"Every time I look out the window, I'm in awe."

By Elizabeth Howell published 2 days ago

Fresh aurora pictures from a NASA astronaut is making us green with envy.

Earlier this month, International Space Station astronaut Jasmin Moghbeli captured absolutely stunning pictures of a flag-like green aurora stretching from the southern regions of the Earth far up into space.

"The auroras from up here are spectacular," NASA's Moghbeli told Space.com during a Wednesday (Feb. 21) ISS press conference about science. Of the green auroras Moghbeli saw on Feb. 15, she said it was one of her space mission highlights witnessing "some green, some red that just swept across the surface of the Earth."

Related: 'Absolutely unreal:' NASA astronaut snaps amazing photo of auroras from space station

The ribbon-like aurora happen on Earth when our sun sends energetic particles towards Earth's upper atmosphere. Our planet's protective magnetic field in turn funnels the particles towards the poles, and the solar particles glow colorfully as they interact with our atmosphere

An aurora visible over Utah from the International Space Station, photographed Oct. 28, 2023 by an Expedition 70 astronaut. (Image credit: NASA)

"I love it," Moghbeli said, "because every time I look out the window, I'm in awe. Every time, it's a little different, even if we're passing over the same part of the Earth. Whether the lights are different, or the clouds or the seasons or the sun angles, every single time I'm amazed at how alive and beautiful our planet is."

If you're looking to snap your own photos of auroras, be sure to check out our guide on how to photograph auroras, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography

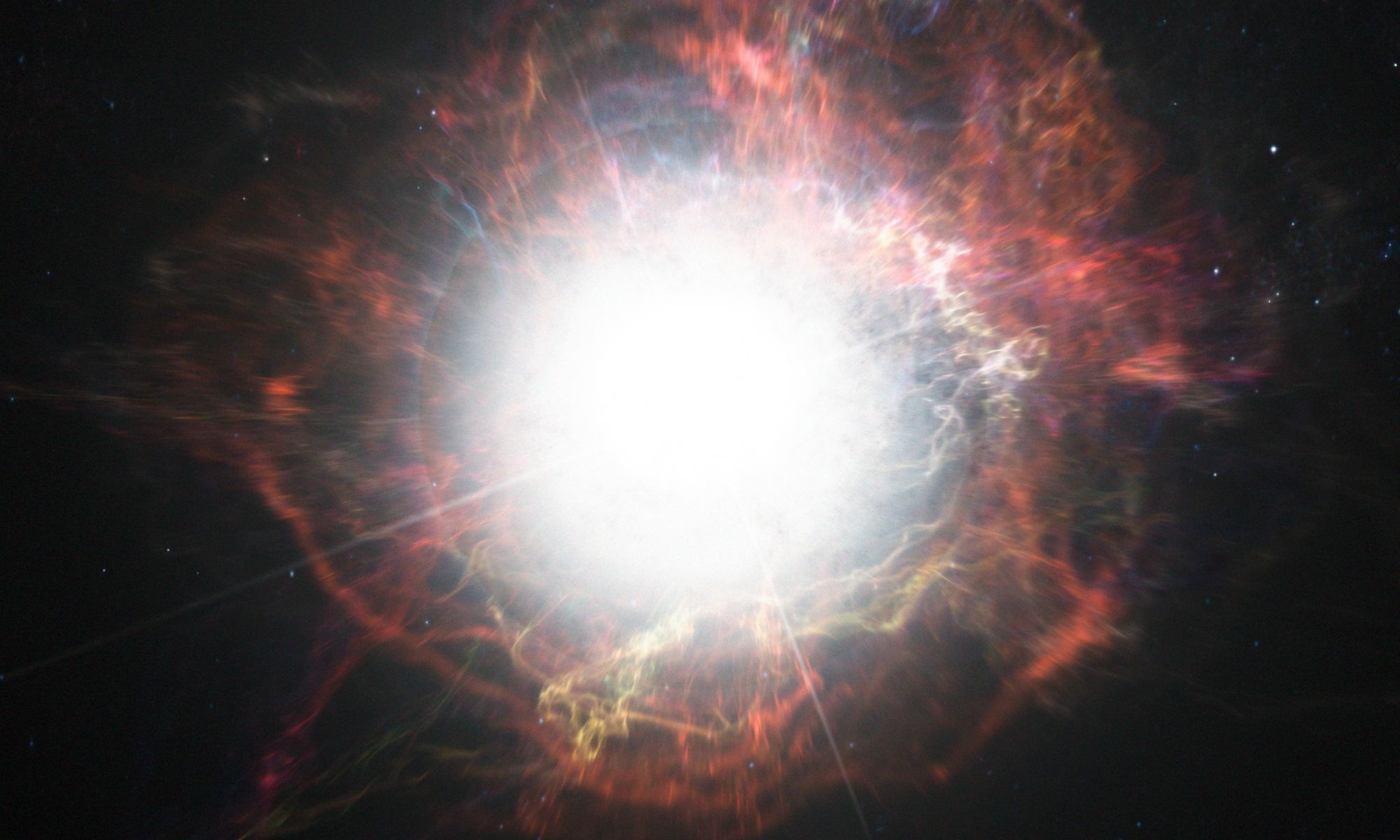

This artist’s impression shows dust forming in the environment around a supernova explosion. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

POSTED ONFEBRUARY 24, 2024 BY BRIAN KOBERLEIN

Life on our planet appeared early in Earth’s history. Surprisingly early, since in its early youth our planet didn’t have much of the chemical ingredients necessary for life to evolve. Since prebiotic chemicals such as sugars and amino acids are known to appear in asteroids and comets, one idea is that Earth was seeded with the building blocks of life by early cometary and asteroid impacts. While this likely played a role, a new study shows that cosmic dust also seeded young Earth, and it may have made all the difference.

Although we’ve long known that cosmic dust accumulated on early Earth, it’s not been seen as a major source for early life because of how it accumulates. With comet and asteroid impacts, a great deal of prebiotic material is present at the site of the impact. Dust, on the other hand, is scattered across Earth’s surface rather than accumulating locally. However, the authors of this new work noted that cosmic dust can accumulate and be concentrated in sedimentary deposits, and wanted to see how that might play a role in the early appearance of terrestrial life

Using estimates of the rate of cosmic dust accumulation in the early period of Earth and computer simulations of how that dust could accumulate in sediment layers over time, the team looked at how concentrated deposits might form. One of the things they noticed was that while cometary impacts could create a local spike in prebiotic material, the amount deposited by cosmic dust was much higher. They also found that the melting and freezing of glacial areas could significantly increase the concentration of chemicals from the dust. For example, for early sub-glacial lakes, the concentration of prebiotic chemistry from dust would have been much higher than that found at impact sites. This means that cosmic dust could have played a much larger role in the appearance of life than impacts.

There is still much we have to learn about early life on Earth and how life can form from prebiotic chemistry, but it is clear that life on Earth is only possible because of extraterrestrial chemistry. From dust came the building blocks of life, and so we and every living thing on Earth can trace its lineage back to the early chemistry of dust in the solar system.

Reference: Walton, Craig R., et al. “Cosmic dust fertilization of glacial prebiotic chemistry on early Earth.” Nature Astronomy (2024): 1-11.

Meanwhile meteorite hunters rushed to Berlin to find this most rare space rock.

A fragment of 2024 BX1. (Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0)

HARD SCIENCE — FEBRUARY 24, 2024

Meg St-Esprit

STORY BY

Earth is being pummeled by meteorites daily, but most of its residents aren’t even aware. According to NASA’s planetary defense system Scout, nearly 50 tons of meteoritic matter hit the planet daily. Most small pieces are never found, but occasionally a celestial fireball pushes through the atmosphere and lands on the ground. And on January 21 outside of Berlin, Germany, that’s just what happened. A meteorite on a wayward journey from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter shattered into dozens of pieces—and meteor hunters from around the world mobilized to begin their search.

In San Francisco, meteor astronomer Peter Jenniskens watched data from Scout as well as the European Space Agency’s Meerkat asteroid guard system, which were tracking the meteorite from Asteroid 2024 Bx1. Jenniskens and colleagues—both professionals and hobbyists—furiously worked to predict where the object would land. Teaming up with Lutz Hecht at the Museum für Naturkunde, he boarded his first of two red eye flights. “I spent my nine hour layover in Newark fruitfully calculating where I expected the meteorites to have fallen,” he says.

Once in Germany, they went directly to the predicted strewn field south of the town of Ribbeck, partnering with more local organizations and hobbyists. “We very quickly had the local science community organized.”

After a search complicated by storms, the team began to recover pieces of 2024 Bx1 on Thursday, February 1. A landscape architect from Poland, Kryspin Kmieciak, found the largest piece—about the size of a baseball. In the meteorite world, he’s known as the “main mass holder.” There’s an entire community of fellow rockhounds, and Kmieciak explains, “I meet a lot of friends when we go search for meteorites.” He plans to open a meteorite shop in Poznań, Poland in the near future.

Meteorite detection has improved over the last few decades, which is why teams were able to quickly locate the strewn field. Robert Lunsford, Fireball Director for both the American Meteor Society and the International Meteor Organization, says astronomers around the globe are constantly watching the skies. “This particular meteor was the size of a very large beach ball,” he says. “When out in space, something this small is very faint, and it was sheer luck that it was found prior to striking the atmosphere.”

NASA located the meteor and gave notification about 90 minutes before impact. That short warning is not concerning, says NASA’s Planetary Defense Officer Lindley Johnson. “If the object were large enough that some damage at the surface of Earth could occur, it would be spotted much earlier than just a few hours away, and the notification process is much more formal to ensure the best available information is provided to our governments and the public.” Astronomers around the world report observations to the International Asteroid Warning Network. This is only the eighth time a small asteroid has been detected while still in space.

One reason it took several days after impact to find meteorite fragments is that this is one of the rarest types of space rock: aubrite. Melinda Hutson, curator of the Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory at Portland State University, says 90% of meteorites are chondrites, which contain metal and are easier to find. Aubrites, though, look like Earth rocks.

To date, there are only fragments of aubrites in 11 collections worldwide. “Some meteorites can give us an idea of how long it took to build the Earth from small pieces. Others give us insights into the formation of the Earth’s core… The types of meteorites give us a picture of what the building blocks of the Earth may have looked like.”

Jenniskens says that while most meteorites have a black or brown fusion crust, these aubrite fragments have a clear crust, like a glass coating, that allows the beauty of each rock to shine through. It’s unique even among already-rare aubrites. He’s not seen anything like it before and hopes to learn more about the origins of life and planetary defense through further study. “What is it going to tell us about the history of Earth and the solar system?” he muses. “And that’s the fun part for us. What information is contained in this little treasure?”

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder.

Artist's illustration of a cold brown dwarf star and IWST

POSTED ON FEBRUARY 24, 2024 BY LAURENCE TOGNETTI

What are the atmospheric compositions of cold brown dwarf stars? This is what a recent study published in The Astronomical Journal hopes to address as an international team of researchers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to investigate the coldest known brown dwarf star, WISE J085510.83?071442.5 (WISE 0855). This study holds the potential to help astronomers better understand the compositions of brown dwarf stars, which are also known as “failed stars” since while they form like other stars, they fail to reach the necessary mass to produce nuclear fusion. So, what was the motivation behind using JWST to examine the coldest known brown dwarf star?

“The coldest brown dwarfs are brightest at infrared wavelengths and extremely faint and difficult to observe at visible wavelengths, so they are very well suited for JWST,” Dr. Kevin Luhman, who is a professor in the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State University and lead author of the study, tells Universe Today. “The target of our paper, WISE 0855, is one of the most appealing targets of any kind for JWST because it is the coldest brown dwarf and is very close to our solar system (the fourth closest system). It is such an obvious object to observe with JWST that it was selected (by multiple teams) for guaranteed time observations with all of the instruments on JWST.”

Dr. Luhman was responsible for discovering WISE 0855, which is located approximately 7.43 light-years from Earth, announcing his findings in a 2014 paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. He concluded that WISE 0855 exhibited a surface temperature of approximately 250 Kelvin (K), henceforth dubbing WISE 0855 as the coldest known brown dwarf star. For context, our Sun’s surface temperature is just under 5800 K, making WISE 0855’s surface temperature less than 5 percent of our Sun. Additionally, Dr. Luhman is responsible for discovering the third closest system, Luhman 16, which is a binary brown dwarf system located approximately 6.5 light-years from Earth.

For this study, the researchers used JWST’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument to examine the atmospheric composition of WISE 0855, to include making new measurements of the surface temperature, which the team concluded is 285 K using several computer models for their calculations. They also attempted to detect phosphine (PH3), which they note has been identified in Y-class brown dwarf stars, along with searching for evidence of water ice clouds based on previous ground-based research. Therefore, what are the most significant results from this study?

The study mentions how better models and unpublished spectroscopy data from JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) could help identify the presence of water ice clouds, with Dr. Luhman telling Universe Today how another team of researchers used NIRSpec in November 2023 to identify spectroscopy variances over time that could contribute to this, as well. As noted, brown dwarf stars are considered “failed stars” since they do not become large enough to produce nuclear fusion like our Sun. Therefore, what is the importance of studying brown dwarf stars?

Dr. Luhman tells Universe Today, “Brown dwarfs are important because they allow us to study the process of star formation in an extreme range of masses (below 10 Jupiter masses), and they allow us to study cool atmospheres that may be similar to those of gas giant planets.”

WISE 0855 does not currently possess any known exoplanets, with exoplanets orbiting brown dwarf stars being incredibly rare finds. One example includes a 2004 study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics identified exoplanet, 2M1207b, orbiting at approximately 55 astronomical units (AU) from its brown dwarf parent star, and is located approximately 170 light-years from Earth. A few years later, a 2008 study published in The Astrophysical Journal identified MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb, which was the first exoplanet discovered orbiting a brown dwarf star at a much smaller distance, only 0.62 astronomical units (AU), and is located approximately 3,000 light-years from Earth. But with so few exoplanets being discovered around brown dwarf stars, what can brown dwarf stars teach us about finding life beyond Earth?

“Brown dwarfs are primarily relevant to studies of gas giant planets, and such planets are unlikely to harbor life since they lack solid surfaces, so brown dwarfs may not tell us much about the prospects of life beyond Earth,” Dr. Luhman tells Universe Today. “But astronomers do speculate about whether life might be possible on planets that orbit brown dwarfs. The main complication of that scenario is that brown dwarfs steadily fade and cool over time, so the temperature of an orbiting planet also would change over time, which might make it difficult for life to survive for billions of years.”

What new discoveries will astronomers make about brown dwarf stars in the coming years and decades? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!

By Joshua Hawkins

Published Feb 24th, 2024

Image: Tryfonov / Adob

A passing star may have altered Earth’s orbit more than three million years ago, researchers have found. A study featured in The Astrophysical Journal Letters suggests that a star known as HD-7977 could have completely changed how our planet orbits the Sun, having lasting repercussions on how Earth developed.

Scientists estimate that HD-7977 flew past our solar system roughly 2.8 million years ago. They believe it may have come within no more than 31,000 astronomical units (AUs) from the Sun, though that number does vary based on who you ask. Further, some believe it could have come as close as 4,000 AU.

The chance that the last bit happened is very small, but if it did, it would be very significant. What’s particularly intriguing about this theory is that stars passing this close to the Sun aren’t really uncommon. A star passes within 50,000 AU of the Sun every 1 million years, scientists estimate. And within 10,000 AU every 10 million years.

But, reverse orbital simulations show that HD-7977’s close encounter with our solar system would have actually been enough to slightly change Earth’s orbit. The idea is based on the fact that any slight variations to the orbit of gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn would lead to orbit changes for Earth, too.

As such, the passing star would only need to perturb Jupiter or Saturn’s orbit for a chance to see those changes reverberate down to Earth, thereby changing our planet’s orbit as well. The exact consequences of this change aren’t clear, but researchers believe there could be evidence of these orbital changes in the planet’s geological record.

The universe is a really big place, and knowing that stars can come within that distance of our solar system and even slightly change our planet’s orbit is scary, especially since any changes to Jupiter’s orbit could have bizarre impacts on Earth.