Cool to be kind: being nice is good for us – so why don’t we all do it?

As science proves that acts of kindness benefit both giver and receiver, we ask why some people are so much better at putting others first

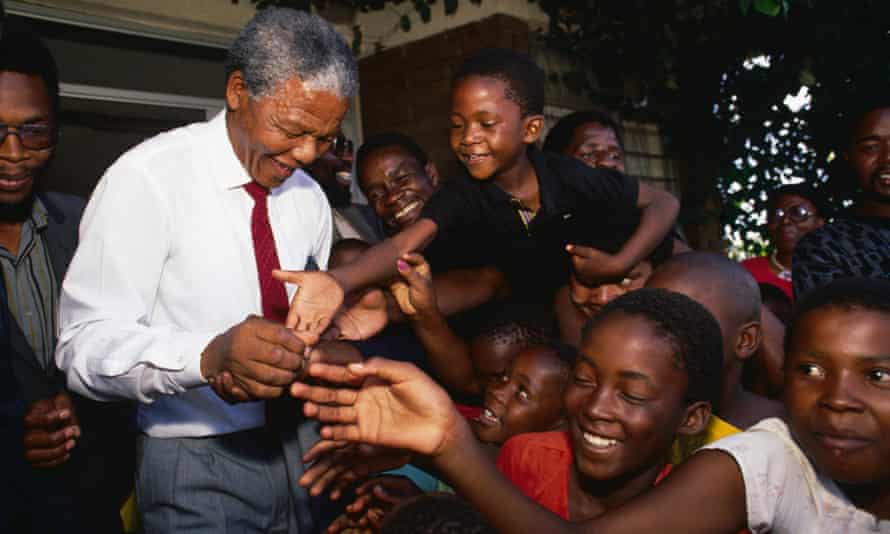

Guinea-Bissau's Braima Suncar Dabo helps Aruba's Jonathan Busby to the finish line during the men's 5,000m heats at the 2019 IAAF World Athletics Championships in Doha.

Photograph: Kirill Kudryavtsev/AFP/Getty Images

Donna Ferguson

Sun 13 Mar 2022 10.00 GMT

It was freezing cold the day Neil Laybourn saw a man in a T-shirt sitting on a high ledge on Waterloo Bridge and made a split-second decision that would change both their lives for ever. “It’s hard to pin down what it was that made me stop… but it would have played on my mind if I hadn’t,” he said. “That’s not how you live your life is it? You don’t just walk past when you see someone in need.”

On that January morning in London’s rush hour, hundreds of other people were doing exactly that. But Laybourn didn’t and – it turned out the man, Jonny Benjamin, was contemplating suicide. Six years later he would launch a campaign to find and thank Laybourn for persuading him down off that ledge. The two of them now give talks on mental health issues and suicide prevention together.

Looking back now on that day, Laybourn says: “It’s made me much more aware of how important it is to put the amount of kindness you have in you, out into the world.”

But what is it, exactly, that makes us kind? Why are some of us kinder than others – and what stops us from being kinder?

The Kindness Test, a major new study involving more than 60,000 people from 144 different countries, has been looking into these and other questions. Launched on BBC Radio 4 and devised by the University of Sussex, it is believed to be the largest public study of kindness ever carried out in the world.

The results, which are currently the subject of a three-part Radio 4 documentary The Anatomy of Kindness, suggest that people who receive, give or even just notice more acts of kindness tend to experience higher levels of wellbeing and life satisfaction.

Other encouraging findings are that as many as two-thirds of people think the pandemic has made people kinder and nearly 60% of participants in the study claimed to have received an act of kindness in the previous 24 hours.

“It is a big part of human nature, to be kind – because it’s such a big part of how we connect with people and how we have relationships,” says Claudia Hammond, visiting professor of the public understanding of psychology at the University of Sussex and presenter of the documentary. “It’s a win-win situation, because we like receiving kindness, but we also like being kind.”

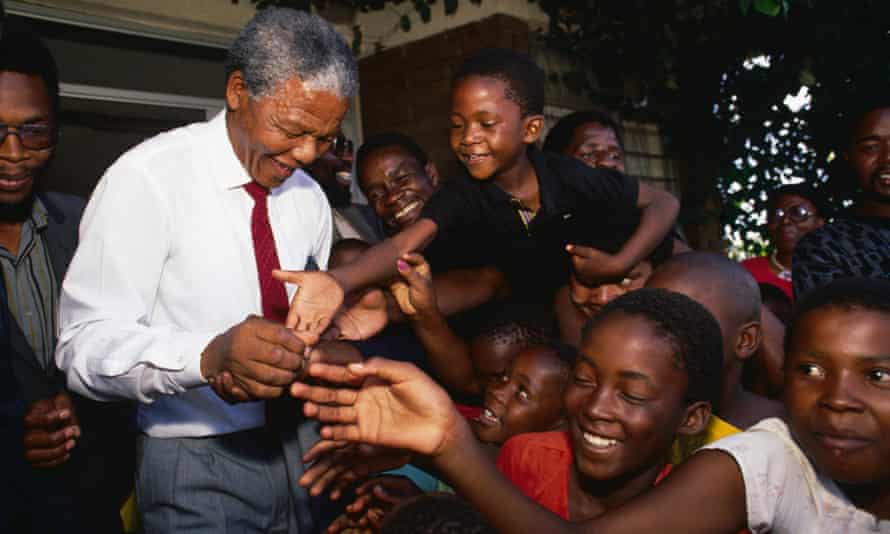

South Africans spend 67 minutes on July 18, Nelson Mandela’s birthday, on acts of kindness in their communities, to mark the 67 years he fought for social justice and equality.

Photograph: Louise Gubb/Corbis/Getty Images

Our desire to be kind is actually quite selfish, on one level, she explains. Because we have evolved to have empathy, we have all sorts of “ulterior motives” for being kind – the chief one being that it makes us feel good. “We know from brain research, there is a warm fuzzy feeling that people feel straight away. But also, it gives you the sense that you are a kind person who cares about other people. And we want to be good, we want to feel good about ourselves and what we are like.”

Your religious beliefs and your values system also help to determine how kind you are, the study shows. “We found those who believed benevolence was important were more likely to give than those who believed power and achievement were more important.”

People who have been told they should be kind are naturally more likely to notice opportunities to be kind: “They have expectations, which might be the expectations of their religious teachings or it might be the expectations of those around them,” Hammond says.

This may be one of the reasons why women who filled in the study’s online questionnaire were more likely to report being kind, receiving kindness and seeing kindness. Women may feel that they ought to report performing acts of kindness, because caring for people and comforting them is traditionally seen as a more “feminine” activity, she says.

For this reason, Hammond is concerned about the use of the hashtag #BeKind on social media. “It’s sometimes used to shut women down from talking, to suggest they can’t hold an opinion, because they’ve got to ‘be kind’. And obviously we want social media to be a kinder place. But if kindness then gets weaponised and used to stop people talking, then I think that’s a worry.”

While boys wear slogans like ‘born to win’, messages like ‘be kind’ and ‘kindness always wins’ litter young girls’ clothing . Hammond questions how much girls are stereotypically being taught, at a young age, to be caring – and whether that puts an unequal amount of pressure on girls to be kind as they grow up. “What I would hope is that boys are being taught to be nurturing too.”

Paul Dadge helps Davinia Turrell stagger from Edgware Road Tube station after the London bombings of 7 July 2005.

Photograph: Edmond Terakopian/PA

Overall, the study suggests the greatest predictor of how kind you are to others – and how kind they are to you – is not your gender, but your personality. People who scored high on extraversion, openness to new experiences and agreeableness self-reported giving and receiving more kindness, as did people who talk to strangers.

The reason for this may simply be that these people have more confidence to be kind, Hammond says. The most common barrier to kindness reported by British people in the study was a fear that their behaviour would be misinterpreted. “You need confidence to be able to offer kindness and to face the possibility that your offer of kindness may be rejected. And people may be happier to do that, and talk to strangers, if they are extroverted.”

To get over this fear of misinterpretation, Hammond recommends you remind yourself how amazing it can feel to receive an act of kindness. “When we asked people how they felt, they said warm and happy and grateful and loved and pleased.”

Luke Cameron, dubbed the “nicest man in Britain”, once spent a year doing a good deed every day to raise money for 45 different charities. It taught him that sometimes offering some help, reassurance or a kind word can make a huge difference to strangers. “It’s made me more aware of things that happen in front of me. If someone falls over in the street, there’s always going to be people who go and help and others who stand back. It’s made me one of those people who go and help. Consciously, I now just do it.”

He became that person, he says, after a “mindset shift” where he realised: “Actually, if it was me, I’d want somebody to help me. That makes you think differently about how you are with people.”

Like Laybourn and Hammond, Cameron says that you have a choice when you interact with people – and the more you try to find opportunities to be kind, the easier it gets. “It was actually the small things that I found were the most impactful,” he says.

For example, he once bought coffee for a woman who looked sad in a Costa Coffee shop and invited her to sit with him. She thanked him, saying no one had been kind to her like that in a while, and then poured her heart out to him about her friend, who was really struggling with cancer.

As she left, he realised she was wearing a wig and her eyebrows had been drawn on. “It dawned on me, she was the one going through cancer and she needed somebody to talk to about what she was going through. So she spoke to a complete stranger.” He will never forget their conversation and its impact on him. “That will always stay with me.”

Talking to strangers makes us feel more connected with each other, says Hammond: “People often think that conversations with strangers are quick and shallow and saying hello to someone in a shop doesn’t really matter. But actually it does. All of these things are received kindly by other people because they connect us. And connection is everything.”