase 1 targets 170 million barrels of oil, with peak production of 50,000 b/d and 11 wells planned, while first oil is expected in 2028. Phase 2 is planned to recover a further 144 million barrels, with 12 additional wells to be drilled roughly three years after first oil to extend the production plateau. The entire field will be developed around a single redeployed Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) vessel.

Navitas’ role has been central to unlocking the project. By the time it entered, the project had become too capital-intensive and politically exposed for publicly listed companies constrained by balance-sheet discipline and shareholder scrutiny. Navitas Petroleum, by contrast, has built its strategy around long-cycle offshore developments, particularly FPSO-based projects, where bespoke financing, patience and tolerance for high geopolitical risk are essential. That approach was proven in Israel’s Leviathan gas field, where Navitas held a 7.5% stake through construction, saw first gas in 2019, and exited in 2021 via a sale to Mubadala Petroleum once the project had been de-risked. A similar pattern played out at the Shenandoah deepwater project in the Gulf of Mexico. There, Navitas acquired 49% and operatorship of a stalled development, restructured legacy debt and helped secure a $1 billion financing package in 2021 backed by Israeli banks and institutional investors. Shenandoah came onstream in early 2025 and is now generating cash flow, reinforcing Navitas’ ability to revive projects others could not advance.

Sea Lion now follows Navitas’ established strategy. After the Israeli company joined the project, a funding agreement was put in place under which it covered 100% of Rockhopper’s project costs prior to sanction, effectively reviving an asset that had been financially frozen for years. Phase 1 is expected to cost around $1.8 billion to first oil and roughly $2.1 billion through completion once contingencies and financing costs are included. In contrast to Leviathan, however, Sea Lion represents a deeper commitment: with a 65% stake and operatorship, Navitas appears positioned not only to carry the project through de-risking, but to remain at the centre of the development well into its producing life.

The project has been facing a series of impediments, and only time will show if the owners will be able to navigate through them. Firstly, the legal framework underpinning Sea Lion project’s exploration and production is one of its most notable peculiarities. Following the UK’s de facto military victory in the 1982 Falklands War over Argentina as well as the 2013 referendum in which 99.8% of the Falkland Islands’ population voted to remain a British Overseas Territory, the islands are administered de facto and de jure under UK law, with sovereignty recognised in practice by most countries.

At the same time, the United Nations does not recognise sovereignty claims by either the UK or Argentina, lists the Falklands as a non-self-governing territory and continues to call on the two nations to negotiate. That unresolved status creates enduring political risk but has not prevented the Falkland Islands Government from issuing licences, regulating petroleum activity, and levying fiscal terms. Under the local framework, Sea Lion is subject to a royalty rate of 9% and corporate income tax of 26%, in line with the Falklands Islands Upstream Summary. Ironically, the UK is strangling its domestic oil and gas industry with a 78% profit tax rate, but entertains such a lenient tax regime in its overseas territories.

This way, politically, the project remains contentious. Buenos Aires has consistently opposed Sea Lion from the earliest exploration phase through to the FID announcement, describing the licences under which drilling and development are conducted as ‘unlawful’, branding the project ‘unilateral and illegitimate’, and citing the UN resolutions related to the sovereignty dispute. Argentina’s reaction to FID followed this well-established pattern. However, Buenos Aires has limited ability to intervene in the project from either a military or legal standpoint. Vessels en route to the Falklands do not need to pass through Argentine territorial waters, meaning Argentina's only recourse is to withhold logistical support, hoping that the difficulties of transporting necessary equipment and workforce from the UK to the Falklands via air or sea would make the project as financially unpleasant as it can be. The second major hurdle lay in a series of engineering and permitting bottlenecks that only began to clear this year. Located more than 220 kilometres offshore and entirely without supporting infrastructure, Sea Lion can only be developed via an FPSO – a solution that is both capital-intensive and constrained by limited vessel availability. However, early 2025 saw a long-anticipated breakthrough, when a front-end engineering design contract was awarded for a redeployed FPSO, marking a clear shift from conceptual work to execution planning. Environmental permitting, long a chronic obstacle, also moved forward. An Environmental Impact Assessment submitted in 2024 progressed through review, and in November 2025, the Falkland Islands’ Department of Mineral Resources concluded that the Environmental Impact Statement submitted by Navitas in July 2025 – the third version since the first proposal – satisfied local legislation and required only minor amendments. With engineering, permitting, and financing aligned, the case for an FID finally became robust.

With regulatory sanction secured and an FID in place, attention is already turning to what Sea Lion could unlock next. The most obvious candidate is the Darwin deepwater gas-condensate discovery offshore the Falkland Islands, drilled by Borders & Southern Petroleum in 2021 in around 2,000 metres of water and estimated to contain 460 million barrels of recoverable liquids. Darwin has so far remained stranded by depth, cost and lack of infrastructure, but Sea Lion’s success could alter the economics of further developments in the basin.

Argentina, meanwhile, has been testing its own offshore potential. Buenos Aires granted exploration permits to YPF, Equinor and TGS, and Equinor drilled the ultra-deepwater Argerich-1 pilot well, which was ultimately declared dry. For now, most upstream investment in Argentina continues to flow from the Vaca Muerta shale rather than frontier offshore plays.

Sea Lion does not resolve the sovereignty dispute over the Falkland Islands, nor does it eliminate political risk in the South Atlantic. What it does demonstrate is that with the right capital structure, operator profile and timing, even projects long dismissed as commercially unviable can be brought to sanction. If the development performs as planned, Sea Lion may not only anchor Falklands offshore production for decades but also reshape investor perceptions of one of the industry’s last major frontier basins.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment