Study Challenges the Assumptions About “Thinning” Forests

Previously logged and Thinned stand that burned in Jocko Lakes Fire Montana.

Federal wildfire policy that advocates “fuel reduction” under the assumption that logging projects will curb large blazes and save homes is challenged by a recent paper that questions whether this is the most effective or best way to protect communities from wildfire.

This Montana site was thinned(logged), even clearcut in places, prior to the high-severity blaze which occurred under “red flag” weather conditions. Photo by George Wuerthner

A new publication: Ecological trade-offs of mechanical thinning in temperate forests by Lindenmayer et al. challenges the underlying assumptions, trade-offs, and impacts associated with mechanical thinning (read logging).

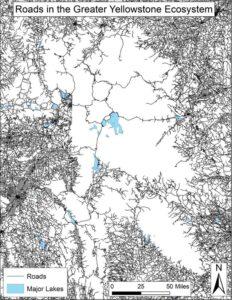

The above graphic shows the road network that already occupies the public and private lands in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. New roads to implement to wildfire thinning projects will only increase the numerous negative ecological impacts resulting from roads.

As with many resource exploitation proposals, there are numerous unaccounted harms, particularly ecological costs, that are seldom considered, which proponents of thinning conveniently ignore.

In recent years, thinning has become the dominant means of altering “fuel loading” (think of it as destroying wildlife habitat) based on the assumption that it can mitigate fire risk.

While a diversity of treatments falls under the umbrella of “thinning,” from hand removal of understory saplings and small trees to major logging operations that eliminate large, old, mature trees, generalizations about effects are variable. However, the majority of thinning projects I have seen throughout the West are more of the latter than the former.

The other major variables are weather and terrain. Under low to moderate fire weather conditions, thinning may reduce fire spread, which is not surprising, as most fires, even without fire suppression, will remain small and self-extinguish.

It is critical to understand from a public policy perspective that fires that ignite under so-called “red flag” conditions readily skip over, burn through, and around thinned stands.

Indeed, thinning can create conditions that favor fire spread by reducing shade and moisture. A reduction in canopy cover exposes the forest floor and surface fuels to drying and moisture deficiency. Thinning also allows greater wind penetration.

The only wildfires that are important from an ecological and economic perspective are the large, typically high-severity blazes. These blazes make up less than 1–2% of all wildfires but are responsible for 95–99% of all acreage charred.

In many large thinning operations, extensive road networks are required to remove trees. Roads have numerous impacts on wildlife, soil erosion, water quality, and habitat fragmentation, all of which are too frequently ignored. Plus, wildfires are four times more likely to occur near roads. Therefore, more roads increase the probability of human ignitions.

This naturally leads to the question of whether any thinning is worth the costs.

The goal of most federal and state funding is to reduce or eliminate such large blazes (pejoratively called catastrophic). Still, the reality is that thinning is seldom effective at modifying wildfire burning under “red flag” weather conditions.

This raises the point made by the authors of this study. If thinning isn’t achieving the goal of reducing large wildfires (which, from an ecological perspective, may not be desirable in the first place), is it reducing funds for fire prevention and community defense?

Despite abundant evidence that home hardening is the best way to safeguard communities, funding priorities do not reflect this.

For instance, in California, 98% of wildfire prevention funding is used to log backcountry areas in the name of “fuel reductions”. Only 1% is spent on home hardening and community protection. A total of $38 million of the state’s budget is earmarked for home hardening out of a total budget for ‘wildfire and forest resilience” of $3.6 billion.

Furthermore, the true ecological costs of thinning are frequently ignored. These include the spread of weeds, soil compaction leading to higher runoff rates and, hence, more erosion, loss of wildlife habitat and fragmentation, and loss of carbon. All of these have economic consequences as well.

Another issue emphasized by the authors is that natural self-thinning often results in lower tree density over time, without the multiple negatives associated with mechanical thinning.

Indeed, much mechanical thinning is often justified by suggesting it increases “resilience” by limiting or eliminating natural evolutionary thinning agents, such as insects, disease, drought, and wildfire, all of which are more effective at selecting which trees survive or die.

No forester with a paint-can mark for removal knows which individuals have a genetic capacity to resist or survive under different evolutionary conditions. As ecologist Aldo Leopold stressed, maintaining all the “parts” is the first line of intelligent tinkering.

Mechanical thinning also degrades forest ecosystem resilience by reducing physical features critical to ecosystem health, such as snags and down wood, and by disrupting evolutionary processes.

Furthermore, thinning can increase carbon emissions by up to five times those from fire. Thinning can create a multi-decadal carbon deficit, with residual tree growth failing to compensate for the removed biomass.

A problematic aspect of “fuel treatments” is that they have a short effective window of 5–20 years, if they are effective at all. And the probability that a wildfire will encounter treated (read logged) areas during this time period is minuscule. The probability that a fire will encounter a thinned stand during the period when it might influence wildfire severity and spread is about 1% of treated forests. This means most thinning projects, and the subsequent ecological and economic costs are unnecessary and unwarranted.

The authors of this paper make a compelling argument that the presumed benefits and effectiveness of thinning projects have questionable paybacks, and numerous unaccounted costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment