August 19, 2022

Anyone in journalism who wants to regain that trust would do well to read American Dispatches and internalize the lessons that Robert Parry offers, writes Nat Parry.

Press briefing at the State Department, Feb. 11. (Ron Przysucha/State Department)

By Nat Parry

Special to Consortium News

Americans’ trust in the media has reached all time lows, with just 11 percent expressing confidence in television news and 16 percent expressing confidence in newspapers. These are the startling findings of Gallup’s latest survey of American attitudes about the media, which since 1972 has tracked the ups and downs of public confidence in the news.

An interactive graph at Gallup’s website provides a clear picture of the erosion of public confidence in the so-called Fourth Estate over the past five decades. Peaking in 1979 at 51 percent, the public trust in journalism has been on a steady downward trajectory ever since, with confidence plummeting at key turning points in history. Trust dropped to 35 percent in 1981, the beginning of the Reagan-Bush era and then plunged again to 31 percent in 1987, the year after the Iran-Contra Affair broke.

Since then, public confidence has continued to wane, year after year, with 46 percent of Americans now saying that have “very little” or no trust in newspapers and 53 percent expressing the same distrust of television news. With 37 percent expressing “some” confidence in newspapers and 35 percent having some degree of trust in TV news, the amount of people saying they have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of trust is relatively minuscule.

To make sense of Gallup’s numbers, it is useful to juxtapose them against the media’s coverage of major stories over the decades. When public trust in journalism peaked, at the end of the 1970s, it should be noted that the media had earned a reputation over the previous several years as plucky, independent and adversarial.

Not only had The New York Times published the Pentagon Papers in 1971, which demonstrated that the Johnson administration had systematically lied to the public and Congress about Vietnam, followed by The Washington Post’s expose of the criminal activity of the Nixon White House in the Watergate scandal, but newspapers also regularly published the secrets of the C.I.A. and F.B.I. These included disclosures of the F.B.I.’s COINTELPRO (short for “counter-intelligence program”), which involved the infiltration of American anti-war and civil rights organizations, and a secret assassination program run by the C.I.A. called Family Jewels.

[Related: JOHN KIRIAKOU: J Edgar Hoover’s Evil Brainchild and MLK & Fred Hampton Versus J Edgar Hoover]

New Paradigm

In contrast, by the 1980s, a new paradigm had emerged that was captured well by the title of journalist Mark Hertsgaard’s 1988 book, On Bended Knee: The Press and the Reagan Presidency, which chronicled the relationship between the media and Ronald Reagan. This on-bended-knee obsequiousness had been characterized by a shirking of responsibility on the part of the news media to tell the full story of Reagan’s crimes and misdeeds, including the defining scandal of his presidency, the Iran-Contra Affair.

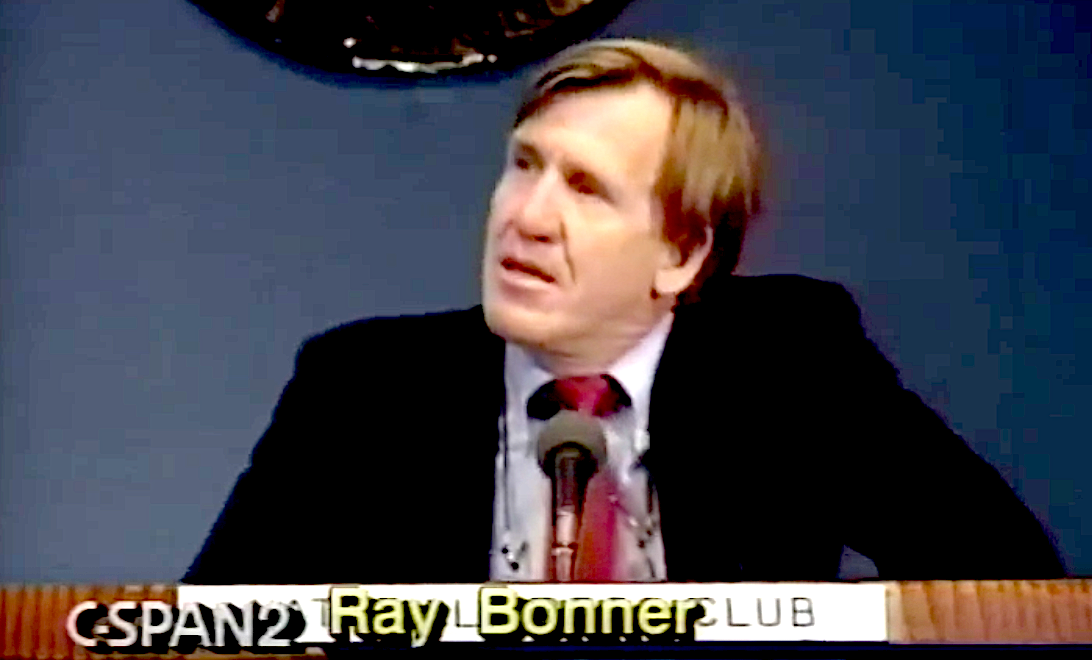

Ray Bonner in a C-Span program on investigative journalism, Jan. 9, 1993. (C-Span)

A seminal moment in this process was the purging of New York Times journalist Raymond Bonner after he reported on the U.S.-backed Salvadoran army’s massacre of men, women and children at a remote village called El Mozote at Christmastime 1981.

The Reagan administration convinced Bonner’s editors that he had been duped by Communist disinformation, while a White House-funded outfit called Accuracy in Media amplified the smears against Bonner and his colleague Alma Guillermoprieto, who were made out to be liars. Under intense pressure and abandoned by his editors, Bonner’s career at The New York Times soon ended.

Although Bonner’s reporting would ultimately be vindicated by a United Nations excavation of the massacre site a decade later, which uncovered hundreds of skeletons — including those of many small children — the failure of The New York Times to back up its reporter who had established the truth in real time enabled the Reagan administration to continue its support for genocidal death squads in Central America.

This failure was partly the result of a systematic effort by the White House, C.I.A. and State Department to contain disclosures and control the media narrative through a strategy called “perception management.”

By applying pressure on editors and TV producers, combined with disseminating misleading information, government officials were able to marginalize honest journalists and present a false picture to the American people about key issues, particularly the dirty wars being fought in their name in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala.

How This Played Out

The full story of how this played out is told in the newly published book American Dispatches: A Robert Parry Reader. Tracing the development of my father Robert Parry’s career in journalism, spanning the Vietnam War era to Russiagate, this collection of his articles sheds light on how the Washington press corps lost its way and how he came to the conclusion that building independent media was essential to save the republic.

As my dad explained in a 1993 speech launching his first book, Fooling America, the press had devolved considerably since the time he arrived in Washington in 1977. It had gone, he said, from “the Watergate press corps,” with all its faults, to “the Reagan-Bush press corps,” which was characterized by cowardice and dishonesty.

In the ‘70s, he explained, the press “was there as the watchdog,” but the press that had emerged by the end of the 1980s was a shell of its former self.

With many of the honest reporters having been purged from the big media outlets, my dad laid the blame squarely with the editors and the news executives who did the purging.

“It wasn’t the White House or the State Department or the embassy in El Salvador that drove Ray Bonner out of The New York Times,” Parry recalled, “it was The New York Times executives who did it.”

Having had his own difficulties with editors and bureau chiefs at The Associated Press and Newsweek who he felt weren’t interested in reporting honestly on the realities of the Reagan-Bush era, by the mid-1990s my dad was also growing increasingly frustrated by what he saw as the timidity and short-sightedness of existing “alternative media.”

When he discovered a treasure trove of documents that put the history of the 1980s in a new and more troubling light, he found that few media outlets — even those on the left — were interested in giving him a platform to report on them. Many of these documents related to the “October Surprise” controversy from Election 1980, namely the allegations that Reagan’s campaign team had colluded with the revolutionary Iranian government to hold 52 American hostages in Tehran until after incumbent President Jimmy Carter had been defeated and Reagan inaugurated.

Although considerable questions remained about this story, most U.S. media outlets had moved on, satisfied that it had been effectively debunked by a congressional investigation. My dad founded Consortium News in 1995, along with a hard-copy newsletter and a bi-monthly sister publication called I.F. Magazine, to enable journalism that could examine tough, controversial stories such as these.

Counter Narratives

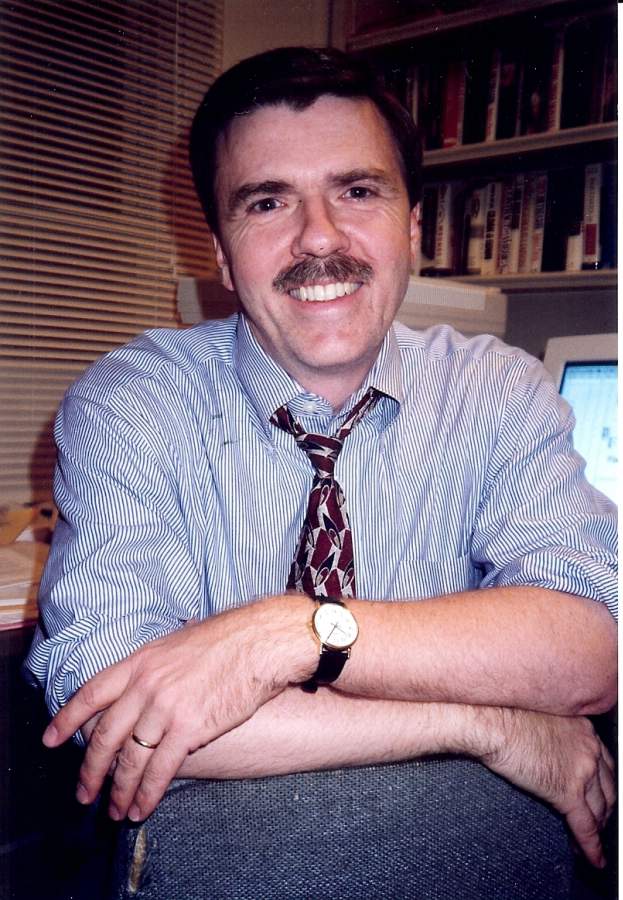

Journalist Robert Parry.

Over the next couple decades, Consortium News would go on to provide honest reporting on a slew of stories that the mainstream media would routinely ignore or get wrong.

My dad’s reporting offered counter-narratives, for example, on the media’s obsession with President Bill Clinton’s sex life, its misreporting on candidate Al Gore’s supposed lies and exaggerations in Campaign 2000 and George W. Bush’s disputed “victory” in which Bush took the presidency despite losing the popular vote and almost certainly losing the key state of Florida had all legally cast ballots been counted.

Other important stories he covered over the years included how the U.S. government looked the other way as drug traffickers imported cocaine into the United States, the politicization of intelligence and abuses of power by the C.I.A., how the U.S. supported an unconstitutional regime change in Ukraine in 2014 and the use of official lies to sell endless military interventions to the American people.

But despite taking pride in the small role he played in developing the new medium of the internet “to allow the old principles of journalism to have a new home,” he acknowledged that Consortium News was “just a tiny pebble in the ocean,” and the undeniable trend was towards a growing clampdown on information.

As my dad would explain in his final article, written on New Year’s Eve in 2017, information was becoming “weaponized” in America, with journalism being used “as just another front in no-holds-barred political warfare.” But the weaponization of information was no longer limited to one political faction or the other. Democrats and liberals, he regretted, had adapted “to the successful techniques pioneered mostly by Republicans and by well-heeled conservatives.”

Even those who came of age during the Cold War and had learned at an early age about the deceptions the government had used to sell the Vietnam War to the American people had come to insist in the Trump era that Americans must “accept whatever the U.S. intelligence community feeds us, even if we’re told to accept the assertions on faith,” my dad wrote.

His goal of building up an infrastructure for independent journalism was to create a home for honest narratives that would counter the mass media’s misrepresentation of history that convinced large segments of the population to buy into a “synthetic reality,” as he called it.

What the steadily eroding trust in the mainstream media reminds us is that even though Americans may be generally misinformed and confused about key topics, there is an instinctive distrust that people feel towards the institutions that are deceiving them.

The latest numbers from Gallup should serve as a wake-up call to the media that it might want to reconsider its approach to journalism. Media executives could look at the high trust that the public placed in newspapers of the 1970s as a clue for what it should be doing today.

Anyone who wants to regain that trust would do well to read American Dispatches and internalize the lessons in journalism that Robert Parry offers.

Nat Parry is a co-author of Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush and is the author of the forthcoming How Christmas Became Christmas: The Pagan and Christian Origins of the Beloved Holiday, being published by McFarland Books.

No comments:

Post a Comment