Sakshi Venkatraman

Tue, September 26, 2023

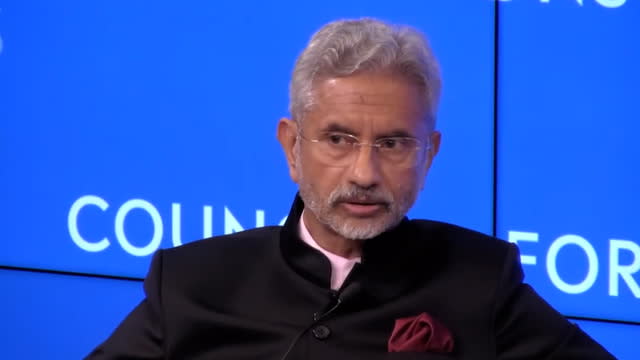

Jason Armond

Indian Americans are now the most populous Asian-alone group in the United States, according to a new report from the Census Bureau.

They have surpassed Chinese Americans, who were previously the largest in that category, though when the populations are counted with multiracial people included, Chinese Americans still make up the largest share of the country’s Asian population at 5.2 million.

Those who identified as “Indian-alone” — that is, as 100% Indian — on the 2020 census numbered nearly 4,400,000. It represents a 55% growth over the course of a decade, and experts say the U.S. is already seeing the impacts.

“It is momentous,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, founder of nonprofit group AAPI Data. “Americans’ perception of who is Asian is still very much informed by demographic patterns from a century ago. They think of East Asians as quintessentially Asian and are less likely to think of South Asians as Asian … Well, the demographic realities have shifted away from the stereotype.”

What is behind the rapid growth

The rapid increase in the population can be traced back to the 1990s, when the tech boom coincided with the start of the H1B visa program for high-skill workers, said Gaurav Khanna, an assistant professor of economics at the University of California at San Diego.

Engineers and computer scientists trained at top schools in India began to immigrate by the thousands with their families, and U.S. tech companies turned their attention to the subcontinent.

“At the time, people were talking about who would be feeding this workforce, and a lot of people thought it was going to be China,” Khanna said. “But in India, people are very comfortable with English … it was a British colony, and that matters quite a bit.”

America has also become a very attractive place for South Asian students on F1 and J1 visas looking to enter high-skill fields, he said. And though there is a burgeoning population of U.S.-born Indian Americans, the vast majority of the population is made of immigrants, according to Census Data.

Among H1B petitioners, Indians make up almost 75%. Chinese nationals, the next largest pool of petitioners, make up only 12%.

“People then go from H1Bs to ultimately applying for and getting green cards, even though there are long delays in those processes,” Ramakrishnan said.

Impacts of the shift

This weight shift in the Asian-alone category is something sociologists say they saw coming for years. And while not as populous as Indian Americans, other South Asian groups are seeing rapid growth as well.

The Nepalese population saw a substantial uptick, the report said, with a 250% overall increase between 2010 and 2020. The Bangladeshi population also grew by 85.4%, due in part to family sponsorships, Ramakrishnan said.

With the 2024 presidential election on the horizon, political experts say it’s a change that is hard to ignore — and one whose impact shouldn’t be underestimated.

“The political parties, when they are looking at Georgia, Virginia, Ohio, Michigan, they need to actually think through, ‘OK, it’s no longer just about Chinese or Koreans. I actually need to have a strategy to actually engage Indian Americans,’” said Christine Chen, executive director of civic organization Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote.

With a largely English-proficient population, reading and submitting ballots don’t pose barriers to the same degree as with other Asian communities, Chen said.

“Not only are they growing in population, but their tendency is to lean in more and participate at a higher rate,” she said.

Political issues important to the diaspora, like discourse around Hindu nationalism and caste oppression, are also making their way into U.S. life, she said. And Indian American figures, like presidential candidates Vivek Ramaswamy and Nikki Haley, are gaining major attention, Khanna said.

“The second generation especially … they’re becoming politically active themselves,” he said.

Ramakrishnan says that, with the recognition of the Census and a new community milestone, both Asian Americans and Americans at large should be paying attention.

“My hope is that this will spark important conversations about the role of South Asians in Asian America,” he said.