Climate crisis: UN finds ‘no credible pathway to 1.5C in place’

Failure to cut carbon emissions means ‘rapid transformation of societies’ is only option to limit impacts, report says

A firefighter sets fire to land in an attempt to prevent wildfires from spreading in Gironde, south-west France. A rise in global temperature of 1C to date has already contributed to climate disasters. Photograph: Thibaud Moritz/AFP/Getty Images

A firefighter sets fire to land in an attempt to prevent wildfires from spreading in Gironde, south-west France. A rise in global temperature of 1C to date has already contributed to climate disasters. Photograph: Thibaud Moritz/AFP/Getty ImagesThere is “no credible pathway to 1.5C in place”, the UN’s environment agency has said, and the failure to reduce carbon emissions means the only way to limit the worst impacts of the climate crisis is a “rapid transformation of societies”.

The UN environment report analysed the gap between the CO2 cuts pledged by countries and the cuts needed to limit any rise in global temperature to 1.5C, the internationally agreed target. Progress has been “woefully inadequate” it concluded.

Current pledges for action by 2030, if delivered in full, would mean a rise in global heating of about 2.5C and catastrophic extreme weather around the world. A rise of 1C to date has caused climate disasters in locations from Pakistan to Puerto Rico.

If the long-term pledges by countries to hit net zero emissions by 2050 were delivered, global temperature would rise by 1.8C. But the glacial pace of action means meeting even this temperature limit was not credible, the UN report said.

Countries agreed at the Cop26 climate summit a year ago to increase their pledges. But with Cop27 looming, only a couple of dozen have done so and the new pledges would shave just 1% off emissions in 2030. Global emissions must fall by almost 50% by that date to keep the 1.5C target alive.

Inger Andersen, the executive director of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), said: “This report tells us in cold scientific terms what nature has been telling us all year through deadly floods, storms and raging fires: we have to stop filling our atmosphere with greenhouse gases, and stop doing it fast.

“We had our chance to make incremental changes, but that time is over. Only a root-and-branch transformation of our economies and societies can save us from accelerating climate disaster.

“It is a tall, and some would say impossible, order to reform the global economy and almost halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, but we must try,” she said. “Every fraction of a degree matters: to vulnerable communities, to ecosystems, and to every one of us.”

Andersen said action would also bring cleaner air, green jobs and access to electricity for millions.

The UN secretary general, António Guterres, said: “Emissions remain at dangerous and record highs and are still rising. We must close the emissions gap before climate catastrophe closes in on us all.”

Prof David King, a former UK chief scientific adviser, said: “The report is a dire warning to all countries – none of whom are doing anywhere near enough to manage the climate emergency.”

The report found that existing carbon-cutting policies would cause 2.8C of warming, while pledged policies cut this to 2.6C. Further pledges, dependent on funding flowing from richer to poorer countries, cut this again to 2.4C.

New reports from the International Energy Agency and the UN’s climate body reached similarly stark conclusions, with the latter finding that the national pledges barely cut projected emissions in 2030 at all, compared with 2019 levels.

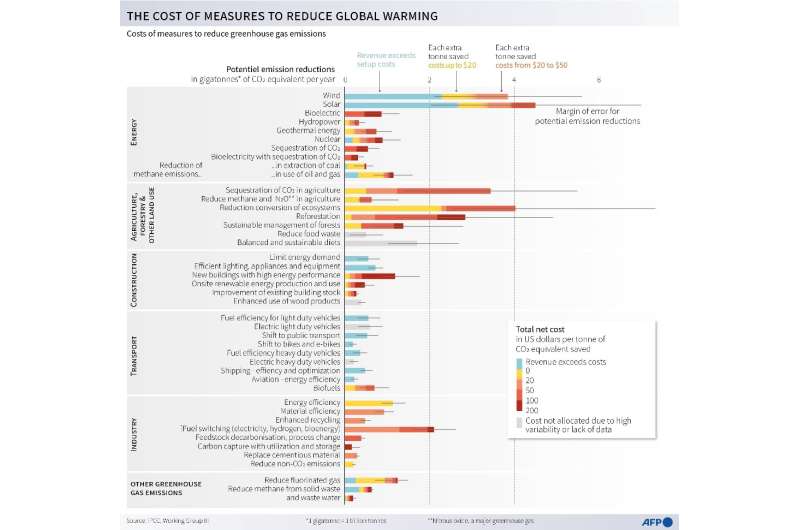

The UNEP report said the required societal transformation could be achieved through government action, including on regulation and taxes, redirecting the international financial system, and changes to consumer behaviour.

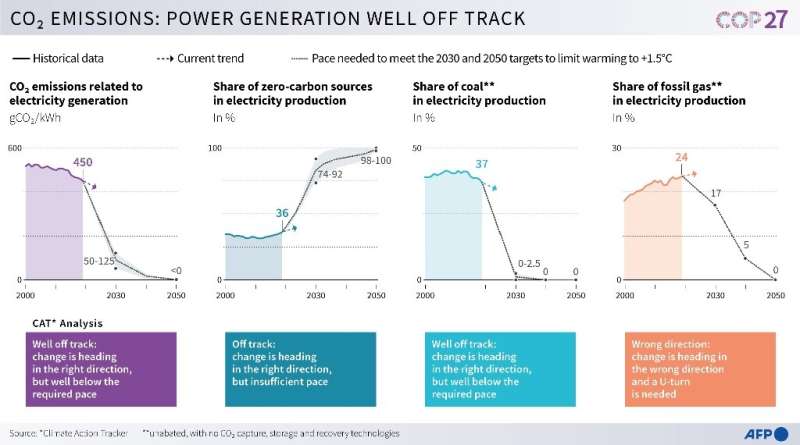

It said the transition to green electricity, transport and buildings was under way, but needed to move faster. All sectors had to avoid locking in new fossil fuel infrastructure, contrary to plans in many countries, including the UK, to develop new oil and gas fields. A study published this week found “large consensus” across all published research that new oil and gas fields are “incompatible” with the 1.5C target.

The UNEP report said about a third of climate-heating emissions came from the global food system and these were set to double by 2050. But the sector could be transformed if governments changed farm subsidies – which are overwhelmingly harmful to the environment – and food taxes, cut food waste and helped develop new low-carbon foods.

Individual citizens could adopt greener, healthier diets as well, the report said.

Andersen said: “I’m not preaching one diet over another, but we need to be mindful that if we all want steak every night for dinner, it won’t compute.”

Redirecting global financial flows to green investments was vital, the report said. Most financial groups had shown limited action to date, despite their stated intentions, due to short-term interests, it said. A transformation to a low-emissions economy was expected to need at least $4tn-6tn a year in investment, the report said, about 2% of global financial assets.

Despite Andersen’s doubts that the necessary emission cuts can be made by 2030, she pointed to the plummeting costs of renewables, the rollout of electric transport, major climate legislation in the US, and moves by pension funds to back low-carbon investments.

“It’s my job to be the ever hopeful person, but [also] to be the realistic optimist,” she said. “[This report] is the mirror that we’re holding up to the world. Obviously, I want to be proven wrong and see countries taking ambitious steps. But so far, that’s not what we’ve seen.”

.gif)