Americans who’ve lost loved ones to Covid-19 say they feel like ‘everyone wants you to get over it’

Iffah Kitchlew

Sun 13 Mar 2022

We have lost a great deal within the last two years. The worldwide Covid death toll has surpassed 6 million lives. In the US, nearly a million people have succumbed to the virus – more than the number of people who died during the civil war. In fact, more lives were lost to Covid in the US last week alone than in the attacks on Pearl Harbor and 9/11 combined.

The Covid cloud is starting to lift – but two years on, its legacy of grief lingers

And now, at the pandemic’s second anniversary in the US, we are watching a terrifying war unfold abroad. The immense cumulative toll on the public’s psyche has felt impossible for many to escape.

“It’s like losing someone in a car accident and being surrounded by car accidents, 24/7,” said Sabila Khan, a 42-year-old from Jersey City, New Jersey, whose father died of Covid-19 in April 2020.

The world is trying to move on: mask mandates are relaxing and quarantine periods are shortening. But this rush to reinstate a sense of normalcy may have inadvertently robbed us of the time we need to process many layers of trauma. It’s important to ask ourselves: have we been given the space to grieve the scale of what we have lost?

“That exposure to so much death on a massive scale is so unsettling to a person’s mental health. It made people realize just how precarious their lives are,” said Holly Prigerson, director of the Cornell Center for Research on End-of-Life Care. “It’s a recipe for a perfect psychological storm.”

If anything lies in the eye of this “psychological storm”, it is grief. This might explain the response to the most recent surge in the pandemic. The flu-ization of the Omicron variant – meaning the push to treat the virus as an endemic illness similar to the flu – has changed the narrative on Covid. Workers are returning to their offices, restaurants are no longer requiring vaccinations, festivals as big as Coachella are heading to get rid of vaccine and Covid testing requirements.

The apparent lack of severity of Omicron’s symptoms and the advent of the Covid vaccine has given people a “false sense of security”, according to Amna Zaki, a psychiatric nurse at St Francis medical center in Trenton, New Jersey. “By fall of last year people’s attitude was ‘We’re done, it’s over,’” she said.

But for those who have seen the worst that it can do, the pandemic is far from over.

“We’re still trying to heal our grief and our heartbreak,” said Jeneffer Haynes, 38, who lost her younger brother to Covid last year. Haynes remembers sitting on a plastic chair, by herself, in a cold, palely lit hallway at Holy Cross hospital’s Covid ward in Germantown, Maryland, watching as he struggled to breathe. After eight days in a small grey hospital room, Haynes’ brother died. He was 30 at the time.

Haynes says she still has not wrapped her head around the events of her brother’s death. And as the world reverts to business as usual, she says people who have experienced a Covid loss like her feel as if their grief is being ignored.

“I feel like an outcast,” said Manisha Patel, a 43-year-old from Pennsylvania whose 76-year-old father died of Covid at the beginning of the pandemic.

Coping with this kind of grief can be particularly challenging because of the circumstances of a Covid-related loss, said Debra Kaysen, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University’s School of Medicine.

“This is a place where normal mourning is interrupted. Where it is hard to finish or to move forward with the grieving process,” she added.

The interruption of mourning traditions can worsen mental health issues for the bereaved. A study on the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone found that the disruption to community mourning practices increased the severity of distress among those who had lost someone to Ebola, making it more difficult for them to cope with their grief.

The feeling that everybody else is moving on from the pandemic, then, can complicate this grief.

“As the world is shifting, people may feel like they are being left behind. For them, it’s not back to normal. And it really can’t be,” said Kaysen.

But not everyone has lost loved ones over the last two years. About 9 million people are grieving a Covid loss, an average of nine close relatives have been left bereaved for every Covid death in the US. This also means that there are 291 million people who are not grieving.

“It is harder to have a sense of shared grief, because we are not all sharing it evenly,” said Kaysen. The uneven distribution of Covid losses has created some “tension” between those who want to get back to their lives and those who do not have that luxury, she added.

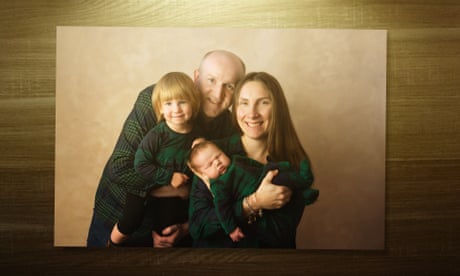

That disconnect has, in a way, stolen the time and space needed by those who have lost someone during the pandemic to grieve properly. Patel lost her father two years ago; her teenage daughter, the “favourite grandchild”, still has not cried.

For Khan, whose father was already suffering from Parkinson’s disease when he was diagnosed with Covid, his death feels like an “inconvenient statistic” that ruins people’s “rosy-colored picture” of the pandemic’s regression. “Everyone wants you to get over it,” she said.

We cannot assume that people will “just move on and be over it, because that’s not going to happen”, said Prigerson.

In this situation, memorializing those lost to Covid, in a way that the Aids Quilt has done for Aids-related losses, might be a much-needed way to heal from these deaths, said Kaysen. We could create a sense of “shared mourning”, she added.

This is especially important because people are still losing their loved ones to the virus. According to the WHO, half a million people worldwide have died of Covid between the time Omicron was first declared a variant and the beginning of February. About a third of all Covid-caused children’s deaths in the US have happened during the Omicron surge.

“If people could just hear us, from the people who have lost a loved one, to see the severity of this,” said Patel.

However, there might be a silver lining for what people can do for each other in this trying time.

In search of a space that would understand her grief, Khan created a Facebook group based in the US for those who have lost someone to Covid. The group is working to provide access to affordable mental health services for its members as well. Haynes has dedicated much of her time to equitable vaccine distribution in Maryland, where she lives, among disadvantaged and minority communities.

We have lost a great deal to two years of a pandemic, but we have not lost everything. There is hope for our communities to come together, to become more empathetic, according to Kaysen.

“Folks have learned ways to be more interconnected, even when we are not seeing each other in person. And that has the potential to help us build a sense of community even during times when we can’t be together.”